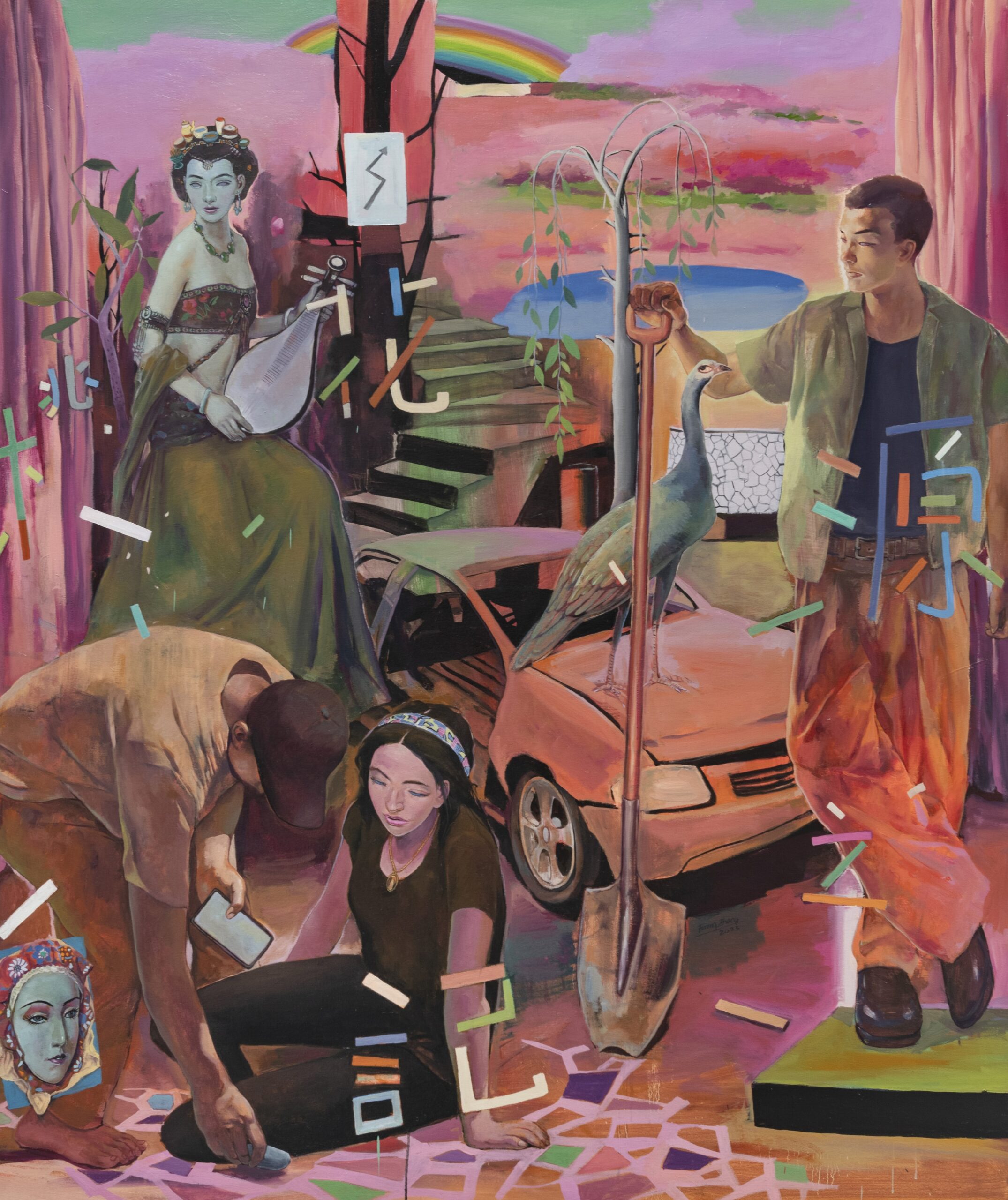

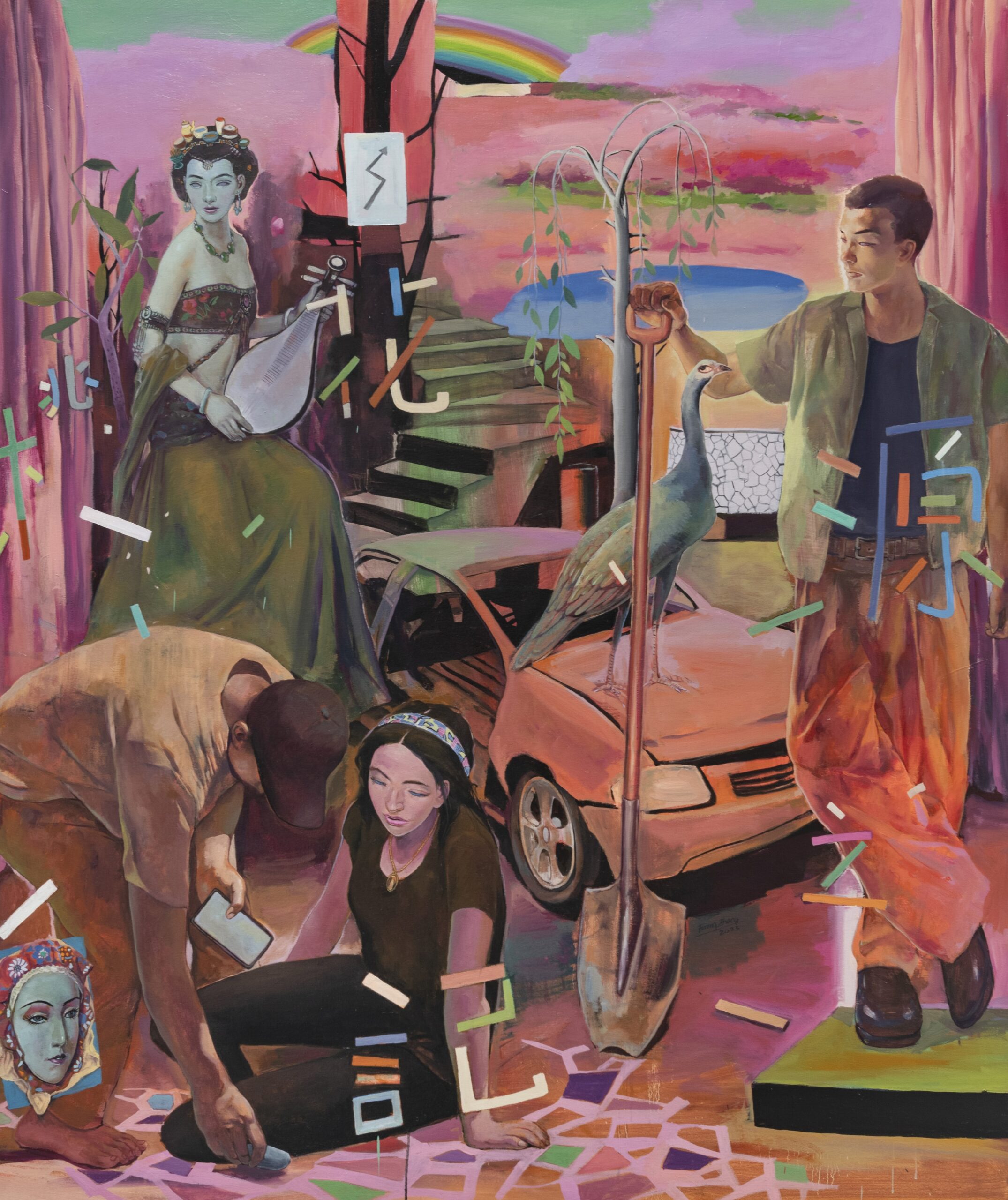

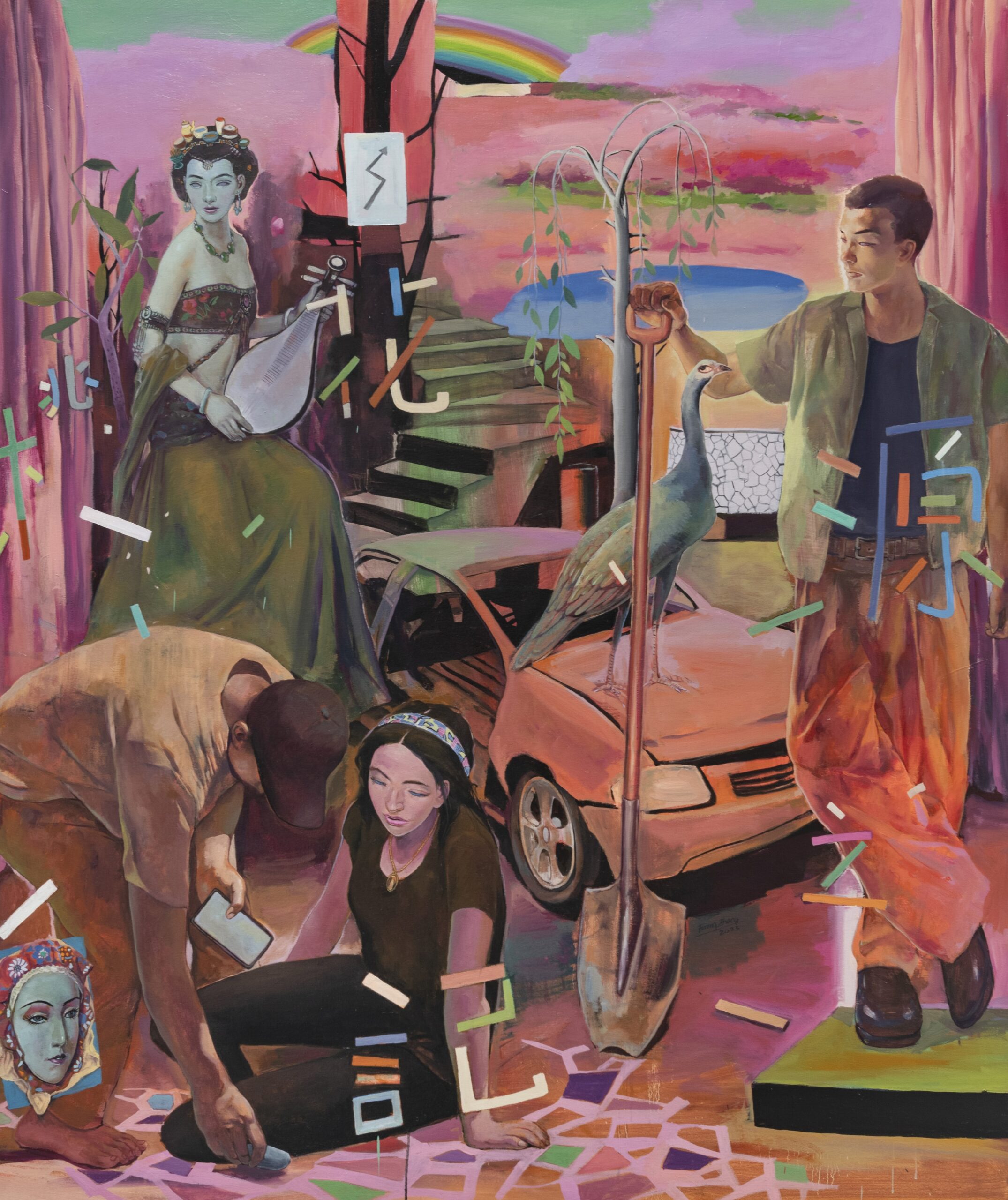

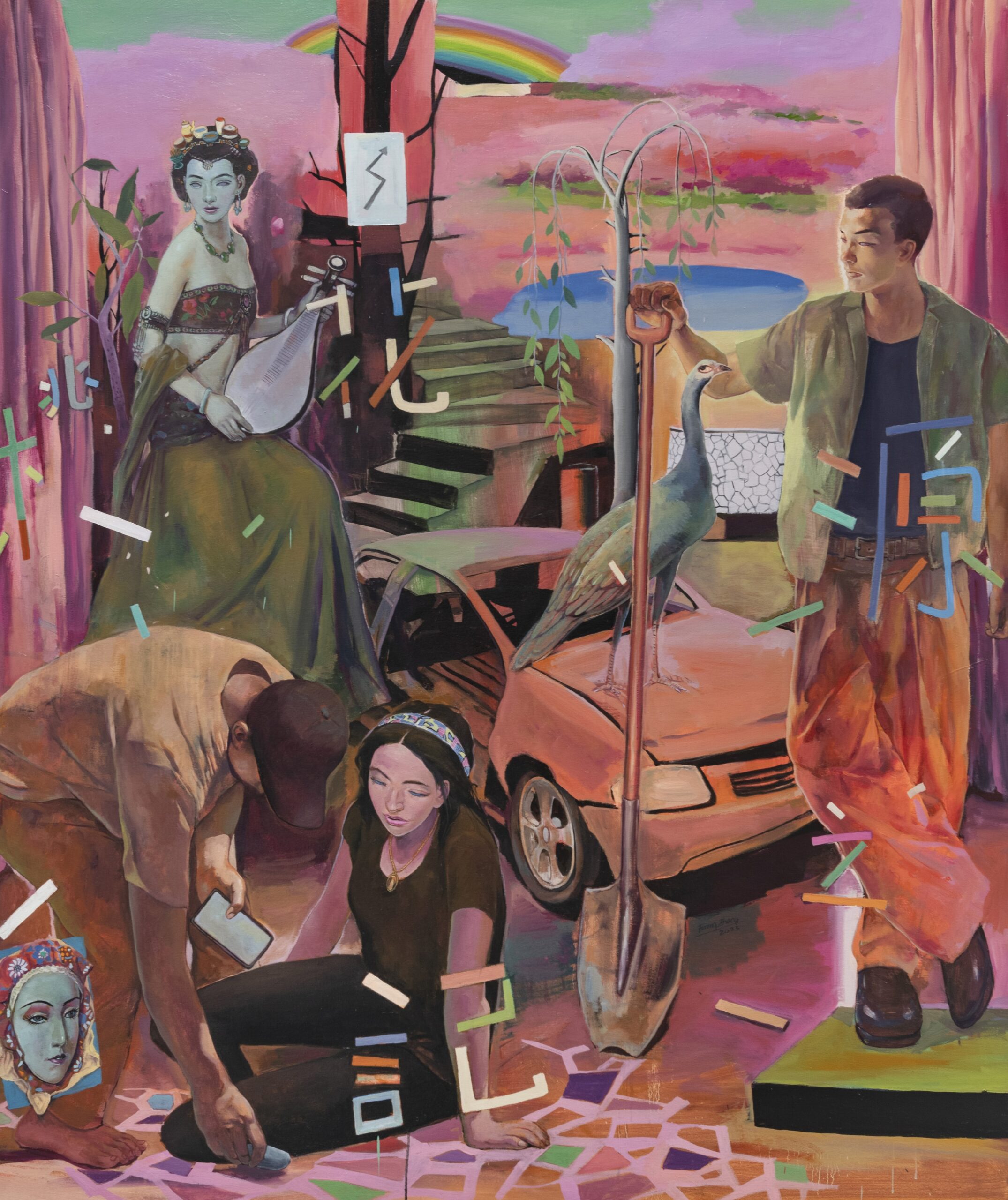

How does a Chinese tale from more than fifteen centuries ago connect with the experience of a first-generation Asian American migrant in the United States? In “Land of the Peach Blossoms,” now at Kravets Wehby Gallery, Shanghai-born artist Furong Zhang convokes ancestral and folk memories to invent an iconography of loss, displacement and heritage.

