Want to look your best? A beauty box, new on the market, offers instant improvements: brow shaper, eyeliner, cheek enhancer, a pair of padded falsies in frothy white lace, plus the full range of available beauty spots. These are shaped like moons, stars or flirty hearts, and can be positioned on the face to indicate degrees of availability, character and even politics. A black spot on the right cheek, near the nose, and you’re an inveterate Tory.

The spots in this 19th-century box were made of black silk, unlike the original mouse fur patches, worn by men as well as women across Europe from the 1640s onwards. The fashion for covering your blemishes with “mouches” began to fade with the discovery of a smallpox vaccine in 1796. But you can still buy beauty spots today. It seems they never go out of style.

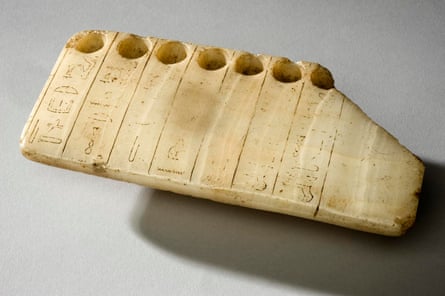

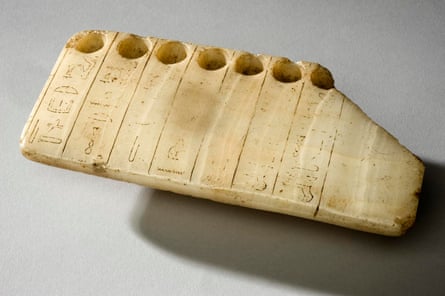

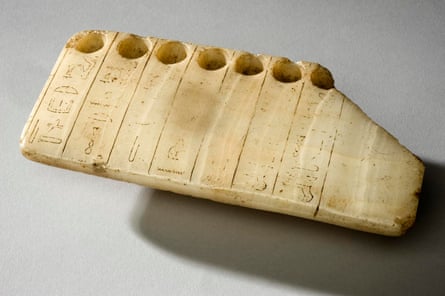

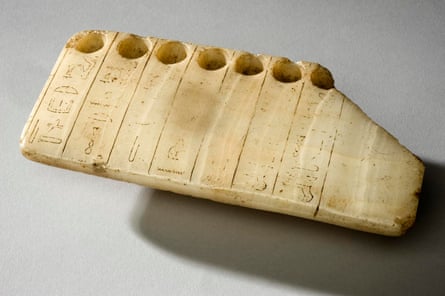

That is not the least revelation of The Cult of Beauty, a terrific show of more than 200 objects and artworks at the Wellcome Collection. The desire for beauty never changes, and never abates. The first cosmetic palettes here, for grinding and storing coloured eye shadows, go back to Neolithic times, and there are face coolers and fat rollers made entire millennia apart.

A fabulous section on the beauty industry at its most delusional, not to say costly, centres on the use of liquid gold. A lithograph of Diane de Poitiers shows the 16th-century French courtier in her boudoir, where she used to drink “aurum potabile” to preserve her youth and beauty. Scientific examination of her hair suggests it might have killed her. Right next to it is a facial serum of pure gold and peptides from 2023.

The exhibition maintains a fine balance between beauty – standards, ideals – and how to achieve it. The first sculpture you see is that of the ancient Egyptian Nefertiti, with her exquisite swan’s neck and heavily kohled brows and eyes. The Wellcome’s own Black Madonna follows – a much-revered 17th-century painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe. And the Hindu deity Krishna, his name meaning black or dark blue, to match his appearance, appears in a coloured print captivating some Indian girls with his knockout beauty.

Indeed, the show hurtles fast through western notions of beauty, from a statue of Venus to sultry Hollywood starlets and Vogue cover girls. This is partly, and importantly, to speak to different races and ideals. A neoclassical statue of a hermaphrodite is deliberately opposed to the depilated Venus. There is a superb gallery of androgynous beauty in life and art. JD ’Okhai Ojeikere’s exquisite photographs of modern hairstyles in Nigeria make every European perm in the show look feeble.

But it is also because the curators have a keen sense of the ludicrous. So much so that one of the show’s principal stars is William Hogarth, forever sending up towering wigs, wasp-waisted corsets and impossible symmetries (even in the anatomical drawings of Albrecht Dürer, mocked by Hogarth in his irrepressibly satirical print The Analysis of Beauty). Best of all, though, is a scaled-up lifesize mannequin of Barbie, made by Adel Rootstein Ltd for a German museum. With a 21-inch waist, hips scarcely any larger and legs too spindly to support them, she is fully as ridiculous as expected.

The extremes of the industry itself are, of course, yet more enthralling. A photograph of Helena Rubinstein, surrounded by white coats in her beauty “laboratory”, might have looked advanced in 1950s America. But snake-oil salesmen have always tried to come over as doctors. What startles is just how many aesthetic procedures have their origins in actual medicine.

Electrotherapy for wrinkles and sagging necks was first used to treat tuberculosis. The oxygen therapy beloved of Hollywood stars was originally a treatment for asthma. Face masks fitted with LED lights that are supposed to improve everything from undereye bags and rosacea to that inconvenient little breakout were first used by Nasa to promote wound-healing in astronauts.

This is exactly the kind of knowledge you would hope for from the Wellcome Collection. And the museum doesn’t hold back on its own association with the beauty racket either. In the late 1890s, the pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome & Co began producing Hazeline products. Most popular of all was a skin cream called Hazeline Snow. Certain eBay traders are still selling it today with the explicit use of the word “whitening”.

The belief that light skin is more beautiful than dark goes entirely with colonisation; or so it may seem. The writer and broadcaster Emma Dabiri, one of several historians selecting special objects for this show, points out that this theory is not so simple. She includes a beautiful illustrated recipe for Chinese pearl powder lightener made in 1591, predating western notions of superiority.

Who dictates how we should look? Take a friend, if you’re going, for the ceaseless discussion. Early on, it seems as if men are in charge. One of the most revolting exhibits is a 17th-century print of husbands taking their old/ugly wives to a windmill to be “improved” through grinding. And there are other misogynistic images lampooning older women for keeping up appearances when they obviously ought to give up.

But just as horrifying is a real object, a buckled maternity corset (designed by a woman) from the Mad Men 50s. And what to make of Saint Rose of Lima, who tried to destroy her own looks by rubbing peppercorns into her face until it blistered, because only Christ could be beautiful? And what about the dandy’s steel corset or, reductio ad absurdum, the teacup with inbuilt protector for keeping your fashionable beard dry?

Once so constricted, ideas of beauty are growing more expansive. Since 2012, the Brazilian artist Angélica Dass has been photographing people of all ages and races, matching pixels from the nose of each subject to a Pantone colour that forms the background. Her camera is so attentive, the uniqueness of each being so graciously emphasised, that every face is as beautiful to the eye as the human race should be.

And how glorious, too, is the ever-expanding Pantone range. This is surely the essence of the singer Rihanna’s colossal success with Fenty Beauty, with its 59 shades of matt foundation and counting.

This riveting exhibition ends with the full shock of a facelift, however, as recorded by the photographer Zed Nelson. A woman lies on a hospital bed. The whole of her face appears flayed from her head by the surgeon’s scalpel: an envelope of skin he treats like a mask. Why would anyone do this? Why would you bend, break, falsify, conceal, reshape or spend your hard-worn earnings in the pursuit of beauty? This question is at the heart of the show – along with the industry’s sly answer: because you’re worth it.