Picture Twiggy, mid-60s, in a minidress. Her legs spring-loaded with coltish youth, she’s wide-eyed and spidery-lashed. Now picture the classic Dior “new look”: an hourglass jacket whittled to willowy form. A woman stands serene as a ballerina, one pointed toe directed at the camera. Both are fashion photographs selling the world a new silhouette. But both are about so much more than the clothes.

A great fashion photograph is not just about a great outfit. It captures a moment in history. It is more than a portrait of a person; it is a portrait of all of us at that moment. Jumping into the frame like a kid who’s been hiding behind a door, Twiggy is rattling the cage of the establishment with the charm to get away with it.

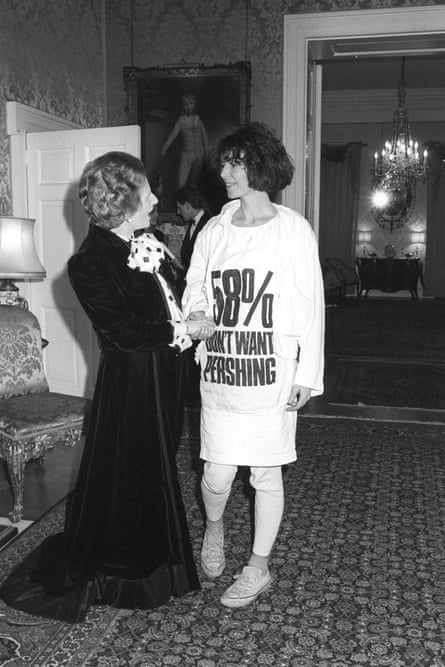

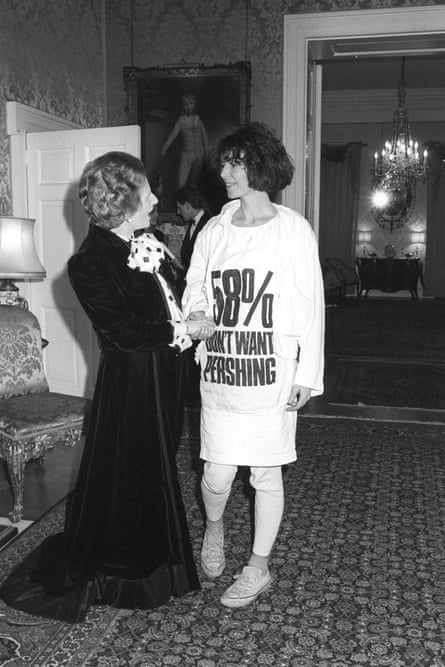

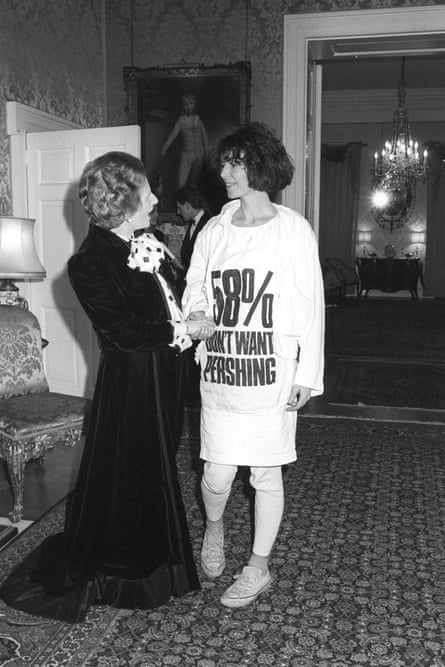

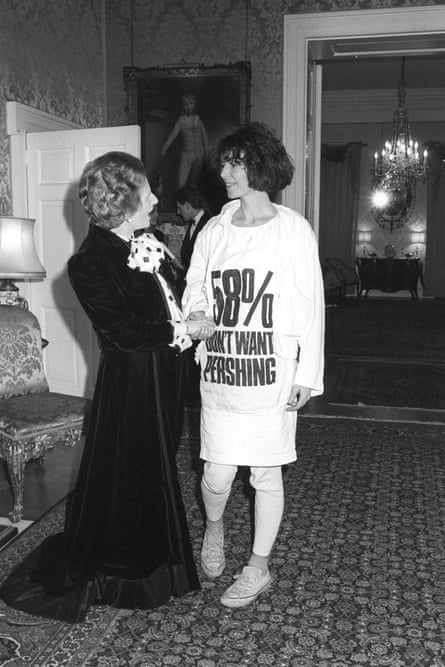

Katharine Hamnett at Downing Street, wearing her “58% DON’T WANT PERSHING” T-shirt – against the proliferation of US nuclear missiles in Europe – is made all the more delicious by the detail that Margaret Thatcher wears a polka-dot pussy-bow blouse, a perfectly matched duel of 80s power dressing. Other times, clothes barely figure. In her first shoot for the Face in July 1990, Kate Moss turned the tables on the ostentatious wealth of the 80s in an instant. She heralded a changing of the guard, and the dawn of the age of grunge.

Polly Devlin, writing in the Vogue Book of Fashion Photography, notes that it is “a unique, valuable and extraordinarily detailed view of women … we see very clearly how women looked; not just how they dressed, but how they desired to look, and were expected to look, and how they were looked at”. The role of women in the workplace, the sexual freedoms won, the political battles fought: all this is played out in front of the camera.

But fashion photography as a picture-book history of women is told mostly from the eye of the beholder. Many images are now shocking for the red flags of abuse the world was oblivious to at that time. Speaking on Desert Island Discs last year, Moss revealed she “cried a lot” on early shoots because she hated removing her clothes, taking Valium to ease her nerves when she had to be topless on set.

The female gaze has begun to shift this power dynamic. Having more women behind the lens in the 21st century has helped make the sexualised tropes of men photographing beautiful women – high-heeled legs, eyes half-closed as if in submissive ecstasy – look dated and tired. More empathy behind the lens has revolutionised the way we think and talk about models. Our definition of beauty has expanded exponentially from the days when it was defined by overwhelmingly white, size six supermodels. Sophie Dahl’s voluptuous figure was a wake-up call to the industry, while Donyale Luna, known as the first Black supermodel, broke boundaries when she graced the cover of British Vogue in 1966. Meanwhile, social media, which transformed the fashion landscape years before it permeated the rest of culture, transformed style’s chain of command.

The best fashion images can stop you in your tracks, a sucker punch of delight, like hearing a great pop song for the first time. But great fashion photography is the exception to the rule. The majority of fashion images are too airless and worshipful to feel alive, too nakedly transactional to make the heart sing. Yet the fact that fashion photographs often have skin in the game of commerce, selling magazines or jeans or perfume, is part of what makes them compelling. Good business is the best art, Andy Warhol said. The story of how our identity as consumers has cannibalised our identity as citizens is a tale of our times, storyboarded with searing clarity on fashion billboards. Guy Bourdin’s unsettling photographs, with women sliced into body parts in the service of selling high-heeled shoes, are both complicit in the weirdness of the world and commenting on it. (See also the meta-commentary of Juergen Teller’s image of Victoria Beckham’s legs spilling out of a shopping bag.)

