One Woman’s Unreciprocated Love For Hip-Hop

Writer and activist Drew Dixon fell in love with hip-hop, but that relationship became complicated as the music became blatantly misogynistic and homophobic.

By Drew Dixon

Aug. 30, 2023

The world celebrated the 50th anniversary of hip-hop this summer, but as anticipation increased for this enormous milestone, I found myself bracing for impact. As a woman in hip-hop, this culture is a source of tremendous pride and unspeakable pain.

Like so many people in my generation, I fell in love with hip-hop as a kid. I remember buying the 12-inch single for “Rapper’s Delight” at a hardware store on Martha’s Vineyard (of all places) in September 1979. I was so taken with this new art form that I glued the sleeve of the record on the wall over my bed in the house my family rented across from Inkwell Beach. I’ve been a hip-hop junkie ever since.

Just over a decade later, I drove across the country from Stanford University to New York City, where I began my quest to make rap records. In the summer of 1994, after 18 months of interning and answering phones at various music industry companies, I finally got my dream job. Russell Simmons, “the undisputed king of hip-hop entrepreneurs,” according to a 1995 Los Angeles Times article, hired me to join the A&R department at Def Jam.

I was good at my job.

When reviewing the paperwork for Method Man’s unreleased debut album, ”Tical,” I had the idea to turn one of the acapella interludes on the album into a duet with Mary J. Blige.* I pleaded with Simmons to let me try it, and eventually, he relented, sort of. He told me that if I could get the New York R&B singer to record vocals for the duet, he would tell Def Jam president Lyor Cohen to open up a budget for the song. So I shared the interlude with Puffy, who had a brilliant concept for Blige to sing the chorus from the Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell classic “You’re All I Need To Get By.” Puff recorded Mary’s vocals, which, along with Method Man’s interlude, became the basis for “I’ll Be There For You (You’re All I Need To Get By),” a song now regarded by many as hip-hop’s greatest love song.

I was thrilled with the outcome, but I was not rewarded or even credited for my work.

A few months after I conceived the song that won Def Jam its first Grammy, a devastating injury that nearly destroyed me. I have discussed those events elsewhere and will not detail them here, but my relationship with hip-hop has never been the same.

While my horrific personal experience does not reflect the entire culture, the undeniable and heartbreaking truth is that hip-hop has always reinforced toxic masculinity. However, back in the early ’90s, as a determined young woman enthralled by the irreverent bravado of rap music, I ignored the red flags and fell in love with hip-hop’s potential. I devoted the first decade of my professional life to the misplaced belief that I could play a part in ensuring that the genre’s most uplifting elements would prevail. The opposite turned out to be true.

Guided by profit-motivated executives with little or no connection to the Black community in which hip-hop began, misogyny, homophobia, materialism and nihilism in rap music and rap marketing proliferated. The research bears this out. Studies by Ronald Weitzer and, Charis Kubrin, and Ellen Chamberlain confirm that the prevalence of misogyny in hip-hop has increased over the years, but even in earlier work by Tricia Rose, Gwendolyn Pugh and Joan Morgan, who coined the term “hip-hop feminism,” critics and scholars have been grappling with the denigration of women in rap music before the turn of the century. So, while the callous disrespect of women in rap music has gotten worse, it’s certainly nothing new.

Way back in 1987, in “The Bridge Is Over,” a foundational song in hip-hop’s canon, KRS-One brazenly asserts that pioneering rapper Roxanne Shante “is only good for steady fucking.” Shante was only 16 years old at the time, but that wildly inappropriate lyric went unchallenged. No one even blinked. In spite of the fact that hip-hop was born at a party organized by Cindy Campbell, an innovative 15-year-old girl, hip-hop culture has never been a safe space for women.

‘You never thought hip-hop would take it this far.’

Rap music is certainly not the only misogynist musical genre in American culture. Far from it. Hip-hop, like all manifestations of pop culture, reflects the values in the broader society. Hip-hop emerged and continues to evolve in a country where in 2023, a legally verified rapist who once admitted on a hot mic to grabbing women by the pussy is leading in many presidential polls. Other genres of music, from rock to country, including artists like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, have glorified domestic violence and statutory rape. Unlike most other forms of pop music, however, hip-hop wants to have it both ways.

The corrosive paternalism of rap music is shrouded in the patina of upward mobility and Black empowerment. As a result of this stylistic head-fake, many female hip-hop fans have been seduced by the allure of fighting the power in an environment rife with degradation. Hip-hop has not only failed to deliver on its early nod to Black liberation. This powerful global art form reinforces white supremacy. By amplifying toxic tropes about the hypersexuality and worthlessness of Black women and girls, rappers unwittingly echo ideologies used for centuries to normalize the rape of our enslaved ancestors. Hip-hop has morphed into a worldwide distributor of misogynoir, gaslighting Black women and girls worldwide to hate themselves and accept the absolute least.

