Ah, the 90s: the era of slap bracelets, Tamagotchi, and hypercolour t-shirts. And of course many spectacularly large and very expensive movies, spanning extraterrestrials, on-the-run fugitives, masked orgies, and everything in between.

This list focuses on Hollywood-produced 90s blockbusters that cost a pretty penny: somewhere around $50 million at least. Here are the best, picked by Luke Buckmaster.

See also

* The 50 best blockbusters movies of the century so far

* All new streaming movies & series

A tale as old as time and a song as old as rhyme, according to the ancient wisdom of a singing teapot. My pick of Disney’s animated movies from the 90s (I’m also very fond of Aladdin) is sheer elegance, reinvigorating an old fairytale and homing in on its humane messages.

A super buff Nicolas Cage, rocking a hillbilly mullet, is in fine form as an army veteran whose mission to “save the fuckin’ day” involves thwarting the plans of a dangerous gang who’ve hijacked the prison plane he’s on. Here the Bruckheimer machine is particularly well oiled—with big juicy set pieces, snappy writing, a great pace, and moments that would become legendary—including Cage’s demand to “put the bunny back in the box.”

Robert Zemeckis looks up into the cosmos, asks “is anyone out there,” and gets a cold-hard answer: of course there bloody well is. Jodie Foster’s stargazing scientist uncovers a message from aliens, in an audacious if a little twee sci-fi that discusses the relationship between science and imagination. Plus the tension between progress and the usual political and religious forces attempting to suppress it.

This near-single setting thriller is sensational, albeit a tad restrained by Tony Scott’s frenetic standards. Onboard a missile submarine capable of instigating WWIII, Gene Hackman’s cigar-chomping captain says fire away, while Denzel Washington’s Lieutenant Commander urges resistance. Like a filmed play, which is unusual for a blockbuster, Scott uses the sub as a political melting point representing clashing philosophical perspectives.

One year before The Matrix, Alex Proyas’ gorgeously noirish head trip also presented a world where a reality-bending hero (Rufus Sewell) punctures through an alien simulation. A wet, surreal look is conjured from start to finish, this universe positioned somewhere betweeen wakefulness and sleep, reverberating like a familiar nightmare. The final showdown between hero and villain is terribly hackneyed, but everything else is great.

The good: the world gets Morgan Freeman as the US President. The bad: it also gets a whopping big comet heading straight for it. A rare example of a blockbuster that’s well respected by scientists, Mimi Leder’s disaster movie has no chest-beating, no gung-ho beefcakes saving the day. In fact, no saving the day full stop: astronauts are sent to destroy the comet but some obstacles can’t be avoided, some wars can’t be won. This is a film about intelligently responding to crisis.

