Lenny Kravitz does not blend in. We’re sitting in Bemelmans, the iconic piano bar at the Upper East Side’s historic Carlyle Hotel. Here, things are done properly. Have been since 1947. Waiters wear white coats. Cocktails, served exclusively in etched crystal glasses, arrive on silver trays. Fancy little bowls full of fancy little bar snacks adorn the tables. Murals by Ludwig Bemelmans—of the Madeline children’s book fame—decorate the walls. And some of the country’s most celebrated jazz pianists still play the black and whites nightly. It is a place completely synonymous with old-school New York City glamour. It’s also maybe the last place you’d expect to spot a certified rock god during daylight hours.

But this is where Kravitz wanted to meet, so here we are. It’s 3:00 P.M. on a very rainy Yom Kippur; the remnants of Tropical Storm Ophelia are battering Manhattan outside, and the sparser-than-usual crowd is almost entirely drinking martinis. Kravitz, who is staying at his daughter’s Brooklyn apartment while she’s holed up in his Paris home, looks like he beamed in straight from 1975. Tailored brown-leather jacket, turtleneck, flared trousers. His signature locks are pulled half back, and gold rings wrap around a few of his fingers. He orders a hot green tea.

Surprisingly enough, Kravitz is right at home at the Carlyle. This is where his mom, Roxie Roker, then an assistant at NBC and an aspiring actress, asked Bobby Short, the fabled cabaret singer who headlined here for decades, if she should accept the marriage proposal of a news producer who worked in her building named Sy Kravitz. (Replied Short: “I don’t see anyone else asking!”) When Lenny’s classmates were with sitters on Saturday nights, Short visited him and his parents at their table between sets. He met Andy Warhol here many years later at a party for Bret Easton Ellis. Kravitz even hosted his dad’s final birthday party here in the early 2000s. “This place is all over my life,” he says plainly.

Besides, has Kravitz ever blended in? The only son of Roxie and Sy, he is equal parts his mother, a Black woman of Bahamian descent, and his white, Jewish father, whose family came to America from Kyiv before Sy was born. Growing up biracial in the sixties and seventies, Kravitz stuck out as much in the largely white East Eighties of Manhattan as he did in the primarily Black Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, where he lived during the week with his maternal grandparents while his parents worked in the city. It wasn’t a problem.

“I was comfortable,” says the man who, decades later, would push the boundaries of rock and fashion—the very definition of cool, even—into new frontiers. “I dug that.”

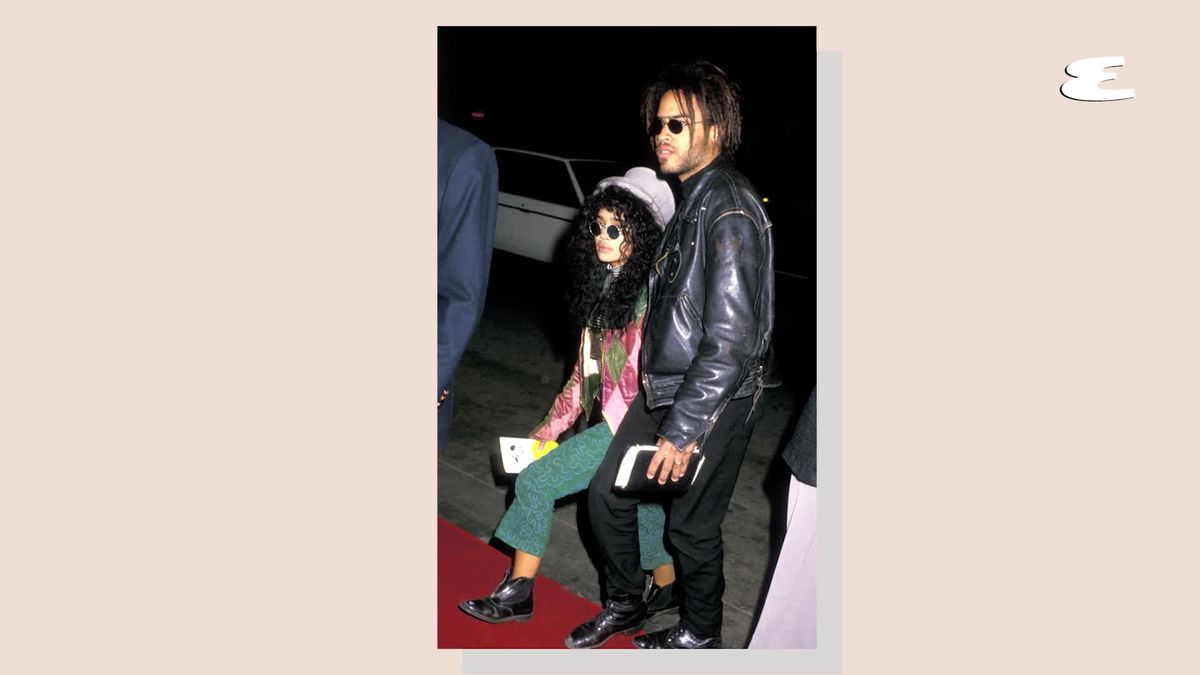

Colson Whitehead once wrote that everyone’s New York is the New York they first arrive in, that they begin building their own private skyline the moment they lay eyes on the city. Kravitz, fifty-nine, has arrived in Manhattan a few times, always welcomed by a different city. His parents had an apartment around the corner from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, on Eighty-second Street. He spent his middle and high school years in Los Angeles but returned in the late eighties when he moved in with his girlfriend, Lisa Bonet—Denise Huxtable herself. And a decade and a half later, after trying out both New Orleans and Miami, he came back with his and Bonet’s daughter, a then-teenage Zoë Kravitz.

Kravitz misses all of his past lives in New York for different reasons. But as Whitehead predicted, his true New York is the one that sitting here in Bemelmans brings him back to. The Upper East Side. After all, he says, it changes more slowly than perhaps any other neighborhood in the city. Lobel’s, his mother’s favorite butcher shop, remains around the corner from their old apartment. Their preferred café, E.A.T., is still just down the street. Of course, some things inevitably change. And like any New Yorker, Kravitz delights in recalling what a current building used to be. Example: The Nectar diner on Eighty-second and Madison was once the Copper Lantern, where young Lenny first learned to tie his shoes.

