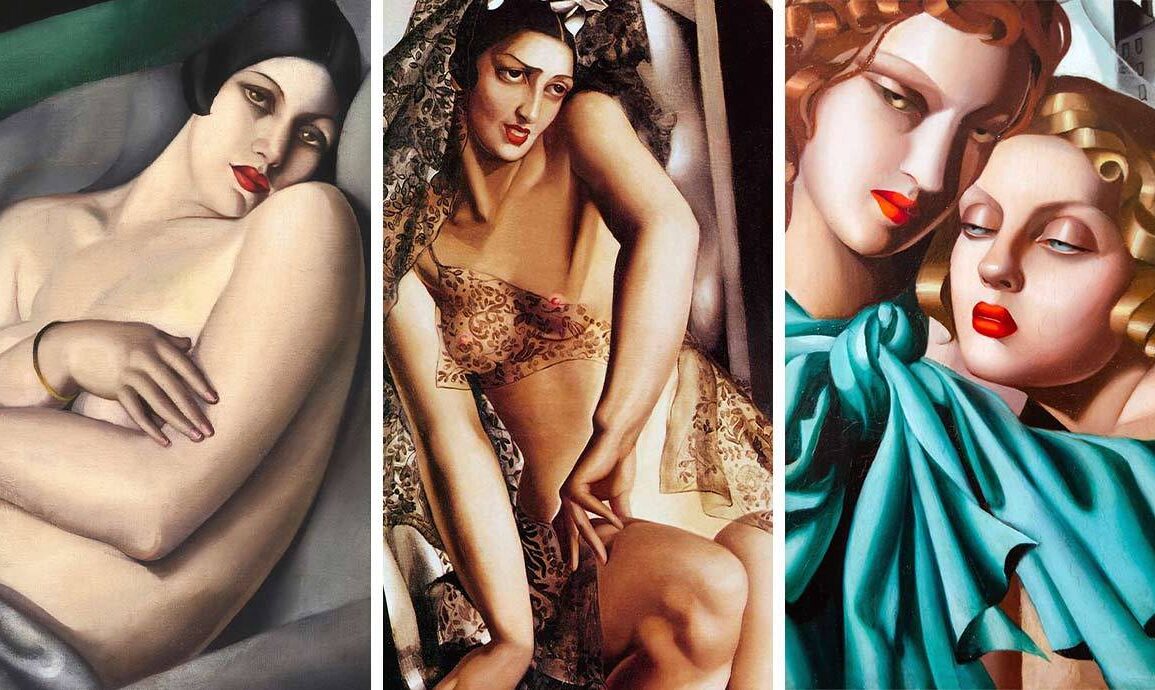

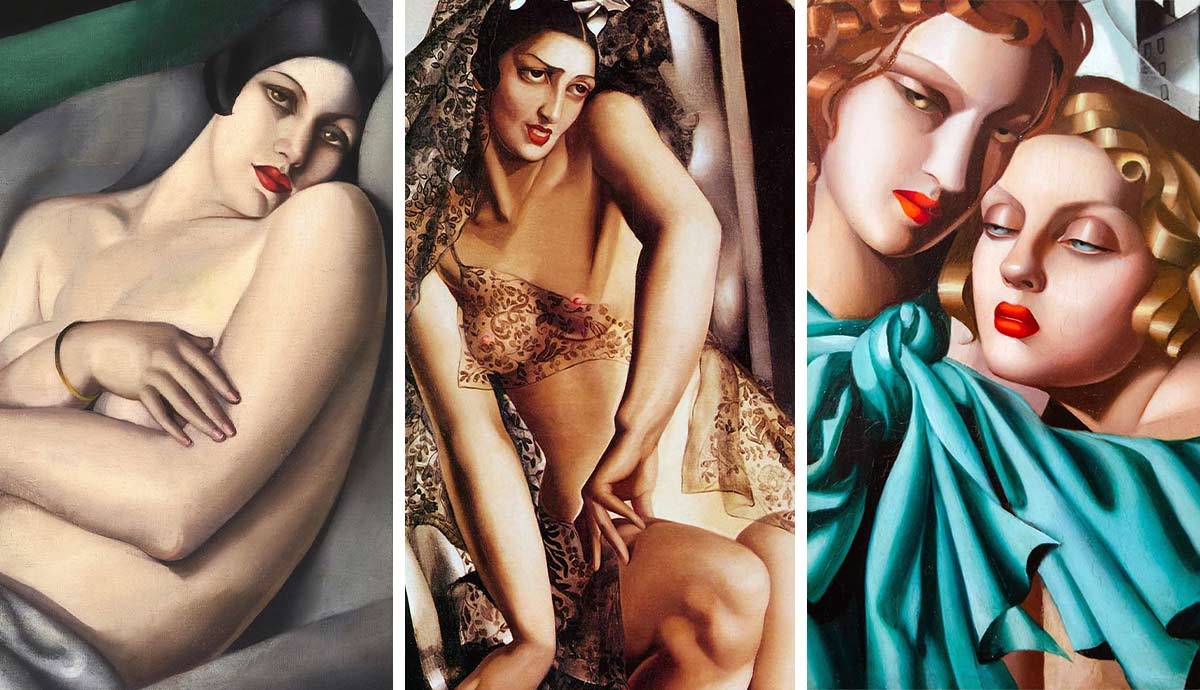

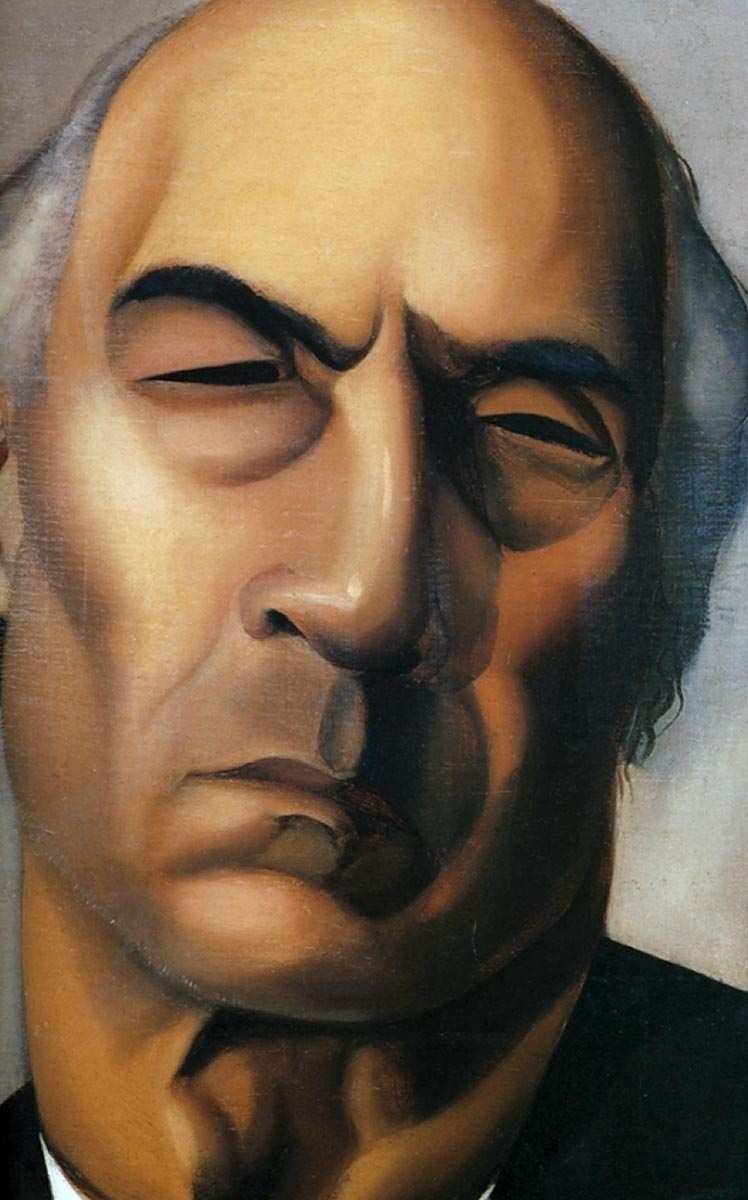

Tamara de Lempicka was the Polish artist who defined the aesthetic of Art Deco and the style of the European Roaring Twenties. She was inspired by Cubism, Neoclassicism, and the latest technology. Critics referred to her as the perverse Ingres of the machine age. During her prime, both men and women fell victim to her charm, and even today art collectors fight for her works.

