Nail art is one of many beauty practices that emphasizes parallels in evolution across culture and time. The sociopolitical landscape of the nail industry across America highlights the nuances behind the beauty ritual and how it can be framed as a tool for cultural understanding and collaboration.

Black and Vietnamese influence on modern American, and further, global nail culture has been evident over the past 50 years. Especially for those local to Southern California and Los Angeles County. This influence paints a story of class relations, migration, and ethnic identity— stemming from major world events.

The Vietnam War sewed justified division and civil unrest across the nation as many Americans protested against the unnecessary violence motivated by U.S. imperial and capitalistic goals. As a result, Vietnamese civilians fled the country and sought refuge in America. Their presence brought on hostility from many, and support from others, namely American figures such as Tippi Hedren.

Tippi Hedren is an American Hollywood star of the 1950s and 1960s, whose lead role in the iconized 1963 Hitchcock film The Birds garnered her national recognition. By the film’s debut, acrylic nails had already been introduced, but seeing them on the big screen cemented their popularity in the mainstream conversation.

Hedren’s beauty practices became something to watch, which she capitalized off of by the war’s turning point in 1975. After her community work led her to witness the experiences of Vietnam war refugees in California, she set out to aid in their material conditions. Together with her personal manicurist, Hedren trained the first twenty Vietnamese nail technicians who would go on to mobilize an entire generation of Vietnamese and other Southeast Asian community members to enter the nail industry as a means of financial security and upward mobility.

The documentary Nailed It, directed by Adele Free Pham, details Hedren’s influence, the rise of Vietnamese nail shops across America, and Vietnamese and Black women’s contributions to the business. Additionally, the film touches on the cultural and political significance beauty can hold within society.

