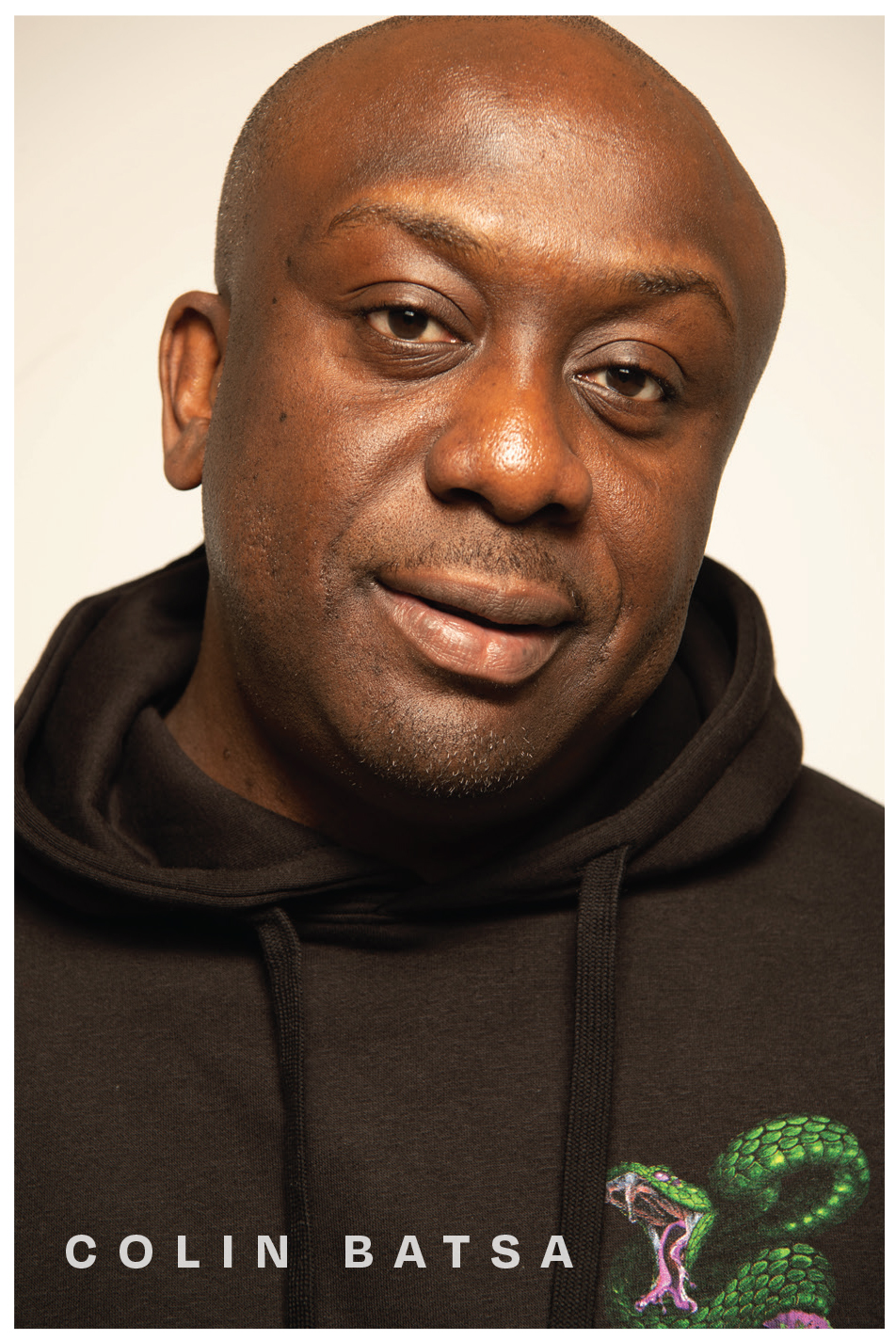

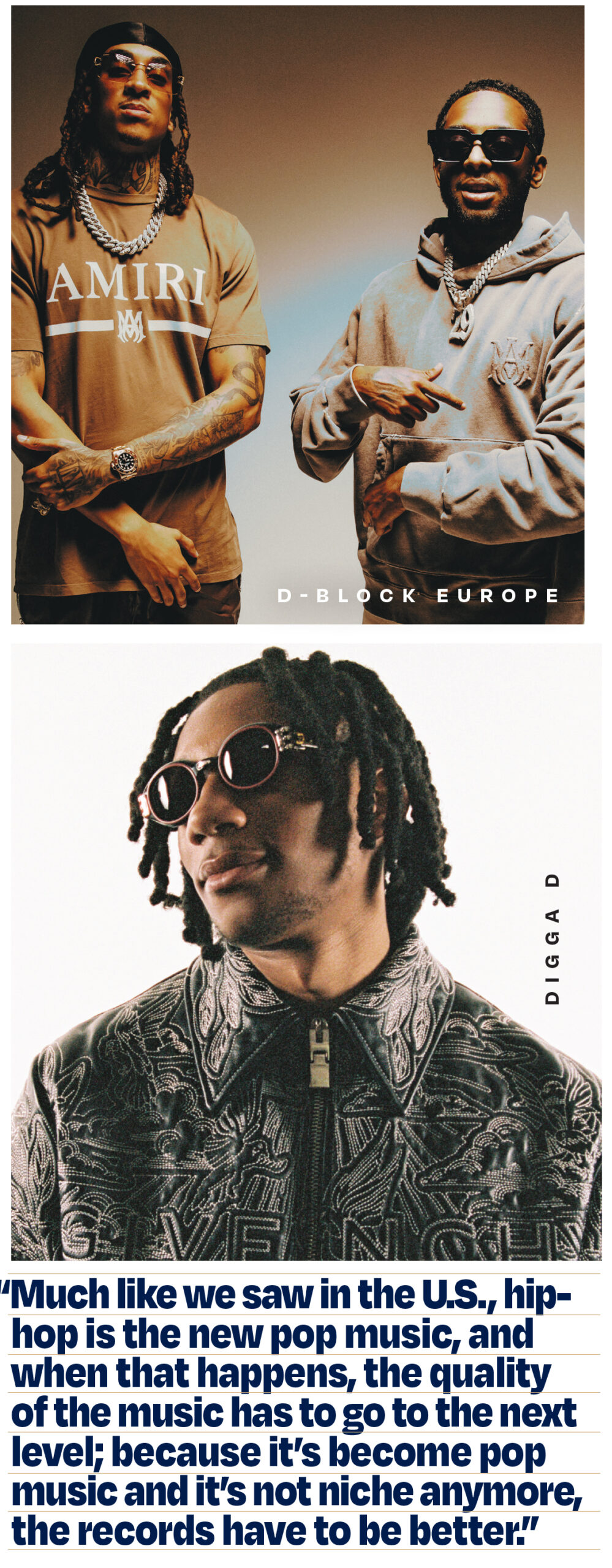

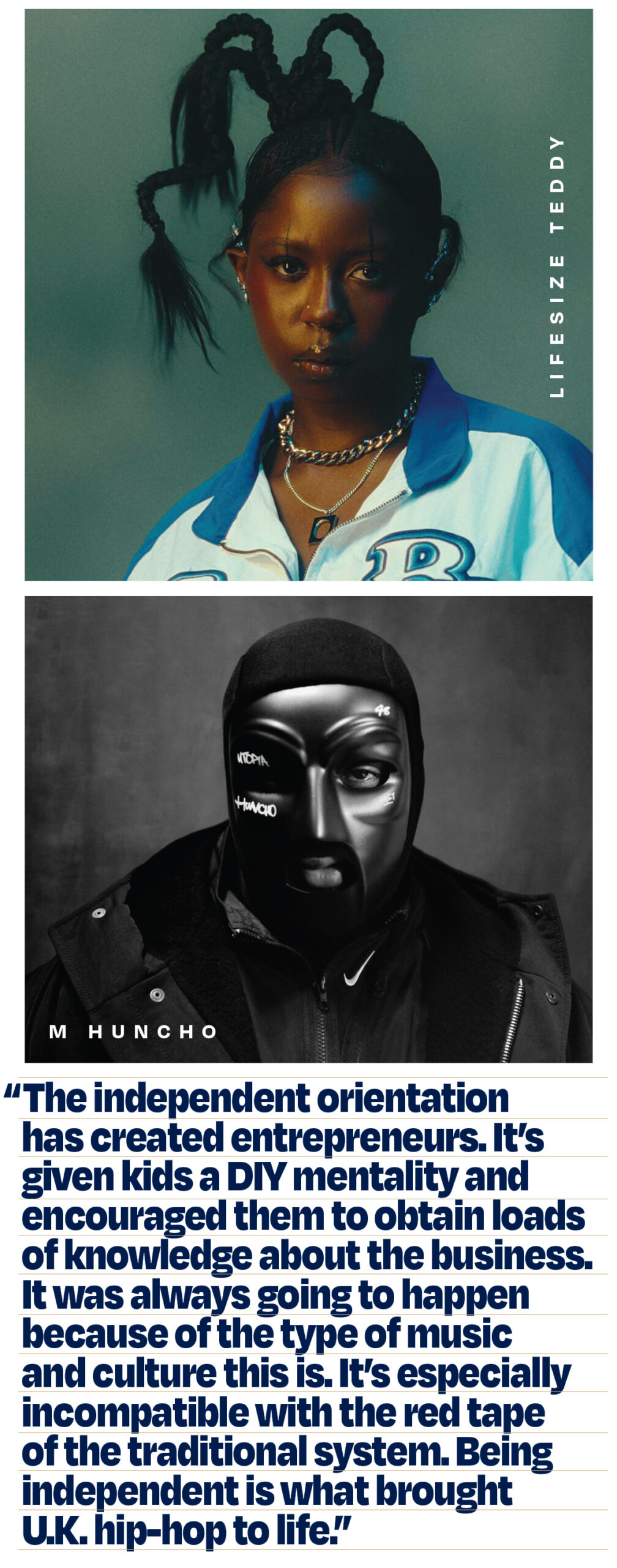

Colin Batsa presides over EGA Distro, which has had Top 10 U.K. albums with D-Block Europe, Digga D and M Huncho. Rapper K-Trap, singer Sharna Bass and new signings Lifesize Teddy and Skrapz complete its roster. Virgin Music Group is an investor and minority partner in EGA, co-founded in 2010 with Victor Omos; Charley Snook later became a partner. Prior to launching the company, Batsa worked for Island Records, Caroline International and Virgin Music Group, where he mounted Rema’s global hit, 2022’s “Calm Down,” and top-selling albums by D-Block Europe and Digga D.

What’s your take on the current condition of the British hip-hop market?

It’s in a healthy space in terms of Central Cee being, arguably, the hottest rapper in the world―“Sprinter” was the biggest rap song in the world. We’ve never had that before. It’s doing great on a global level, best we’ve ever