1. Tamara de Lempicka Constructed Her Fabulous Life From Scratch

Tamara de Lempicka, the great Art Deco artist who embodied the spirit of 1920s Europe, was born in Warsaw in 1898. She had a typical childhood of a spoiled heiress from a rich family. In her late teens, she married a Polish lawyer Tadeusz Lempicki and moved to Saint Petersburg. The following year was an endless parade of restaurants, parties, and champagne flowing until the political turmoil became impossible to ignore. In late 1917, her husband was arrested, and she had to flee to Europe. Tadeusz joined Tamara several months later, but his time in jail affected him greatly.

Lempicka, like many other Russian residents who left their homes during the revolution, found herself in Paris, on the left bank of the Seine. The new life did not bring much joy to her family. Money was running low, Tadeusz refused to work deeming all available jobs unworthy of him, and on top of all, Tamara was pregnant much to her husband’s disdain, who questioned his fatherhood. With matters getting progressively worse, the soon-to-be artist decided to take her life into her own hands.

2. Her Persona Was Her Greatest Work of Art

Tamara’s sister encouraged her to fight for her own future without depending on the strained relationship she had with her husband. So, Tamara started attending free art courses while still managing to take care of the house and her family. No matter how tense the relationship got, she never allowed herself to look bad in public. She was always impeccably dressed and she left the impression of a woman who was in control of her life.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Her attention to detail, manners, and perfect attire worked in her favor in the same way her paintings did. Tamara’s success was almost immediate, but as soon after her career started to blossom, the artist got rid of all the things that could stop her from being an artist. Unfortunately, these things also included her daughter, who was sent to a boarding school. The life Tamara had before settling in Paris – her years in Poland and Russia, her family, and everything that wasn’t sophisticated enough was thrown away in order to create a new identity of Tamara who was an artist, not a wife and mother.

3. She Followed The Latest Trends

Soon after deciding to occupy herself with painting, Tamara de Lempicka started looking for teachers. She was lucky, to say the least, as she learned painting from the great Maurice Denis and Andre Lhote, an accomplished Cubist. Maurice Denis was a famous Symbolist who, along with his colleagues from the group Nabis fought to bring back the decorative qualities of art. The Nabis group liked working with tapestries, ceramics, and interior design along with traditional easel painting. Denis’ penchant for decoration was reflected in Lempicka’s compositions. By the time Lempicka received her training, Denis abandoned his progressive style in favor of Italian Old Masters. Still, his theories on line, color, and the essence of painting remained and proved useful to his students.

Combining her teachers’ influences with neoclassical ideals of art, Tamara de Lempicka became a representative of the new and developing genre of Art Deco. Similar to Futurism in its conceptual undertones, Art Deco also celebrated the century of new technology, machinery, and speed. Unlike Art Nouveau which relied on natural organic forms, Art Deco artists worked with straight lines and geometric forms, cold tones, and glossy metallic surfaces.

4. She Was Friends With The Right People

While her first husband, sulking at Tamara’s accomplishments, still looked for a suitable job, she traveled through Europe, selling her paintings and making friends with important people. She drank tea with Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli, partied with Moise Kiesling and Tsuguharu Fujita, and spoke of literature with Andre Gide and Gabriele d’Annunzio. People were mesmerized by Tamara, and she was ready to use this to propel her career.

One of her friends was the Italian poet and the leader of the Futurist movement, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Once, during a gathering at a brasserie, Marinetti decided to give a speech. The speech was a typical Futurist one during which he called for the destruction of remnants of old culture and art, expressed in burning down the Louvre. Lempicka, who sat next to Marinetti, for a moment shared his enthusiasm and offered to drive both of them there immediately. The plan did not work, however. The police towed Lempicka’s car away for improper parking, the moment was lost, and the museum remained intact.

5. Her Works Hide a Darker Fascist Undertone

Part of what made Tamara de Lempicka’s work immensely popular for a short while was her conformity with fascist aesthetics. Her paintings were monumental, exhibiting the stylized realism that developed from old European art. The subjects of her works (the royals, the actors, the bored wives of bankers) represent the elite and the wealthy, detached from reality in their social bubble filled with drugs, champagne, and gossip. Fascism was unnervingly popular among the European elites at the time, with its ideas being a fashionable toy among intellectuals. Some, like Marinetti and d’Annunzio, were more open to it, and some, like Lempicka, were careful enough to detach themselves before it became too late.

