“Isn’t one of your first questions, like: What the hell are you doing in Palm Beach?”

Here is Tom Ford, the King of Sex, looking still, at 62, very much like the King of Sex—if not terribly Palm Beachy. He’s wearing heavily distressed blue jeans and a blue denim shirt with few enough pearl buttons fastened to reveal an impressively muscular chest gilded in hair, plus black Chelsea boots and a Texas Timex—a gold Rolex Oyster Perpetual watch that he bought on Place Vendôme in Paris during his 10-year reign at Gucci.

Ford has agreed to an exit interview capping his historic three-decades-long fashion and beauty career, saying he is willing to discuss anything and everything under the condition that I come to Palm Beach, where he is currently living with his 11-year-old son, Jack. Since stepping away from fashion earlier this year, Ford has largely declined interviews—until this one. As we talk, I find myself thinking that part of the reason he acquiesced is simply because he’s lonely. “I’m not used to sitting around talking about myself anymore,” Ford says. “It feels very bizarre. I have no mate, no partner, no adult in my life. I talk about, you know, Minecraft, YouTube, Messi. So just having an adult conversation at all is a bizarre thing for me.”

In November 2022, Estée Lauder, Ford’s partner in his juggernaut fragrance and beauty business going back to its launch in 2005, announced that it had agreed to buy the entirety of his namesake label for a total of $2.8 billion. The deal made him, personally, a billionaire. It also signaled the end of Ford’s unprecedented run in the luxury business. Starting with his electric, star-making turn at a previously floundering Gucci, and continuing with the booming success under his own name, Ford’s persona and very visage transcended the insular world of fashion and became culturally synonymous with swagger, sex, and luxury itself.

When I ask Ford why he sold his company and, yes, what the hell is he doing in Palm Beach, the answer is the same: Richard’s death. Ford and fashion journalist Richard Buckley met in an elevator at a fashion show in 1986. It was love, Ford has said, by the time the elevator hit the ground floor. They were together for 35 years, and married for nine, until Buckley’s death in September 2021, after complications stemming from an earlier cancer treatment.

In the wake of that loss, Ford and Jack moved here full-time, into a 1920s mansion acquired in a house swap with a neighbor—a deal that reportedly carried a total value of well over $100 million. As we sit in the living room, Ford’s butler, Anthony, brings Ford a Diet Coke and me a glass of sparkling water. Outside, there is an occasional arrhythmic thud, which turns out to be Jack, who is running the length of the house pounding a soccer ball into a pair of nets.

This is an unusually quiet moment for Ford. We agree to call it the second intermission in his career—a break before the third act as a full-time filmmaker begins. Ford still delivers heroic doses of all his most recognizable personality traits: the impeccable old-world manners, the grandiloquent bombast, the devastating charm, and the outrageous provocations. But over the course of our time together, he also reveals a new sensitivity—and more than a little heartbreak. “Maybe a year ago,” Ford tells me, “I had to have knee surgery from tennis. So they had to put me under. When I went in, they said, ‘Who do we contact in case of emergency?’ And I literally had no one. So I put my PA.”

Our interviews begin with a three-hour session in Ford’s living room and continue over dinner in a corner booth at the nearby restaurant Le Bilboquet. (Ford picked me up from my hotel in his black Range Rover Autobiography, with Sirius XM’s Studio 54 channel playing.) They conclude several weeks later over Zoom.

It’s true. It’s a weird ghost town and even when it’s going, it’s a suburb of New York. That’s how I think of it. Two hours and 20 minutes. No jet lag. We’re going to London on Wednesday. Jack’s coming with me because, since Richard died, he’s terrified I’m gonna die.

Oh, yeah. I said, Look, I can fly. “But you could crash.” Yeah. I’m not gonna crash. “You don’t know that.” Okay. I don’t know that. So let’s say I go somewhere and a plane crashes, you’re still alive. If you’re with me, you’re dead. Which would you rather be? And he said, “I’d rather be with you.”

