London

CNN

—

A young, elegantly dressed Black woman wears a small but determined smile on her face. Graffiti on the door next to her reads “KEEP BRITAIN WHITE.” The photograph, taken by Jamaican-born photographer Neil Kenlock and part of a new exhibition at London’s Somerset House, is impossible to look away from.

“The Missing Thread, Untold Stories of Black Fashion” is filled with photos like this, as the showcase dives deep into the history of Black British culture from the 1970s to the present day — specifically, how it has been a forgotten influence on the fashion industry.

“There’s a resilience that has had to be forged in the community,” said Andrew Ibi, one of the exhibition’s curators, of the woman in Kenlock’s photo. “In the face of this, people would expect her to be wearing riot clothes, but she looks immaculate: Her hair’s done, she has jewelry on… It’s like a uniform of resilience.”

It took Ibi, Jason Jules and Harris Elliot — the designers and academics behind the Black Orientated Legacy Development Agency (BOLD) — almost three years to make the show.

“This goes way beyond fashion,” said Jules in an interview with CNN. “Fashion is the trojan horse.”

While the last decade has seen a rise in the number of Black creatives and designers gaining recognition — from Law Roach receiving the first ever Stylist Award at the 2022 CFDA Fashion Awards to Chioma Nnadi becoming the first Black woman to edit British Vogue — Ibi, Jules and Elliot felt there were more stories to tell.

Some are anecdotal experiences. Ibi remembers the disadvantages he faced even as a student, using his loan to buy his mother a gas fire for their freezing house in the winter. “There have always been disparities in our journeys,” he said. “My (White counterparts) were not operating in that way. It came to a point where I thought this can’t all be rotten luck, there is something else stacked against us.”

There are painful recounts of failed fashion careers, such as that of 1990s designer Wayne Pinnock. A fashion graduate from London’s prestigious Royal College of Art, Pinnock’s early work was spotlighted by legendary style journalist Suzy Menkes in the New York Times, and he even spent time working for Moschino in Milan. Despite such promise, the exhibition chronicles, Pinnock works in a supermarket today — his fashion flowers withheld, until now.

Others stories featured in the exhibition come from the historically ignored perspective of Black women, though Jules admits they were hard to locate. “We realized how much Black women were missing from the conversation. It wasn’t enough to have Black women in photographs. We wanted photographers, creatives, designers,” he said. “We struggled to find many. Where were they? Is it because they don’t exist? Were they not good enough? It comes down to many of them now having their story told in the first place.”

It’s a common theme — a missing thread that unites the exhibition together. Voices erased from history, now exhibited pride of place. Elliot found his role as co-curator particularly emotional — unearthing, researching and frequently revisiting decades-old experiences of racism. “Charlie Allen (a third generation Black tailor) told me that at one point whilst he was working at an establishment on London’s Regent Street in the 1990s that the racism was so bad, he had to recite the 23rd Psalm when he got into the lift every morning because it was the only thing that got him through the day.

The show is about connecting the dots — whether that be through a nail bar installation that nods to the influence of nail art, prevalent in dancehall fashion and now widely co-opted by White celebrities and popular culture; or mapping the influence of trailblazing designers such as Bruce Oldfield (one of the royal families favorite couturiers and designer of Queen Camilla’s coronation gown) or Ozwald Boateng (the first Black man to work in London’s esteemed tailoring institution Savile Row).

