A former NCAA national champion with a PhD in the history of sport, Victoria Jackson is well suited to speak on the subject, something she does often in the media and at Arizona State University, where she is a clinical associate professor in the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies.

On Sept. 6, Jackson will continue doing what she does best when she gives opening remarks for a public hearing: The Future of Olympic and Paralympic Sports in America.

ASU Clinical Associate Professor Victoria Jackson

Download Full Image

The hearing, held by the Commission on the State of U.S. Olympics and Paralympics, will hear witnesses from across the movement, including more than 11 million Americans participating in youth and grassroots sports at all levels.

During her opening remarks, Jackson will share a historical view on the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic movement. Following her remarks, other key members of the sports industry will discuss topics including:

-

Governance and accountability.

-

Protecting the safety of participants.

-

Athletes’ rights, equity and accessibility, and ensuring fair play.

-

How to build a better future for sports in America.

C-SPAN will begin broadcasting the hearing at 6 a.m. Arizona time.

ASU News talked to Jackson about how history can keep sports accountable ahead of the commission’s public hearing.

Question: How can history help keep sports and the future of sports accountable?

Answer: I believe strongly that any policy team should have a historian at the table. Historians’ jam is contexts and complexities, and an essential part of the job of policymaking is to foresee and nip in the bud “unanticipated consequences.” Historians know how to look at a complex institution of the past and explain how and why it developed and the individual decision-making and broader forces influencing that development over time. A knowledge of history helps us understand the present and build a better future.

Q: Why is providing historical context vital to setting the stage for the hearing?

A: I have been asked to set the stage for the day by providing a sweeping, 10,000-foot historical overview of the past half-century of the American sports ecosystem. The commission will then hear from various stakeholders in the Olympics, Paralympics and grassroots sports. I will be showing, through history, the evolution of the system, recent reforms, and how this system does and does not operate the way it is intended to under the law. The historical analysis I provide will not only set the stage for the day, but it will also set the stakes.

Q: As a sports historian, what does it mean personally that you are being asked to speak and provide that historical context?

A: My goodness, I am so grateful for this opportunity. My work sits at the intersection of Olympic sports, college football, women’s intercollegiate athletics and big-time college sports, and it also positions the U.S. approach to sport within a global context. Making connections among institutions and factors often considered individually and independently of the others — looking holistically at the American sports ecosystem — is more valuable than playing whack-a-mole and treating the various parts of our sports industries as if they are not interrelated. That the commission has asked me to speak in this manner tells me they want to take on a bold, ambitious project, too.

I also care deeply about building a society where sports are for all. I want sports to be fully inclusive, equitable and accessible for all Americans (for everyone everywhere, but in this context, we are talking about U.S. sports) because I know that sports can be personally transformative and can serve communities in ways to help everyone thrive and to bring people from all backgrounds together. I believe in the power of sport. Speaking at this hearing matters a whole lot to me.

Q: Congress created the commission to seek better oversight of the Olympics and Paralympics in this country. What can you share about the topics discussed throughout the hearing?

A: One focal point will be an evaluation of the USOPC’s execution of its dual mandate from Congress to serve both the apex of the sports pyramid — Olympic and Paralympic development — and the massive grassroots base. I look forward to hearing from grassroots sports experts, including Tom Farrey and Dr. Vincent Minjares from the Aspen Institute’s Sports and Society Initiative and Project Play. Their work on youth and grassroots sports is a game changer.

Another topic, and a primary reason for creating the commission, is athlete health, well-being, safety and protection from abuse. Grace French, the founder and director of The Army of Survivors, Donald Fehr, who has served as executive director of players’ associations in the NHL and MLB, and others will testify about athletes’ rights and protections.

Q: What is the importance of these hearings to help move forward the future of sports in America, especially the Olympics and Paralympics? What does this mean for supporting athletes?

A: The American sports ecosystem is at a crossroads. Business practices in some sectors have been irresponsible and unsustainable to a breaking point. Barriers to access we see in other elements of society are very much present in grassroots sports, making access to sports teams too often a product of privilege. Though intercollegiate athletics is not part directly of the American Olympic and Paralympic Movement, Olympic development happens within American higher education, and recent events show that significant changes to the design of big-time college sports are likely on the horizon. We have the best sports infrastructure in the world, thanks to our schools, and more — all — Americans should have access to sporting spaces, not just as spectators but as participants, too.