Richard and I lived in London for 22 years. Paris for 10, Milan for four. But this time, we moved back to LA from London because he was sick. [The house in LA] was basically Cedars-Sinai. And every contemporary memory I have of it is not good. It was a sad house. After Richard died, I was driving back from a screening at CAA that Madonna was having for, like, four people. The streets were deserted everywhere. I was so used to Richard being in the seat next to me. And I felt so lonely. I just thought, This is the loneliest place. I have to get out of here. I thought, Where can I give Jack the life he’s used to? Which is tennis every day. Soccer every day. Warm weather, swimming pools. A liberal grade school. I have a history with Palm Beach going back to when I was at Gucci. After shows, I would rent a little place here, just come and do nothing. Lie by the pool. You know, Anne Rice, in one of her vampire books, wrote that every 150 years, vampires had to dig themselves down into the ground in order to come back up eventually and appreciate life again. That it was all just too much. And that’s what I feel this is—this is like a reset. I needed that to figure out act three.

There are several reasons I sold my company. I felt, after 35 years, I had said everything I could say with fashion. It’s important to know when to get off the stage. I loved making the two films that I made. That was the most fun I’ve ever had in my entire life. I’m 62. Hopefully, I’ll remain somewhat together until 82. So I wanna spend the next 20 years of my life making films. And the clock is ticking. And so it was time to say goodbye to fashion. Fashion is a younger man’s game. It is the world of people from 30 to maybe 50. I’m 62. I’m living in your world. It doesn’t mean that I don’t have something to contribute. I do think certain professions get better as they get older. I think writers sometimes have a perspective that comes with age. Architects, for some reason, really get good the older they become. Designers rarely change the world of fashion at 62. I did it at 35, maybe until 45. Then I shifted into the moment when you become a household name and you make a lot of money.

Richard’s death. Boy, talk about mortality. When someone dies, their eyes are open. You can’t close them. It’s not like in the movies where they do this [Ford passes his hand over his eyes] and they stay closed. They pop open. Wow. I spent two hours with him, talking to him because I wasn’t expecting him to die that particular day. You know, slipping his wedding rings off. Taking off his watch. Flipping his body over to take his wallet out before they took him away. I felt like I was robbing him. Talk about driving home the idea of a limited time on the planet. It was like, I really want to make movies. Clock’s ticking.

I was.

Yeah.

I rearranged the furniture. I literally always did.

I went to a little high school in New Mexico. Santa Fe Prep. I was very shy. I was a very good student. And, um, this will sound egotistical.

I had no idea that I was attractive as a kid. Nobody told me that. In high school, when I hit puberty, all of a sudden every girl fancied me. I was on the ski team. I had girlfriends. I had sex at a pretty early age. I drank a lot. I got high a lot.

Well, pot was the norm, but the kids at the school had enough money that cocaine was readily available. On the weekends we would all go up to the spot called The Hill and open the car doors, turn on the stereos, get really drunk, get high. And then we’d have a party at someone’s house where everyone would get naked and get in a hot tub. It wasn’t quite Euphoria, but it was maybe more advanced than kids today. I don’t know.

I wore what we called in New Mexico “Vasquez” hiking boots—I think they’re really called Vasque. Levi’s 501s, a Brooks Brothers button-down shirt. A tweed jacket or a down ski jacket. It was a prep school. So it fancied itself an East Coast school. If you were lucky you got into Princeton. I got early rejection to Princeton, and I ended up going to NYU.

How I got to Studio 54—and with Andy Warhol, the very first time—is like something out of a movie. I was living in Weinstein dormitory at NYU. Which is made of cinder block. I had two roommates that drove me insane. I guess I was a little spoiled. So I literally was sitting in my room and I said, Please God, let something happen to me.