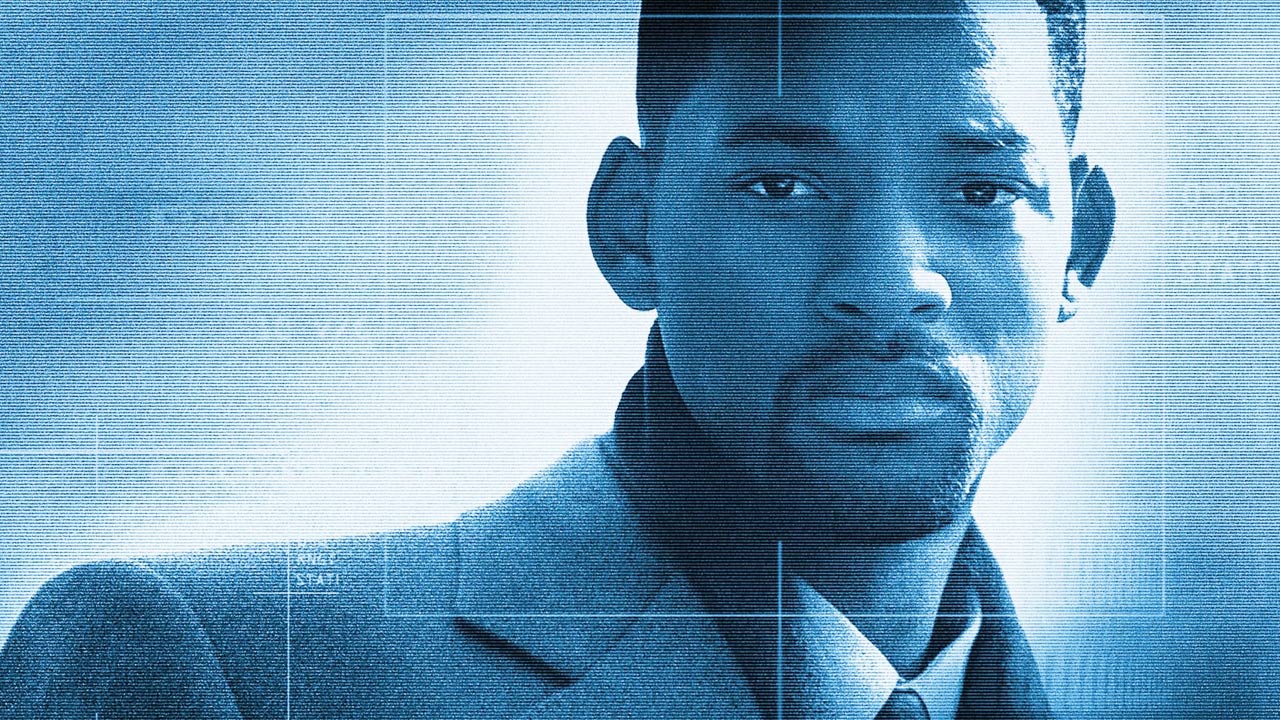

Like Will Smith’s distraught lawyer, who unwittingly becomes an enemy of the state, this on-the-run classic is in a hell of a rush. Tony Scott brings a jittery, volatile energy, as if the screen itself could crackle or combust. The surveillance technology used to follow Smith’s protagonist of course has dated, but that just makes this film more interesting—as a kind of tech-paranoid alternate world time capsule.

Stanley Kubrick’s intensely moody drama is fascinatingly odd and grand, the tone Edgar Allan Poe with a dash of soft porn. Tom Cruise’s New York doctor, married to Nicole Kidman’s former art gallery director, goes on the hunt for extramarital thrills and naturally ends up at a masked orgy. When I first saw the film in 1997, the responses of myself and my companions perfectly reflected the film’s divisiveness: I loved it; one of my friends hated it; the other fell asleep.

The premise of John Woo’s irresistibly operatic action movie, caked with carnage both cartoonish and poetic, involves a cop going so deep undercover he has surgery to wear the villain’s face. This enables Nic Cage and John Travolta to play both the good guy and the bad guy, a task they take to with deliciously over-the-top aplomb.

The first rule of Fight Club is you don’t talk about Fight Club. But here we are, slack-jawed all these years later, still gassing about David Fincher’s brilliantly incendiary thriller. Longing for purpose, feeling, anything, Edward Norton’s unnamed narrator goes looking for trouble and finds Brad Pitt’s Tyler Durden jabbing at his psyche. This twisted vision of toxic masculinity captures the malaise of the 1990s, and remains shockingly awesome.