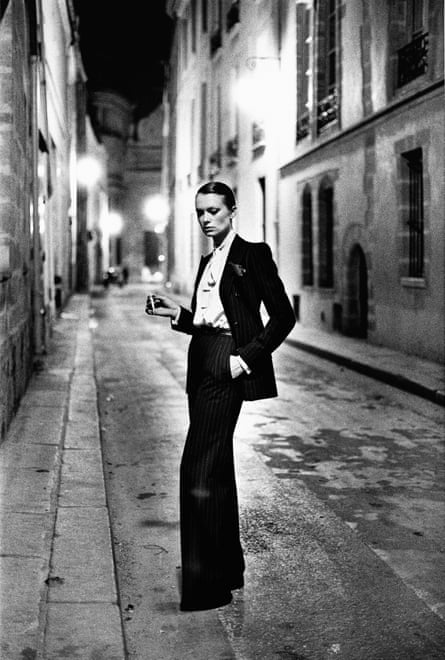

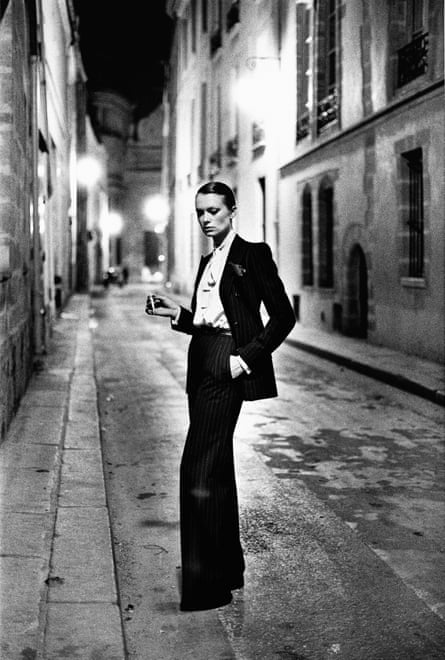

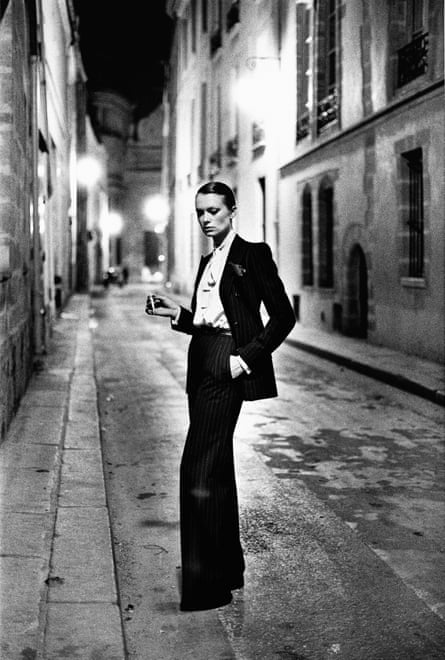

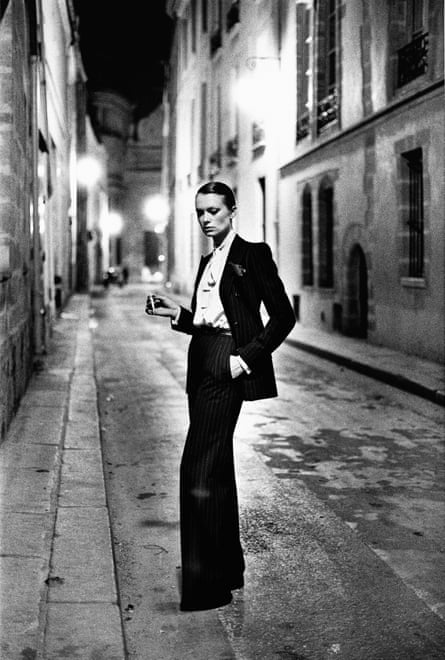

The most memorable fashion photographs have a kind of magic. In 1966, new Parisian fashion sensation Yves Saint Laurent included a woman’s tuxedo trouser suit with a satin side stripe in his couture collection. He called it “Le Smoking”. It was the first time a couturier had presented trousers as women’s eveningwear, and it caused a sensation. Women were turned away from restaurants while wearing it. (When socialite Nan Kempner was refused entry to La Côte Basque in Manhattan, she removed her trousers and wore the blazer as a minidress.) But it was a Helmut Newton photograph, Rue Aubriot, taken nine years later for French Vogue, that became the ultimate iconic image of Le Smoking. The narrow street has a grainy, before-midnight light. The image plays on our expectations of gender in ways that riff on the trouser suit: the model angles her cigarette as if to hide it; the jut of her elbow adds breadth to her shoulders. She doesn’t smile or meet our eye; you can almost see the muscle twitching as she sets her jaw. There are worlds within this image.

What’s more, the photographs on these pages have changed how you and I get dressed. Sometimes this is a new silhouette or proportion, as with the new look or Miu Miu’s micro miniskirt. Sometimes it is a rewriting of etiquette: when Tom Ford unfastened a few extra buttons on a Gucci silk shirt on the Milan catwalk, he may well have unbuttoned yours, too. Sometimes it is a mirror held up to the changes in the world around us. Marc Jacobs’s “grunge” collection stuck a safety pin in a bubble of glamour that hung over fashion from the previous decade. If you ever tied your flannel shirt around your waist or pulled your cardigan sleeves over your knuckles – and didn’t already love Nirvana – well, this is why.

Sometimes, fashion photographs seem to show us a truth they couldn’t possibly have grasped at the time. The spectacle of Shalom Harlow being spray-painted in a white dress on the Alexander McQueen catwalk is even more unsettling to watch now, in the year of AI, than it was then, capturing a sense of power and agency shifting from humans to robots before our eyes. That McQueen show took place in 1998. Fashion often looks like nothing more than fantasy. But – as these photos show – it might just speak the truth. JCM

Christian Dior’s New Look

By Willy Maywald, 1947

Days after Christian Dior showed his 1947 New Look collection in Paris, with its voluminous skirts, beading and silk, salesgirls tore apart his dresses and protesters took to the streets with signs that read, “Burn Dior!” Having embraced the wartime mantra of “make do and mend”, many women were shocked by the collection’s embrace of excess. Others were angered by the cinched waists and longer length skirts, having enjoyed greater freedom in their utilitarian uniforms. Fearing the collection would lead to demand for more fabric, the Board of Trade banned British Vogue from mentioning Dior in its pages. Describing the look as “the quintessence of femininity”, the curator and fashion historian Pamela Golbin says, “Fashion has always been a mirror of societal needs and desires. In the postwar period, the New Look put an end to functional clothing and signalled the beginning of the golden age of couture.”

Twiggy wearing Mary Quant

By Popperfoto, 1966

Mary Quant’s above-the-knee hemlines defined the fashion of London’s swinging 60s, and the British model Twiggy captured the new attitude. Gone were long, heavy skirts and uncomfortable girdles. In their place arrived miniskirts with pockets, worn with tights, not stockings. In her 1966 autobiography, Quant, who died in April, described fashion as “a tool to compete in life outside the home”.

A Leigh Bowery look

By Fergus Greer, 1989

The late Australian performance artist Leigh Bowery had a profound influence on many designers. Provocative, and at times perversive (he once sprayed enema fluid over unsuspecting audience members), Bowery embraced the theatrical, strutting around London’s Soho in towering heels, gimp masks and clothing with cartoon-like proportions. In 2016, designer Rick Owens channelled Bowery’s “Birthing Performance” by strapping gymnasts to model’s bodies, while Martin Margiela paid homage to his bulbous tulle headdress in 2009.

Guy Bourdin’s surrealism

By Guy Bourdin, 1979

The 20th-century French artist Guy Bourdin pushed the boundaries of fashion photography, using images to challenge the viewer to imagine a story, rather than just focusing on a product. The surrealist influence in his pictures is often credited to his early work with the American visual artist Man Ray. During the 60s and 70s he turned ordinary locations such as an alleyway, a bedroom and a car into melodramatic, often sinister sets, exploring themes of sexual violence and sadomasochism. This photograph was taken for a spring campaign for the French label Charles Jourdan.