And a young man called Ian Falconer would come up to me every day in art history wearing a little Fair Isle sweater with blond hair. And I just thought, poor thing. He has no friends. He’s glomming on to me. I had no idea he was gay. I had no idea he was trying to pick me up. So he was at the door to my dorm room and he said, “Do you want to go to Studio?” So I put on my blue blazer. He said, we’ve gotta go by a friend’s house. So we go and the two of them kissed on the mouth as they greeted. It was all guys and they all seemed to have Lacoste shirts [with the collars] turned up. So I thought, Okay, these guys are gay. Well, I’ve always kind of been curious about this. And I just belted back the vodkas. Then Andy came by. We got in a couple of those great Cadillac limousines and went to Studio. When you passed through those doors, you couldn’t even believe it. There was a long hallway and it was mirrored and painted gold. It smelled like coke. Everyone was doing drugs completely openly. By the end of the night, I was giving Ian Falconer a blowjob in the cab on the way back to his house on Eighth Street and Fifth Avenue, which he shared with Patrick McMullan. I remember waking up the next morning in Ian’s loft bed. Thinking, What the fuck did I do? And I remember saying to him—you’ve seen it in movies—“This was great, but, you know, I’m not gay.”

No. A couple weeks later, we were going out and I was cool with that.

I realized that architecture was way too serious for me. We had a trip to Moscow and I’d gotten sick and I stayed in my hotel room, and something had been bothering me. And in the middle of the night I realized I love fashion. I should be a fashion designer. So [after graduation] I drew up a portfolio. I could sketch pretty well. And I went around Seventh Avenue and I got a job.

Marc [Jacobs] hired me. At that time, he was creative director of all Perry Ellis. And I remember being very jealous that he was younger than I was, but somehow he was more successful.

I was pragmatic enough to know, even at that time, that if you become famous as a European designer, you are global. If you become famous as an American designer, you are American. You know, Calvin Klein in Europe meant nothing. Marc became a global brand because he went to Vuitton. Had he not gone to Vuitton, the rest of the world wouldn’t know who Marc Jacobs was. So I knew that, and I thought, If I’m gonna work hard and be a success as a fashion designer, I need to go to Europe.

It was a stepping stone. Maurizio [Gucci’s] dream was to make it an Italian Hermès. Which it had been in his childhood. It was a good dream and a good idea, but it wasn’t fashion. They didn’t really make clothes like people think, and they didn’t really have big runway shows. So I thought, Well, if I learn all of the manufacturers, and how everything works in Europe, I’ll start my own brand. And then I didn’t need to, because once I became creative director, it felt like my own brand. I grafted my personality onto the Gucci brand.

I would give the models a talk right before the show, and I would say with my microphone—after I’d already had the drinks—“When you walk down this runway, everyone in this room should want to fuck you. Everyone.” Now I didn’t do that same speech for the last five years. I can’t say that to models anymore, “Everyone should want to fuck you,” but I used to always say that. And it was important even in the way they looked. In the way they walked.

Yes, absolutely. I was in Florence at our factory. It was early in the morning, 8:30 a.m. Maurizio had an office across the street from my office, and from my window I could see the steps where he was shot, but I wasn’t there. I think everyone’s first thought was that it was a Mafia hit. Ridley [Scott] didn’t put this in the movie [House of Gucci]: At one point Maurizio had to cough up 40 million bucks to Investcorp. He didn’t have the money. No bank was going to loan it to him. And he magically came up with it. You assumed, well, the Mafia gave him the money. You’re in Italy. Also, those scenes in the Ridley Scott movie where I come in and meet with Maurizio and say, “I see men in thongs,” none of that ever happened. I didn’t see men in thongs at first. That came later [laughs].

It was terrible. After that show, Richard said, “You’ve gotta find a way to make it sexy. The girls have to want to wear the clothes. The girls don’t want to wear those clothes.” That was all he had to say. And it was like, Yes!