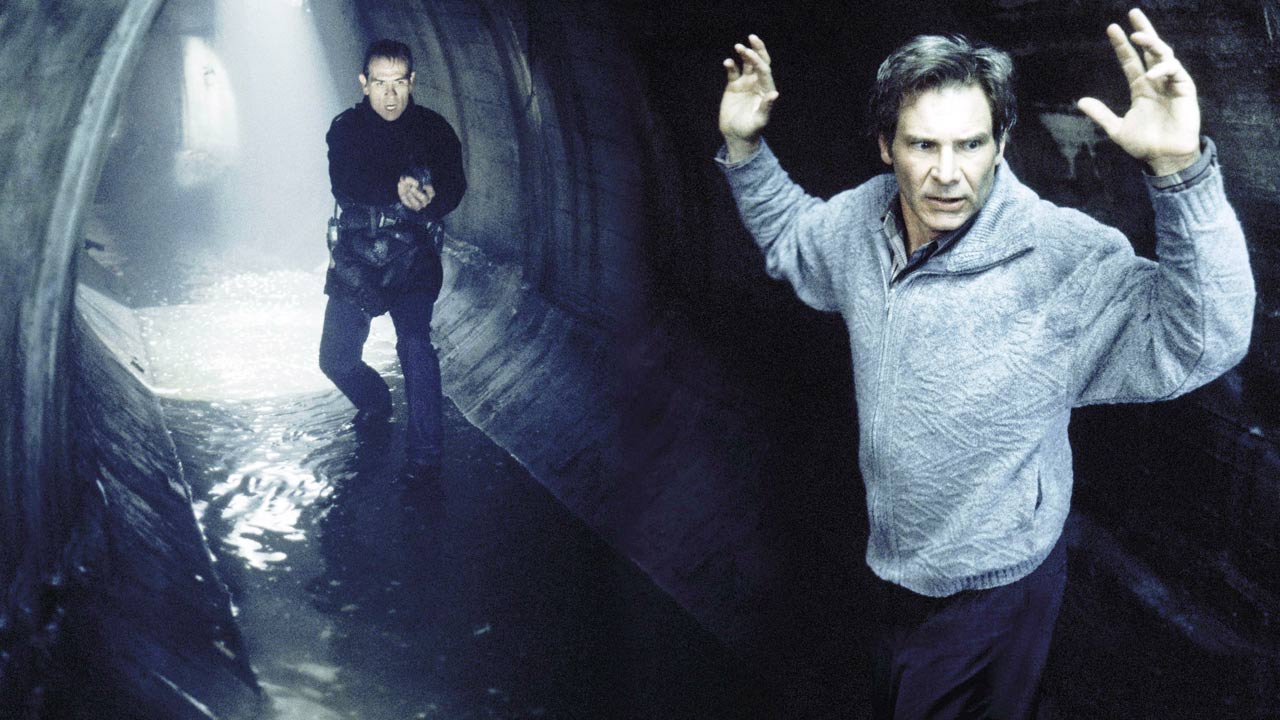

Andrew Davis’ 1993 classic—starring Harrison Ford in one of his best performances—is a muscular, pulse-pounding flick, with a tight sense of narrative economy. Within the first 15 minutes the wife of Ford’s protagonist, Dr. Richard Kimble, has been killed; he’s been falsely convicted of the murder; and he’s escaped from custody and is on the run, desperate to prove his innocence. Tommy Lee Jones (also bringing his A-game) is the gruff U.S. Marshal tasked with bringing Kimble in.

What do you get for the man who has everything? David Fincher’s terrific thriller could be interpreted as a commentary on the experience economy, or a critique of the bored middle and upper classes. Michael Douglas’ snooty investment banker signs up for a mysterious “game” which is possibly pure entertainment, and possibly pure extortion. The “real or not” question is beautifully teased as the set pieces scale up.

Costing around $36 million (not much for a blockbuster) and under-performing at the box office, Gattaca arguably doesn’t belong on a list full of big and brassy money-earners. But have a heart, because this film certainly does: it’s a wonderfully inspirational underdog-triumphs narrative starring Ethan Hawke as an aspiring astronaut, who, in a not-too-distant future, defies new forms of genetics-based prejudice. The “I never saved anything for the swim back” scene gets me every time.

Heat

Streaming Now

Al Pacino and Robert DeNiro face off as an obsessed cop and a big-time thief in Michael Mann’s exalted crime drama, set in the concrete jungle of Los Angeles. The director’s stop-start momentum switches between bursts of action and simple dialogue exchanges, the most famous and memorable transpiring between the two lead actors in a diner, over a cup of coffee.

Sheer, stupid, irresistible popcorn spectacle, cooked up for the bleachers seats but also very well crafted. When aliens land on earth and zap the White House to smithereens, Will Smith declares he’ll “whoop ET’s arse.” Disaster maestro Roland Emmerich runs with the madness full tilt boogie, summoning Randy Quaid’s drunk pilot to save the day. This movie makes you want to stand up and cheer.

Robin Williams plays a character who got lost in an alternate universe as a child, and is returned to reality when new players (Kirsten Dunst and Bradley Pierce) of the titular board game roll the dice. Joe Johnston’s 1995 hit is to some extent a coathanger for special effects—but it’s unusual to see a family film so alive with paranoia, so dripping with dread. Jumanji was under-appreciated back in the day but time has been kind to it; even the special effects still look pretty good.