When I fell in love with artists like Brand Nubian, De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest three decades ago, I could not have imagined what hip-hop would become. As my dearly departed friend Biggie said in 1994, “You never thought hip-hop would take it this far.” He was right. In the 30 years since he dropped that iconic line, hip-hop culture has transformed fashion, film, fine arts, video games, dance, politics, comedy, literature and, of course, music around the world. There is so much to celebrate, but it is impossible not to feel regret about the lost opportunity to build something more meaningful with this momentum.

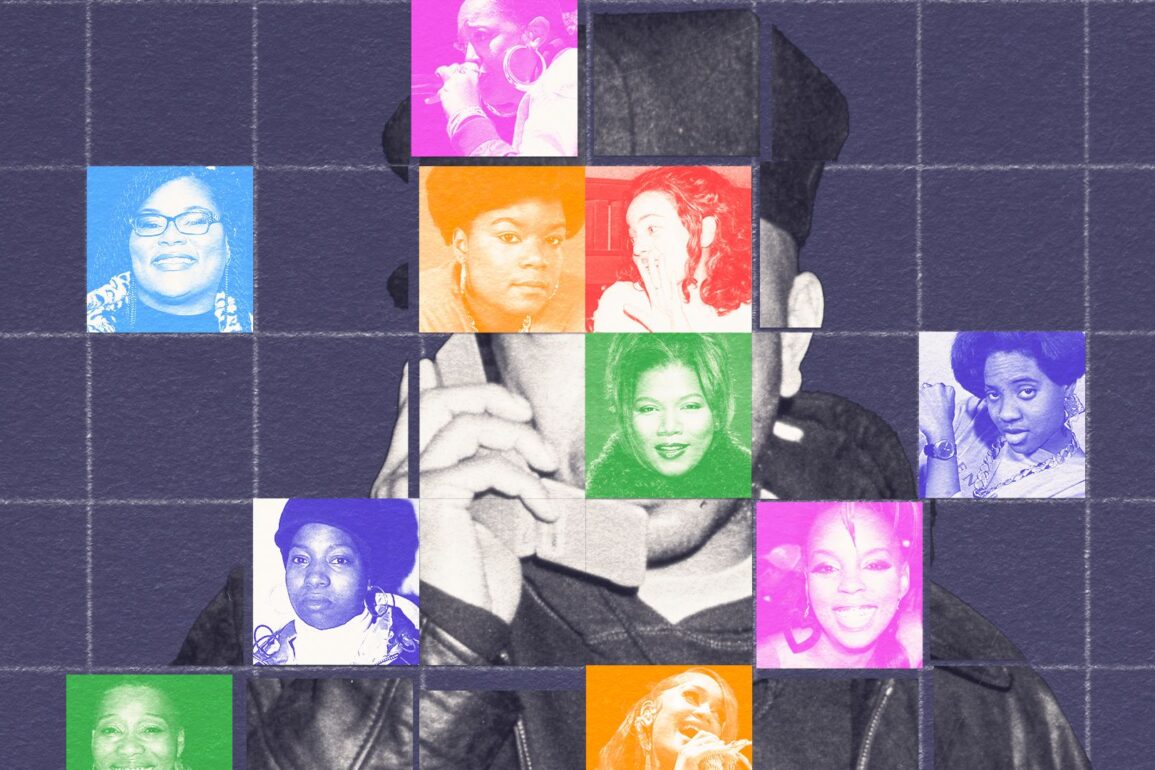

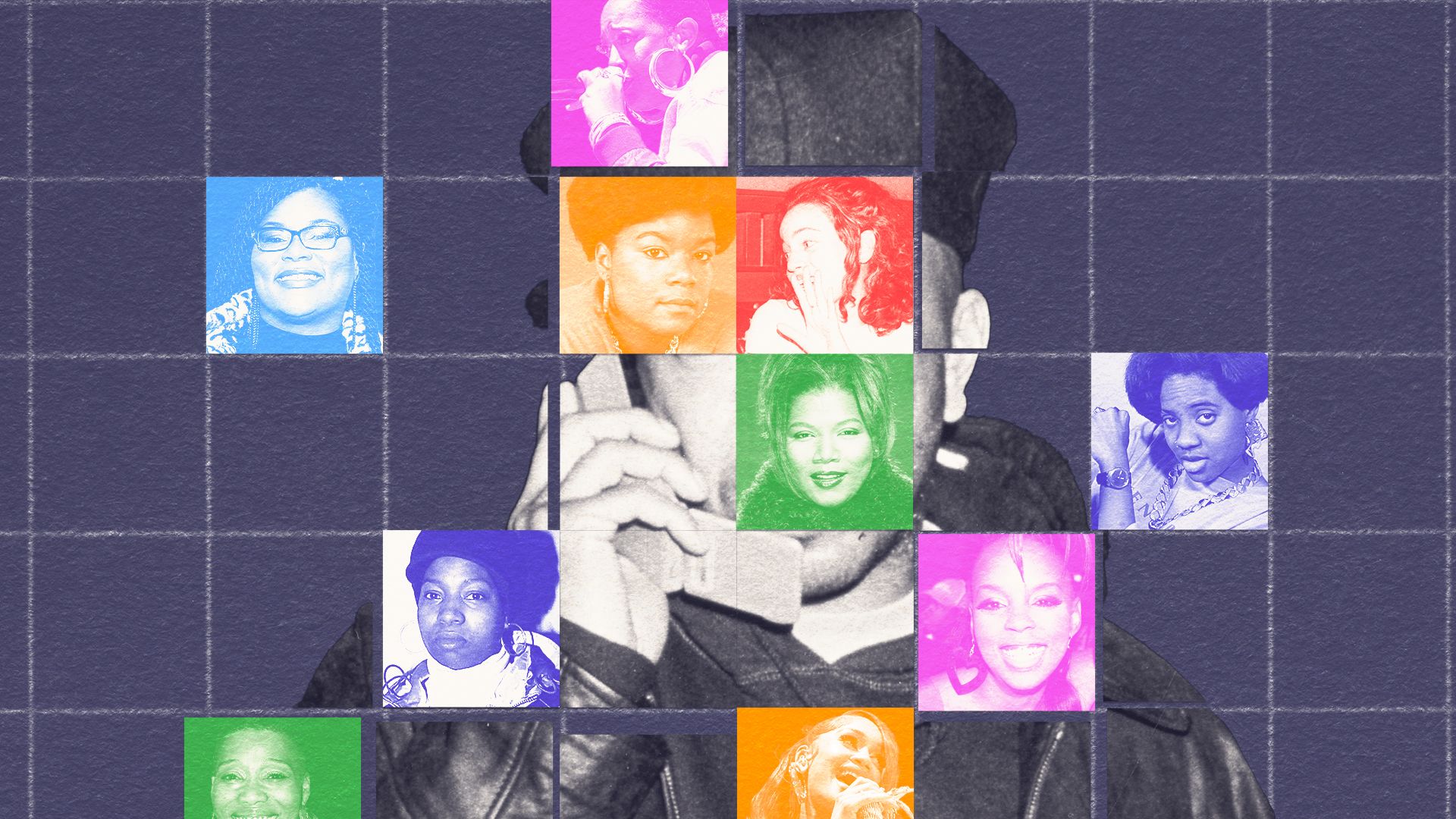

My personal ambivalence notwithstanding, it is glorious to see hip-hop’s unsung pioneers receiving their well-deserved flowers, especially as rap giants like DMX, Plug Two and BizMarkie have fallen too soon. Amid the primarily male-dominated tributes, I have also been pleasantly surprised by the inclusion of women in this moment by a few thoughtful curators, intellectuals and artists. One particular instance brought me to tears. “Ladies First,” a four-part documentary series on Netflix, highlights the contribution of women in hip-hop with palpable affection and unflinching honesty. In the third episode of the series, in which I am honored to appear, executive producer and director, dream hampton addresses the harm and erasure many women in the culture have endured. The gut-wrenching story of trailblazing journalist Dee Barnes, who was violently and publicly assaulted by Dr. Dre in 1991, leaving Dee with lifelong physical injuries and effectively ending her career, is an especially damning account.