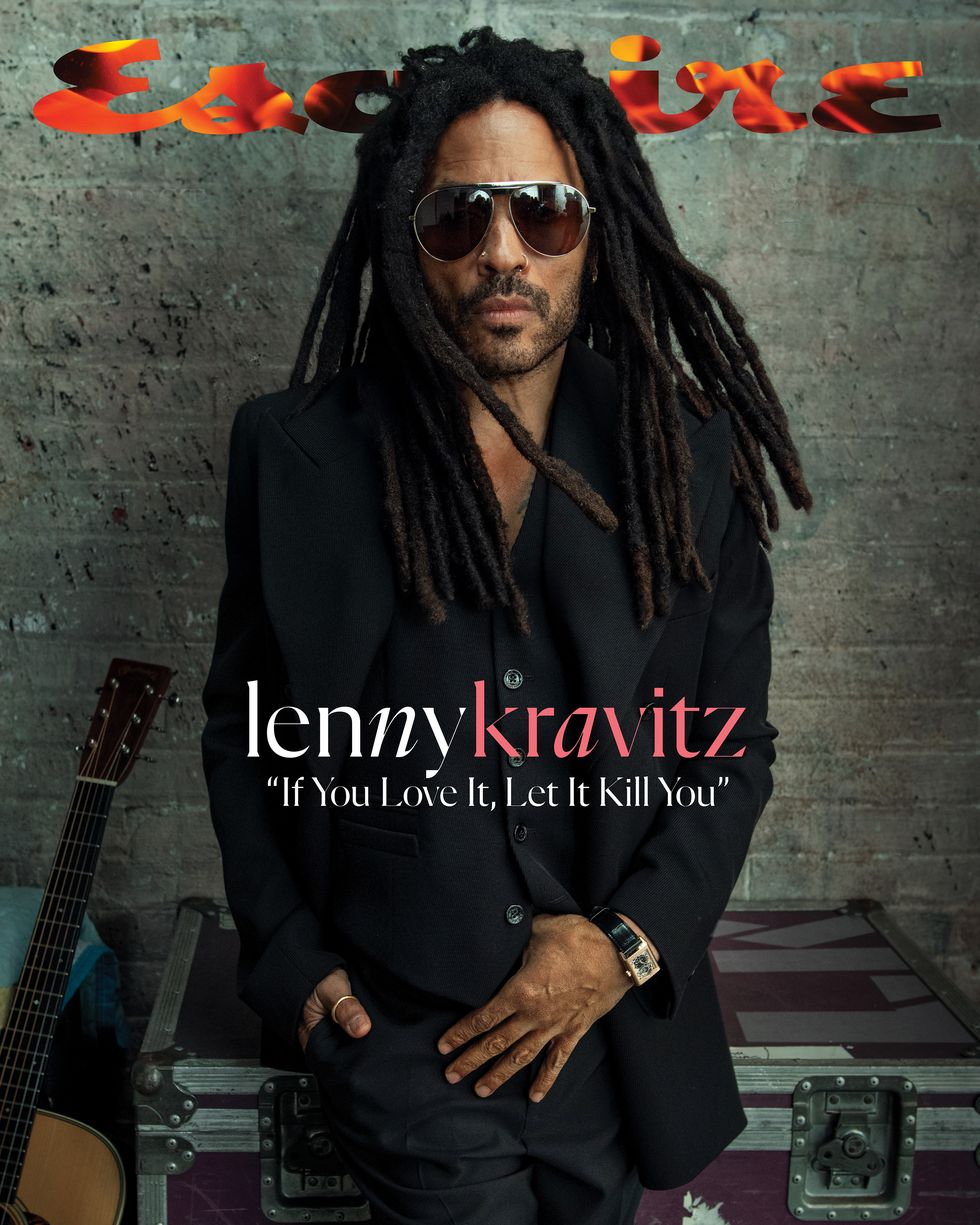

He rarely comes to town just to visit. It’s almost always for work, and this trip is no exception. When he’s in New York, he is typically in a constant state of motion—though you get the sense that Kravitz himself wouldn’t use the word work to describe his various ventures in interior design, philanthropy, and spirits. He’s just as busy as ever this week, but it’s in service of his first love. For the first time since 2018, he is on the verge of releasing new music: Blue Electric Light, a buoyant, occasionally blistering electro-funk collection, drops March 15.

Kravitz has long favored first-person storytelling in song, but on two of his recent releases he mainly looked outward. Black and White America (2011), brimming with Obama-era optimism, imagines life in the U. S. A. beyond the racial divide; Raise Vibration (2018) bears witness to the comedown, urging positivity as the necessary response to the divisive Trump tenure. With this new set, Kravitz’s attention has returned inward. His testimony to the power of self-love and personal evolution is searingly specific and at times downright anthemic. It also—and this is important—flat out cooks musically.

The arrival of Blue Electric Light marks the end of the longest span Kravitz has gone between albums since his 1989 debut, Let Love Rule. Ten records followed his first one, each dropping at a steady clip. The pandemic shutdown had a lot to do with the atypical five-year lag time. But Kravitz credits the isolation imposed by Covid with triggering a period of powerful creativity and reflection.

Kravitz showed up at his Bahamas home in March 2020 with enough clothes for a weekend. Two years into a three-year tour at the time, he thought he’d stop at the beach for a few days to recharge between runs of shows. But then the next leg got canceled. And the next. Kravitz stayed for the better part of the next two and a half years.