Steven Spielberg’s dinosaur theme park is so vividly rendered it feels like we’ve been there for ourselves. Not that we’d want to, given how things turned out. Widely considered a turning point for computer-generated effects, Spielberg elegantly mixes real and virtual elements and suspensefully draws out his set pieces.

The Wachowski sisters’ mega blockbuster needs no introduction; labels like “classic” don’t come close to doing it justice. Keanu Reeves snapped out of ordinary life to fulfil a Christ-like call to arms, taking on the gods of the computer program dictating our lives. The “bullet time” sequences inspired countless copies, although attempting to trace the impact of The Matrix is folly. This movie is a genuine phenomenon.

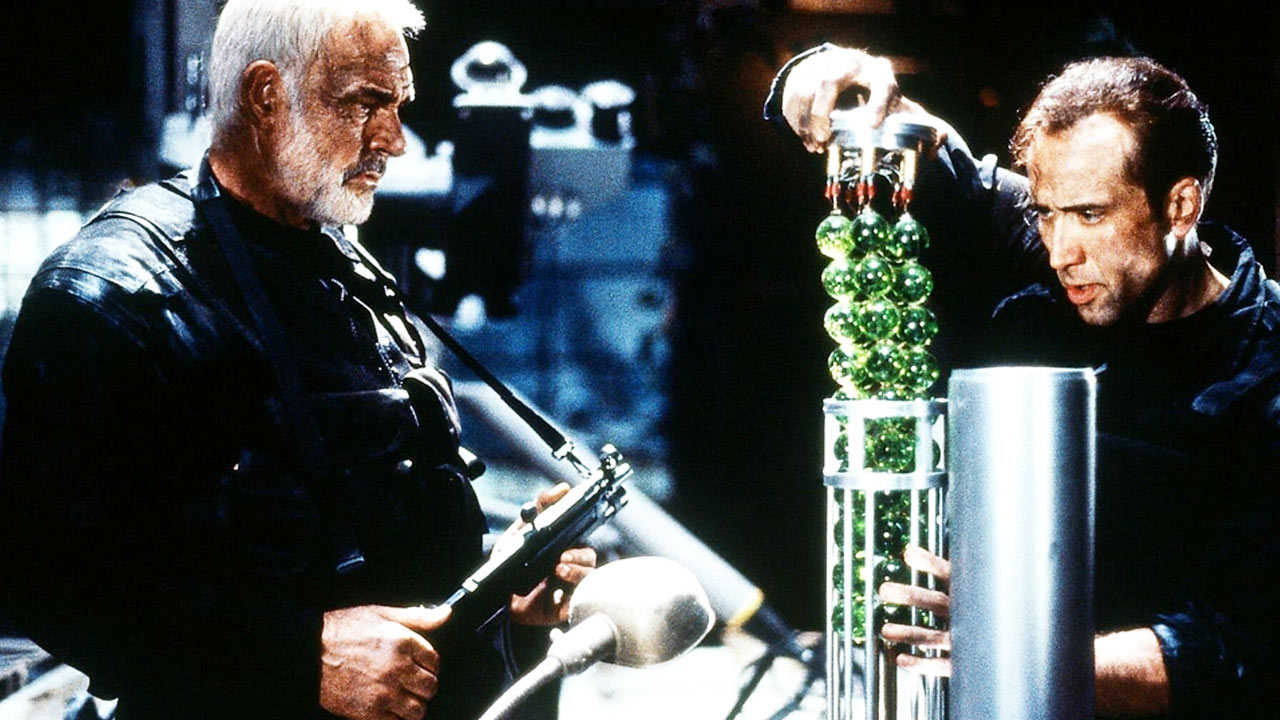

When Nic Cage’s FBI agent Stanley Goodspeed and Sean Connery’s crotchety ex-con arrive at the titular former prison on Alcatraz Island, this perennially rewatchable production—a stand-out of 90s action cinema—follows a video game format. They find missiles, defuse them, take down baddies, repeat the cycle. Everything in this film works, from Cage and Connery’s testy chemistry to Michael Bay’s sizzling direction.