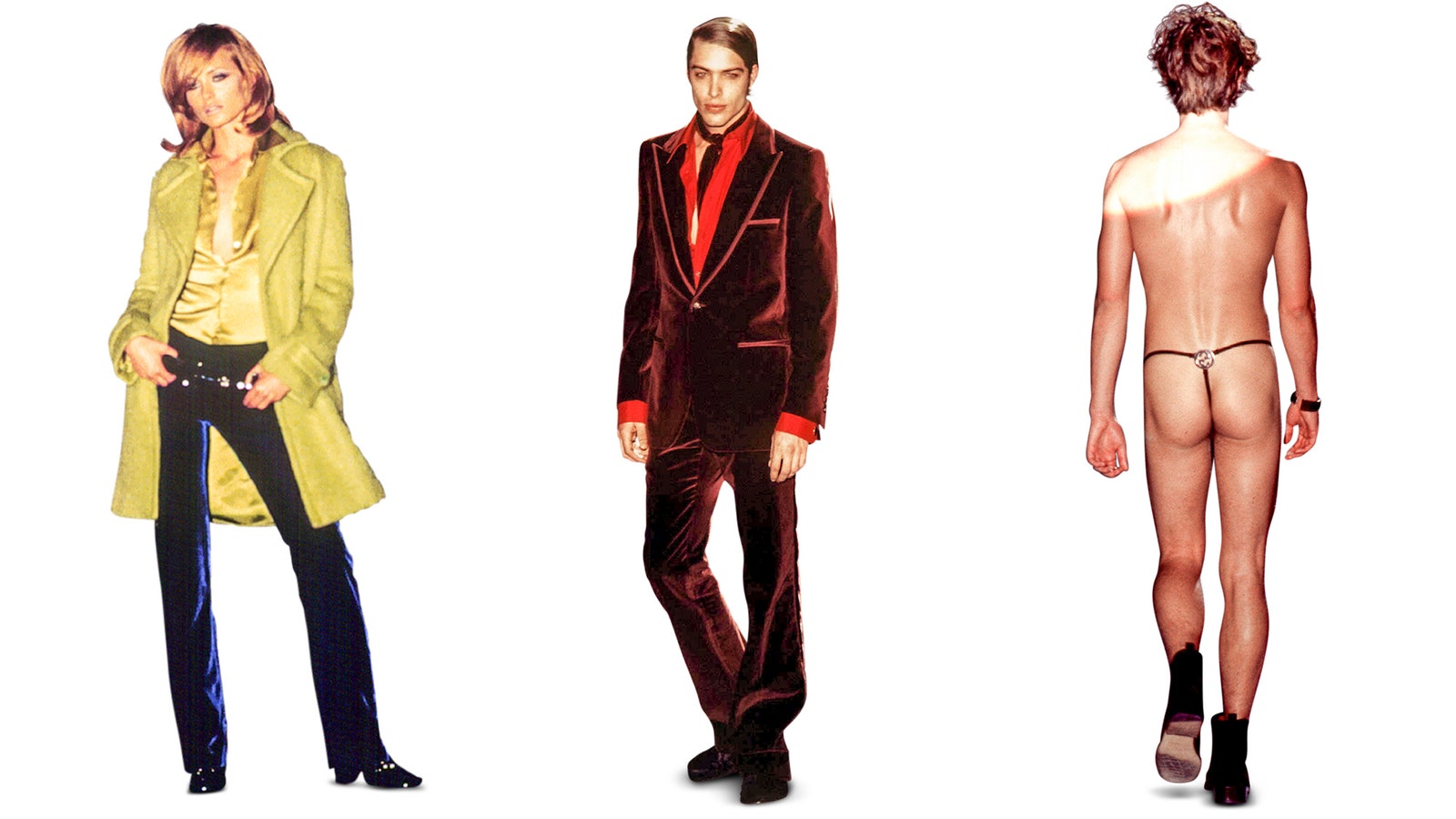

It was with men’s. There was a men’s show in Florence. At that time I was young enough to still actually go out to clubs. And you could feel this ’70s revival starting up, so I went deep into that. I took the Gucci loafer for men, and I made it in patent leather car finish. And I used tons of velvet and color, and silk shirts open to here. And it worked. And so I thought, Okay, well I’m just going to carry this through for women. And I did. Although it was the next show [fall 1996] for Gucci that was the closest one to what is still my own permanent taste—the show with the white dresses with the cutouts, and the women in the tuxedos. It was more understated in a way, but it hit a chord in the room. I could feel it. Back then people didn’t have phones. You had 13 minutes to introduce something that should jar them. And then convince them of it, and then make it so beautiful that they would cry.

Oh, I was so into it. Feeding off of it. To really be successful at women’s fashion, you have to live and breathe nothing else. Twenty-four hours a day. There can be nothing else in your life.

It’s easy. You have to keep a thread of yourself in it. People used to say, “How do you make everything so sexy? And why do you make everything so sexy?” I don’t start out saying we need to make a sexy dress. I look at a dress and I say, “I can’t see her waist. I want to see that. I can’t see her ass. I want to see—where are her tits?” When I was cutting the underwear for Tom Ford men’s, I put every pair on. And if you cut the thighs tight, but you leave a little extra fabric in the middle, you have a bigger dick. And, I’m sorry, when you’re walking around in your underwear, you want to look like you’re well-endowed, even if you’re not. I mean, no matter who you are, you want a bigger dick. Probably people with dicks like this [holds hands about a foot apart], want a bigger dick. The point is, there’s a through line through everything I do. If I’m cutting a men’s pair of pants, their ass has to look good. And you have to look taller, in better shape, your waist has to look good.

It’s true.

That was it. I kept finessing that for the rest of my career. I had a 10-year run. And I think that’s all you get. A PR person would tell me not to say that. But that was where I moved the needle culturally. I was in my 30s and early 40s. How many years will Taylor have it? I mean, the Beatles. When you actually go back and look at how long they existed, it was like seven years, eight years. Nothing.

