On a sweltering summer evening on the terrace of Le Comptoir des Saints-Pères, a neighbourhood brasserie where F Scott Fitzgerald, concerned over the size of his manhood, once exposed himself to Ernest Hemingway, I noticed a ubiquitous exposure of another kind. Well, two: visible nipples.

They peered through sheer summer dresses, gauzy shirts and superfine tank tops. For a city of women who dress so predictably as to have their collective style coined “iconic”, the brazenness of the act, though eye-catching, felt less provocative and more refreshing and nonchalant with each sighting. Cue an exhale of smoke and a, “Quoi? These old things? Bof. Pas grand-chose.”

Sheer garments are by no means a novel idea in fashion. On the runway and in magazine spreads, an exposed nipple wouldn’t warrant a second look. They were out and proud across the autumn/winter 2023 collections, decorated with egg yolks at Puppets and Puppets and peaches at Melke. At the haute couture shows in July, one could spy a slip of the nip at Schiaparelli, Jean Paul Gaultier and Charles de Vilmorin, to name a few.

However, when translated into the real world, these looks are often altered. At retail, camisoles or slips are layered underneath, or even sewn in, as truly sheer looks have historically felt indecorous at street level. The breast remains one of style’s last taboos.

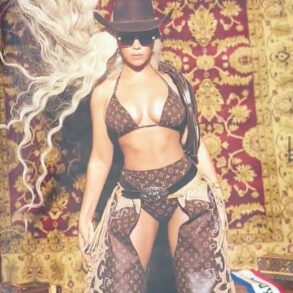

But even beyond the Rive Gauche, points of view are shifting. In January, Meta’s oversight board advised Facebook and Instagram to lift the censorship of women’s nipples — men’s have always been allowed — on their platforms. On the red carpet in February, Charli XCX wore a transparent Ludovic de Saint Sernin dress to the Brit Awards; Rita Ora went braless on the Alaïa front row as did Florence Pugh at Valentino’s July haute couture show. Leonie Hanne, Chiara Ferragni and French actor Rebecca Dayan also showed up on at the Paris couture shows in see-through styles.

Los Angeles-based fashion writer and influencer Alyssa Coscarelli opted out of wearing a bra over six years ago. Going braless under sheer clothing is something she has noticed more and more in LA, as well as in the cooler neighbourhoods of her former home of New York City.

“You’ll see it especially this time of year when it’s so damn hot,” she says. “It’s really a comfort thing at first, but then there’s that secondary element of just embracing our bodies. Why over-sexualise [nipples] on women but then not be fazed by them on men? It just doesn’t make sense to me.”

Coscarelli acknowledges that living in LA and often being in the privacy of her own car helps to make her feel more at ease in sheer clothing. She cites the current “subway shirt” trend on TikTok, where women cover up their summer outfits during their commute with oversized shirts and sweats to avoid harassment or unwanted attention. “It’s quite unfortunate that we have to go to that length to help protect ourselves, but it is a reality in big cities and on public transport. We don’t want to receive unsolicited, unwanted attention from the wrong folks.”

Dr Valerie Steele, fashion historian and director of the FIT Museum in New York, recalls being “young in the ’70s when exposed nipples were nothing. [Women] were wearing sheer blouses all the time without even thinking about it. That was a period when women’s liberation, sexual liberation and gay liberation became a mass movement, it wasn’t just a few people.”

But transparent styles of dress began to appear well before Yves Saint Laurent’s sheer chiffon blouse of 1966. During the Directoire period in the final years of the French Revolution, when women abandoned the cumbersome ancien régime styles of stiffly boned corsets and leaden fabrics in favour of more “natural” muslin gowns that were wetted so that they might cling closer to the body. Female fashion history is full of occasions where the hint of an ankle, an above-the-knee hemline or even the ability to be fully mobile could cause the clutching of pearls. Might the scandal of nipple-baring looks be one day considered just as archaic?

For those not looking to commit to full exposure just yet, Steele points to the nude body prints that Y/Project designer Glenn Martens recently designed for Jean Paul Gaultier as a witty alternative. “Gaultier [originally did them for his Cyberbaba collection for spring 1996] for men and women. He even did a woman’s suit but it looks like a man’s torso on the jacket, which was interesting,” she says. “So I’m finding that the whole nude on the outside of the clothes [to be] a very interesting phenomenon because alluding to nakedness without actually showing it, just showing a picture of it, is a very interesting kind of metaphysical approach to body exposure.”

Paris-based photographer Sylvie Castioni has made challenging perspectives of the naked female body her life-long work. Her recent “Amazones” exhibition at Galerie Duret, featuring proud, commanding nudes of Léa Seydoux, Barbara Palvin, Emmanuelle Béart, Caroline Ida Ours and the late Charlbi Dean of Triangle of Sadness celebrate the diversity and subtlety of female representation, attempting to free women from the external gaze.

“We always associate a woman’s breasts with her sexual reproductive functions. [Women are] constantly reduced to that, and that’s why [exposed nipples can be] shocking. But if we were programmed in a different, deconditioned way, we’d look at women’s breasts or bodies differently, and that’s what I’m trying to do,” explains Castioni, who covered her breast at her exhibition opening with a criss-cross of tape mimicking the censorship of women’s nipples on Instagram. “It was wonderful. I’ve had young girls come up to me crying, taking pictures of themselves in front of my photos and saying, ‘This makes me feel good.’”

Sign up for Fashion Matters, the FT’s weekly newsletter on the business of style

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.