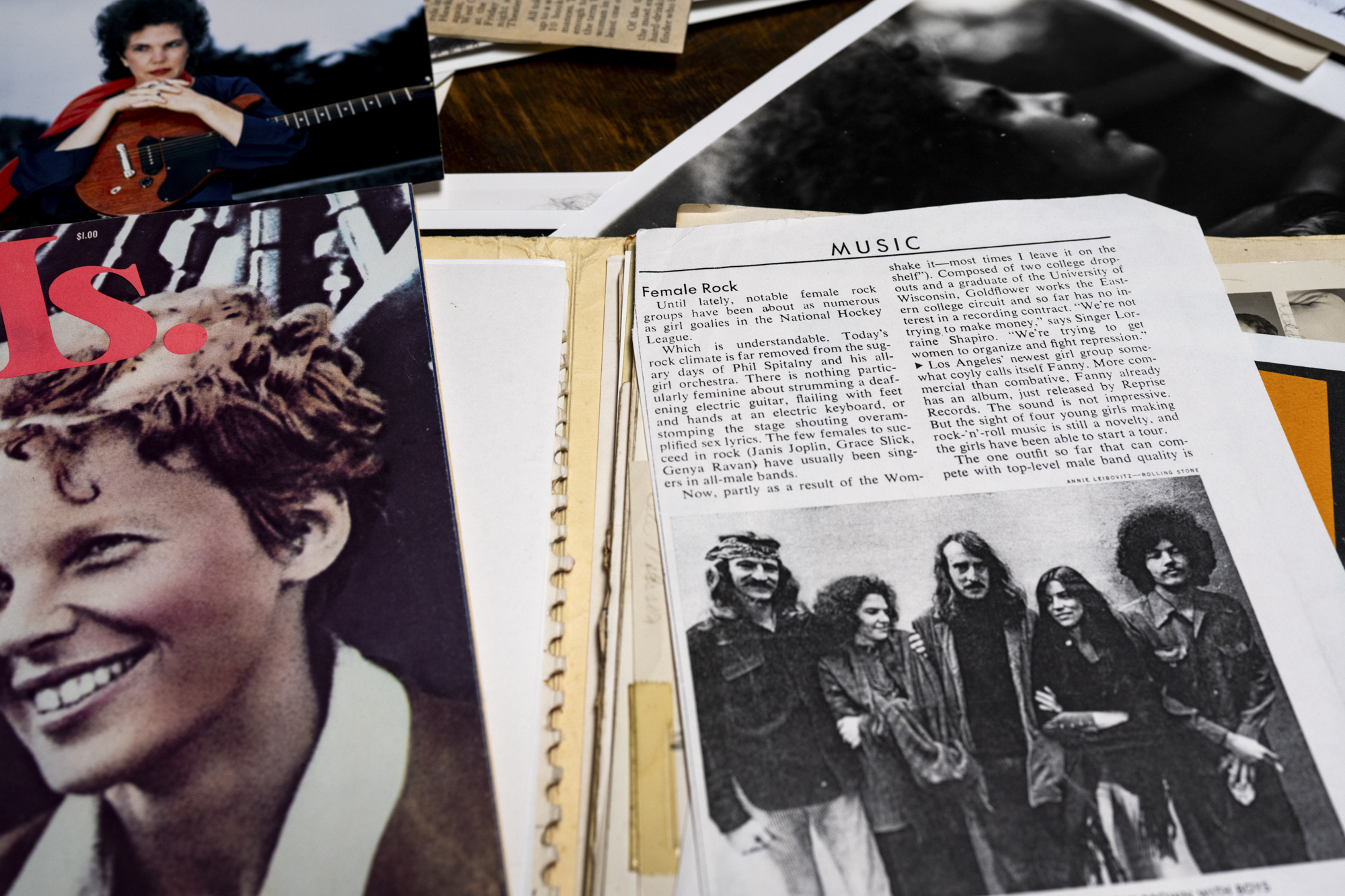

Her Gibson six-string guitar is propped next to her, near a hand-painted marimba and a binder of news clippings about her music, including an Annie Leibovitz photo of Joy of Cooking. The 1979 edition of The Rolling Stone Record Guide sits alongside Garthwaite’s self-published song books, like Verbal Remedies: Songs to Soothe the Spirit. Crystals line the windowsills. Two diplomas advertise Garthwaite’s bachelor’s in sociology from UC Berkeley (1965) and her certification from Joy Gardner-Gordon’s Vibrational Healing Program (2001). Only the latter is framed.

