Hip hop’s humble beginnings hardly hinted that it would grow to see a half-century of cultural influence, but the phenomenon is on display daily. Reaching far beyond music, the movement has developed its own aesthetic language that has permeated fashion, entertainment and the arts.

The current ubiquity of streetwear was preceded by eras of evolving hip-hop-inspired trends—some pulled from mainstream fashion, and others engineered from entirely new ideas. Denim weaved a common thread connecting past and present, according to Elizabeth Way, the Museum at FIT’s associate curator of costume: “Denim, especially jeans.”

By the ’70s, they’d become a staple of youth fashion in the U.S. So, when hip hop got its start, MCs, beat boxers, DJs and B-Boys were clad in blue, Way said. The New York City museum’s spring retrospective, “Fresh, Fly, and Fabulous: Fifty Years of Hip Hop Style,” was an exploration of the movement’s progression and its lasting impact on the way people dress.

Emerging in the South Bronx in 1973, hip hop originated “in a working-class area that was deeply impacted by discrimination, unemployment, and urban redlining,” the curator said. The museum traced the birth of hip hop to a “legendary back-to-school party” held at the apartment building of Cindy and Clive Campbell, also known as DJ Kool Herc, one August evening. From the beginning, “Hip hop kids were wearing the same jeans as young people around the country…but practitioners put their own spin on them,” Way said, from sewing permanent creases into the legs to adorning them with letter patches. Early favorites included Lee, Calvin Klein, and Jordache—“the same brands that were popular in mainstream youth fashion.”

A bona-fide hip-hop aesthetic “blew up” in the mid-’80s when widely influential stars and rap groups from LL Cool J to Slick Rick and Run-D.M.C. hit the scene, according to Rolling Stone’s fashion writer Kyle Rice. “Their music changed the way that people understood hip hop,” he said. “Because they went so global, people started paying a lot more attention to what these artists were doing, and that included the things they were wearing.” Denim was a constant component of those looks “because it was such a utilitarian product,” Rice said. “A lot of working-class families already had it as part of their wardrobes.”

“Denim has been the fabric of choice for teens and music culture—from rock and punk to disco and hip hop,” Elena Romero, FIT assistant chair of marketing and communications, said. Early acts like Funky Four Plus 1 were known for wearing head-to-toe denim, while Run D.M.C. gravitated to straight leg fits and West Coast groups like N.W.A. donned dark washes and workwear, she said. Over the next 10 years, denim became “synonymous with rappers,” including Biggie Smalls, Tupac, Snoop Dogg, DMX, Jay-Z, Wu Tang Clan and TLC.

Commercial era

The 1990s were a golden era for hip hop and the fashion it inspired, leaving a mark on the industry still visible today. The baggy silhouettes that came to define the decade represented “an innovative change in proportion,” significantly impacting both men’s and women’s styling, Way said.

Founded in 1985, Tommy Hilfiger blended yacht club-prep school chic with Norman Rockwell Americana—an ethos that, on its face, would seem unlikely to resonate with the movement taking shape in urban enclaves. But as hip-hop acts began embracing the brand’s clothing, the label perceived an opportunity to reach a new audience.

Rapper Grand Puba gave the brand one of its first rap shoutouts, referencing his “Tommy Hilfiger top gear” in 1992’s “What’s the 411?” with Mary J. Blige. The flame was lit. In 1994, Snoop Dogg performed on “Saturday Night Live” in an oversize red, white and blue long-sleeve polo shirt—a watershed moment that led to massive sellouts within a day of the show’s airing, the brand told Rivet.

Two years later, the label launched Tommy Jeans, a line of denim and casual apparel created to appeal to a younger set. Wu-Tang Clan’s Raekwon walked in the collection’s debut fashion show as Q Tip, Mary J Blige and TLC watched on. Tommy Jeans played to the prevailing hip hop denim trend—a mid-wash, roomy fit—adding identifying details that would become iconic, from carpenter loops to red, white and blue motifs on legs and waistbands, contrasting pockets and bold logos. Dungarees, cargo jeans and shorts were soon indispensable wardrobe staples.

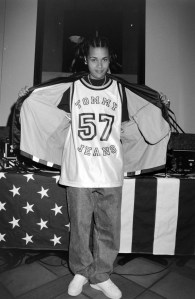

Actress Kadida Jones in Tommy Jeans in 1997.

Fairchild

It was one of the decade’s young female artists that shot Tommy Hilfiger into the stratosphere. Pop and R&B sensation Aaliyah was chosen as the face of the Tommy Jeans ad campaign in 1996, at the age of 17. Carefree and confident, she played to the camera in a midriff-bearing bandeau top and oversize jeans, sagged to reveal the waistband of her Tommy Hilfiger boxer shorts. The wide-leg, color-blocked, red, white and blue denim with bold graphic lettering became known as the “Aaliyah Jean” after the commercial aired. “I got Tommy Jeans—what else?” she quipped.