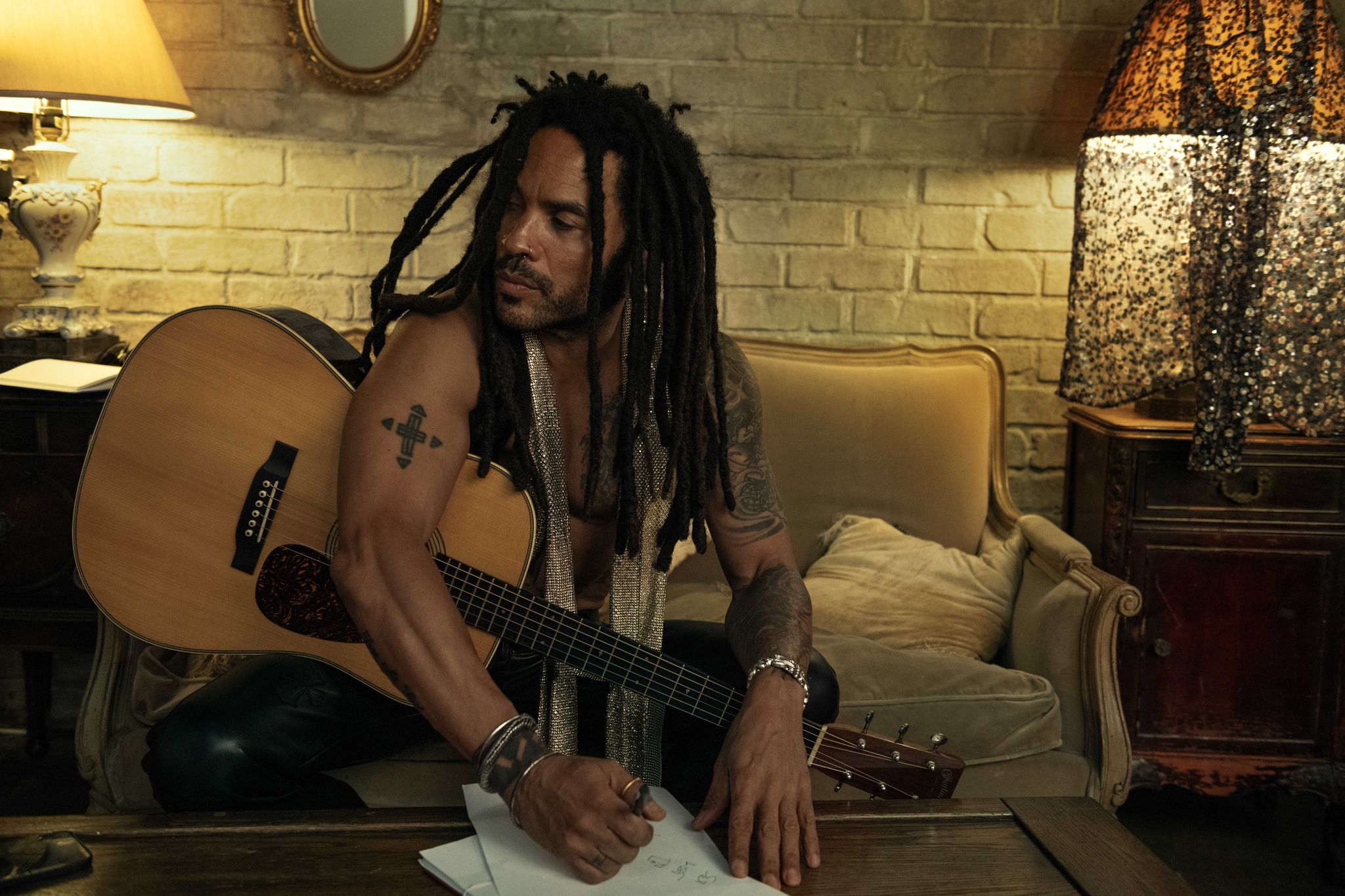

Musical inspiration finds him on Eleuthera, the island he calls home. He bought thirty acres when he signed his first record deal and for a long time lived in an Airstream on his own beach. He still has it, though he’s since built a proper house elsewhere on the property. There’s a garden out back where he grows his own fruits and vegetables. A studio nearby. “Shoes go out the window,” he says. “There’s no keys. No wallets. No money. You start to go with nature.” Kravitz is normally a night owl, going to bed around 5:00 in the morning and waking up at noon, but after a certain amount of time there he resets. Heads to bed shortly after dark, wakes up early.

During the longest stretch of stillness—of staying in one place—in his adult life, music poured out. At times he barely slept at all. Waking up at all hours, hearing melodies in his head, and racing to get them down. He had three separate albums in progress. It was chaotic and occasionally hard to organize. Harder still to finish. But as the world began to open and live shows returned to calendars, Kravitz tinkered away in the studio. Testing different arrangements, dialing up the drums, lowering the vocals. Mixing songs and then mixing them again—“a thousand times,” he says. “I kept polishing.”

He expects we’ll hear the two other sets, both mostly completed, someday. But the music on Blue Electric Light is what he’s feeling now, he says. “This one spoke to me.” He’ll devote the next six months to promotion, and then the next couple years to a world tour. He’s ready for all of that. Hungry, in fact. “This one has to come out.”

It feels like Lenny Kravitz has been the epitome of cool forever. But when Let Love Rule debuted, it did so to a lukewarm response stateside. You could argue that people didn’t get it. Didn’t get him. As hip-hop was exploding in popularity, here was a twenty-four-year-old Black man from New York making rock music using vintage recording techniques and old-as-hell equipment. At the same time, the rock charts he was trying to hit—almost wholly white in makeup then—were rattling with pumped-up LPs from the likes of Aerosmith and Mötley Crüe. Raw and insular, at times even delicate, there was nothing else like his sound gaining traction.

“I look at him as someone who stuck to their guns,” says longtime friend and occasional collaborator Jay-Z. “This is what I like. This is the type of music I like to create.” He adds, “You always applaud that: someone who stays and does what they do and doesn’t follow trends. Someone who has that confidence in what they’re doing is very rare.” Europe was different. His crowds were growing faster there. So he toured and toured and toured abroad. Then he dropped his second album, 1991’s Mama Said. Equal parts gritty and tender and musically steeped in the sixties, it defied trends and expectations. The set went platinum, and his rock ’n’ roll peers were suddenly curious. Bruce Springsteen came to a show and became a friend. Prince, too. And when the Purple One met Kravitz, he told him in no uncertain terms, “We’re going to be brothers.”

Mick Jagger, a personal hero of Kravitz’s, even wanted to hang out. Kravitz was floored. Jagger came backstage before a show and, spur of the moment, they decided they should sing together that night, live. Learned the song just before the houselights dimmed. Afterward, Jagger went back to Kravitz’s hotel and the two spent the night talking and toking up. “I saved that roach for like ten years,” Kravitz says. What happened to it then? “I was out of weed and smoked it,” he replies, laughing.

But even after his next two albums—Are You Gonna Go My Way (1993), whose title track became a pop-culture statement, and Circus (1995)—did better and then better again, cracking the top twenty and then the top ten of the all-genre Billboard 200 albums chart, Kravitz struggled to be taken seriously by the rock-critic establishment. Maybe it wasn’t that they didn’t get it. Maybe it was that they didn’t want him to have it.

This article appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of Esquire

Subscribe

“There was this one article that, at that time, said, ‘If Lenny Kravitz were white, he would be the next savior of rock ’n’ roll,’ ” he recalls. Instead, reviews dragged him for relying too heavily on his influences. Accused him of lacking originality. Of doing a Led Zeppelin impression, as if Zeppelin never riffed off anybody. “I got a lot of negativity thrown at me by all these older white men who weren’t going to let me have that position,” he says calmly.

They still aren’t. Forty million records sold. Four Best Male Rock Vocal Performance Grammys—in a row. An MTV Video Award from the time MTV Video Awards still mattered. Concerts at the biggest venues on the planet. The true sign of relevance in this century, he’s even an annual meme; photos of Kravitz in his bewilderingly oversize scarf flood the Internet on the first day of fall each year.

“There would be no Tyler, the Creator without Lenny Kravitz,” says Jay-Z. “We need those moments of inspiration. That pushes creativity and opens up lanes for others.”

Kravitz says he isn’t bothered by the lack of respect he’s received from critical institutions. “It was discouraging at times,” he’ll allow. But he doesn’t think much about it now. “I’m good. Intact—happy, healthy, focused, with still so much to do.” That’s more important.

But ask him if he’s aware of recent racist and misogynistic comments from Rolling Stone founder and former editor in chief Jann Wenner and Kravitz sits up. “Very much so,” he says. For those catching up: While promoting his new book, The Masters, touted as a “visit to the Mount Olympus of rock,” Wenner said in an interview with The New York Times that the reason all seven of his subjects are white men is that there aren’t any women or artists of color “articulate enough” on the subject to speak about it. When the Times gave him an opportunity to rephrase what he said, Wenner doubled down.

“It’s very disappointing,” Kravitz says, “and sad. I’ve known Jann since 1987.” Met Wenner before he even made his first record, when Bonet was on the cover of the Hot Issue, pregnant with Zoë. The two men became friendly. “I’ve been to his house. In his life.” He’s had Wenner’s ex-wife and their children (his son Gus is the current CEO of Rolling Stone) down to the Bahamas. Now it’s Kravitz’s turn to double down: “I was disappointed. I was very disappointed.”