“So,” she says. “You wanted to ask me some questions?”

The tough rock singer

Terry Garthwaite’s first love was the blues. A true child of Berkeley — her grandfather was a sea captain who settled in North Berkeley, and all her aunts and uncles lived nearby — Garthwaite grew up at the corner of Scenic and Vine, in a house where she and her two brothers’ creativity was encouraged. Their father was an illustrator who also played violin, self-published poetry books and belonged to the Bohemian Club; their mother was a dancer and ballet teacher. They gave their daughter her first guitar, a Martin acoustic six-string, when she was 14.

She was drawn to bluesmen like Leadbelly, Blind Willie Johnson, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. Pops Staples from the Staple Singers was especially influential in her guitar playing, says Garthwaite. “And I still think of Mavis Staples as being my mentor. I never met her, but I just loved her style.”

While she completed her degree at Cal, the clubs and coffeehouses of ’60s Berkeley provided the rest of Garthwaite’s education. She met singer-songwriter Toni Brown at a house party in 1967: Brown sat down to play the piano, Garthwaite picked up her guitar, and the alchemy was instantaneous. “I liked her writing and she liked my singing,” says Garthwaite. “So we decided to get together and experiment.” They recruited a three-person rhythm section that included Garthwaite’s younger brother, David, on bass.

By 1969, Joy of Cooking had a weekly gig at Mandrake’s, a club at the corner of 10th and University that hosted B.B. King, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and Big Mama Thornton. On stage, Garthwaite and Brown refined their salty-sweet vocal dynamic, performing adventurous songs with driving, danceable rhythms and feminist themes woven subtly throughout the lyrics. For a time, it seemed Joy of Cooking was the house band not just for Mandrake’s but for Berkeley: They were the entertainment at People’s Park on the storied day in 1969 when the neighborhood hippies first came together to plant trees and construct a playground there, kicking off an idyllic few weeks before the University tried to take it back.

Within a year, Bill Graham was booking the band at the Fillmore West and Winterland Ballroom, opening for the likes of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Joy of Cooking also shared stages with the Band, Santana, Pete Seeger, Allen Ginsberg, an early version of Jefferson Airplane (“it was at a little club in San Francisco called the Matrix, we got paid $11”) and Janis Joplin — who reportedly felt competitive with Joy of Cooking.

“I think we were a threat to her. Somebody told me that: that I was a threat to her,” says Garthwaite. “Which I was not. But Joy of Cooking was an up-and-coming band.” She shrugs. “Too much attention.”

That dynamic speaks to the sexism of the time: for women musicians, there really was only a sliver of attention — and money, and festival slots, and airtime — to go around. Garthwaite remembers being on tour after Joy of Cooking released its self-titled debut LP in 1971, and doing a promotional stop at a radio station. “The DJ said, ‘Oh, we already played our limit of women for the day,’” recalls Garthwaite. “There was a quota.”

A 1971 TIME magazine article (headline: “Female Rock”) further illustrates the prevailing attitude of the era. A Detroit group called Pride of Women is described as “four leggy but irate girls” who make music that’s “ferociously antimale.” Of L.A.’s all-female rock band Fanny: “The sound is not impressive. But the sight of four young girls making rock-’n’-roll music is still a novelty, and the girls have been able to start a tour.”

Joy of Cooking fares the best here, with a positive (albeit patronizing) blurb: “The one outfit so far that can compete with top-level male band quality is Joy of Cooking, and it is only partly female,” it reads, describing Garthwaite as “a tough rock singer” and Brown as “a pretty Bennington graduate … [who] writes songs about what it is like to be a woman.”

“It remains to be seen,” the piece concludes, “if the male-dominated world of rock music is really ready for Women’s Lib.”

‘I don’t put myself in a bin’

Garthwaite doesn’t seem bitter about what she experienced in those years: the misogyny, the pigeonholing, the condescension. But there’s no denying that she’s spent the decades since Joy of Cooking disbanded consciously turning away from the commercially oriented, capital-I industry.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.