had. But much like we saw in the U.S., hip-hop is the new pop music, and when that happens, the quality of the music has to go to the next level; because it’s become pop music and it’s not niche anymore, the records have to be better.

It’s in a healthy space in terms of Central Cee being, arguably, the hottest rapper in the world―“Sprinter” was the biggest rap song in the world. We’ve never had that before. It’s doing great on a global level, best we’ve ever had. But much like we saw in the U.S., hip-hop is the new pop music, and when that happens, the quality of the music has to go to the next level; because it’s become pop music and it’s not niche anymore, the records have to be better.

At the moment, there’s a gap between the performance of superstars and that of the average act. A couple of years ago, a pretty good rap song could get into the Top 40 or Top 100. Now, unless you have a hit, it’s not even going into the Top 100. Some of the stuff is doing exceptionally well and going around the world, but most of it, internally and at the grassroots level, is not doing well; it’s suffering. There’s no in-between.

In America, a similar thing happened with the rap market because it got so saturated. The music loses its essence. So we have to step up now and make stronger music and stronger moves. There needs to be a bunch of new kids who come along and excite us again.

How do you improve the quality of the music?

Artist development. And I do think it’s happening. EGA, 0207 Def Jam and Neighbourhood, for instance, are dedicated to the music and doing really well at the highest level. Kids are signing to these more hip-hop-specific labels that probably understand the genre and the music more than the majors, and people are building their companies based on these acts. The artists are not just signed to a major where they’re one of 100; they’re signed to a smaller label that’s banking its future on them, so there’s more investment in, and time for, artist development.