Still, despite her association with many famous fascists, Tamara de Lempicka was never a supporter of Hitler. On the contrary, soon after he seized power she instructed her second husband, an Austro-Hungarian baron, to sell parts of their property and move to the United States. Lempicka was a white blond woman with enough social connections and an artistic style that did not contradict the Nazi’s aesthetic vision. Still, the vision of German crowds marching and chanting slogans scared here.

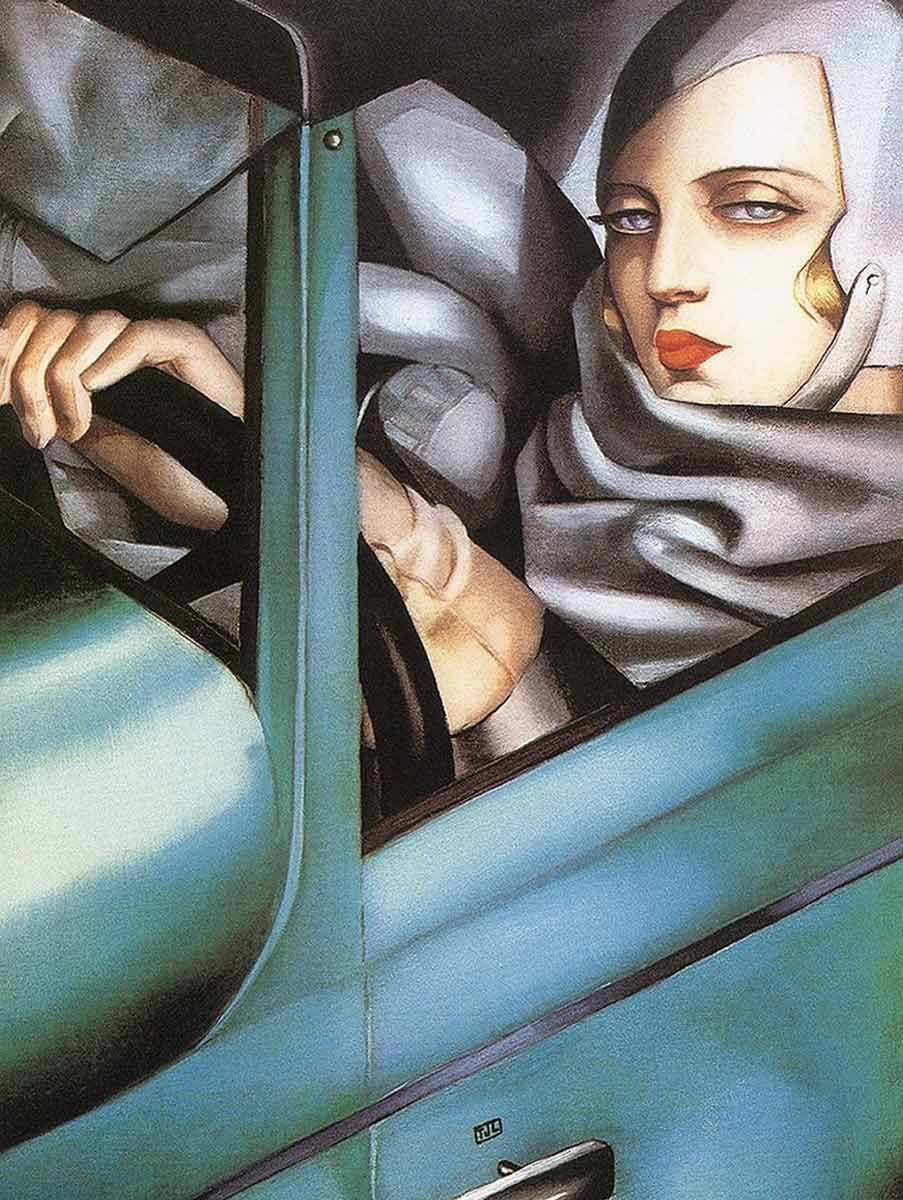

6. She Embraced Her Sexuality

Art historian Whitney Chadwick wrote that a queer expatriate essentially reflected the ideal woman of post-World War I France. She was financially independent, urban, educated, mobile, and not bound by the limitations of old-fashioned morals or cultural prejudices. Lesbian and bisexual women like Tamara de Lempicka (Polish), Ida Rubinstein (Ukrainian), and Natalie Barney (American) dictated fashions, arranged social gatherings, and set standards. The complete and aggressive rejection of old norms became the new norm. Their fashionable looks included short hair, dramatic makeup, and cigarettes.