Speed

Streaming Now

Baked into the premise of this terrific action fest, starring Keanu Reeves as a SWAT officer who boards a bomb-rigged bus that’ll explode if it slows down, is a narrative justification to keep moving. Yet director Jan de Bont doesn’t rush his key scenes, extending them methodically and letting moments breathe before taking the air away. Reeves and love interest Sandra Bullock are pleasant but flat; Dennis Hopper makes up for it as a gloriously shit-eating baddie.

Paul Verhoeven’s wily critique of right-wing war mongering was sorely under-appreciated at the time of its release, but clawed back its reputation and is now deservedly regarded as a big-thinking cult classic. How did critics get it so wrong? Set in the distant future, humans go to war against a new set of alien enemies, pushed along by the same old elements: propaganda, jingoism, ignorance, xenophobia, and the evils of the military-industrial complex.

Fear of a robotic uprising has long stimulated the public imagination—rarely as memorably as in James Cameron’s 1992 masterpiece. Larded with gripping chase scenes, which have aged not one iota, the villain from its predecessor—a cyborg played by Arnold Schwarzenegger—returns as a reprogrammed good guy, initially butt naked but soon to kick ass in an iconic leather jacket and black sunnies.

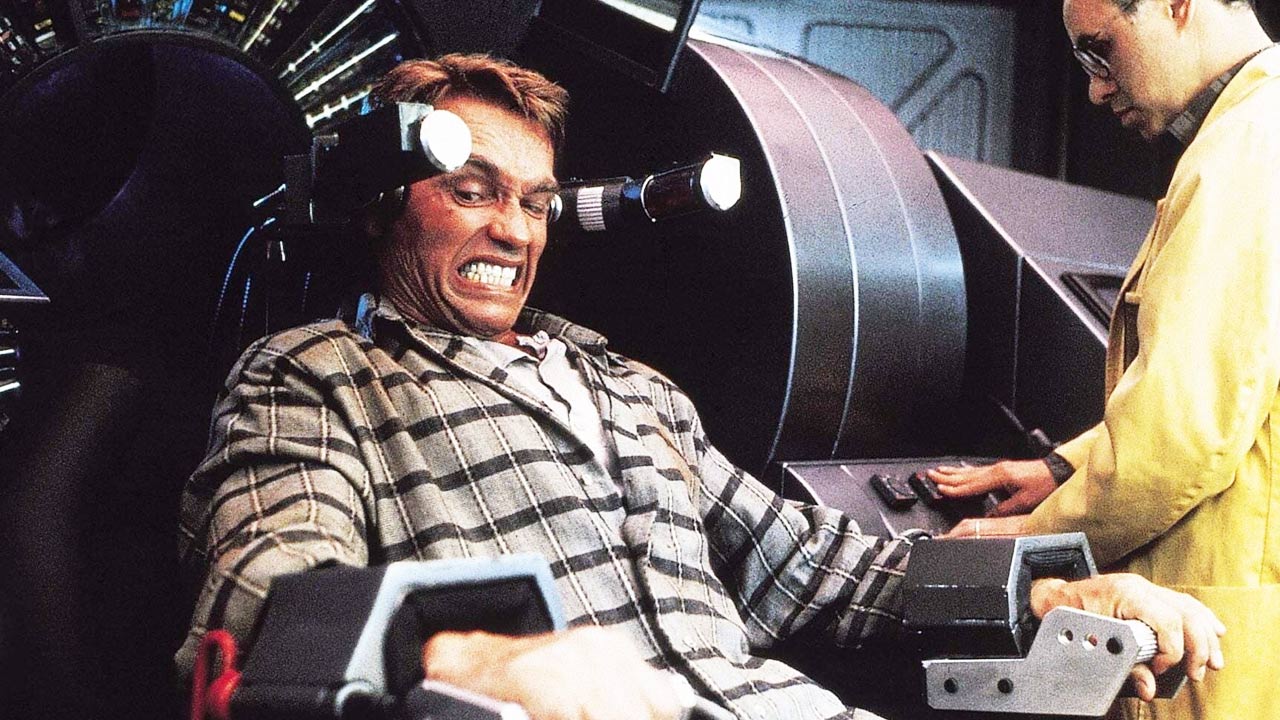

Is it real, or a simulation? That question has rarely been more enjoyably teased than in Paul Verhoeven’s rip-snorting Phillip K Dick adaptation, which follows a construction worker (Arnold Schwarzenegger) who partakes in a hallucinatory new recreation then can’t sort out whether it’s working. The sets contains lots of zany flourishes, from robot cabbies to that legendary three-breasted woman.