It’s not just the personal connection that hurts. “The statement alone, even if you just heard about the man yesterday, was appalling and embarrassing,” Kravitz says. “And just wrong.”

Those old reviews make a bit more sense when you read those comments, I suggest.

His one-word answer: “Yes.”

Kravitz is more mystified, though, by how he’s been treated by Black entertainment and culture outlets. Take Vibe magazine, which featured a who’s who of Black artists in its pages when it began publishing in 1993 but waited almost a decade to put Kravitz on the cover. And it wasn’t just Vibe. “To this day, I have not been invited to a BET thing or a Source Awards thing,” he says. “And it’s like, here is a Black artist who has reintroduced many Black art forms, who has broken down barriers—just like those that came before me broke down. That is positive. And they don’t have anything to say about it?”

He’s got a point. And it’s not as if he has scandals hanging over him. Punch “Lenny Kravitz controversy” into the search engine of your choice and all that comes up is a wardrobe malfunction involving a pair of split leather pants that was out of his control. But Kravitz can’t make sense of the reception he’s received over the years—he doesn’t understand why his success “is not celebrated by the folks who run those publications or organizations. I have been that dream and example of what a Black artist can do.”

Still, he doesn’t want to complain. Life is too beautiful. “I’m not here for the accolades,” he says after a pause. “I’m here for the experience.”

For all its gilded trappings, fame can be punishingly isolating. Yet famous people are so rarely alone. For a long time, Kravitz was no exception. His homes were busy and loud. Teeming with bandmates, revelers, and women. Groupies and neighbors. At one point, even a professional joint roller whom Kravitz used to keep in his employ. People claiming to be his friend, to love him. “Who are these people?” his mom used to ask. Sounds like she had good reason: On one visit to his loft on Broome Street, in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood, following the release of Mama Said, she sat down to eat with her son at the dining-room table. Except in a classic case of famous-man feng shui, the dining-room table was right next to the pool table, and there was a guy sleeping under it. He popped up at the commotion, and Roker couldn’t believe her eyes. “My mom looked up and said, ‘And your name is?’ ”

His house in Miami—the first one, though he doesn’t own any property there these days—was basically a recording studio and a nightclub. “It was absolutely insane,” his daughter, Zoë, says, referring to the period right after she arrived in the Sunshine State at age eleven to live with Kravitz for the first time in her life. (He and Bonet split in 1991 and divorced in 1993.) “It was like living in a mall or an airport, where people are just constantly coming in and out.”

Eventually, though, it became clear that a lot of those friends weren’t actually friends. They didn’t love him. “I got burned,” says Kravitz. “Completely. I put it all out there, and I put it all out there in a way for people to take advantage of it. I was an empty vessel.”

Zoë shares a story about an incident that wasn’t funny at the time but that she laughs about now. When the actress was fourteen or fifteen, she and a friend descended into the kitchen to find a woman they’d never seen at the table, eating a slice of pie. No big deal; there were always people she didn’t know in the house. But when her dad came home and asked to be introduced to Zoë’s other friend, they both froze. “She ended up being some unwell person who found their way into the house,” Zoë recalls. “We realized, we need to button this up a little bit.”

But clearing ranks was unnatural for Kravitz. “Saying no is very difficult for me,” he explains. “I was like that from childhood. My mom used to call me the Pied Piper. I’d bring everybody home. Just met them a few hours ago? I bring them home. I love people. I always have loved people.”

And perhaps it wasn’t just his personality type, he considers, but also the color of his skin. “Being Black in America at that time,” he says, referencing his childhood in the seventies, “everybody’s sticking together. Everybody’s helping each other. There’s always an extra seat at the table. There’s always extra food.” You take care of your people.

By the time Kravitz decided to tighten his circle, he had been famous—superfamous—for more than a decade. The toll was obvious. There were stretches on tour when he would get back from a show, close the blinds, and sleep until it was time to do the next one. Spend even just a little time with Kravitz and it’s obvious that he is naturally suited to having fun. But he wasn’t then, and he hadn’t been for a while. When Robert Plant, supporting a solo album, opened for Kravitz in the nineties, one evening included the Led Zeppelin frontman yelling at his headliner for taking his concerts too seriously. “You need to start having a good time with this!” Kravitz bellows, recalling the scolding. A few years later, on her deathbed, Roker offered a warning by way of an admission when she told her only son, “I wish I hadn’t taken it all so seriously.”

Change wouldn’t come for several more years. Kravitz had become too closed off. And he struggled with feelings of depression. “There were times when I had to fight that darkness,” he says now. But the people who loved him kept pushing. “I used to have to really confront him,” says Zoë. Her message: “ ‘I don’t see you very often. Get rid of all these people.’ ”

As his home life got quieter, Kravitz evolved, blossomed. “That’s what’s allowed all this growth, not only as a person but as an artist,” says Zoë. “He’s taken the time. It’s the quiet moments when you have all these little epiphanies—these emotional shifts. He’s made space for that.” His communication, she says, improved along with his outlook. Kravitz echoes the sentiment: “Now I’m in a place where I just want to embrace the light.”

His inner circle agrees. “I don’t know what the definition of a great friend is,” says Denzel Washington, “but I am sure there is a picture of Lenny Kravitz next to the words.” Washington and Kravitz became friends so long ago that any details regarding their initial meeting are outside of memory’s reach. But the actor, famous for roles in Training Day and American Gangster, does remember hearing Kravitz’s music before they fell in with each other, adding with a laugh, “I don’t know if I bought any of it—just being honest!” The two men raised their kids alongside each other, and now they all gather at Kravitz’s home in the Bahamas every year. What’s better, though, says Washington, is that their greatest memories lie ahead. “The best thing I can say about our friendship is that it’s still happening.”

Jay-Z can’t remember how he and Kravitz met either, come to think of it. Been too long. But they share a group of friends and get together when they can. Over the summer, it was in Paris, for Beyoncé’s concert. “That was a great night,” the rapper recalls of seeing his wife’s show with close friends. Went out, celebrated. Went out some more. Sang “Happy Birthday” to one of the people they were with and to Kravitz, who hadn’t even revealed it was his birthday. “B in Paris was super special,” Jay-Z says by way of explanation.

These days, Kravitz splits most of his time between his homes in Paris and the Bahamas, though he also owns a farm in the Brazilian highlands. In the French capital, he surrounds himself with a small group of locals. A few Americans. Many Africans. They go out to eat. See concerts. Kravitz’s French isn’t great. “I get by,” he says. He loves the ballet and the opera. The fashion. “And just feeling the energy of the city.”