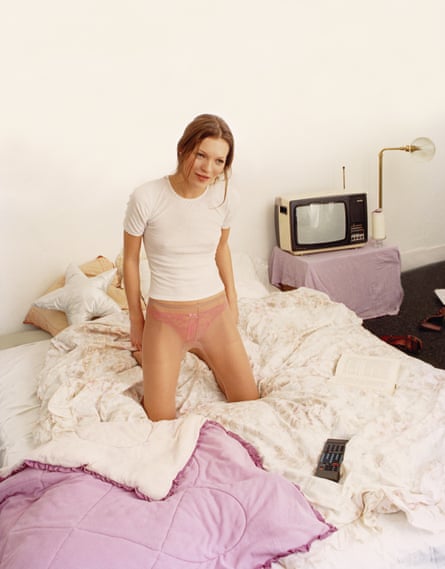

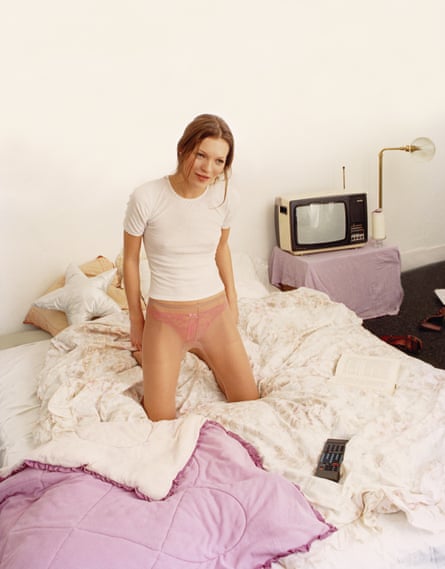

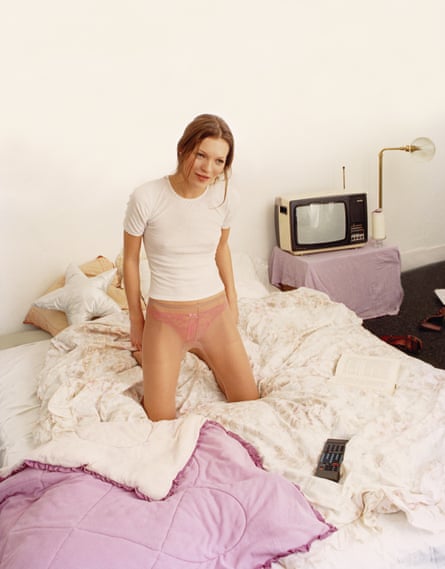

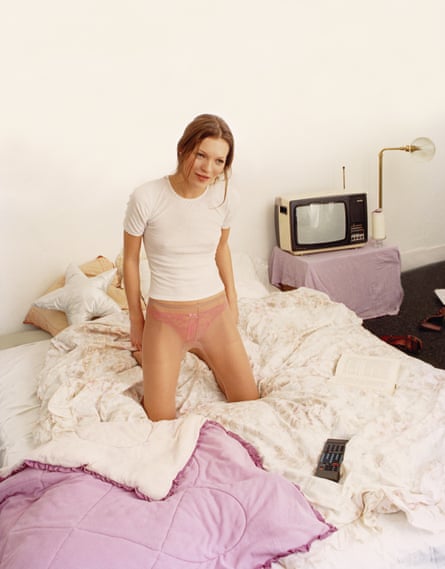

Teenage Kate Moss

By Corinne Day, 1993

A series of images taken by Corinne Day of the teenage Kate Moss helped define the 90s, capturing a hedonistic early stage of Cool Britannia. Day’s grungy aesthetic and Moss’s body shape sparked debates around “heroin chic”. Moss later admitted Day could be “tricky” to work with: “She would say, ‘If you don’t take your top off, I’m not going to book you for Elle.’ It is painful. I loved her, she was my best friend, but she was a tricky person. The pictures are amazing, so she got what she wanted and I suffered for them, but they did me a world of good really. They changed my career.”

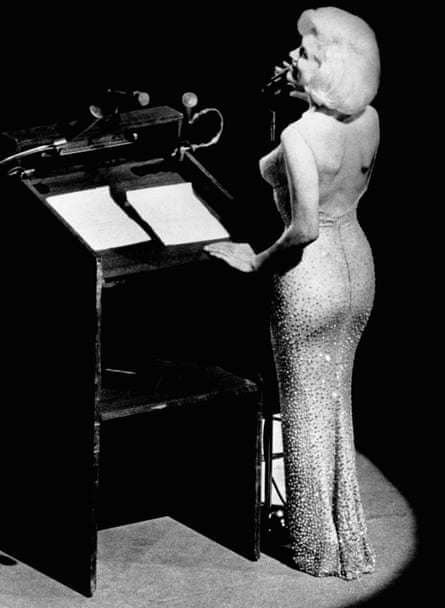

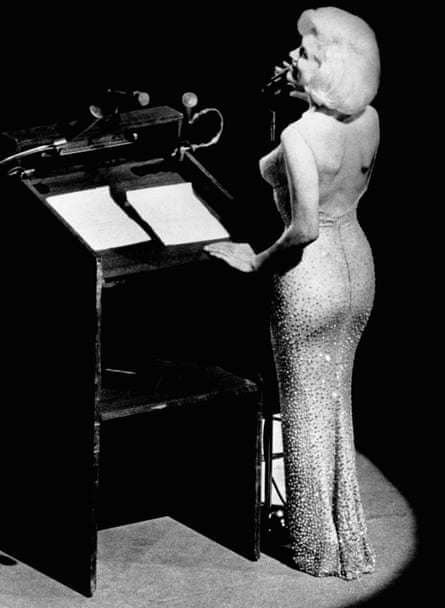

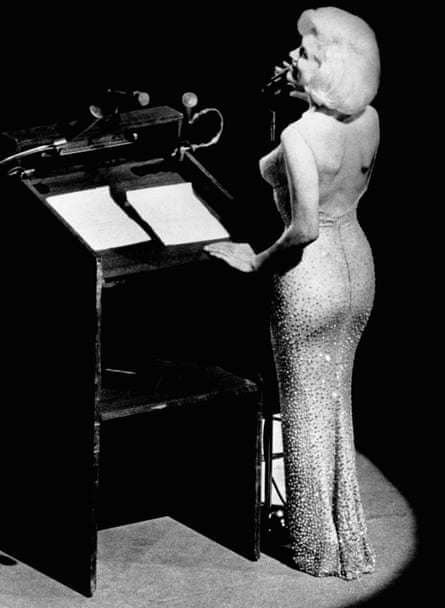

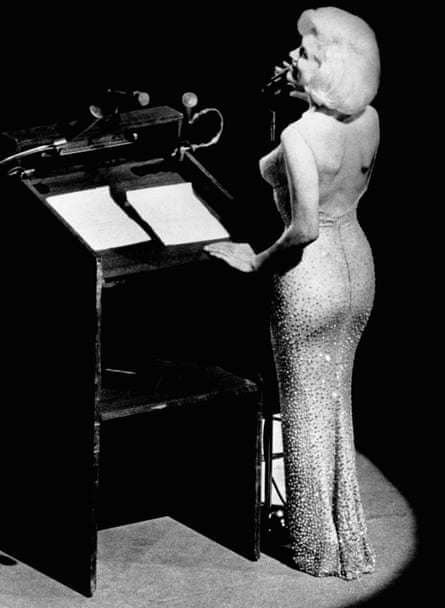

Marilyn Monroe’s JFK dress

By Bettmann Archive, 1962

On 19 May 1962, Marilyn Monroe tottered across the stage at New York’s Madison Square Garden to sing Happy Birthday to President John F Kennedy. The audience gasped as she slowly shrugged off a white fur coat to reveal a skin-tight slinky dress, sketched by young designer Bob Mackie, in the same colour as her skin tone and covered in more than 2,500 crystals. Fast forward to May 2022 and the dress made headlines again when Kim Kardashian wore it to the Met Gala. Mackie described the loan as “a big mistake”, saying Monroe’s dress “was designed for her, and no one else should be seen in that dress”.

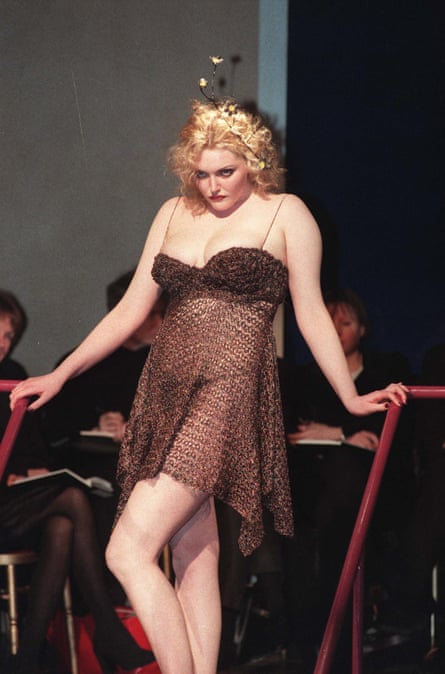

Sophie Dahl on the runway

By Richard Chambury, 1997

After magazine editor Isabella Blow spotted her crying on the street, Sophie Dahl soon became one of the world’s most famous plus size models. At a time when “heroin chic” ruled the runway, the press tormented the granddaughter of Roald Dahl about her curvier body. “At first I found it baffling,” Dahl told an interviewer in 2008. “At 18 you do not set out with any great agenda … In retrospect I see why the whole thing happened.”

André Leon Talley’s Uggs

By Ugg, 2021

Once seen as “ugly footwear”, today you’re more likely to spot Ugg boots on the front row at fashion week than you are a pair of killer high heels. Nothing better encapsulated the shift to sensible shoes than when, in 2021, the late André Leon Talley – a revered editor at US Vogue who died in 2022 – fronted a campaign for Ugg. Declaring them “comfort food for my feet”, Leon Talley said he had collected “dozens” of pairs.