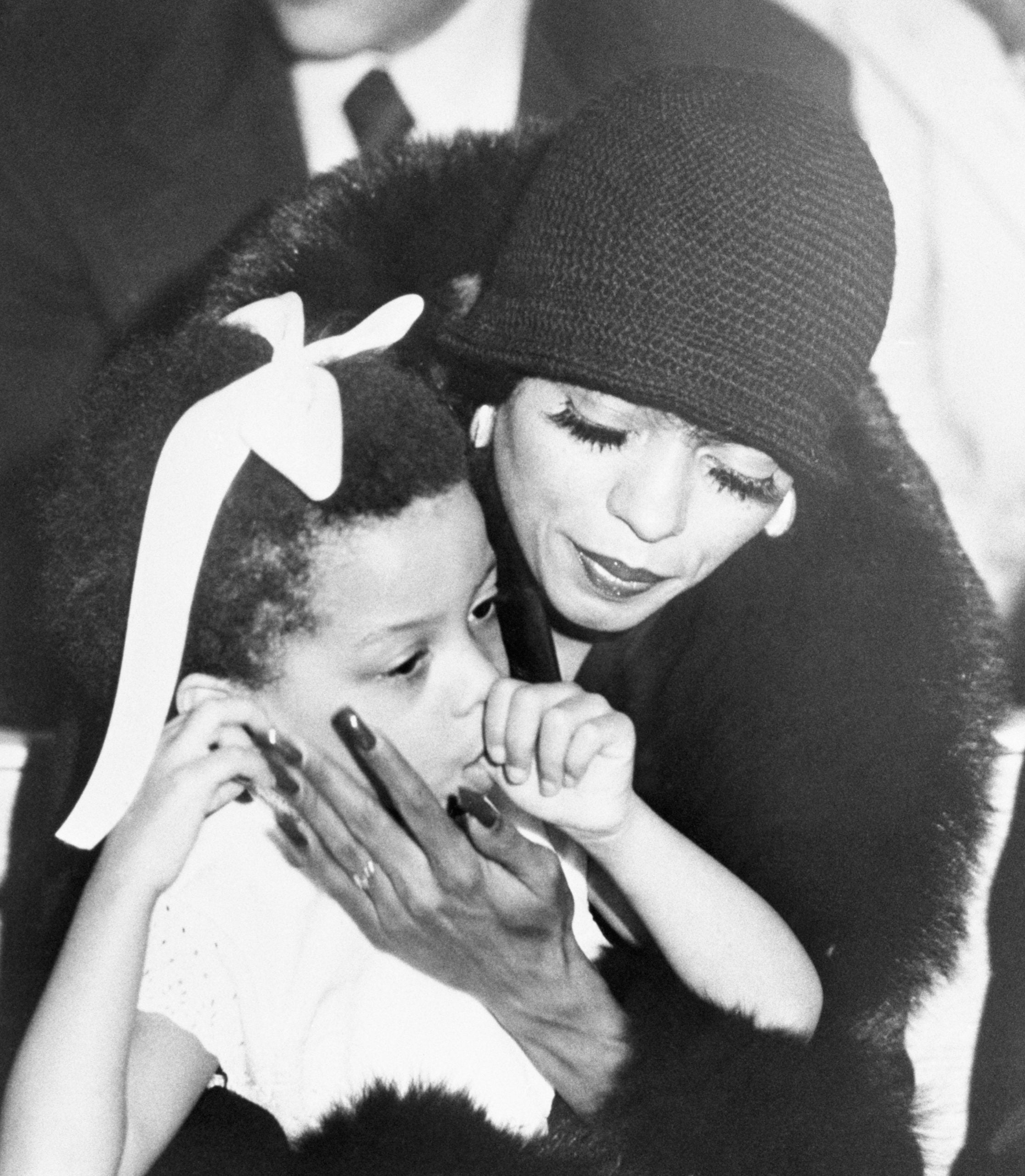

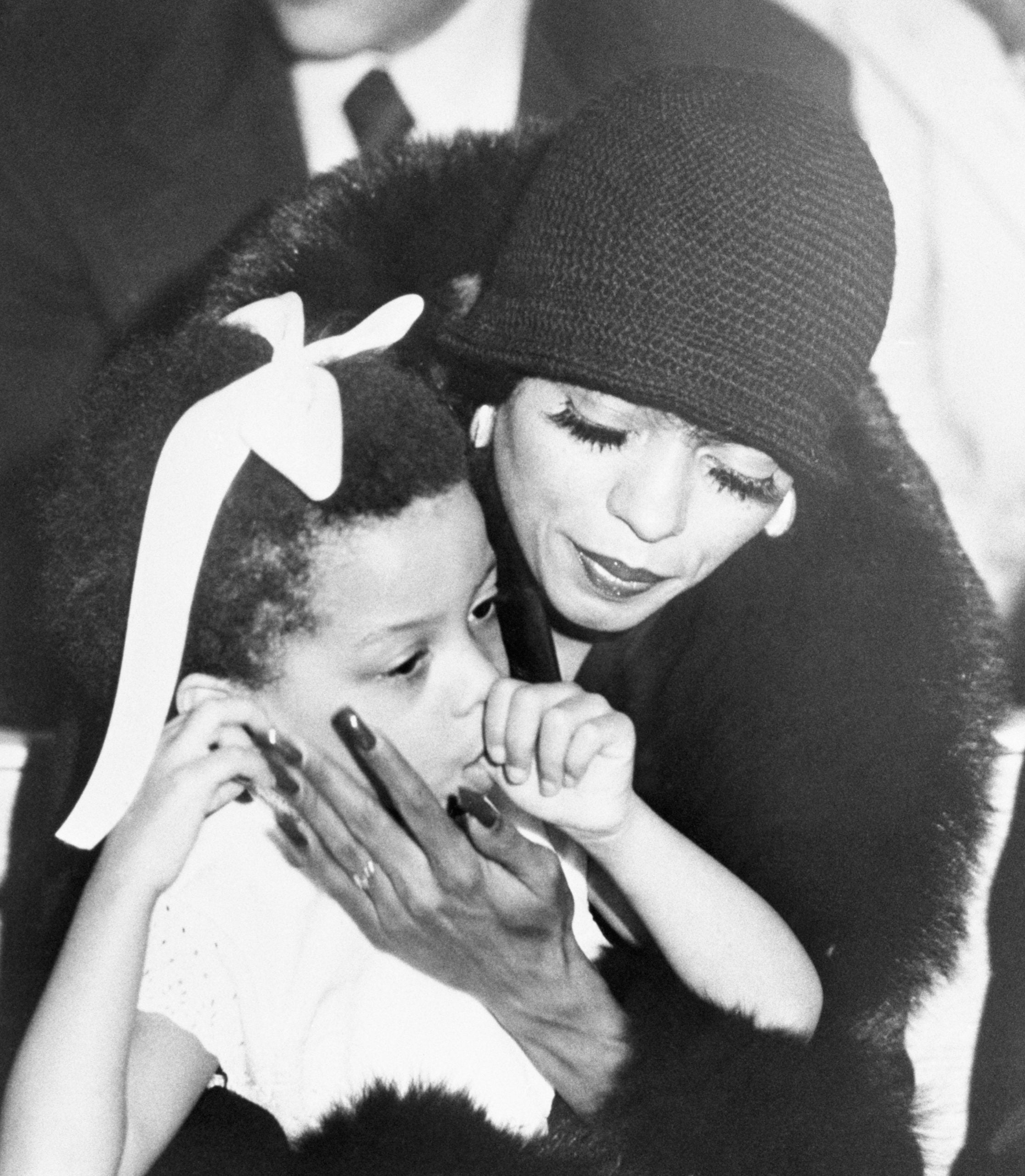

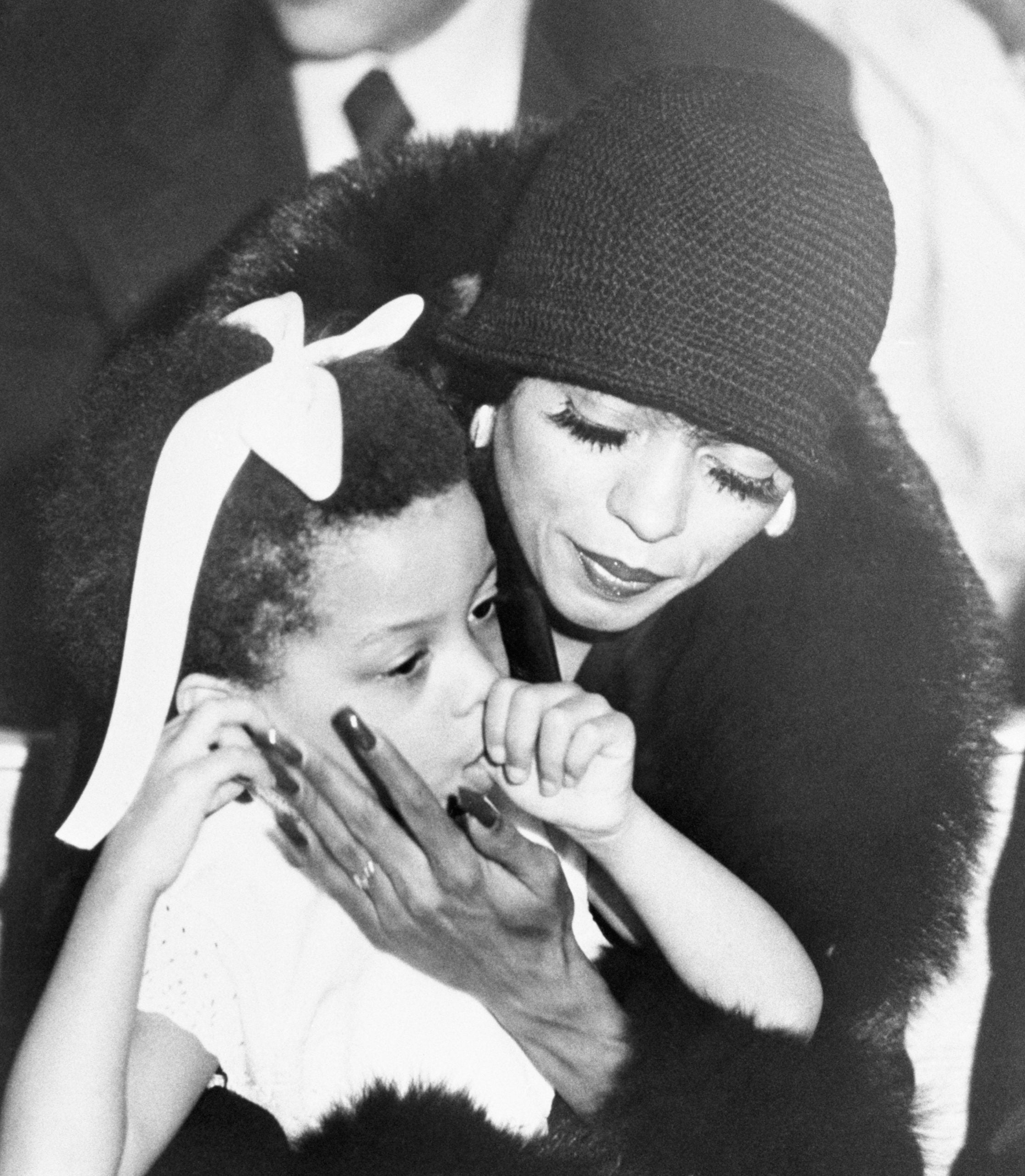

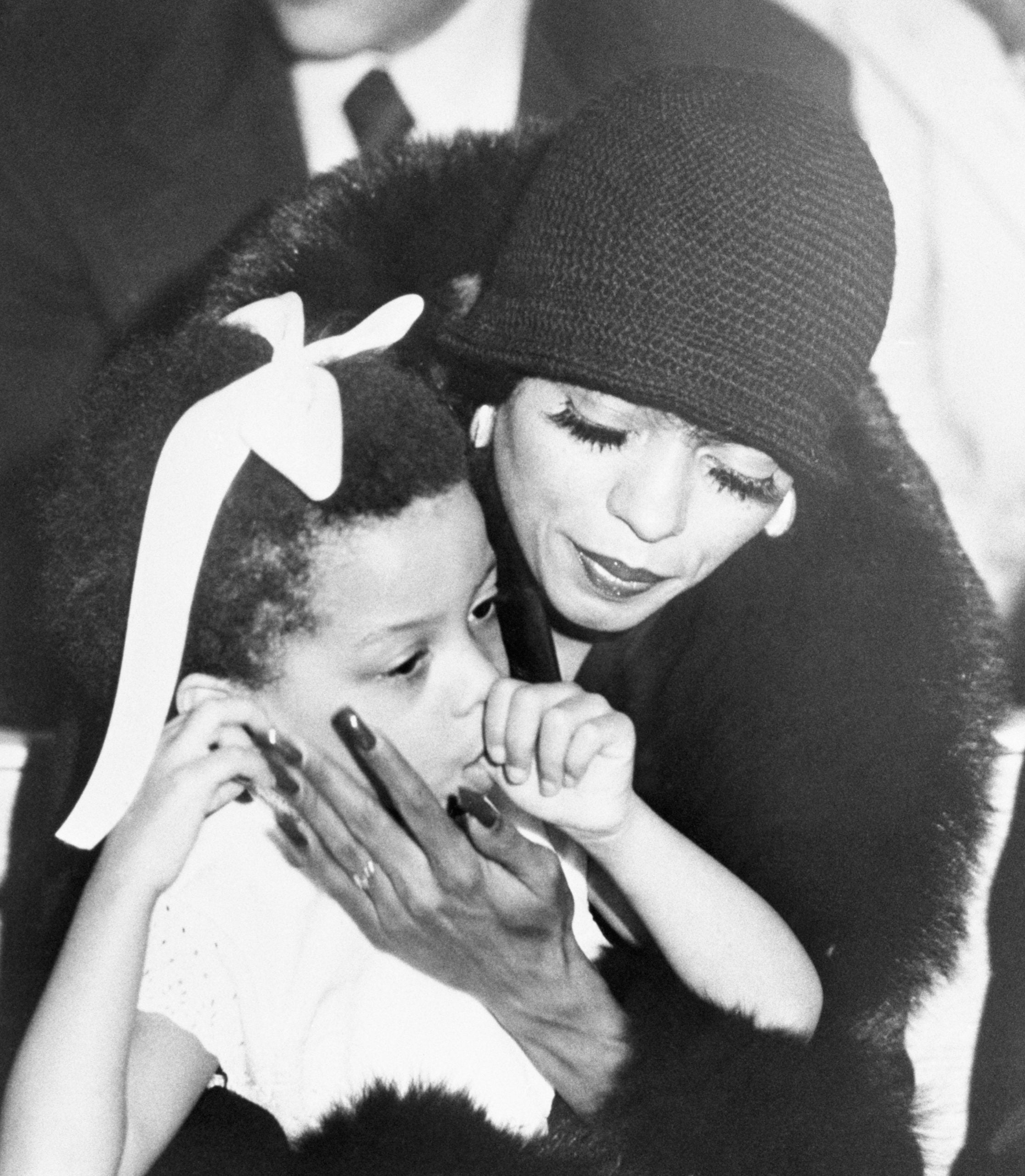

Black women leading the charge on style and cultural innovation is a trend as consistent as time itself. Beauty icons such as Diana Ross, Donna Summer, and Florence “FloJo” Griffith-Joyner set trends and bucked stereotypes with their bold acrylic styles and postured Black women as the face of flashy nail art. Black women’s stylistic influence permeated every layer of culture, originating in the hood, making it to the main stage, and continuing across culture today. Similarly, Wanna Thompson details the importance of nail art for Black women’s personal expression over time and emphasizes its present-day role for many women of color.

The “hood” nail shops, as Kevin Saint Pham affectionately refers to them in the documentary, were the birthplace of modern day nail culture and creativity. By the 1980s Black women frequenting Vietnamese nail shops played an active role in cultivating that avant garde culture and made space for two seemingly different cultures to bond through beauty and art.

A fated collaboration between one Vietnamese nail technician Charlie Vo, and Black salon professional Olivett Robinson revolutionized the hood nail shop and ushered in the first era of nail shop chains.