I mean, if you get that much time—that’s amazing.

Well, what’s the statute of limitations? That’s a hard one. When I wanted to show those G-strings, it was hard to get a really good male model. Finally, one of them was like, “Yes, I’ll wear the thong.” Thank God. At the show, he was about to go down the runway and I would check everyone, right? I looked down and it was like Peter Cottontail. So much hair sticking out of his ass crack. I said, “Give me the trimmers.” I bent him over and I literally just went zip! And then I said, “Okay, you can go out.” And out he went.

It played out in the papers every fucking day back when it was happening. It was in the Financial Times, in the Wall Street Journal. It was everywhere.

We created Kering. There was a name change, but we created Kering.

We had $3 billion to invest, courtesy of our deal with François, and we needed to grow. So the first acquisition was Saint Laurent, and it was a billion dollars. And it was done only if I would design it. Because at that time, everything I touched, worked. Not always the case, but it was definitely the case then. We had to deploy this cash, but my criteria in figuring out who to invest in was: I’m the only creative person here. In case something happens, you can’t have a company that big with one creative. Who do I admire? Whoever those people are that I admire and I’m jealous of, we need to get. And so I went after Lee McQueen.

I was a commercial fashion designer. That doesn’t mean there wasn’t an artistic element to what I did. But I was a commercial fashion designer. Lee was an artist who happened to use the medium of clothing and fashion shows to express himself. At that moment in time, [current Louis Vuitton artistic director of womenswear] Nicolas Ghesquière was hot. Absolutely hot. And he did something totally different than what I did. I wanted him to start his own collection. He didn’t want to do that. So we bought Balenciaga and he was at Balenciaga. Stella [McCartney] addressed a totally different customer that we did not have. She was onto all of this environmental stuff, way ahead of everybody else. And so that made sense. With Bottega [Veneta], I went after Tomas Maier. He and Richard were best friends back in the 80s, and he had the best taste. In assembling it, you needed brands that didn’t compete so that you could have a very well-rounded portfolio. And people that I admired. So that’s what we did.