Billy Porter’s Met Gala entrance

By Matt Winkelmeyer, 2019

For the 2019 Met Gala, themed around Susan Sontag’s essay Notes on “Camp”, actor Billy Porter nodded to Cleopatra and ancient Egypt. He was carried up the steps of New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art by six shirtless men, wearing a crystalised jumpsuit featuring 10ft wings and a 24-carat gold headpiece. It was, said David Blond, co-founder of designers The Blonds, “like wearing a weighted blanket”. His team worked for over three months to create the complete look. Porter, whose red carpet style regularly confronts gender norms, told Vogue, “Camp is often used as a pejorative. When it’s done properly, it’s one of the highest forms of fashion and art.”

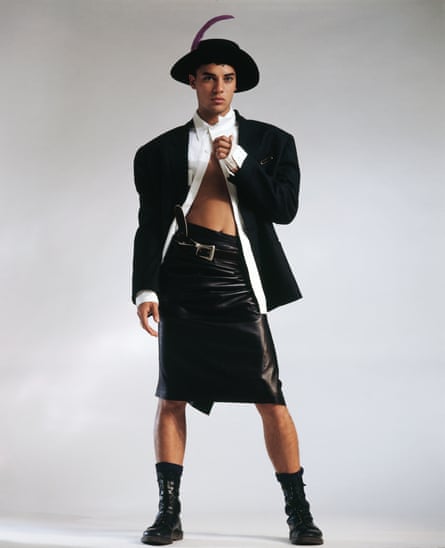

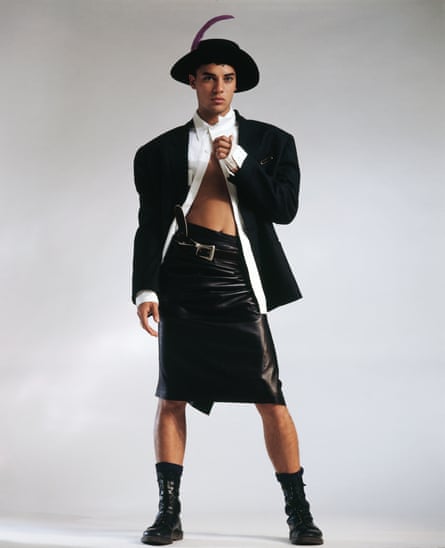

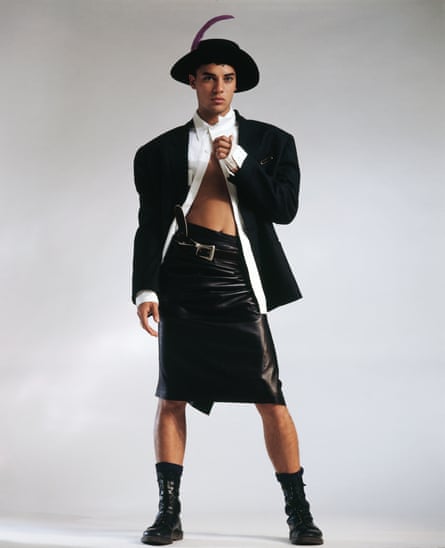

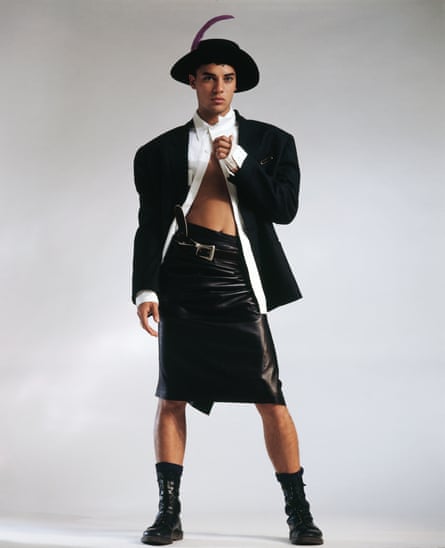

Nick Kamen in a skirt

By Jamie Morgan, 1986

More than 30 years after his death, designer Ray Petri’s influence continues to pervade fashion. Men in skirts, and sports gear as luxury fashion pieces, were all looks championed in the 80s by Petri, who was joined by a small group of close confidants in London working under the moniker “Buffalo”. The group soon shaped the decade’s approach to menswear. Their name alludes to Bob Marley’s Buffalo Soldier, and Neneh Cherry made the sobriquet mainstream with her 1988 hit Buffalo Stance. The photographer Jamie Morgan captured much of Petri’s daring aesthetic. Forerunners such as The Face championed them, but Petri died before the true impact of his work became apparent.

Lady Gaga’s meat dress

By Matt Sayles, 2010

Created by the artist and designer Franc Fernandez, Lady Gaga’s viral “Meat Dress”, worn at the 2010 MTV VMAs, featured 50lb of rib and steak, purchased from Fernandez’s local butcher, sewn on to a corset and turned into a fascinator. It acted as a precursor to Gaga’s “The Prime Rib of America” speech, where she lobbied against the US military’s Don’t Ask Don’t Tell policy for LGBTQ+ personnel, and it ushered in a new era of stunt dressing for the viral age.

Vogue Italia’s Makeover Madness

By Steven Meisel, 2005

As one of the fashion industry’s pre-eminent photographers, Steven Meisel’s career spans countless shoots for Vogue and campaigns for Calvin Klein, Versace and Prada. The American’s style is diverse: at times it’s unpretentious in black and white; at other times, complex and colourful. A prolific worker, Meisel has pushed the boundaries of fashion imagery, regularly using it as tool for social commentary, such as this image from a shoot for Vogue Italia, “Makeover Madness”, which looked at how cosmetic surgery had become as intrinsic to modern body image as fashion itself.

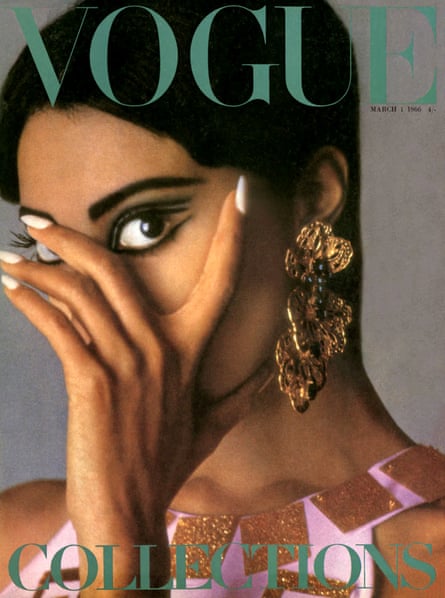

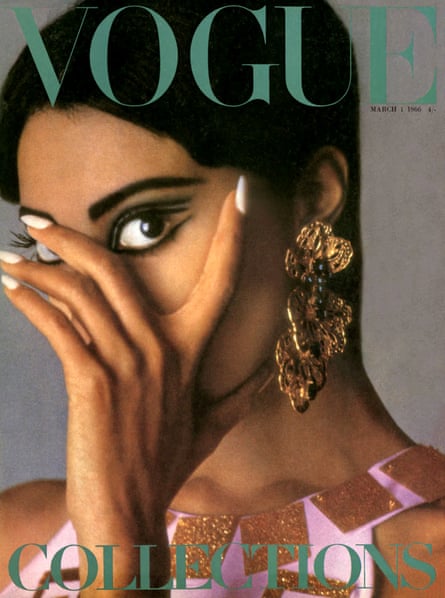

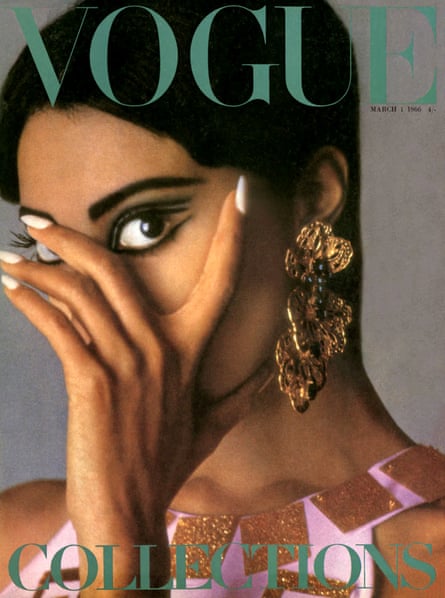

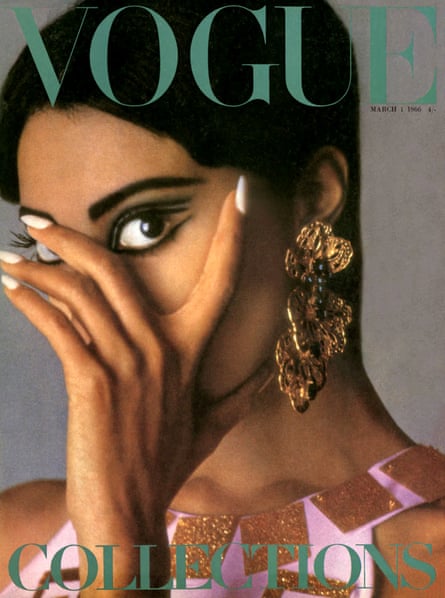

Donyale Luna’s British Vogue cover

By David Bailey, 1966

In March 1966, Donyale Luna became the first Black model to appear on the cover of British Vogue. Shot by David Bailey and inspired by Picasso’s disjointed portraits, Luna holds the gaze of the viewer through one eye, peeking through fingers forming a V for Vogue. Luna’s appearance on the mainstream magazine was of huge cultural significance. She paved the way for other Black models, including Beverly Johnson who in 1974 became the first Black cover star for US Vogue.