When he wakes up each afternoon, he figures out what he wants to create that day. Often, it’s music. Other times, it’s design work with his firm, Kravitz Design, which has transformed a slew of high-end homes as well as a Manhattan apartment complex since Kravitz started the business in 2003. It may be photography—Kravitz’s pictures have been shown in several exhibitions, and he shot an ad campaign for Dom Pérignon. Maybe it’s to do with movies. Kravitz has acted many times (and quite well) over the course of his career, but his most recent work in Hollywood was providing a new song for the soundtrack of the Netflix original movie Rustin, “Road to Freedom.” Or it could have something to do with Nocheluna, his new liquor brand, which brings one of Mexico’s more curious spirits, sotol, to the international market.

Whatever it is, it’s not work to him. “It’s just living.”

I’ll confess something: I’ve always been a little bit fascinated by the impossibly attractive, somehow even more talented blended family that still connects Lisa Bonet and Lenny Kravitz. The two dated young, married young, and became parents young. Bonet, then a household name through her role on The Cosby Show, was just twenty-one when Zoë was born; Kravitz was twenty-four. He credits Bonet and their relationship with finally unlocking his creative vision. Before they met, he’d been trying on alter egos like “Romeo Blue,” wearing blue contacts with his hair in Prince-esque Jheri curls, and considering a record deal that would have made him the frontman for an all-Black version of Duran Duran. “I was not sold on me.”

Let Love Rule is, by and large, an album about falling in love. But Kravitz and Bonet’s romance didn’t survive more than the first few years of his ascent—the despair Kravitz felt as it began to unravel is all over Mama Said—and the years after required a lot of work for them to be on an even keel. (Zoë stayed with her mother in Topanga, California, away from the spotlight.) They’re good now, and have been for decades. In 2005, Bonet began dating actor Jason Momoa, and Kravitz took him in as well. He became his brother—and “Uncle Lenny” to the two kids Momoa and Bonet would have together in their near-two-decade relationship. Kravitz doesn’t really get the public interest in his healthy relationship with Bonet. Why is everyone so curious about how it all works? He sees posts with long captions about how they’re an inspiration—how this is the way “it should be” between exes—and it’s not as if he’s not flattered. But for Kravitz, it’s simple: It’s family. Even when it wasn’t working, he knew one day it would. It had to. “I wouldn’t think of it as this heroic feat,” he says. “This is just normal to me.”

Still true today, as that family has recently entered another new phase. Bonet and Momoa split in early 2022, after seventeen years together—but according to Kravitz, the bond between each, while different, is just as important. Case in point: In a crisis of parenthood, Kravitz was stuck in the Bahamas and missed the New York premiere of The Batman, starring Zoë, last year. Bonet couldn’t make it either. “ ‘I got you,’ ” Momoa assured Kravitz. “ ‘I’m going to this one. I’ll be there.’ ” And he was, bringing Zoë’s half siblings along with him. Tabloids furiously speculated about whether Momoa and Bonet were reuniting, but they missed the point. Family shows up. “It was beautiful,” Kravitz says.

He has no trouble talking about his family. His ex. Her ex. His mom and the life she opened up for him. Sitting on Duke Ellington’s lap at the Rainbow Room in Manhattan, being serenaded with “Happy Birthday” as he turned six. Bonding over music with Miles Davis, then married to Kravitz’s godmother, Cicely Tyson. Wasting away an evening right here at the Carlyle, “listening to Bobby.” When he spent all his time in school playing music rather than studying, it was Taj Mahal, the genre-altering American blues singer, who sat his father down and told him to let Lenny run at it.

Kravitz provided his daughter with a similarly charmed childhood. But as Zoë decided to pursue acting, instead of delighting her, her background caused her anxiety. And instead of running at it, she ran from it. She even tried changing her last name as she began her career. “I understood it,” says Kravitz, “but I was like, That’s your name.”

Have you been online in the past two years? Okay, great, so you’re familiar with the term “nepo baby” then. Of course, we’re talking about the phenomenon at a moment when, after decades of the entertainment industry being full of sons and daughters and nephews and nieces and granddaughters and grandsons—you get it—of other famous people, the Internet has finally had enough.

Timelines are filled with accusations of how nepo babies get better treatment. The term has become a slur. When New York magazine did a story on the subject, it included a picture of Zoë on the cover. “I don’t understand that whole thing,” Kravitz says, “if”—and it’s a big if‚ he admits—“you are good at what you do.”

It’s been a while since Kravitz has had a serious partner. He’s been one half of many an It Couple over the years—after Bonet, he dated singer and model Vanessa Paradis for five years. He popped the question to Brazilian supermodel Adriana Lima in the early 2000s and then got engaged to Nicole Kidman not long after his previous engagement fell apart. He dated Lima’s countrymate and fellow lingerie model Barbara Fialho in the 2010s. From the outside, it looked pretty cool. But on the inside, as each relationship failed, Kravitz struggled. He felt cursed.

Growing up, Kravitz was especially close to his mother. She was strict but caring. Worked tirelessly—first at NBC, then in the New York theater community. She became a household name when she landed a landmark role as part of television’s first onscreen interracial couple on The Jeffersons. When Roker booked that gig, only she and her son moved to L. A. at first. And during the show’s first season, they slept next to each other on his godmother’s pullout couch. Roker took two buses to work, spending hours each day in transit. At home, once the show was renewed and her husband had relocated, the family living under one roof again, Roker still did all the cleaning, using her off-hours to scrub floors and toilets.

Roker was humble, but her unwillingness to show off the life she’d earned for her family was rooted elsewhere. Sy had difficulty finding his professional footing out west, trying on a variety of showbiz roles: manager, agent, producer. Nothing stuck. Kravitz watched his mother make herself smaller so that her husband might feel bigger. He also floundered under his father’s rule. Sy had served in the Army, and for him, there was only one way of doing anything. When Kravitz was sixteen, the tension boiled over and he moved out. He would never live with his parents again, spending the next few years bouncing between friends’ couches and rental cars.

At nineteen, Kravitz discovered that his father was having an affair. He begged his mother to fly him to the Bahamas, where she was visiting her own father, so he could break the news in person. Except Roker wasn’t surprised. Sy had been cheating on her throughout their marriage, she revealed. They would stay together for a short while longer—until Roker learned how much money her husband had siphoned off for his mistresses and gambling. As Sy packed up and prepared to leave, Roker asked him if he had anything to say to their son, who was there to witness his departure. “You’ll do it too,” he spat.

There’s a saying in the Bahamas for a moment like that: Don’t put mouth on me. “In the spiritual world, it’s called a word curse,” Kravitz says across our table at Bemelmans. “It goes back to anything in the Bible where God spoke everything before it was done. ‘Let there be light.’ The light just wasn’t there! He spoke it into existence.”

Kravitz felt that his father spoke something into existence for him; Sy’s words haunted him for years. “I felt it when he said it, but the shock waves lasted decades and got stronger and stronger and stronger.”