I mean, why not? It’s business. I have tremendous respect for Bernard Arnault. I mean, my God, how do you build what he has built? And his kids, they work, so that has to come from the parents. And the same with François Pinault and François-Henri Pinault. François-Henri and Salma [Hayek] and I are very friendly when we see each other. You know, I like him.

Business. It’s business.

Oh, I am half businessman. Half designer. I always was. I have a gift. My greatest gift is, you can lay five pairs of shoes down in front of me, and the one that I pick will be the commercial one. I have commercial taste. Maybe, hopefully, at a high level. But if you’re not making money, you can’t do what you want. There’s an intuition that comes with the kind of business brain I have. I have a certain feeling about it, and I know that it’s the right business decision, even though it makes no sense to someone who’s just looking at the spreadsheets. You know what’s coming next. You feel it.

I have no idea. And that’s one reason I’m stepping away.

It’s gotten so far away from why I got into the business, which was to make a beautiful garment that made a person stunning and incredible-looking when they walked into a room. That was why I became a fashion designer. So this new—what it has become is something that maybe I understand, but I don’t necessarily like.

I have, since, calmed down a little bit. But I read in a GQ blog or something where Peter said he was given a blank page to start Tom Ford menswear.

It really upset me because starting Tom Ford menswear [in 2007] was one of the things I’m probably the most proud of in my entire career. I was used to being at Gucci and when I wanted something, I just had it made. And all of a sudden I couldn’t—I didn’t have any clothes. So I brought in all the clothes from my wardrobe. I had everything made in my size. Luckily, I’m a 48 regular, which is the fitting size. So I fit all the suits on myself. Peter wasn’t able to start for a while. He was still John Ray’s assistant at Gucci. So those first few years, that collection was built on me. It was enormously personal. I literally sent my sofas out to be copied for the stores. I loaned art from my house to the stores. It was one of the things I’m the most proud about because it was the foundation of the company. So I got in touch with him [recently]. I said, Pete, I don’t want to say these things publicly and contradict you, but it wasn’t exactly a blank page. I was very worked up about it. I’m a lot less worked up about it now. You know, when you sell your company you’re prepared for anything. And I really am prepared for anything. Whatever direction they go, Peter’s blank page starts now. But, you know, that’s my fashion legacy. The Tom Ford company, the Tom at Gucci, the Tom at Saint Laurent—that’s mine. It’s tied up in two neat volumes with a bow.

We didn’t talk. We exchanged emails because what I had to say, I wanted to say carefully, and I wanted to take away the emotion. And then I sat on the email for a day, which I think is always the best. I wasn’t upset about anything he sent down the runway. I thought it was beautiful. I thought it was very well-made. He was certainly in the spirit of the brand. I think women’s fashion is very hard. I think now he’s going to need to do something somewhat revolutionary in the way that Alessandro Michele did with Gucci. Anyway, it’s easy to sound petty—I’m self-conscious in a way even admitting that I feel this way. Because I’ve been very lucky. I’ve had a great career.

Well, it’s very nice, but I didn’t give it a lot of thought. Fashion is cyclical. That was, God, 20 years ago. I’m glad that what I did has come back again.

Oh, God. Who embodied the Tom Ford man? I mean, me. I built it for myself. Brad [Pitt] was the very first one [to wear the brand]. And at the beginning I had an exclusive thing with Brad. I would only dress Brad. Brad only wore me, or he wore me to his big events. At Gucci we were sending clothes to everybody, and it lost its cachet. So when I launched Tom Ford, I went to Brad and that was who I dressed.