Pixar’s most famous franchise expresses the divine imaginative potential of commodified playthings, and acknowledges their roots in mass consumption. The first Toy Story heralded the arrival of Pixar, and of Buzz Lightyear and Woody—the latter confronted with the terrible possibility that his time in the spotlight might be up. It’s smart, joyful entertainment, told with light and shade.

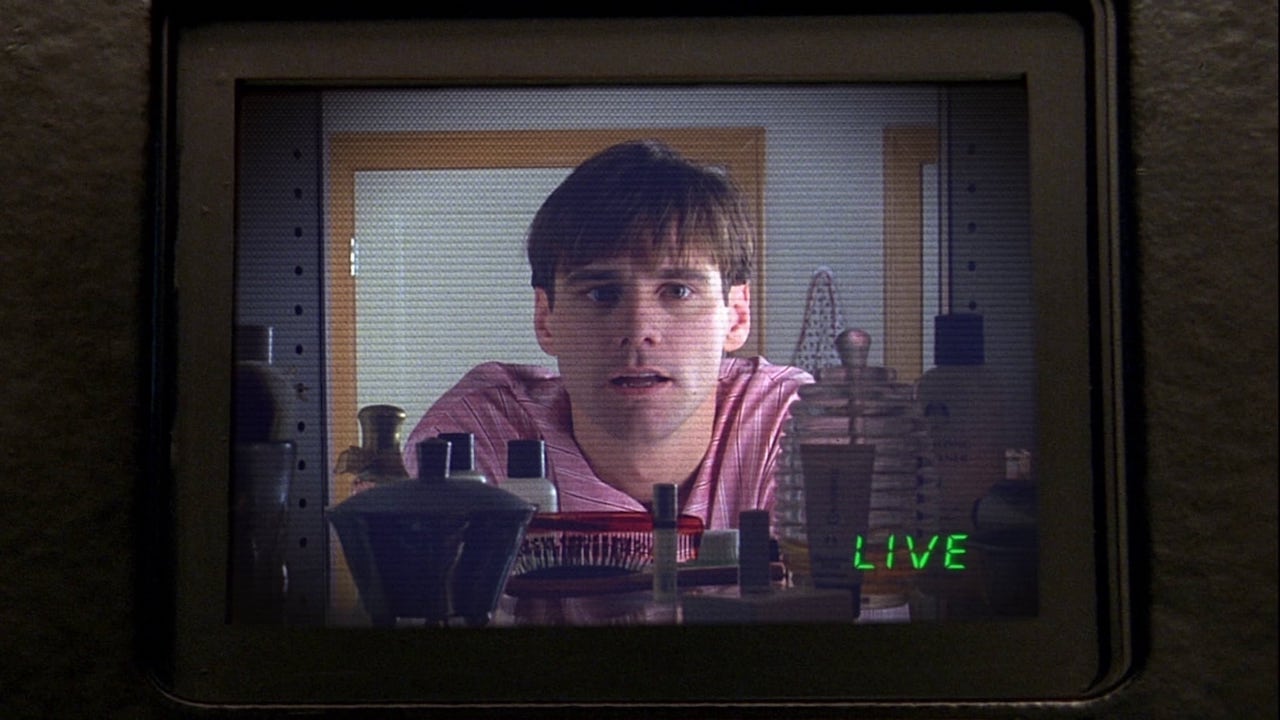

Peter Weir brilliantly fleshes out a simple premise: what if somebody was the star of their own reality TV show, and didn’t know it? The story of goofy insurance salesman Truman Burbank (Jim Carrey), whose voyage of personal discovery reveals the fraudulent nature of his reality, springboards several interesting discussions—including exploitative voyeurism and the end of privacy.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.