There are more reasons than not to call Jesus a rapper. By the definitions of his day: a gangster rapper. Check the Bible, it’s all in there—a young ruffian delivering verses on street corners amongst society’s outcasts, labeled a dangerous thug by an oppressive government, judged by a self-serving, holier-than-thou church system. Constantly broaching subjects forbidden by the establishment, performing for enraptured crowds hanging on every word, making brazen scenes in public,, and he’s not a white guy? Let’s call it like it is, Jesus is a rapper.

If Christ then was Biggie (apologies to 2Pac), the twelve apostles — Peter, Andrew, James, John, Philip, Bartholomew, Thomas, Matthew, Jude, Simon, another James, and that mark snitch Judas — were Jesus’ Junior M.A.F.I.A, whom in the New Testament, he endows with verbal skills using an aura called the Holy Spirit. A pretty serious cypher breaks out in Acts, 2:4, as the Spirit suddenly causes the disciples to begin speaking in tongues and chanting rhythmically—obviously early freestyle and beatboxing.

Throughout the Bible, and still today in revivalist churches, this Spirit has been said to descend upon entire congregations, sending them into joyous mass hysteria, and hurling worshipers, shaking and squirming, into inadvertently awesome breakdance fits. Between gangster rap Jesus and these Holy Spirit b-boys, it’s fair to say God has been sponsoring hip-hop for millennia (Happy 2,030th Birthday?), and as we’ll see, Christian rap may just be the form’s most logical sub-genre.

OLDEST TESTAMENT

Some rap historians posit southern US gospel quartet The Jubalaires’ 1944 song “Noah”—a narrative of the Book of Genesis tale of Noah’s ark—as not only the first Christian rap song, but the first hint of recorded rap, period. (Striking similarities do exist between the vocal stylings used in “Noah”, and those in Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight”.) Whether or not The Jubilaires’ syncopated speak-singing in rhythmic cadence checks all the boxes for busting a verse, it definitely forecasts what came to be known as rapping.

FIRST COMING

The first official Christian rap song in the annals of hip-hop is widely recognized to be MC Sweet’s 1982 release, “Jesus Christ (The Gospel Beat)” , an 11-minute roller-rink jam reminiscent of a rowdy southern church service, random praise shouts, congregant clap-alongs, big lady-choirs and all. As in “Noah”, clear and rapid rhythmic talking is used to convey a Bible story, this time that of Adam and Eve from the Book of Genesis. MC Sweet penned a fantastic hook, so catchy it earned a 1989 7” vinyl re-release on major label Polygram, this time as the 5-minute “The Gospel Beat (Adam & Eve)”.

In the mid-80s, positivity was still a main message in rap music, with words of praise much more commonplace than obscenities. Embodying the trend in 1984 was “Mr. T’s Commandments”, a kid-centric rap, featuring you-know-damn-well-who, praising Moses and God’s ten big rules—while in the video, body-slamming all who walk towards him, throwing fools down warehouse staircases and through glass windows in bars, then bending their weapons in half by hand. T gave no shits for the devilish, but loved parents, and followed this jam with the Godly “Treat Your Mother Right” single.

The flourishing of faith-rap continued in ’85 with Stephen Wiley’s “Bible Break” single—a bare-bones beat replete with zappy shopping-mall synths and Bible-shaped boombox cover art. Later that year, Texas natives The Rap-Sures released Gospel Rap, what has since come to be known as the first full Christian rap album. Racked with hokey voices, and novelty shop side-showery (plus a manic, crowded mix job), the cheese of Gospel Rap hasn’t aged well, though The Rap-Sures did indeed break new ground.

RISE OF THE RIGHTEOUS

Amazingly, what is considered to be the “big bang” of Christian rap occurred thanks to a posse beef, complete with a diss track. In 1986, New Jersey-based Christian rappers Crew Devastation released four singles, all God-centric, before New York rival Doug E. Fresh dropped “All the Way to Heaven”, from his Oh My God! album. Having already gathered a strong following from hits like “The Show” and “La-Di-Da-De” with Slick Rick, Fresh was a household name in rap, so when he rhymed about the Big Guy, the culture at large began to credit him with breaking ground for God.

Meanwhile, across the Hudson, Crew Devastation was pissed. As OG God-rappers, they saw “All the Way…” as a style-bite from a young star in search of trends (Watch that tenth commandment boys!). The specific lyric, “Messages from God sent through me/I’m just like Moses, no one knows this”—what the hell did he mean no one!?—is said to have driven the Crew to record the retort single, “We’re all Going to Heaven”, a reminder to Fresh, without calling him out, that they were headed upstairs too…and Doug E. didn’t really listen, let alone care, and they all lived happily ever after.