With courage and care, “Ladies First” creates space for Dee, Rapsody, Kash Doll, Bahamadia, Misa Hylton and so many other non-cis-hetero hip-hop heroes, pushing us to reflect on the many co-architects of hip-hop whose stories have been overlooked. The series’ fearless energy and electric production felt more quintessentially hip-hop than most rap music I’ve heard in the last 20 years.

Indeed, some of the most compelling voices in hip-hop today belong to filmmakers like dream hampton and journalists like Shanita Hubbard, Kellee Terrell, Soraya McDonald, Janell Hobson, Justin Tinsley, Taylor Crumpton and David T. Dennis. Perhaps the fresh new perspective desperately needed to propel the culture forward may come from a music critic, not a musician. If the first 50 years of hip-hop have taught us one thing, it’s that anyone with a fresh lyric can pick up the microphone or a pen and move the crowd. So I have faith that a dope intellectual or emcee is ready to drop a brilliant verse respecting women, but we must care enough to find him. I do not doubt that a genius with a notebook full of ill rhymes or reflections could spark the seed for hip-hop’s next great love song, but someone in a position of power has to give her a shot.

The misogyny in hip-hop is crushing, but in 1973, when Cindy Campbell and her big brother DJ Kool Herc threw the party that started hip-hop, the Bronx was crushing, too. So surely this culture that has already blown past every expectation, demonstrating its capacity to change the world, also has the capacity to transform itself to embrace women with respect, reciprocity and love.

*The acapella interlude was later replaced on the album with a song called “All I Need,” which was produced and added after both versions of the duet were recorded (both the Puffy and the RZA mixes) so that the new song inspired by my idea could be described, after the fact, as a remix by referring to a track on the album.

This story is part of a HuffPost series celebrating the 50th anniversary of hip-hop. See all of our coverage here.