Zhang’s new figurative paintings depict an introspective world caught between realism and surrealism, where the boundaries of dream and nightmare, utopia and dystopia blend and blur. His works in the solo exhibition are mainly large-scale and multi-character in nature—except for two portraits—and they alternate between intensely cold and sizzling warm color palettes, featuring a cast of ageless, theatrical individuals who engage with uprootedness and belonging.

We find traces of mythological pasts and touches of contemporary visual culture in these vignettes. For instance, he incorporates the ancient Chinese garden philosophy in Small Fires (2023), a zodiac wheel in Marionettes and Masks (2023) and various spectral figures who seem to vanish in viridian, teal and desaturated hues, creating dissonant, compositionally disjointed scenes of post-human decay where various realms co-exist at once.

In Red Stage (2023), Zhang depicts four female characters in an urban landscape reminiscent of New York, where Zhang lived for nearly two decades before moving to central Pennsylvania. Each woman’s outfit represents a slice of China’s vast history—an early 20th century to mid-century qipao, an imperial-era robe, everyday jeans and t-shirt and a more futuristic expression in fashion. Around the women are vestiges and signifiers of capitalism: rusty and worn-down New York City subways (one of the carriages has the word ‘utopia’ graffitied on it), a cash dispenser, empty industrial buildings. But there’s more. The presence of a thick green curtain and a folk image augment this fragmented collage to denote the ambiguity of a reconstructed interior and the crafted illusion of a stage.