CREWS STRAIGHT OUT THE PEWS

Far off on the west coast, the first real-deal ordained pastor in Christian rap, Reverend Rhyme, had just released his “According to Rap” album, a collection of basic moralistic teachings for kids delivered in a tone that resembles Bad Brains’ H.R. doing RUN-DMC, with some touches of ODB for good measure (see “The Devil, The Big Lie”). It’s actually surprisingly badass, but the true reverential rap-ture was to come later that year, from the pen of The Rappin’ Reverend Dr. C. Dexter Wise, III, pastor of Columbus, Ohio’s Shiloh Baptist Church.

The Rappin’ Reverend’s “I Ain’t Into That!” is just about as smooth as any innocent song is allowed to be, a top-down cruiser with a type of chill flex even non-puritanicals struggle to pull off. For six minutes, The Rappin’ Reverend grins and bops through a Biblically-informed list of his lifestyle will’s-and-wont’s, sounding like a sanctified Eazy-E stuntin’ on the pulpit. As overall flavors and feels go, dare it be said, “I Ain’t Into That!” manages to exude some iconic Ice Cube “Today Was a Good Day” vibes.

After an initial release on Shiloh’s own Raise Records, “I Ain’t Into That!” was picked up by a European label, and by years’ end, the song had somehow reached #14 on the UK national dance charts. Wise’s full-length debut came in ’89, with the ultra-rare Crack Attack! album — C. Dexter Doc versus the verminous rock — the cover art for which seems to feature the Reverend sitting and standing at the same time, a none-too-quiet announcement that miracles are happening inside the vinyl’s gatefold.

Another church-issued rap album came in 1988, when gospel label Raytown Records released We Rap Too, a compilation of aspiring rhymesters from a house of worship in Kansas City. The stars of the show are definitely The Rapping Grandmommas, who are just what they say. Six years later, group-leader Ms. Mattie dropped her I’m Your Grandmomma album, featuring the safe-sex message “She Was 13”, and the honestly intimidating scold-rap, “Don’t Raise Your Voice in My House”.