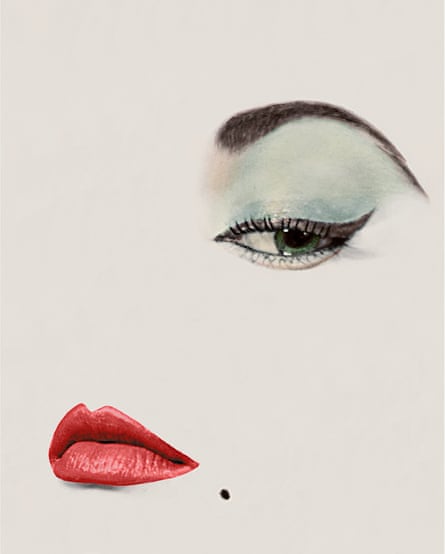

Doe Eye

By Erwin Blumenfeld, 1950

Dubbed a visual haiku, the American photographer’s sparse cover for Vogue broke the fashion mould. The model Jean Patchett was reduced to four features: arched brow, heavily lined left eye, crimson lips and mole. It turned her into the face of a decade, as consumers experimented with the “doe eye” look, later emulated by Edie Sedgwick in the 60s.

Virgil Abloh takes a trip to Oz

By Frédérique Dumoulin, 2018

In March 2018, the late Virgil Abloh made history when he was appointed artistic director of Louis Vuitton menswear, becoming the first Black person to hold the position. Hailed as a fashion maverick (he was also a DJ, furniture designer and artist), he redefined luxury, marrying it with the worlds of hip-hop and hype culture. His debut collection for the luxury French house was inspired by the 1939 musical film The Wizard of Oz. Fashion students sat on the front row while models from every continent in the world (bar Antarctica) walked down a gradient rainbow runway – referencing Abloh’s own extraordinary journey along the Yellow Brick Road.

The 1950s woman

By Louise Dahl-Wolfe, 1953

When Harper’s Bazaar editor Carmel Snow wanted to portray a more modern, liberated woman, she turned to Louise Dahl-Wolfe. Shunning the studio and heading outdoors to capture both models and clothes in motion, her work broke ground, and helped forge the way for other female photographers. “She was the bar we all measured ourselves against,” Richard Avedon later said. Pictured here is American model Jean Patchett in Granada.

Victoria Beckham in a bag

By Juergen Teller, 2008

Back in 2008, Victoria Beckham was known best for her permatan and ability to never smile in photographs. So it surprised everyone when she agreed to appear in a tongue-in-cheek ad campaign for Marc Jacobs. Shot by the provocative German photographer Juergen Teller, Beckham was captured with her bare legs and high-heeled feet (tan marks and all) flopping over the side of an embossed shopping bag. Recalling the shoot, Teller said, “I told her, ‘You’re the most photographed woman in the world. And fashion nowadays is all about product … bags and shoes … and you’re kind of a product yourself, aren’t you?’ She was, like, ‘Uh, yeah.’” A decade later, Beckham, now herself a respected designer, recreated the image with Jacobs’s blessing for the 10th anniversary of her own fashion line.

Jerry Hall in the USSR

By Norman Parkinson, 1975

When a team from British Vogue – including photographer Norman Parkinson, stylist Grace Coddington and model Jerry Hall – were asked to shoot in the Soviet Union, they became the first fashion magazine to receive such an invitation. Appointed a tourist guide, they travelled around with Parkinson pushing Hall, then 18, to the extreme. She climbed up oil rigs, stood on a specially commissioned plinth in the Red Sea and fell off a horse riding bareback.

Andy Warhol and members of The Factory

By Richard Avedon, 1969

Andy Warhol’s studio space, dubbed The Factory, attracted an avant garde coterie of artists, film-makers and aspiring superstars. In 1969, Avedon, the celebrated fashion photographer who contributed to Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, capturing everyone from pop stars to political activists, turned his attention to Warhol. He invited the artist and his inner circle to be photographed at his own studio. The resulting images – featuring the film director Paul Morrissey, the poet Gerard Malanga and the actor and “Warhol superstar” Candy Darling, with penis (which she referred to as her “flaw”) on display – were regarded as highly transgressive at the time.

Yves Saint Laurent’s Le Smoking

By Helmut Newton, 1975

In 1966, Yves Saint Laurent unveiled “Le Smoking”, the first time any designer had suggested women’s suits for eveningwear. Inspired by the silk-lapelled jackets men wore to protect their clothing from cigar ash, YSL’s womenswear version came with a gently tapered waist and sleeker collar. “I was deeply struck by a photograph of Marlene Dietrich wearing men’s clothes,” the designer said. “A tuxedo, a blazer or a naval officer’s uniform – a woman dressed as a man must be at the height of femininity to fight against a costume that isn’t hers.” It was initially snubbed by his couture clients who deemed it too radical. But months later he included a similar piece in his more affordable ready-to-wear line, Rive Gauche, and it became an instant hit.

Jennifer Lopez’s Versace dress

By Vittorio Zunino Celotto, 2019

Without Jennifer Lopez’s jungle-printed Versace dress, the internet would have been a very different place. After the singer and actor wore it on the 2000 Grammy awards red carpet, the tech team at Google noticed it was the most popular search query ever. At the time, search results were just a list of blue links. Weeks later Google Image Search was soon born. At a 2019 Versace show, J-Lo broke the internet again when she wore a take on the original dress.

Jean Shrimpton’s 60s street style

By David Bailey, 1962

Clutching an old teddy bear and posing against the gritty streetscapes of New York City, Jean Shrimpton’s 1962 shoot with David Bailey for Vogue broke all the rules and, in doing so, established the duo as central figures of the 60s cultural revolution. Until then, magazine shoots usually took place in a studio, with aristocratic models in classic poses. Shrimpton, a “home counties girl”, and Bailey, from London’s East End, rebelled by shunning hair and makeup, and embracing a raw street reportage aesthetic.

Katharine Hamnett’s slogan tee

By PA, 1984

In 1984, British designer Katharine Hamnett made headlines by shaking hands with the then prime minister Margaret Thatcher wearing a T-shirt that referenced the stationing of US nuclear missiles across western Europe. Hamnett said Thatcher “let out a squawk, like a chicken” when she bent down and read it. Now 76, Hamnett continues to produce slogan tees, including most recently “Cancel Brexit” and “Don’t Shoot”.

Devon Aoki and digital deception

By Nick Knight, 1997

Years before Instagram filters and AI had entered the cultural lexicon, photographer Nick Knight was exploring digital deception. This shoot with Devon Aoki pushed the boundaries of conventional fashion photography and still sparks conversation today. Wearing a floral Alexander McQueen dress, Aoki appears as half-human, half-monster, her left eye glowing blue, her forehead spliced open, revealing pink cherry blossom blood.

Fendi’s China show

By Fendi, 2007

When Fendi transformed a section of the Great Wall of China into a sloping runway, 500 guests sat on heated benches, sipping hot chocolate as 88 models – eight being a lucky number in China – showcased its spring/summer 2008 collection. By doing so, Fendi signalled they were serious about catering to the rapidly growing appetite for luxury in east Asia. Since then, the market continues to expand, with international buyers flocking to Seoul fashion week while brands vie over K-pop stars to front campaigns.