We find more explicit references to performing arts and determined nods to the Beijing opera tradition in Behind the Scenes (2023), which integrates masks, face makeup, stage props and light fixtures. Here also, four female characters are placed in an eerie environment where paper lanterns coexist with owls and peach blossoms. A damaged wooden barge lies in the middle, where an attendant helps a seated woman holding a peacock with her elaborate headgear. The overall feeling is one of ceremonious care amid a chaotic backdrop. Another character faces the viewer, half of her face obscured by a mask. Who am I and who are you, she seems to whisper to us—a two-pronged question that echoes with Zhang’s own background.

“My past experience during the Cultural Revolution in China, a time of social unrest, widespread propaganda, violence and expected obedience to authority, has informed the underlying mood of my paintings,” Zhang said in the exhibition’s press release. His work is infused with two ambitions: to explore his own identity and to deconstruct his memories.

I had the chance to meet with Zhang, and we discussed his upbringing, with early memories of hardship marked by hunger, as well as the confusion and societal overhaul brought about by the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), a radical sociopolitical movement that sought to reeducate Chinese masses to the principles of its revolution with devastating human and socioeconomic consequences. Zhang learned about Chairman Mao’s passing on the radio after years of physically taxing manual labor assigned to him on a farm. Not long after this, he passed prestigious university entrance exams to study art, majoring in oil painting while retaining a keen and life-long interest in folk art.

Zhang recalled the spirit of the 1980s, a Golden Age of radical artistic experimentation, rethinking forms and subjects to break away from tradition and realism. 1985 was a year of ebullient change. With a group of other new-wave artists, he joined a seminal artistic retreat to discuss emerging contemporary Chinese art practices and participated in a landmark avant-garde show. He relocated to the United States as an accomplished and recognized artist in 1989—having had exhibits in the Beijing National Fine Art Museum and Shanghai’s Fine Art Museum—a fateful year for many of his generation. In the United States, he learned to survive, juggling odd jobs and sketching portraits in Central Park and Times Square, like one of his contemporaries, Ai Wei Wei. New immigrant life wasn’t easy, but Zhang persevered.

The title of the show remembers the ancestral Chinese tale of a fisherman who, seduced by the splendor of peach blossoms lining a stream, decides to explore more of it. In following the stream, he discovered a grotto that leads him to utopia, a community sheltered from political and social ills. But when he leaves and then tries to retrace his steps, he cannot find the place again. The tale engages with themes of idealism, nostalgia, corruption and truth, as well as the turns we take that lead to opportunities or missed chances. Emotions that immigrants intimately know.

Under this framing, Zhang’s paintings are an ode to dreaming, unleashing the power of uncanniness, and a remembrance of cultural upheavals. It’s not about chasing bygone days but rather, he proposes to examine the relationship between being and becoming as well as epistemic hierarchies. He plays with tropes and archetypes to engage with self-understanding.

“Land of the Peach Blossoms” is a narratively cohesive show in which the past and the future collide in frescoes of (im)possibility as the artist’s repertoire of operatic characters derides the cliches and prejudices that often assign migrants to fulfill external expectations. This is most evident in the way that Zhang chooses to paint empty, haggard eyes without pupils. In his experience, migrants are not seen as individuals but as a collective whole. They’re plural, as if their prior personality and lived past are erased upon beginning a new life elsewhere instead of new experiences being added to the soil of pre-existing personhood. The hollow eyes force us to confront that limiting, distant gaze in a role reversal.

Similarly, with the continued presence of masks and costumes, Zhang revives his love of the Beijing opera. He used to sneak backstage in Beijing and makes it a point to attend a performance every time he returns to China. Yet more than reacquainting himself with an infatuation, he uses operatic objects and codes to question the function of artifices and concealments for those who wear them and the audience.

“Immigrants have to play a role at first,” the artist tells Observer. But after a while, these layers peel, and they can be truer to themselves. “I do this work to send a message and to speak out, about race and about how I feel.”

“Land of the Peach Blossoms” is on show at Kravets Wehby Gallery through November 22.