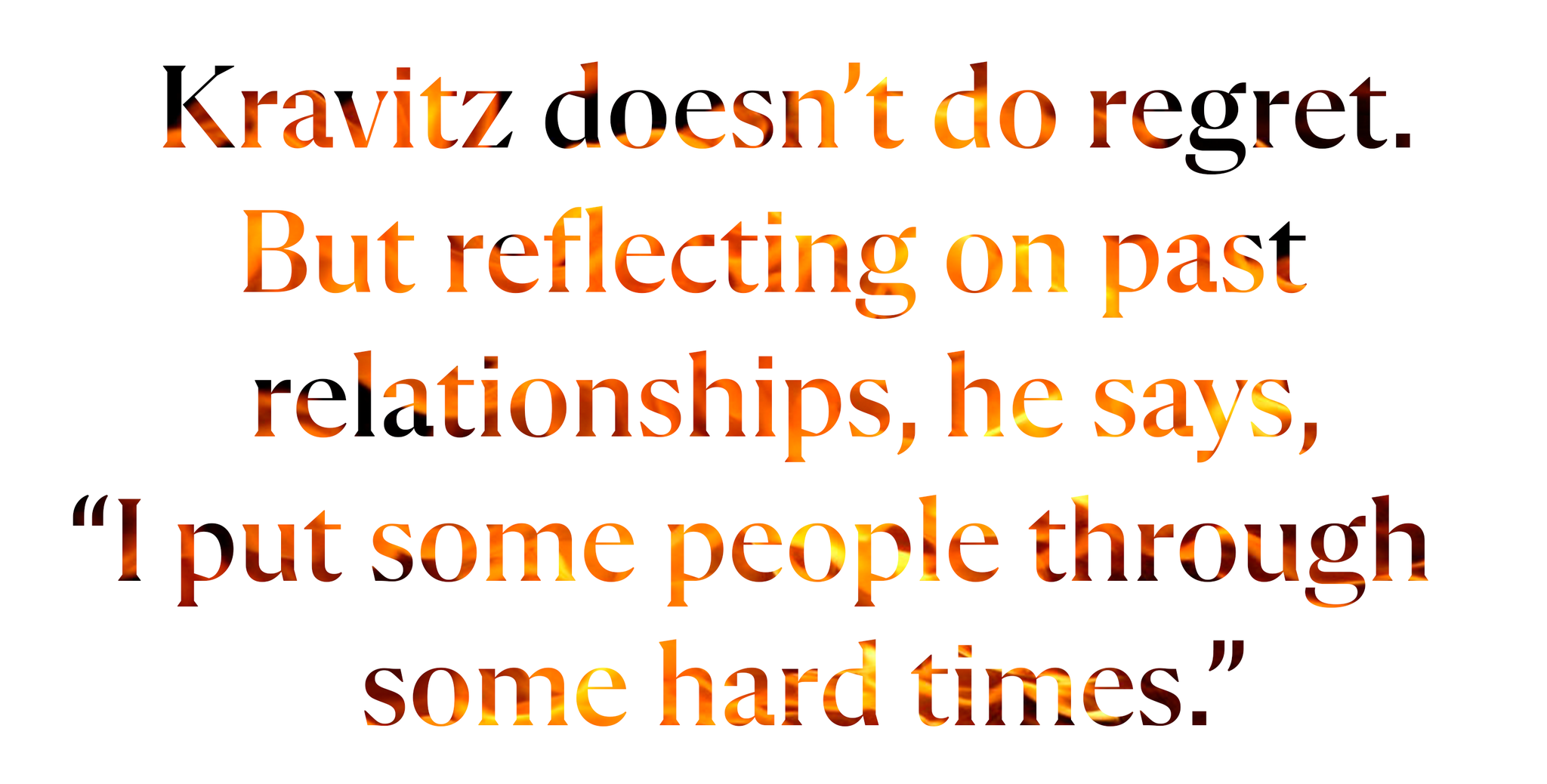

He did indeed have trouble staying faithful in his romantic relationships (“I won’t lie to you,” he says alongside the admission, hands folded in front of him) and with “being confident that this is the person for me, always thinking something else may be better.” That’s all worked itself out now. “It was hardcore.” Took years. More than he would have liked, though he doesn’t do regret; those moments, he says, are “part of the journey.” Still, he certainly sounds sorry when he recalls what his own partners went through. “I put some people through some hard times.”

Kravitz has come close to marriage a couple times since his split with Bonet. “The desire has always been there,” he says, accounting for the near misses. “The tools in which to do so have not always been there.” He’s currently single, but he’d get married again. He wants to, actually. “Absolutely. I’ve grown enough. I’ve become stronger. I’ve become more disciplined. I’ve become more open to be able to do so. But it’s been a very difficult thing for me to figure out.”

Though he hasn’t come close again, he’s open to having more kids, too. “I could not, and I could,” he explains. “If it doesn’t happen, I’ve done the best with Zoë that I could ever dream to do. If I was with somebody that wanted to have kids, absolutely. A hundred percent.”

As for Kravitz and his own father, they got to a better place before Sy’s death. It didn’t come easy. “There was so much resentment,” Kravitz admits. “So much yearning to be loved by him in a way that I could comprehend.” But Roker urged Kravitz not to ever give up on his pops. “That’s your dad,” she always said. “And you’re going to do what you’re supposed to do.” Honor thy father. No ifs, buts, or unlesses.

As Sy aged, his hardened posture toward his son began to soften. Once, when they were sitting together watching baseball, not really talking at all, Sy turned to Kravitz. “ ‘I can’t believe what you’ve achieved,’ ” he said. Near the end of his life, in the hospital, he apologized to Kravitz as well as to Kravitz’s half sisters. “That was the moment,” says Kravitz. The healing process, for him, finally began.

Still, it’s never enough time, is it? Total forgiveness was still a ways off. “I wish he got to live to when I had grown more,” says Kravitz. “Where I could have loved on him in a deeper way. We would’ve had so much fun if he could have lived to the place where I learned what I needed to learn.”

Kravitz imagines the memories they might’ve shared instead. “In my mind, I dream of all the fun we could have had,” he says. It’s not the same, but it’s enough.

Rock icons are rarely known for moderation, but Kravitz has worked hard to keep any potential vices in check. Hard drugs were never really his thing (though he did famously admit to smoking weed every single day from ages eleven to thirty-five). Drinking wasn’t a problem either. Kravitz is not sober, but he can go months at a time without booze. Sex, while readily available (and sometimes with a person other than his girlfriend), was never something he says he aggressively chased. “I was more motivated by love.”

Much of his approach to sex was formed while he was in high school. “I remember the girls always liking the bad guys,” he says. “And it was like, if I have to act like them to have a girlfriend—I’m not down.” There was also an incident that Kravitz writes about in his excellent 2020 memoir, Let Love Rule. When his parents were out of town, they enlisted a family friend to watch their son, then a teenager. And one night when that man, old enough to be an uncle, had friends over, Kravitz retired to his room to sleep. A woman soon entered, slipped into his bed, and began touching him. It’s a brief passage, but he writes that the incident would affect the way he would view sex from then on. “I wasn’t interested in convincing or coercing women,” he writes about his approach to intimacy going forward. “I’d been coerced myself and didn’t like it.”