Schiaparelli’s shoe hat

By Ullstein Bild, 1937

Designed to both shock and amuse, 20th-century Italian fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli’s collaborations with Salvador Dalí continue to be referenced by designers today. The shoe hat, made in 1937-38, evolved from a photograph Dali’s wife Gala had taken of him wearing one of her slippers on his head.

Alexander McQueen’s robots

By Ken Towner, 1998

Alexander McQueen’s “No.13” show took place at an unused bus depot in London’s Victoria. Celebrities were shunned; McQueen reportedly didn’t want them to detract from the clothes. Instead the installation team were invited to bring along friends as thanks for putting up the stadium seating for free. The finale, inspired by artist Rebecca Horn’s installation of two shotguns firing blood-red paint at each other, saw model Shalom Harlow stand on a revolving wooden turntable as two mechanical robots began to spray paint at her. “And when they were finished,” Harlow later recalled, “they sort of receded and I almost staggered up to the audience and splayed myself in front of them with complete abandon.”

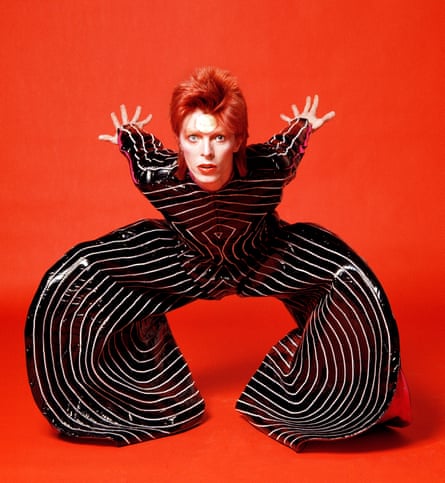

David Bowie wearing Yamamoto

By Masayoshi Sukita, 1973

David Bowie was the master of reinvention. Some of his most memorable looks – including this famous Ziggy-era jumpsuit – were thanks to a longstanding partnership with the designer Kansai Yamamoto, whose avant garde designs often incorporated elements from Japanese culture. Bowie wore pieces from both Yamamoto’s menswear and womenswear collections, later becoming a reference for modern gender-defying fashion. Speaking about Bowie in 2016, Yamamoto said, “Some sort of chemical reaction took place. My clothes became part of David, his songs and his music. They became part of the message he delivered to the world.”

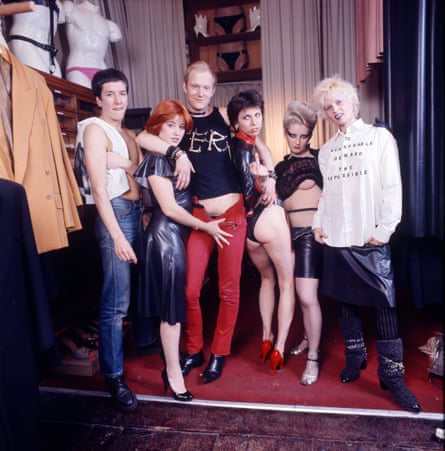

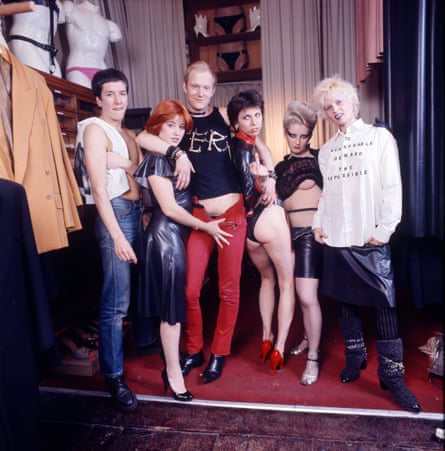

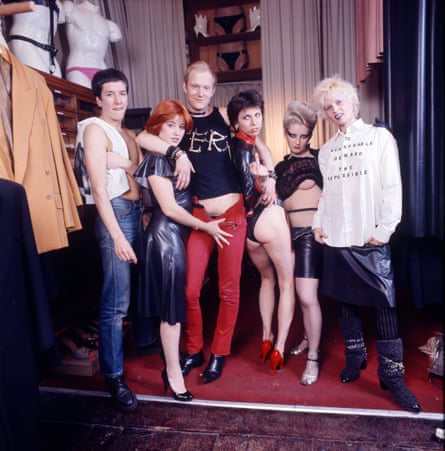

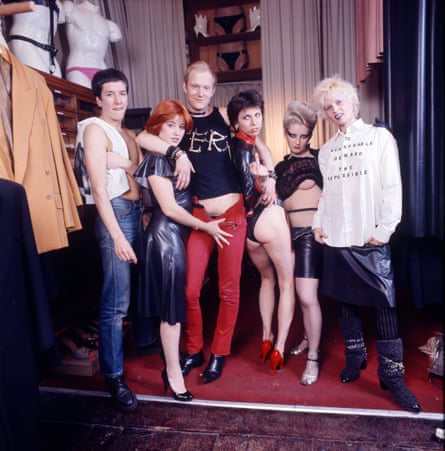

Vivienne Westwood’s Sex shop

By David Dagley, 1976

Vivienne Westwood (on right) and then partner Malcolm McLaren’s shop Sex – later renamed Worlds End – on London’s Kings Road featured phallic graffiti and feminist tracts on the walls, and sold whips and chains as well as rubber skirts and T-shirts with pornographic text. Sales assistants included Chrissie Hynde (centre) and the Sex Pistols’ Glen Matlock (fellow Pistol Steve Jones is on the left), while sex workers and Sloane Rangers shopped side by side. Speaking about the portrait, Sex employee Pamela Rooke, AKA Jordan, said, “I’m not sure why I lifted my top, but it felt right, and still does. There’s nothing sexual about it. It’s empowering: a young woman who is comfortable in her own skin. After, I went back to serving customers. It was all fairly matter-of-fact.” The shop was integral to the punk scene, inspiring the aesthetics of Adam Ant and Siouxsie Sioux, and served as a meeting point for Sid Vicious, Hynde and John Lydon.