I will not be making policy recommendations at the hearing. But I do have lots of policy ideas. I would like to see an overhaul and redesign of the American sports ecosystem. I want to see an independent body, perhaps a sports ministry, that serves as a hard backstop of regulation, coordination, transparency and accountability through checks on power, something the American sports ecosystem does not have.

The impressive people on this commission know what they are doing and will be putting brilliant policy recommendations before Congress in a convincing way. I am honored to play a small part in this critical work.

Mitchell Jackson says fashion choices have become competition among players

Mitchell Jackson has been an NBA fan for as long as he can remember.

He grew up in Portland and was born one year before the Trail Blazers won their one and only NBA championship in 1977.

“As a Portlander, it’s a special relationship because while I was there, they were our only major sports team,” said Jackson, a Pulitzer Prize winner and the John O. Whiteman Dean’s Distinguished Professor in Arizona State University’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “So the Blazers really meant something to us.”

So when the idea of writing a book about NBA fashion was broached to him, he was immediately interested.

“They brought the idea to me knowing that I was already a basketball fan and that I love fashion,” Jackson said. “It just seemed like an east fit. They pitched it as a really short, almost inconsequential book that would take a couple of weeks of my time. It turned out to be years and lot more effort than I anticipated.”

That result of that effort? “Fly: The Big Book Of Basketball Fashion,” a photo-heavy coffee table book that will be released Sept. 5.

MORE: New York Times book review

ASU News talked to Jackson about the book.

Editor’s note: The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Question: How would you describe the book?

Answer: I would say that it is a chronicle of NBA fashion, but as much as it is that, it’s also a kind of cultural capsule for the ways in which history and culture shape fashion, and then vice versa.

Q: You write in the book that the hip-hop culture heavily influenced the way NBA players think of fashion. In what way?

A: Hip-hop is Black and brown fashion, right? It was born in the Bronx. Everybody knows the story. So for as long as hip-hop has been around, the purveyors and the people who define what hip-hop is have always been Black and brown people from disenfranchised neighborhoods. And those are the same people who comprise the NBA. We’re really talking a cultural thing. So that influence goes back and forth, but really, it’s the same neighborhood dudes influencing each other.

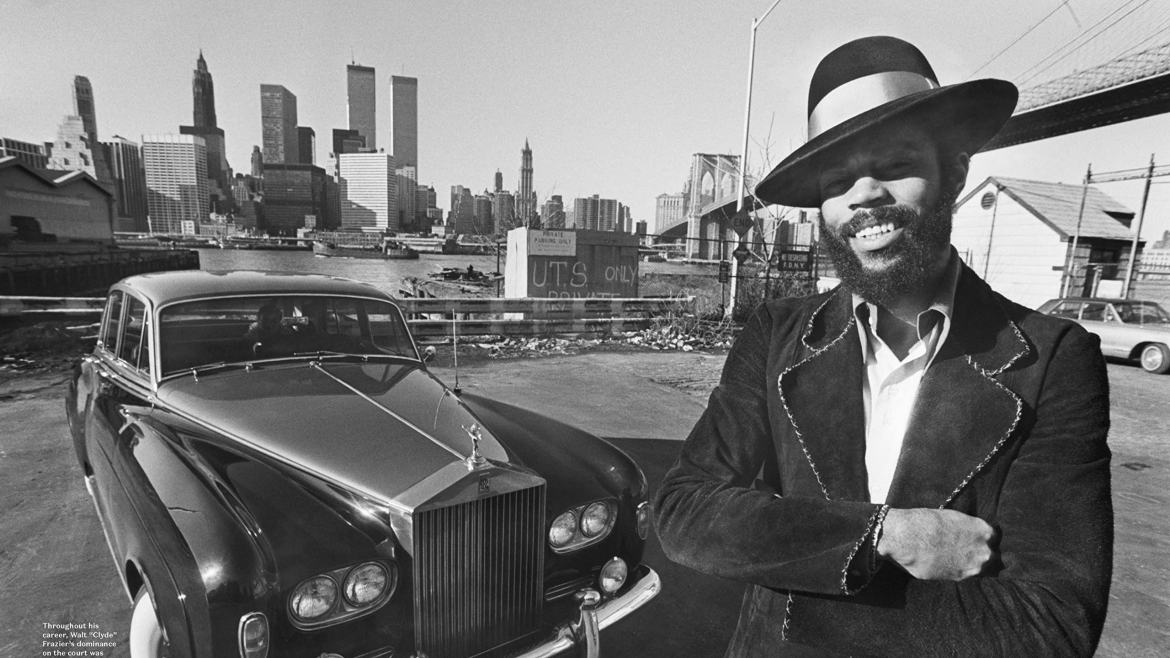

Q: You had Black players in the past who really showed off their fashion choices, like Walt Frazier and Julius Erving, but it seems to be almost an industry now for NBA players. What changed?