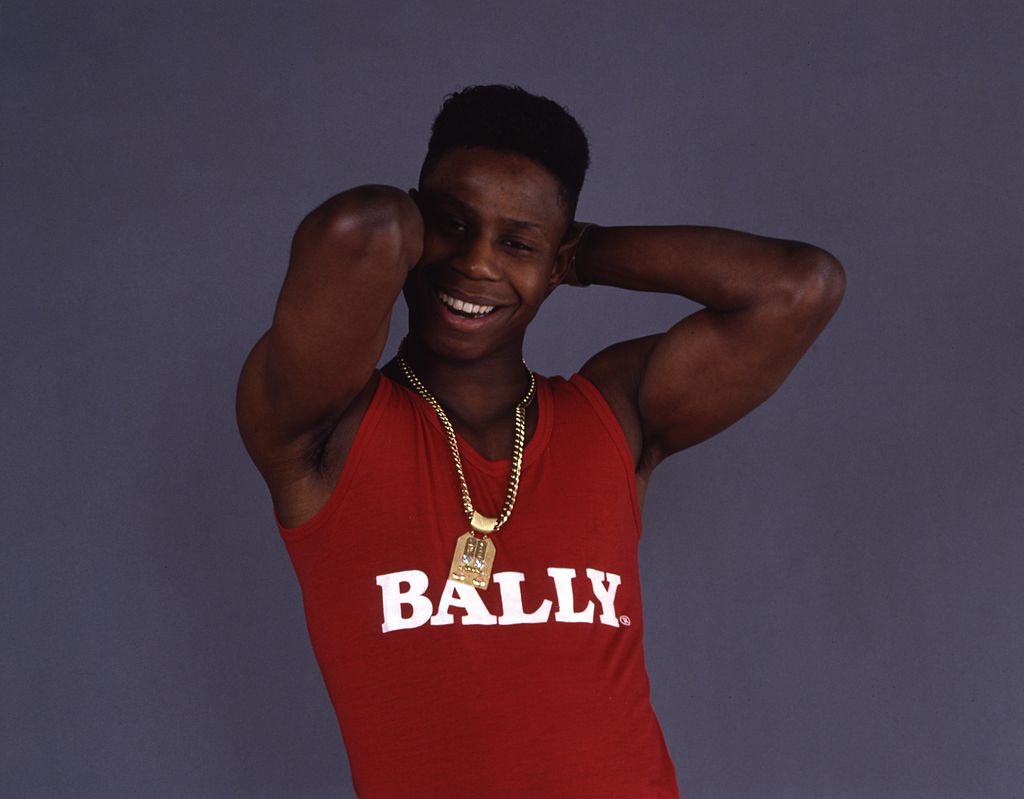

DC TALK BAPTIZES THE MAINSTREAM

In 1989 a Virginian MC trio called DC Talk (short for “Decent Christian”), became the first to break God-rap in mainstream with their self-titled album and breakout single, “Heavenbound” (a surprise hit on Black Entertainment Television music video shows). The cause was furthered in 1990 with “I Luv Rap” and “Can I Get a Witness” (goth standouts from DC’s Nu Thang album), as well as a live appearance on The Arsenio Hall Show, after which Nu Thang went gold, a historic achievement for Christian musicians of any style.

Both LPs were huge pop-culture achievements for the church, though early DC Talk’s wonky music videos, forced hip-hop fashion choices and awkward rap-posing (see their cringey “Two honks and a negro servin’ the Lord” Arsenio Hall commercial), fueled the still-lingering perception of Christian rap as a square, wince-worthy format. But who can blame the listening public — a sterilized Color Me Badd doing divine Vanilla Ice? Surely the creator of the sun, moon, and stars could’ve done better.

GETTING NICE IN THE NINETIES

And do better God did, that same year, with the low-key-holy De La Soul-isms of The Original Dynamite’s The Only Way LP, and its standout single, “Being For Real”. The sole release from suburban-Newark, NJ independent label Cliché Records, The Only Way is a surprise banger— the title track that summons early Wu-Tang vibes, years before RZA’s first demo—and dare be said, a forgotten classic. A Google search returns but two results: a YouTube album playlist and a global vinyl sales site, with only two copies available (start tithing, the record routinely pulls a cool hundo.)

In 1993, an adult-Fred-Savage-looking guy named Carman (pronounced car-man: why?), lowered the mass appeal of Christian rap several notches with “Who’s In The House (J.C.’s in the House)”. Yes, our hindsight lacks context — Carman’s half-speed MC Hammer flow over running-man, TLC-R&B beats may have hit just right in those days — but these days, despite a Gen-X dream-level video with great Kani and Cross Colours fits — “Who’s in the House” holds up like soggy communion wafer.

By the mid-90s, a growing national trend of local Christian cable access shows had granted aspiring Holy hip-hoppers free reign to get loose in a completely non-cathedralic atmosphere. Christian breakdancing flourished (who else but Jehovah could give a Patrick Bateman-esque Caucasoid pop and lock moves like these?), as did Kidz Bop-style God rapping (while also serving as your own hype-man and dancer with DJ-cratch beatboxing? C’mon now, that’s completely God-given.)

IN THE NAME OF GOD

By the early 2Ks, Christian rap had dipped below the mainstream radar, and flimsy FM-radio party-rap — remnants of the P Diddy-ian “Shiny Suit” rap style — had risen to prominence. God though, remained a popular lyric among plenty of “not exactly Christian rappers”, like Scarface, Eminem, The Game, DMX, Kendrick Lamar, Rick Ross, and countless others, most of whom uttered the Holy name while lamenting fate and seeking salvation in sticky situations. Turns out however, when many rappers mention the name God in a verse, it has nothing to do with Jerusalem’s finest.

The Five Percent Nation, a sub-sect of Islam popular with the game’s biggest rappers, is built around the spiritual concept that all black men are in-and-of-themselves Gods, so to remind and reinforce the inborn divinity of their people, Five Percenters greet one another as “God” (spoken in the same context as “dude” or “man” — “What’s happening God?”). Five Percent talk peppers massive amounts of 90s New York hip-hop, including almost all Wu-Tang records (every member has, on and off, followed the Five Percent), and can still be found in much of today’s rap.

CHANCE THE RAPPER

When it comes to modern mainstream Christian rappers, Chicago native and former North Hollywood resident (a place he now calls “ungodly”), Chance the Rapper is easily the game’s shiniest, happiest example. After fleeing the faith in 2011 for secular living as an industry-fave, Chance returned to Christianity in 2016 after his daughter was born with a heart murmur. A thorough life-cleansing followed — drugs, drink and cigarettes, all out the window — documented in detail on his third full-length: the gospel-tinged Coloring Book.