Their pioneering nail shop “ManTrap” sprouted several locations across South Los Angeles and further developed the American nail industry. Vo and Robinson’s unity epitomized the merging of cultural ingenuity and extended the legacies of marginalized diasporas that utilize artistic expression as a means of survival.

This collaboration, however, was a rarity. Hatred and tension, fueled by anti-Black racism, xenophobia, and white supremacy’s manufactured scarcity mindset, caused strife between Black and Asian communities across generations. Densely populated yet segregated communities consisting of Black American, Black immigrant, and Asian immigrant communities bore exclusionary and, at times, dangerous experiences due to racial profiling on all ends.

The violent murder of 15-year old Latasha Harlins at the hands of Korean store merchant Soon Ja Du in 1991 South Los Angeles painted a sobering picture of the sociopolitical environment that leaves communities of color at odds. Shopkeepers’ racial profiling of Black consumers, along with xenophobic behavior toward non-native English speaking workers, are baked-in social practices that sever ethnic groups to this day.

Having lived in Los Angeles for almost ten years now, there are select Asian-ran Black beauty supply shops that I can no longer bring myself to frequent because of the unsubstantiated accusations, racial profiling, and aggressions I have directly experienced. As transformative as experiences of unity can be, both truths continue to hold weight.

In an earlier conversation with Professor Omise’eke Tinsley discussing the politics of Black femininity, the scholar speaks to the potential of conversations on Asian and Black relations through beauty and politics. She notes that she is more interested in the cross-solidarity opportunities between these groups than marginalized attempts to gain acceptance through beauty standard assimilation.

Tinsley expresses that “Black and Asian women are positioned as opposites in ways that always end up benefiting white supremacy, [but] if we can find a way to work together and have these conversations, it would actually be really subversive.” By subverting these narratives we can pushback on white supremacist notions of beauty and politics that aim to separate us.

Some of the most moving elements of cross-cultural beauty spaces shine through the communal environments they cultivate. The deeply resonant love that nail shop owners have for their longtime customers turned family, and mutual support between Asian merchants and their Black women patronage are poignant reminders of the unifying power beauty holds. Beauty is a powerful tool that, when utilized with compassion, pushes people to see the humanity in each other. A recognition that is vital for movement work and survival.

As complicated as cross-cultural solidarity may be due to the inescapable anti-Blackness that permeates the globe, one fact is certain: we will not reach total liberation by perpetuating the tools of white supremacy— whether via racism, xenophobia, or any other mode. It would behoove us to take heed of Audre Lorde’s caution: “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

The differences and similarities between Black and Asian communities globally are both beautiful and difficult. Still, through universal mediums of self-actualization, such as beauty and commerce, we can find common ground to weather the storms of a global capitalism that plagues all of our respective communities, and threatens our collective existence and prosperity.

Nail art is one example that proves beauty is not simply a practice in vanity. Rather, a means of expression and solidarity.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.