What impact do you think this independent orientation has had on the music and the culture?

What impact do you think this independent orientation has had on the music and the culture?

It has been amazing. It’s created entrepreneurs. It’s given a lot of kids a DIY mentality and encouraged them to obtain loads of knowledge about the business. It’s also helped them find a career path―an artist’s friend can be their manager, so the friend also has a career and can grow. It was always going to happen because of the type of music and culture this is. It’s especially incompatible with the red tape you can find at the major labels, in the traditional system. Being independent is what brought U.K. hip-hop to life.

How does a distributor like EGA compete with major-label deals?

I think the majors are more worried about me than I’m worried about them, especially in hip-hop. You used to think you couldn’t be successful abroad unless you were signed to a major label. One of my acts, Rema, recently had the biggest song in the world and we’ve done that independently. Central Cee has had international records independently. RAYE went to The Orchard and she had a global hit. The playing field is quite equal.

I’m competing by not paying as big as the majors, but I’m not paying too badly. Artists get a higher percentage of royalties and we offer speed. Artists want to put their music on TikTok or YouTube in two weeks and a major can’t do that, but we can. A lot of artists don’t like optical marketing, which is all about something looking good but not meaning anything. I don’t see how putting a logo on a tower is going to produce a stream or sell an album. The smaller companies do actual marketing; we’re driving people to the streaming sites, to pre-orders, and I think a lot of artists prefer that. I’m not anti-label, but I am pro-artist. Some artists should be on a major label, especially if it’s pop music and you want a lot of investment in your artistry, in your clothes, but I think for Black music in general, and for hip-hop, it needs to be independent and it needs to be with smaller labels.

What kind of marketing strategies do you deploy?

We’re identifying the artist’s strengths and trying to be as creative as possible. Digga D wanted to do a documentary with his album, so we turned that documentary into a cinema activation. We had it in Everyman Cinemas and there was a premiere. It was something different; nobody’s ever launched an album with the premiere of a documentary. And we’re creating amazing relationships with DSPs and social-media platforms. In the past, if you were a radio plugger, you’d take the DJ out to eat; nowadays, it’s about who owns TikTok―let’s take him out. So it’s about being as creative as possible but also homing in on getting as much love from DSPs as possible, having your social media be as engaging as possible and driving the pre-order.

Do you have the power to make global superstars with longevity?

Do you have the power to make global superstars with longevity?

I believe so, but it’s really not up to us; it’s up to the people. Music is so democratic at the moment—the people decide who the biggest is. Bad Bunny, who was the biggest streamer last year, is distributed by The Orchard. He’s independent. The biggest song for Universal U.K. last year was Rema’s “Calm Down,” which is also independent. But being independent or signed to a major is irrelevant. If the people want you, they want you, and no one can stop that.

What impact does your relationship with Universal have on what you do?

They give me global muscle. They understand entrepreneurship and I believe that, out of the three majors, they are the best company when it comes to entrepreneurs. They have a firm understanding of the music, global reach and they allow me to be me. They are so strong around the world and so powerful in each territory that it makes me like a major independent even though I’m a small independent. It’s definitely been very beneficial. They’ve allowed me to compete with some of the bigger companies in the world.

How do you see British hip-hop evolving?

There will be more businesses that come from it and more labels dedicated to the music. There will be stronger superstars and great executives. I think it’s really growing and in a great place; we just have to even up that gap, but I do believe it’s going to evolve. There are going to be more superstars on the same playing field as the pop and rock stars. It’s a bright future, but we can’t take that for granted and need to fix a bit of a mess backstage.

What future do you see for music distribution?

Technologically, there are going to be more solutions to make things faster, more automated and better accounted for. A lot of people are putting time and effort into creating better solutions for distribution services, but the future of distribution is label services. I think some distributors will become an amalgamation of label, indie and distro. I do label services and I don’t do anything different from major labels. And because I do label services really well―in terms of digital, marketing and international―a lot of artists are now giving me licenses for longer terms because they believe in what we’re doing. The future is that a lot of us are going to become service companies doing more than just distro. We and EMPIRE do label deals too, and I feel that’s where it’s going.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.