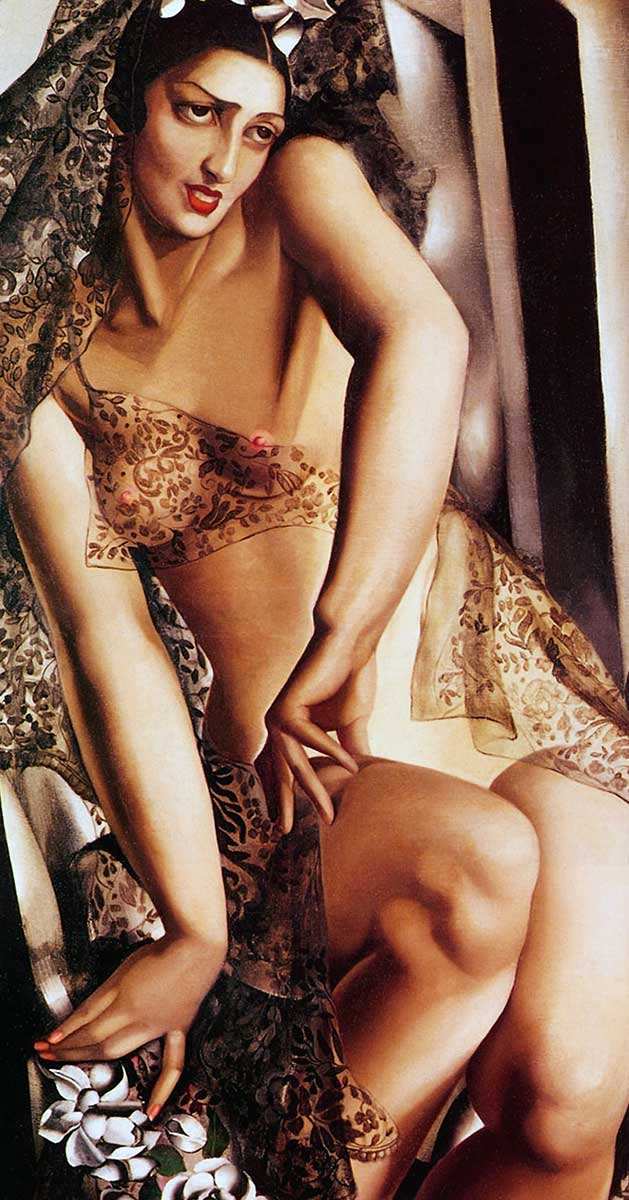

Lempicka’s paintings demonstrated how the new woman of her age was regaining control over her sexuality by setting the rules and choosing the objects of her desire. In many ways, sexual desire was her reason to paint. Lempicka recalled how she once saw a woman’s bare shoulder in opera and was drawn to her immediately. She even convinced the woman to pose for her nude. Lempicka never learned the model’s name, but the painting became one of the most sensual works she ever painted.

7. Her Fame Was Rather Short-Lived

Tamara de Lempicka’s artistic success was almost instant but short-lived. As it turned out, her style was tied to a very specific moment in history, which soon turned into outdated kitsch. The interwar generation, also known as the lost generation, met their mature years with rapid post-war economic growth, trauma left by recent events, and complete disregard for the consequences of their decisions. The rampant party generation of the Roaring Twenties had little regard for the future, so when the future came, it was unable to sustain itself.

Tamara de Lempicka’s return to fame happened during the 1960s with the revival of Art Deco. The 1972 retrospective in Luxembourg became the new highlight of her career, with some works finally selling. Still, she never truly reached the same level of recognition she had before. In her later years, she attempted to switch to abstract art but did not succeed in this. Lempicka explained her withdrawal from art saying she refused all offers and commissions. The truth was there were no commissions to refuse. She spent the rest of her life selling her old paintings and traveling the world. While the lavish lifestyle was still present, the creative spark went out.

8. Madonna Own A Lot Of Tamara de Lempicka’s Works

Tamara de Lempicka’s moment was over relatively quickly, but her influence persisted. Her works still make their appearances in artistic creations, pop culture, and interior design.

One of the most famous admirers of Lempicka’s art is the famous singer Madonna. She owns one of the largest private collections of Lempicka’s art including the portrait of an actress and dancer, Nana de Herrera. Madonna also frequently references Tamara’s works in her music videos.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.