A: The platform. They (players in the 1970s and 1980s) didn’t have social media. If you happen to see those photos of Dr. J and Walt Frazier in the book, those are posed shots by professional photographers. A lot had to go into the casual fan being able to see those. Now, a player can create that kind of moment for themselves all day, whenever they want. I also think the embracing of fashion by brands didn’t exist back then.

So just the avenues for social media, the brand collaborations and — as we talked about the connection between sports and fashion — hip-hop kind of paved the way for making yourself into a brand. And I think that the NBA, which is the smartest professional league in terms of marketing their players, was very savvy in allowing their players to demonstrate their individualism in this way.

Q: You mentioned social media. How big of a factor has Instagram played in NBA fashion?

A: It’s really become its own cottage industry. There are so many websites or handles dedicated to just posting what the players are wearing. It really has become corporatized in a way. The critique could be that this is just late-stage capitalism. Designers are seeking out players to wear their clothes. I don’t know how much they get paid, though.

Q: Among NBA players is there a competition as to who looks the best?

A: Absolutely. These guys are all competitors. If you see those documentaries of Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant, they wanted to win at everything. I don’t hang out with NBA players anymore, but I’m sure it’s, how many cars and what kind of cars do you have? Or how big is your house? So they’re finding ways to delineate themselves. I think the difference between today’s players and players in the past is that you can actually be a star in fashion and never become a star on the court. The guys you mentioned, like Walt Frazier and Julius Erving, were NBA stars. Now you can be a guy who basically never gets off the bench but everybody knows you because of your fashion.

Q: Because of social media, right?

A: Yeah, but not just social media. You can have relationships with brands. We become aware of these players usually through social media, but then all these other avenues open up, where they’re in commercials or doing other things and becoming a brand themselves.

Q: Are more players using fashion to make political statements than we’ve seen in the past?

A: No question. When Black Lives Matter began as a national movement, players were wearing Eric Garner T-shirts and Trayvon Martin hoodies. I think maybe one of the first viral moments was LeBron James and the Miami Heat wearing those Trayvon hoodies. So, yeah.

Q: Former NBA commissioner David Stern instituted a dress code in 2005 that barred, among other things, players wearing T-shirts and shorts to games. There was a lot of resentment among players back then, but in retrospect, did that sort of ignite the NBA fashion industry?

A: Yes, because they had to wear dress clothes, and in dress clothes, you couldn’t express your individuality that was connected directly to the culture. So you had to be creative and figure it out. And I think that pointed the stars toward high-end brands. So now you’re wearing the high-end European brands and they’re hiring stylists, and sooner or later they end up at a fashion show. So I think Stern pointed them in a direction that created what we have now, even though I think it was punitive against the culture.

Q: This may be an impossible question to answer, but I have to ask it. Who do you think is the best-dressed player in the NBA?

A: I don’t know if I have a favorite, but I have different styles. For a Bohemian-kind-of-chic player, I like Jerami Grant of the Trail Blazers. If you said, “What does a rich basketball player look like?” that’s LeBron James. That’s everything from his jewelry to his clothes. He always has on a bunch of bracelets or earrings. He always wears the richest clothes, as he should, right? I mean, he’s the game’s first active billionaire. So I would say those two players.

And, if you’re talking streetwear, I would say (former Phoenix Suns player) P.J. Tucker. He’s not only a really great representative of streetwear fashion, but he is also a representative of the way in which your fashion can give you a certain cachet that your play doesn’t. He’s a starter, and he was on an NBA championship team (with the Milwaukee Bucks in 2021) but no one is running around saying P.J. Tucker is an NBA star. But he is in the fashion world.

Upcoming events:

7–8:30 p.m., Thursday, Sept. 14

ASU California Center Broadway

Mitchell S. Jackson in Conversation with Marc J. Spears

7–8:30 p.m., Sunday, Oct. 15

Phoenix Art Museum

Top photo: Walt “Clyde” Frazier, who was with the New York Knicks from 1967–77, photographed on the Brooklyn waterfront with his Rolls-Royce in 1973. From the book “Fly,” courtesy Artisan Books

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.