No. I’ve never paid a single celebrity to wear my clothes or come to a show, ever. Ever, ever, ever. And now everyone does.

The alcohol was a gateway to the drugs. And, you know, my son hasn’t read any of this stuff yet. He will. And I’ll need to talk to him because he shares the same genetic background that I do, which is English-Irish. I think we’re predisposed. My father was a heavy drinker. But the alcohol, you know, was a gateway. [Cocaine] is very popular in the fashion world. I realized it was a problem when I started doing it in the mornings.

Well—

Yeah. I’d light a cigarette and, yeah. It was a problem. But I stopped, because I would be dead. I had a therapist who helped me. It took about a year of stopping to really stop. Then I got a stack of books on alcoholism and started reading about ethanol and what a poison it is for your body. I realized that I was in a phase of proper alcoholism. I would hallucinate in the morning. I would think I was killing ants and [smacks arm of chair like there’s a bug on it]. I would black out.

I realized one day that I was gonna die. And that I created something that will live on past me, because there is too much money involved. So whether it’s 50 years from now or five years from now, a lot of stuff that I hate will be generated. People are gonna do a lot of shit with it that would make you turn over in your grave. Why not let ’em do it now? Just do it while you’re alive. I mean, do you think Balenciaga or Givenchy—I mean, Hubert de Givenchy would die if he saw, and so would Cristóbal Balenciaga. So why not have fun for the rest of my life and do something I find really creatively exciting?

Well, when we were gonna sell the company, we went to Goldman Sachs, and at the beginning they put together a presentation, as you do when you’re selling a company and going out to multiple bidders. But they put together a presentation that was very me-heavy. I was like, Why would anyone buy this if the business is so dependent on me? I said: Put the presentation together as though I’m dead. It still has my name on it [Ford reaches inside the waist of his jeans and pulls out his underwear to show the Tom Ford waistband] but—

Yeah.

Well, especially with jeans, because these have rips. And any minute another rip is gonna happen. Probably 10 years ago—this is true—before I was wearing underwear, I looked down and an actual testicle was completely out.

As a director, it takes three years to make a movie. I have maybe time for five more movies in my life. So they have to be meaningful.

One is an original. An extremely personal thing.

Completely from scratch. Then another is a book from Anne Rice. We started the process in 2004, while she was alive, obviously.

It’s absolutely expository. I start every morning at nine o’clock. I sit down and I work from nine until one. Even if I don’t think I have anything to say, I type. The beauty really for me of filmmaking is the writing. Because when you’re writing it, it’s perfect. Nobody fucks up. The clothes are perfect. Everyone’s saying it exactly the way you want. It’s absolutely clear. The hard part for me is shooting—because this didn’t work, that didn’t work. You’ve got to keep moving. You’ve got a schedule.

I had it for a little while, maybe about the same time I stopped drinking. It was one thing that compelled me to write A Single Man, because Christopher Isherwood was very spiritual, in an Eastern way. I was reading the Tao Te Ching every night before I’d go to bed. I’d read one of those very potent sentences, and I was able to have it.

I need to try again. I’m very pragmatic. I can’t actually comprehend the science, but the universe is so vast—our planet is so insignificant. There was a film in the 1950s with Anne Francis that was so ahead of its time. The idea is, maybe our purpose in evolution was to create an AI being that becomes a consciousness. It will be like God, where we have created it in our image and it will hold every bit of all of us. Ultimately, we will be unnecessary. Maybe our purpose in evolution is to end biological life, and to figure out how to create the next level of being—an electronic consciousness. What was the movie called—Forbidden Planet? Or Lost Planet? I don’t know. Anyway, whatever. It’s not that interesting. Turn that recorder off, let’s have dinner.

Will Welch is GQ’s global editorial director.

A version of this story originally appeared in the 2023 Men Of The Year issue of GQ with the title “Death, Sex and Money: The Tom Ford Exit Interview:

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.