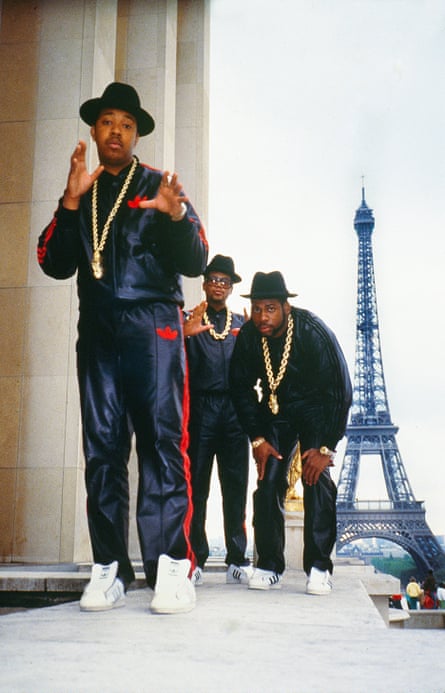

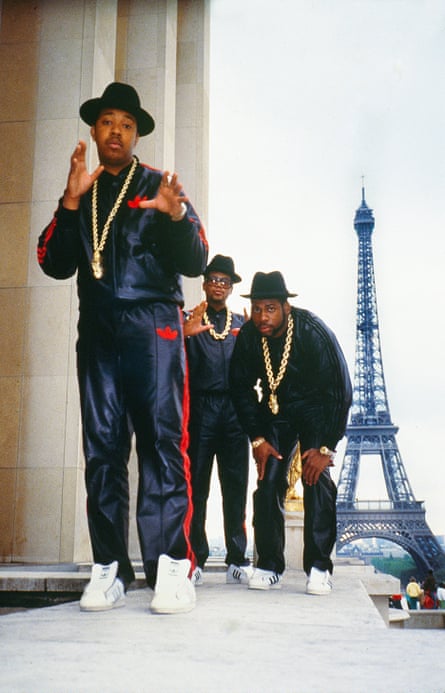

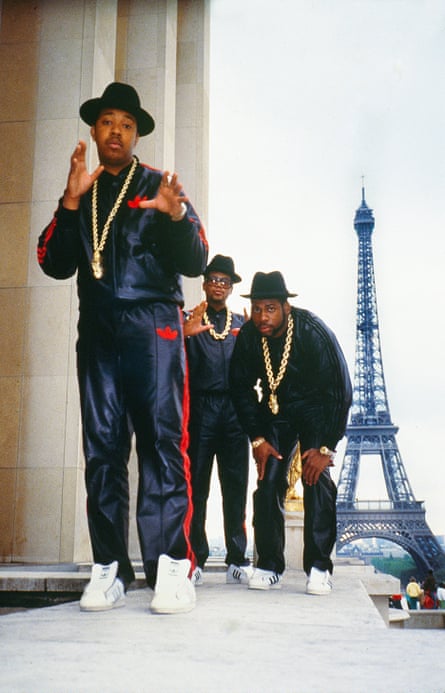

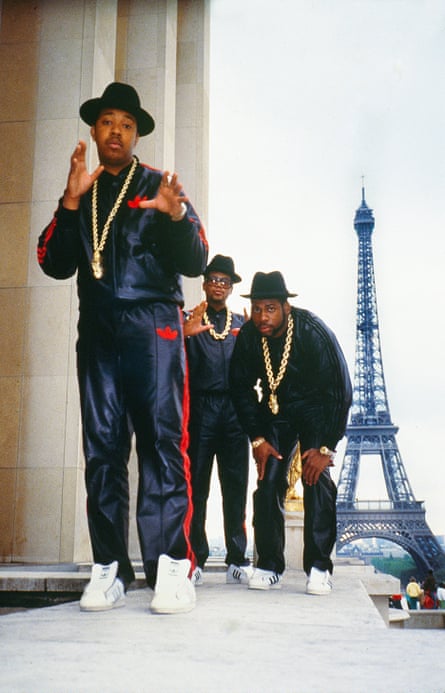

Run-DMC’s Adidas tracksuits

By Ricky Powell, 1987

“What was revolutionary about Run-DMC’s style was that they were not dressing up. They were wearing what kids wore on the street, things like Kangol hats, Adidas sneakers and tracksuits,” says Shad Kabango, rapper and presenter of the Netflix documentary series Hip-Hop Evolution. “They gave hip-hop its own style. Their early records were so different from even the disco-oriented rap of Kurtis Blow or Sugarhill Gang. It was more raw and street. It made sense for their clothing to match that.”

Their 1986 single My Adidas was recorded without the brand’s consent and revolutionised the relationship between fashion and music. The turning point came when an Adidas employee told his bosses he had witnessed tens of thousands of fans lifting their Adidas sneakers into the air at a gig. Weeks later Run-DMC became the first hip-hop group to receive a million-dollar endorsement deal.

Miu Miu’s micro mini

By Estrop, 2021

Miu Miu declared the end of pandemic sweatpants when it sent a micro mini down its 2022 spring/summer runwayr. Both low rise and bottom skimming, it featured a raw-edged hem and exposed pockets, giving the impression of a teenager who had hacked their school skirt with kitchen scissors. The world went mad for it. The shopping site Lyst was getting 900 searches a day, while TikTok was peppered with videos on how to create your own. When the then 54-year-old actor Nicole Kidman wore it on the cover of Vanity Fair, a fight over age-appropriate dressing erupted online, with Kidman later defending the styling, saying she “begged” to wear the outfit. Meanwhile when plus-sized model Paloma Elsesser wore it on the cover of i-D, there was fury that a skirt had to be custom made to fit her.

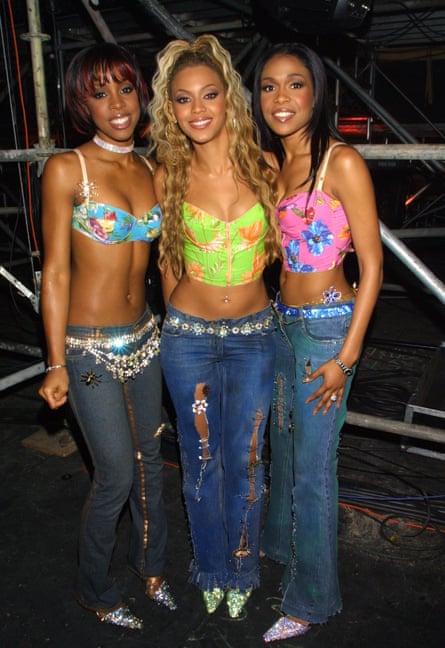

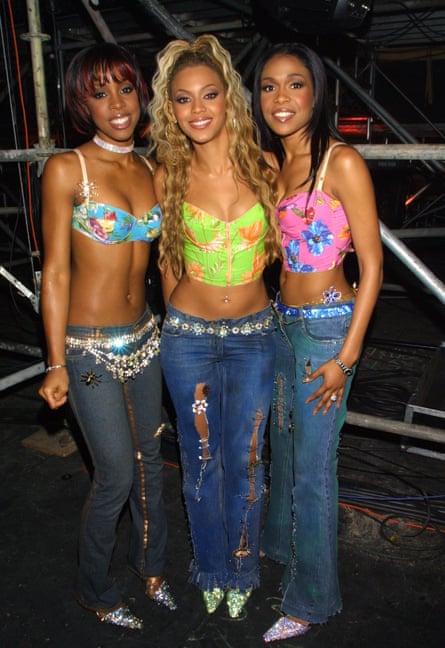

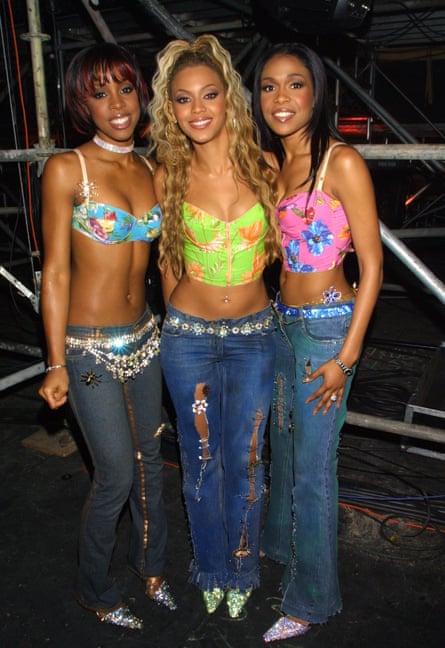

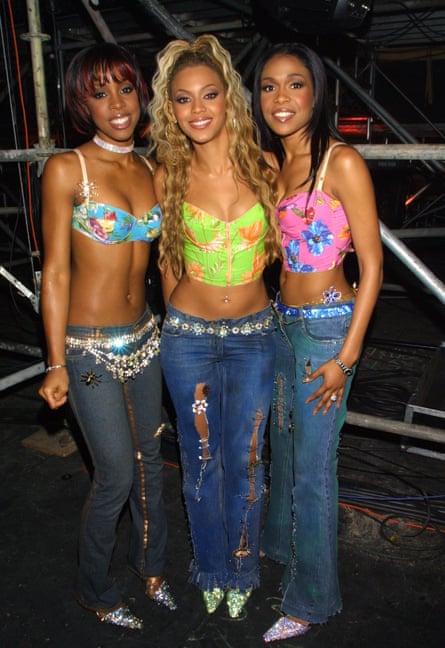

Destiny’s Child’s Y2K style

By Kevin Mazur, 2001

Jeans and a nice top? Destiny’s Child defined the style of the late 90s and early 00s, popularising key aspects of Y2K style – low-rise jeans, sparkly chain belts, bustier tops – that TikTokers would emulate two decades later. Tina Knowles-Lawson, Beyoncé’s mother, served as their stylist, later revealing that many designers wouldn’t dress the trio so she made pieces herself <>. Speaking to W magazine in 2020, Knowles-Lawson said that she was advised by the group’s label to tone down their outfits. “I took offence to it because I felt like the girls, in their splendour, were different, they were unique, they were unapologetically Black.”