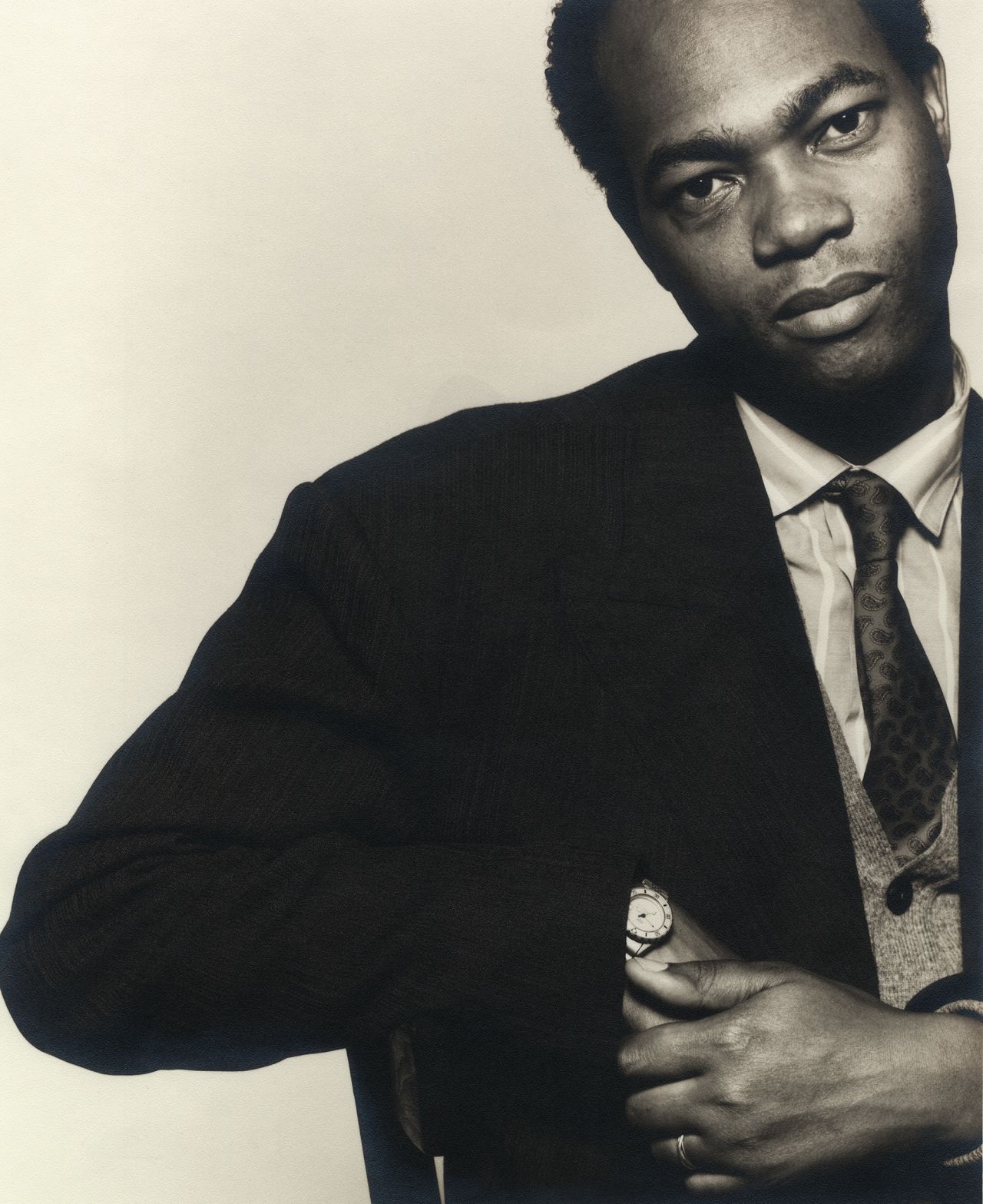

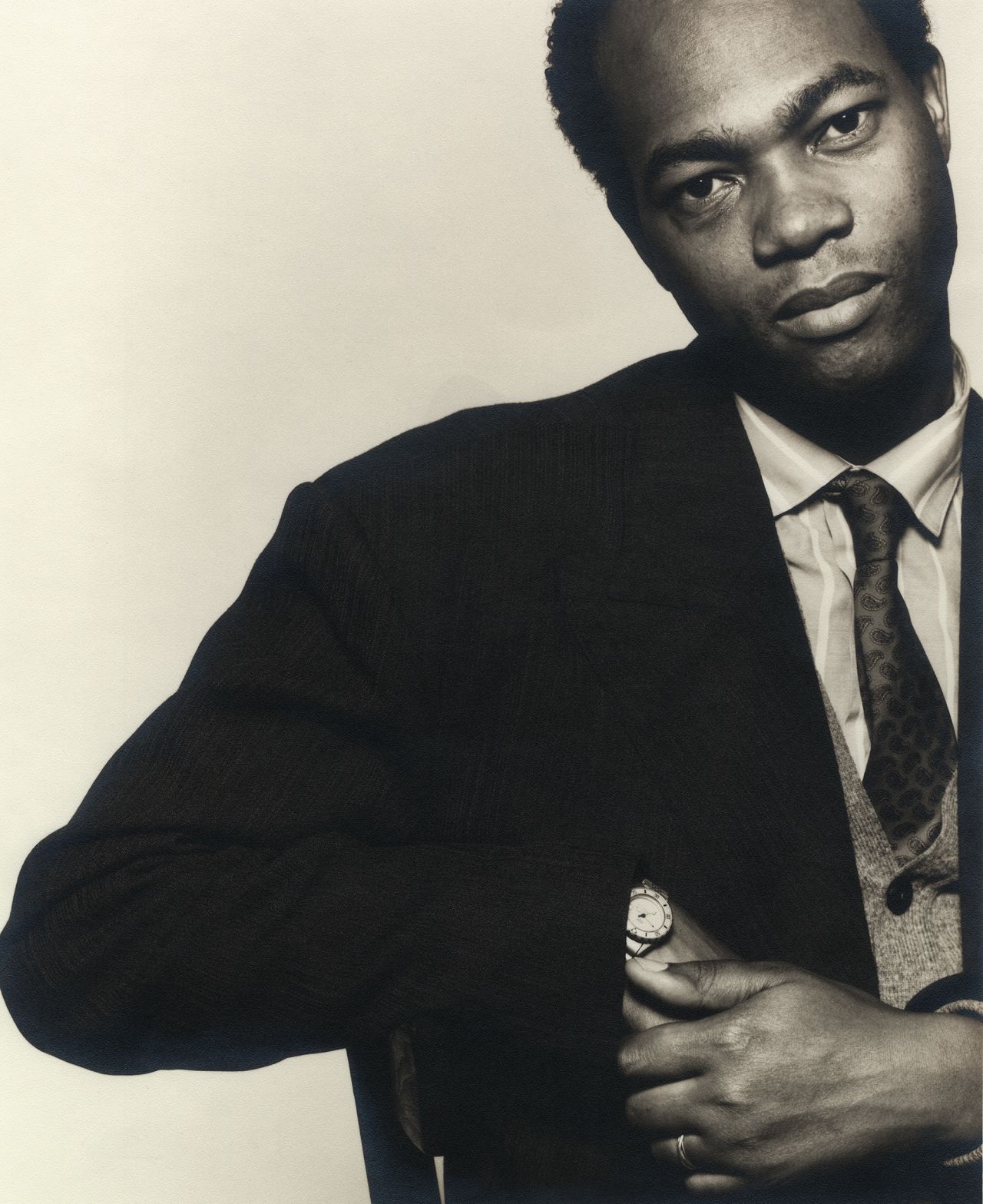

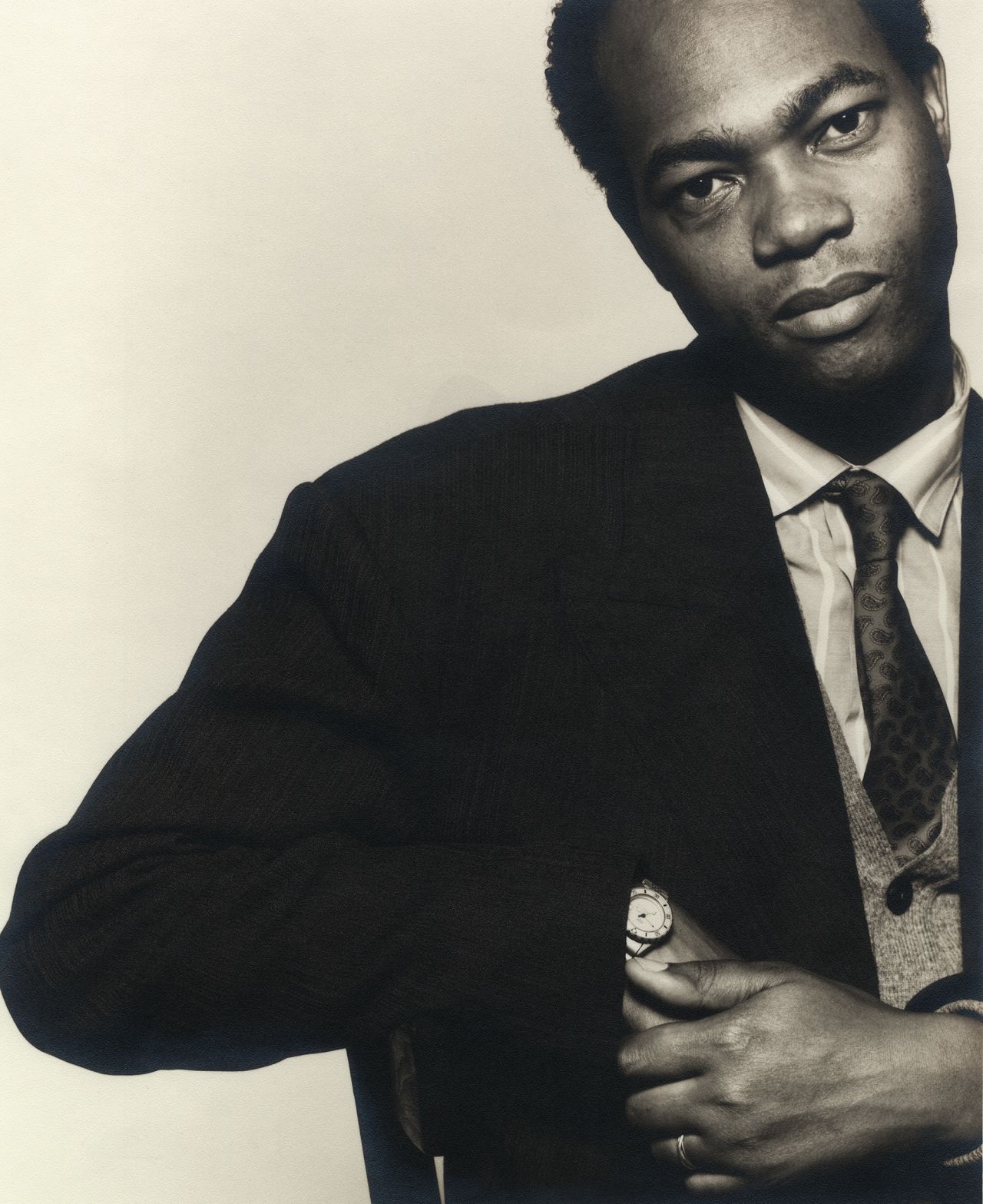

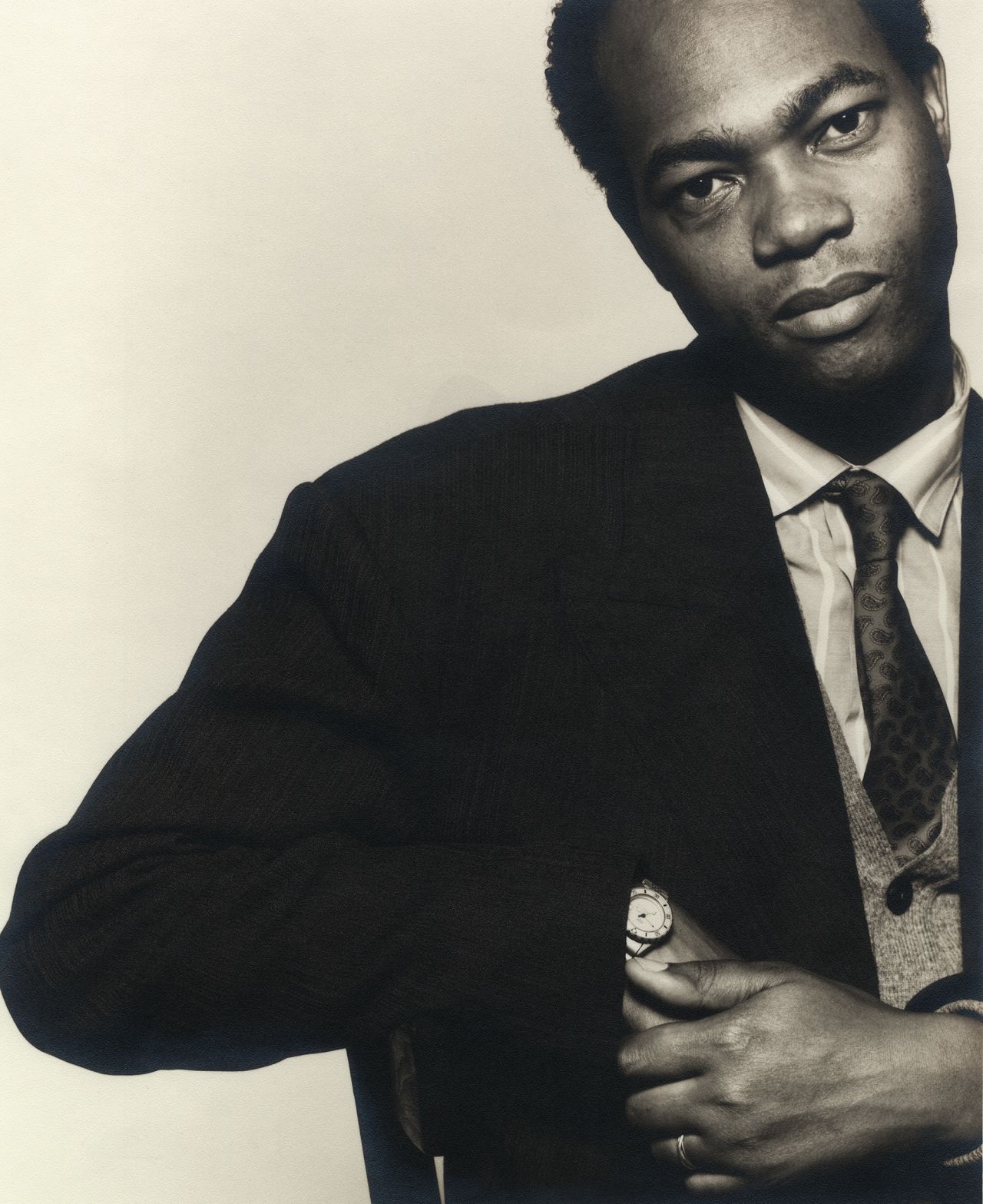

At the center of the exhibition is the work of Black British designer Joe Casely-Hayford, who died in 2019. Casely-Hayford was nominated for Womenswear British Designer of the Year in 1989 and also Innovative Designer of the Year in 1991. While his clothes are part of history (U2 singer Bono wore his designs when he became the first man to appear on the cover of US Vogue in 1992) his name has long stood adjacent.

In 2007, Casely-Hayford received a Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE) for his contributions to the arts, and his pieces are now part of permanent collections at the Victoria & Abert Museum in London and the FIT Museum in New York City. “The Missing Thread” is, however, the first ever major showing from the designer’s archive.

“I remember speaking to Charlie (Joe Casely-Hayford’s son) who had tears in his eyes when he told me that he didn’t think his father’s story was ever going to be told,” said Harris. “How do you turn some of that pain into something, yes, challenging, but also something of beauty? While I’d love people to leave with a little more of an understanding of what our experiences as Black designers have been, amidst all that, I would love people to see and acknowledge the beauty in what we do.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.