I ask if he considers the interaction sexual assault. Kravitz resists the label. “It was an experience and a lesson,” he begins. “Everything doesn’t have to be so . . .” He changes course: “I’m not saying that there aren’t things that deserve to be addressed—maybe somebody would say it should have been addressed and that it was, whatever, but that’s the time it was. I lived, and I learned. I wasn’t traumatized.”

So what can throw Kravitz off-balance? All internal factors, it turns out. As a naturally introspective person, he’s long struggled with overthinking. He is also still prone to darkness and feeling down, he admits. “It could happen tomorrow.” But over the years, he’s been able to shorten the duration of the spells. What used to last days or weeks now takes up only a few hours of his time. Never more than a day. “I won’t let that go overnight,” he says.

The path out is mental and physical. Kravitz believes his intense dedication to his diet and exercise greatly helps him stay positive. It’s not just the actual food he eats, which is mainly vegan and primarily raw, or the specific moves he does in the gym—it’s the discipline to make those decisions. “It’s the sacrifice,” he says, “and then accomplishing the daily goal. When you exercise that, it makes you stronger in all the other ways.”

It’s also spiritual. Ask Kravitz about the roots of his relentless optimism and the answer comes quickly: “my constant faith in God and the power of love.” Though for a time in his youth he considered observing his father’s faith and getting bar mitzvahed, Kravitz experienced a religious conversion in middle school and has accepted the gospel of Jesus Christ ever since. He tried out a few churches in L. A. afterward, but he doesn’t claim an organization as his own now. “For the most part, church is everyday life,” he says. “I wake up in church. And I’m aware of God all day long. I can’t escape it. It’s so powerful to me.”

The LGBTQ+ community has been a huge influence on Kravitz throughout his life. “Not only in fashion and style, because that’s just something on top,” he says, but in deeper ways, too. “They raised me. I was in the street—my choice—and it was the eighties in West Hollywood. It was that time; artists, musicians, hairstylists, and designers, those were the people I was hanging out with. I wanted to be around the creatives, and most of the people I met were from that community.” They took him in and, as he says, “protected me. Educated me. Fed me.”

Kravitz doesn’t deny that organized religion has been awful to the community he loves. They aren’t the only ones who have had the good word weaponized against them, he is quick to remind me. “The Ku Klux Klan themselves were reading out of the Bible,” he says. And as he figures (and history surely supports), “people will always use Jesus Christ to back up something that’s got nothing to do with how Jesus Christ would handle a situation.” That’s a reality that changes his relationship only with church, not God, says Kravitz.

Denzel Washington, the son of a Pentecostal minister and now a self-proclaimed man of God, finds inspiration in Kravitz’s relationship with the divine. “I read the Daily Word every day,” he says. “And the word for today—I tore the piece of paper out, so maybe I was supposed to read some of it to you—is inspire.”

I’ve just asked if he could speak to what role faith plays in his relationship with Kravitz, and Washington reads me the entry in reply: I give thanks for those who have helped me spiritually. As I reflect on those teachers and wise guys who’ve inspired me along my spiritual journey, I prayerfully center each one in the love and light of God, remembering the ways they supported and encouraged me. These radiant souls nurtured my spiritual growth.

“I don’t know if that’s an answer to your question,” he says, “but that’s my answer.”

Lenny Kravitz looks like he just woke up. It’s 1:00 p.m. the following Wednesday, and he’s in Miami. We’re on Zoom, and Kravitz is in bed, wearing a silvery, sheer tank top. He’s there for only a second, as he seems to reconsider his background, quickly moving to the kitchen of wherever he is staying. After a few minutes, he makes an espresso.

When we parted the week before, Kravitz was heading straight to his dentist’s office to discuss plans for their annual dental mission in the Bahamas. The next day, he had a big photo shoot—ours—and then jetted off to Florida to film a new music video. Somewhere along the way, he also dropped the video for Blue Electric Light’s lead single, “TK421.” (Why did that song get tapped to go first? Kravitz played the unreleased LP for a couple friends—you know them as Bono and the Edge of U2—and they were insistent. “They even texted me days later, saying, ‘You really need to come out with that one first.’ ”)

It’s a glamorous sprint of events, sure, but also kind of a grind—and at this point in Kravitz’s life, totally optional, at least financially. When artists could still make money off selling records, he sold a hell of a lot of them. He lives in an eight-bedroom townhouse in Paris. That farm in Brazil? It’s one thousand acres. There’s the Bahamas place, too, of course.

I suggest as much and Kravitz shrugs, but Jay-Z gets what I’m saying: “There was a point early on that I was like, ‘How is this guy so sick? Like, what’s going on?’ Just his lifestyle. He’s like a Renaissance man—living between Paris and New York. And then I remember that he writes and produces. There’s no one else in the process. I remember thinking how extraordinarily talented he is, and then I remember thinking, Wow, those publishing checks. . . .”

He could probably take a break if he wanted. “But what is that?” Kravitz says in response. “You know what I mean? What drives me is the creative.” It’s not just something to do; it’s the thing to do. His raison d’être.

The most grueling extension of his creativity is, without a doubt, touring. Thirty-four years in, Kravitz knows what it takes to prepare for years on the road. “Your life is that” once tickets go on sale, he says. “Your whole life is centered around being able to do those two and a half hours every night. So you don’t hang out. You don’t smoke. You don’t drink. You don’t talk a lot. You’ve got to get your sleep.”

You have to want to do it, in other words. You have to need to do it. “It doesn’t just happen,” Kravitz cautions. But he won’t stop anytime soon. He’s built his entire existence around being able to do it. And there’s a Bahamian phrase for that as well: If you love it, let it kill you.