In 2017, the Grammys took notice of Coloring Book, proffering Chance 7 nominations, 3 of which — Best New Artist, Best Rap Performance, and Rap Album of the Year — he took home statuettes for. Never before had a Christian rapper won a Grammy in a standard rap category, and that same evening, a house-rousing performance with gospel legend Kirk Franklin cemented Chance as an rap disciple in the truest sense. His major label debut, The Big Day, was released in 2019 to praise from believers both new and old.

Despite a proclivity for political activism (naturally, as his father was an Obama appointee and aide), Chance remains remarkably nonabrasive, promoting God-policy over lockstep partisanship. With a legit flow, all-welcoming demeanor, and (at worst) PG-13 music, Chance continues to chart hard while pulling top-notch, family-friendly feature spots: hosting Nickelodeon’s Kid’s Choice Awards, a character voice in The Lion King reboot, and this year, a seat at the judge’s table on NBC’s The Voice. Dude even got his own Ben & Jerry’s flavor. Yes, God is good.

YE

In 2016, the main-est of all mainstream Christian rappers and fellow Chicagoan Kanye West, announced that after twenty-plus years of standard rap (“Jesus Walks” talks, but is it Christian rap?), he would no longer be making secular music—only gospel. Ye followed the pronouncement with his Jesus is King album, a set of through-and-though God-rap, received with hesitance and tepid ears among Christians and atheists alike.

At least its lead single, “Follow God”, (sampling gospel group Whole Truth’s “Can You Lose by Following God”), just plain slams—while also renouncing overindulgence in lusts of the flesh and impious earthly appetites. Album closer “Use This Gospel” features the Clipse, whom Ye works no small miracle upon by getting them not to drop drug-raps, until…wait, is that? Yes, it’s Kenny F’ing G, busting sacred sax solos imbued with God-glow.

Now here’s a mind-blower: upon release, Jesus Is King occupied the entire top 10 spots on Billboard’s Hot Christian Songs chart (The only song that didn’t chart was the album intro “Every Hour”, which features only a choir), making Ye, by industry measure at least, the most successful Christian rapper of all-time. Whether Ye lives what he breathes is still up for debate—the Christian indispensables of generosity and humility still aren’t his strong suits.

SNOOP

Another once-deviant, now delivered, the Snoop D-o-double-g worshipped 2009-2011 with the Nation of Islam, then converted to Rastafarianism in 2012 after a Jamaican Rasta-priest identified him as a reincarnated lion. Sooo … after that didn’t work, Snoop inched toward Yahweh in 2016, posting an Instagram Reel singing the gospel stalwart “I’d Rather Have Jesus”. That faith stuck, and after two years spent building a Christ-life, Snoop dropped his gospel double-album “The Bible of Love” in 2018.

The online zealots mumble-grumbled about about Snoop’s limited involvement in his own album—outside artists appear on 30 of its 32 tracks—so the Doggfather shifted stance again, condemning hard-right Christian holier-than-thou’s for over-shaming sinners and outsiders (a completely viable gripe, as man’s Christian church does play pick-n-pull with Jesus’ teachings.) As of this publication though, Snoop remains a proud and avowed God-dog.

PHANATIK

Not all Christian rappers end up holy-ever-after. In 2022, two-time Grammy-nominee Phanatik, a former Lacrae collaborator and founder of Christian rap collective The Cross Movement, publicly renounced his faith after a 30-year career—one serious shift for a Bible college grad, with a Seminary Master’s, five published books on Christianity, teaching positions in multiple religious charter schools, and a professorship at a biblical studies institute.

Citing the sway of liberal theologians for the dissolution of his faith, Phanatik is a perfect example of the damage that an irreligious culture rife with spiritual suspicion can do to a Christian rapper. To escape the daily doubt-dousing and shuns from athiests, modern Christian rappers need nearly hide their faces to avoid instant recognition—as Jesus himself did post-resurrection in the Gospel of John, while walking past Roman soldiers on Easter morning.