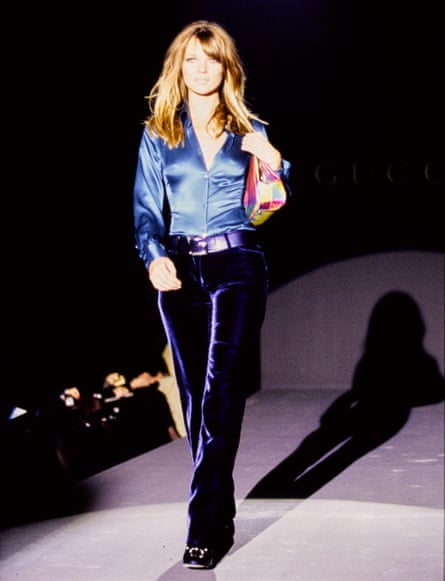

Tom Ford’s Gucci collection

By Guy Marineau, 1995

American designer Ford joined Gucci in 1990 and is widely credited with saving the Italian brand from bankruptcy, transforming it into a coveted symbol of sex and glamour. His 1995 collection featuring velvet suiting and satin shirts, modelled by Kate Moss and Amber Valletta, was an instant hit – revenues doubled over the next nine months, Ford was hailed as a major talent and Madonna would chant “Gucci, Gucci, Gucci” when dressed in the collection at the MTV VMAs. Ford was contractually forbidden to take a bow, but ignored the clause, telling Dazed, “The next day you could not get into the showroom. It was absolute hysteria. So, no, no one gave me flak after that.”

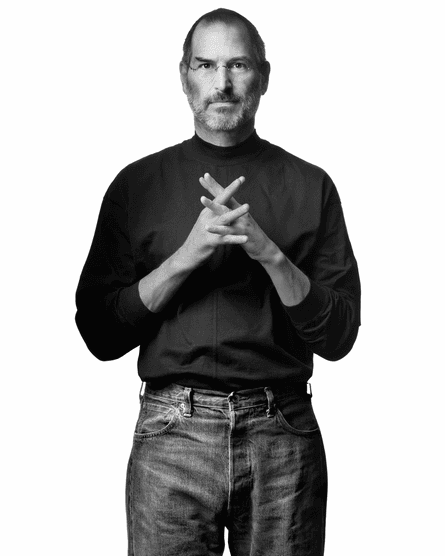

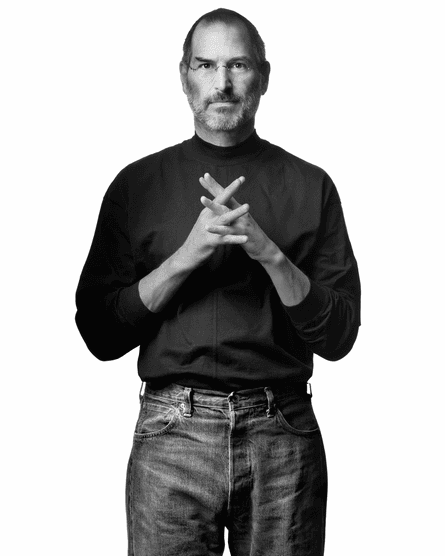

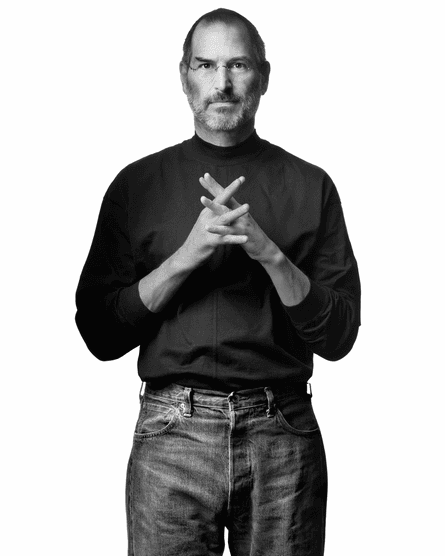

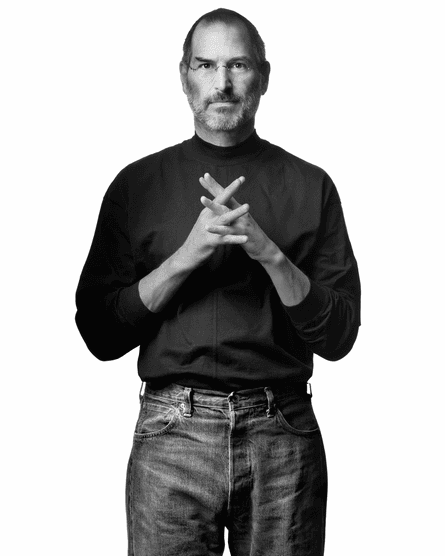

Steve Jobs’s uniform

By Albert Watson, 2006

Steve Jobs took a simple approach to dressing: the Apple co-founder was said to have owned more than 100 black roll-neck jumpers, made for him by his friend Issey Miyake. Levi’s 501 jeans worn with New Balance trainers or Birkenstocks formed the rest of his uniform. From the mid-90s to his death in 2011, it was rare to find him pictured in anything else. Supposedly pegged to the idea of “decision fatigue” – ie, the time taken to choose what to wear would use up valuable brain space – tech billionaires regularly try to replicate Jobs’s automated approach to dressing. Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg switches between a grey T-shirt or grey hoodie with jeans, while disgraced Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes copied Jobs’s look with a daily black roll-neck.

Diana’s athleisure

By Johnny Eggitt, 1995, and Greg Harris, 2019

As one of the world’s most photographed women, Diana, Princess of Wales, knew that the way she chose to present herself through her clothing was key. From shunning gloves to shake hands with people diagnosed with HIV/Aids to the “revenge dress” she wore the night Charles confessed to having an affair with Camilla, you can trace many key moments of her life through her wardrobe. However, it’s an oversized “Fly Virgin Atlantic” sweatshirt and cycling shorts that, nearly 30 years later, everyone from influencers to high street brands continues to revere. The sweatshirt, originally a gift from the airline’s founder, Richard Branson, sold to an anonymous buyer for over £43,000 in 2019. That same year, in a shoot for Vogue Paris, gen Z’s favourite model, Hailey Bieber, recreated the athleisure look.

Supermodels in white shirts

By Peter Lindbergh, 1988

When Anna Wintour arrived as editor-in-chief of US Vogue in 1988, she found a shot taken by German photographer Peter Lindbergh shoved in a drawer. Featuring six relatively unknown models (from left: Estelle Lefébure, Karen Alexander, Rachel Williams, Linda Evangelista, Tatjana Patitz and Christy Turlington) wearing white shirts on a Santa Monica beach, it had been rejected by her predecessor who preferred traditional glamour. Wintour later ran the shot, and in doing so elevated the humble white shirt to a wardrobe must-have. Four years later, for Vogue’s 100th anniversary, she endorsed it again, when she featured 10 supermodels in shirts tied at the midriff, this time from Gap, making a high-fashion look attainable to the masses.

Madonna’s conical bra

By Jean-Baptiste Mondino, 1990

Madonna’s conical bra, designed by Jean Paul Gaultier, popularised the idea of wearing underwear as outerwear. First worn on her 1990 Blonde Ambition tour, the garment was paired with a pinstriped suit and monocle. Instead of the traditional soft curves a corset created, Gaultier’s version made the body hard and explicit. Combined with the singer’s gyrating dancing, BDSM imagery and religious iconography, the outfit made headlines worldwide.

Pat Cleveland descends at Thierry Mugler

By Paul van Riel, 1984

French designer Thierry Mugler could be credited with creating the archetype of the viral runway show. In 1984, he filled the Zénith arena in Paris with more than 6,000 fans, some even paid for tickets. For the finale, the Black American who saw model Pat Cleveland, six months pregnant and dressed as the Virgin Mary, descend from the roof. As the New York Times said, “The day may never return when fashion shows were simple affairs in which models carried numbered cards down the runways to the sound of buyers and journalists quietly breathing.” .

Naomi Campbell in leather

By Herb Ritts, 1990

This now famous shot of Naomi Campbell – wearingin only a pair of patent leather thigh-high boots and a matching hair wrap – was part of a series by American photographer Herb Ritts that was originally rejected by American Vogue. Ritts became known for his use of natural lighting, regularly shooting on the rooftop of his studio in LA. Drawing on his love of architecture and sculpture, he worked closely with his subjects using props to execute his visual motifs. “The poses could be very hard,” Campbell said. “You’d be in a lot of pain and the sun would be beating down, but Herb would say, ‘Just give me a little more time – I’m going to get it.’”

Marc Jacobs’s grunge era

By Kyle Ericksen, 1992

Taking inspiration from the grunge movement for the spring/summer 93 Perry Ellis collection, creative director Marc Jacobs (in sunglasses) riffed on the clothes worn by bands such as Nirvana, with plaid shirts, slip dresses and beanie hats. The press hated it, Jacobs was fired and the collection never went into production – but then the grunge look took off and in 1997 he landed the top job at Louis Vuitton, who were after a designer to create clothes with youth appeal.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.