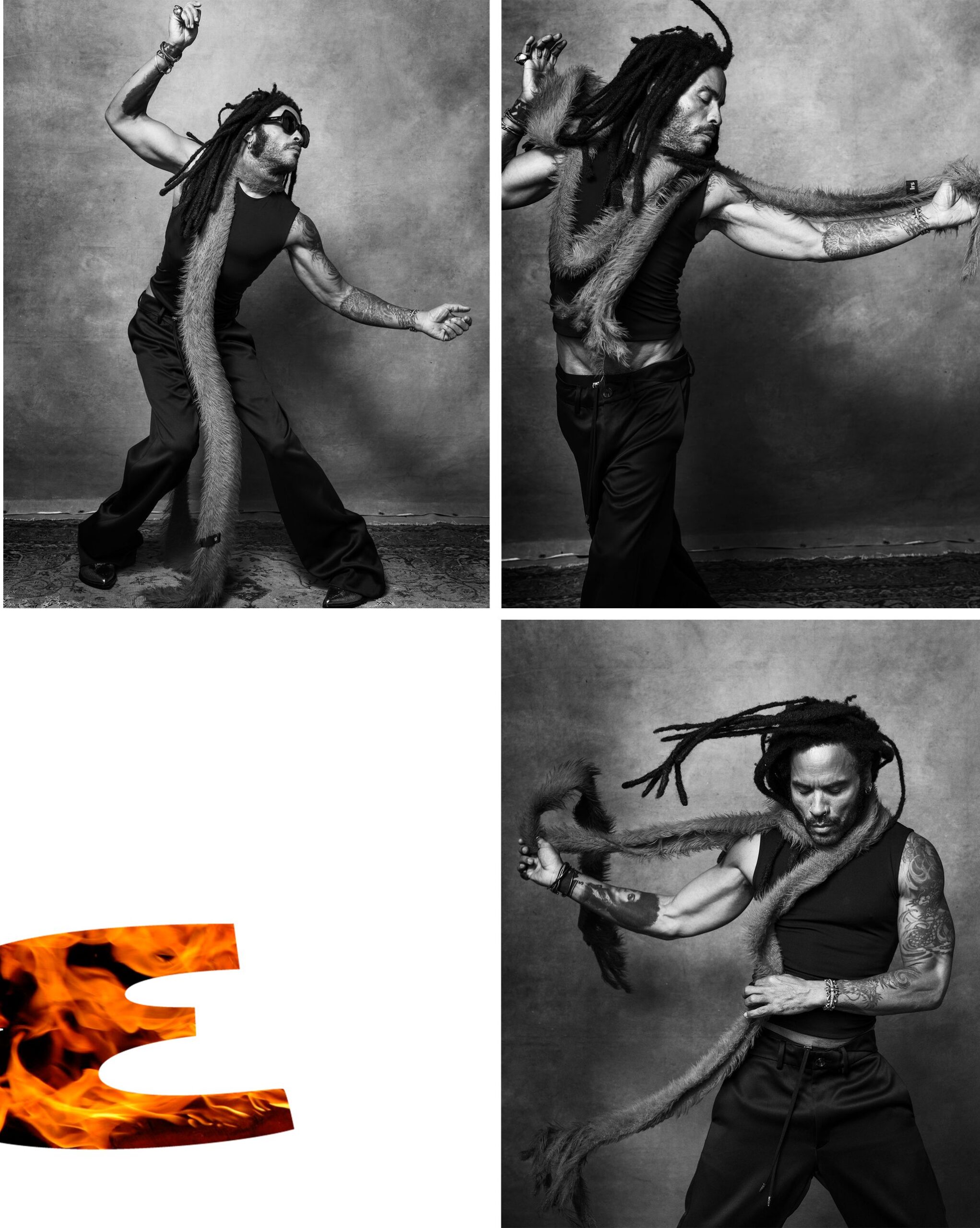

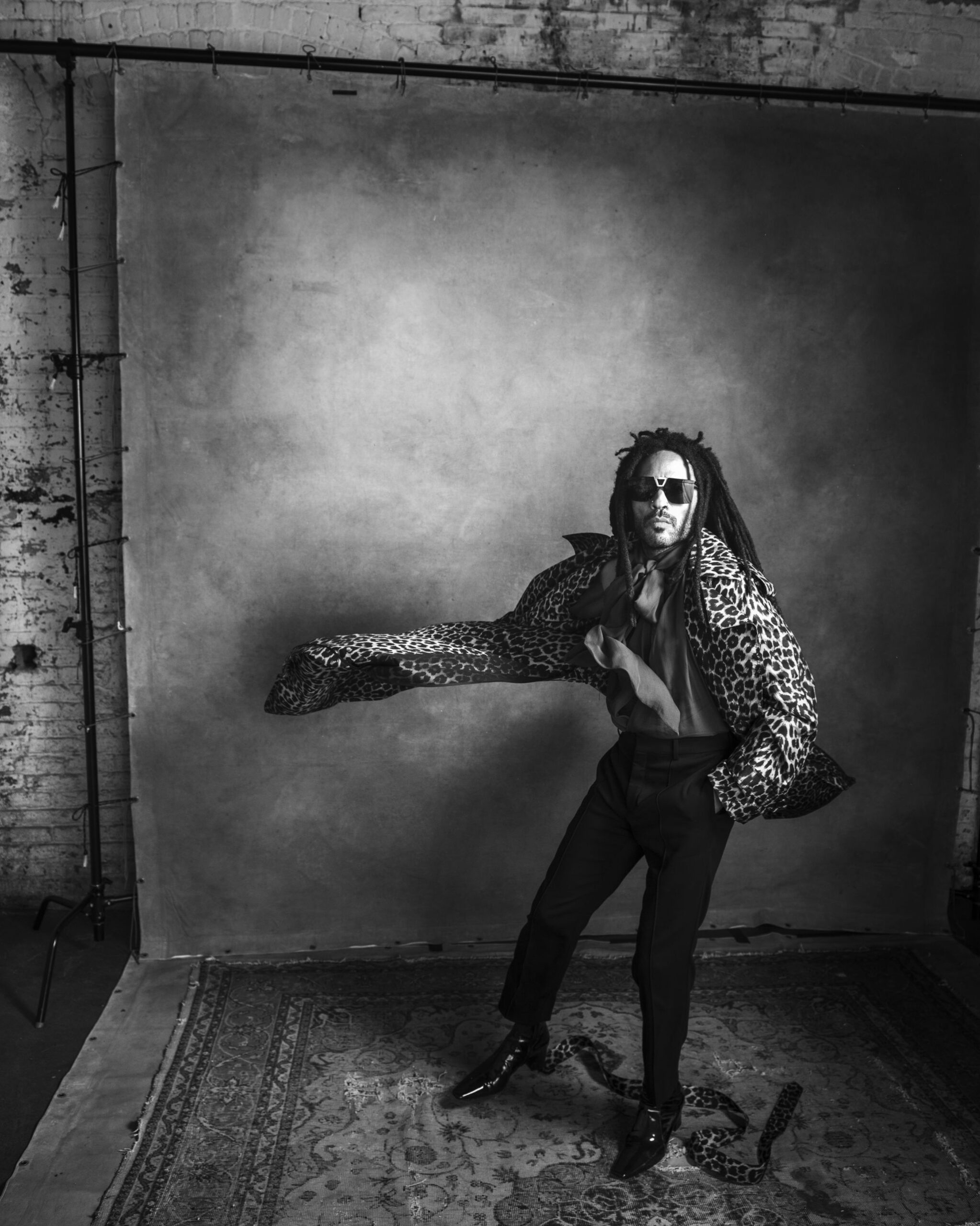

Opening image credits: Top, jeans, and boots by Rock Owens; gloves by Urstadt.Swan; sunglasses, Kravitz’s own.

Story by Madison Vain

Photographs by Norman Jean Roy

Styling by Matthew Henson

Grooming by Gianluca Mandelli

Set design by Michael Sturgeon

Production by Boom Productions

Design Director: Rockwell Harwood

Contributing Visuals Director: James Morris

Executive Producer, Video: Dorenna Newton

Executive Director, Entertainment: Randi Peck

Madison Vain is the Digital Director at Esquire; a writer and editor living in New York, she previously worked at Entertainment Weekly and Sports Illustrated.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.