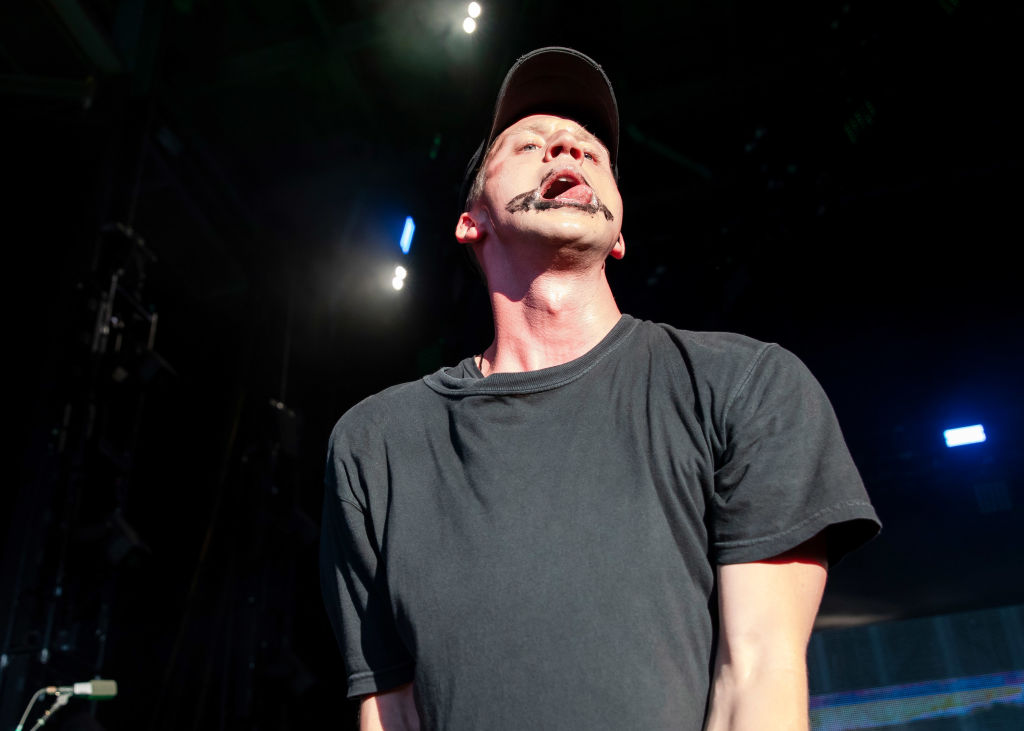

NF

Could such covertness be the way of NF, one of modern Christian rap’s true breakthrough artists, who depending on who you’ve been talking to, has either definitely been Jesus-cloaking, or is plain-and-simple wimping out on his faith after going big-time? Many deep fans say it’s the latter, and have taken NF to task for reducing his God-talk in the glare of stardom.

Then again, just what if, in a nation as hyper-polarized as eagerly venomous as ours, dropping ultra-positive regular music as a regular musician (“a Christian, but not a Christian rapper”, as NF calls himself), while still a newcomer, is better long game for spreading God’s Word than kicking the industry door in waving the Holy flag?

The equation is logical: First winning over listeners accustomed to nonstop guns-drugs-sex rap — while keeping it 100% positive — then, trust established, presenting Jesus in a manner that piques interest within the spiritually curious without scaring off the hesitant, seems the best way for a Christian MC to further the gospel, without being bombarded into agnosticism by trolls and agitators.

LACRAE

Even Christian rap’s most seasoned, most accomplished, and most always-been-Christian MC, Lacrae, may be Jesus-cloaking. The 43-year old Houston, TX, native has dropped 11 mostly-God albums over a 20-year career (with 7 Grammy nominations, and a Best Gospel Album award for his Gravity LP), but recently told the Miami New-Times — in near-verbatim to NF — “My music is not Christian, Lecrae is.”

He continues: “I think Christian is a wonderful noun, but a terrible adjective. Are there Christian shoes, Christian clothes, Christian plumbers, Christian pipes? Labeling it with the faith assumes that the song is going to be some kind of sermon.” And who can argue with that?

THE HOUR OF JUDGMENT

The devout may call it weak of faith — likely those who can’t grasp the disdain for the Christian church that major media seeds among liberal agnostics. Likely those so surrounded by believers, and so accustomed to over-the-top mega-churches that they’ve forgotten, whether concert or chapel, it’s hard to reach a new flock using heavy hands. Regardless, the concept of a Holy Trojan Horse for a Christian rapper makes perfect sense, though do let it be said — should said rapper not eventually speak God’s name after breaching the industry walls — and if the wrath of God is a real thing — all woe be unto him.

So, does the number of Jesuses spoken within a song determine its “Christianity”? Or can positive songs serving and citing the strict principles of Christ, but not dropping the name, be considered “Christian music” as well? Is the NF song “The Search”, with YouTube comments like: “0% violence, 0% drugs, 0% naked girls, 0% swearing, 0% racism, 100% pure talent. This is REAL music”…really “Christian rap”? That answer belongs to the Most High, for as 2Pac was so want to remind us, “Only God Can Judge Me”.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.