“We’re talking about a brand that for so long was catering to a white demographic. To now have this black woman as the face of his product—it was revolutionary,” Rice said of Hilfiger. “Brands weren’t going out of their way to feature black talent because for them, it was a risk factor.” Tommy Hilfiger’s embrace of hip-hop tastemakers “shifted the way people started looking at the silhouette of denim—how you pair it, how you wear it and what’s interesting about it.”

The designer maintains that music and pop culture have always been his core influences. With the rise of hip hop, rappers became the new rock stars, and he wanted them in his clothes. “Since its emergence, hip-hop made an unmistakable mark on fashion,” Tommy Hilfiger told Rivet. “It drove trends in the ‘90s, as this street style look spread from the U.S.A. to the world. To this day, fashion and hip hop are deeply connected,” he added. “Streetwear evolved from being a subculture into one of the most powerful drivers of pop culture today.”

Music to moguls

Other major mainstream brands, like Ralph Lauren, were propelled to greater heights as they were co-opted by hip-hop talents and their fans. But the mid-‘90s also ushered in the era of hip-hop moguls—“artists entering the fashion business with their own fashion brands,” Romero said. Chuck D’s Rapp Style International, Russell Simmons’ Phat Farm, Naughty by Nature’s Naughty Gear, Wu-Tang Clan’s Wu Wear, Jay-Z and Damon Dash’s Rocawear, Pharell Wiliams’ Billionaire Boys Club and Ice Cream, Eve’s Fetish and T.I.’s Akoo Clothing were among the ventures launched during this time.

“One brand that was extremely influential was Sean John,” founded by Sean “P. Diddy” Combs, “because it created a space in the mainstream fashion industry for respected artists’ or ‘celebrity’ brands,” Way added. Combs became the first Black designer to win a Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) award in 2004.

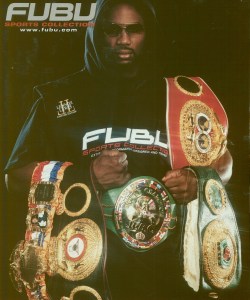

Founded by Daymond John, Carlton Brown, J. Alexander Martin and Keith Perrin in 1992 in Queens, N.Y., FUBU grew into the stuff of hip-hop legend, grossing hundreds of millions of dollars annually at its peak. Built on distinctive styling and close ties to the music industry, its “focus and origination” stemmed from the desire to create “clothing that was really meant for us—‘For Us, By Us,’” Martin told Rivet.

“When we first started our company, we were just kids buying clothing that was available to us from different brands, but none of the brands really fit the way we wanted,” Brown added. “We’d buy the clothes three times larger so they would be baggier.” The founders set out to develop a line that they, and their contemporaries, would want to wear straight off the rack. “This was a time when there was no ‘urban fashion,’” Brown said.

FUBU ad

courtesy

“It was easy for us to transcribe our thoughts into designs because we were the customer,” Martin explained. “We know what we like to wear. We know why we want to wear it. We know our own sensibilities as far as length, width, shanks, buttons and pockets.”

FUBU became known for its core staples, from brightly colored, heavyweight “FB” logo hoodies to athletic-inspired jerseys, baseball caps and oversized T-shirts. And of course, the jeans—billowing wide-legs in “hard,” rigid, dark denim. “From CAD all the way to production, from the stitching to the details, every little thing mattered, and we had a reason for it,” Brown said. A small stash-away pocket on the inner waistband offered discreet storage—a proprietary feature that the partners pushed as indispensable, even when suppliers balked. “The manufacturer asked, ‘Do you have to have this pocket in the jeans?’ and we said absolutely because we know how important things like that are.”

FUBU’s physical proximity to the borough’s up-and-coming hip- hop artists proved a major boon to the brand, according to Perrin. “We grew up in an area where Run D.M.C., Russell Simmons and LL Cool J lived, and on the Queens side, they were some of our first artists to make it big.” He credits Hype Williams with helping to spread the word about FUBU. Already a prolific director of music videos in the ’90s, Williams worked with “every hot artist out there,” and tipped off the FUBU team to opportunities to get their clothes on the small screen.

“He would call us and tell us, ‘Hey, I’m shooting this person,’ and we’d be on set for 10, 12, or 14 hours a day just to get one shirt or one hat on them,” Perrin said. “Sometimes we got it, sometimes we didn’t, but we got to know a lot of artists in the early days when they were just coming out.”

LL Cool J gave FUBU one of its winningest shoutouts—and in another brand’s commercial, no less. Hired to perform a freestyle in a 30-second ad for Gap menswear in 1999, the rapper slipped in the line, “For Us, By Us, on the low,” while wearing a FUBU cap. The spot blew up, and it took Gap weeks to recognize the unintentional cross-promotion.

FUBU in Macy’s Herald Square

Courtesy

Perrin said grassroots, on-the-ground marketing boosted recognition in the early ’90s before FUBU made it onto the backs of the greats. Touring expos and trade shows, the brand racked up orders, and soon demand outpaced supply. John placed an ad in the New York Times seeking financing. In 1996, Samsung’s fashion and textile division said it would help with distribution and expansion if the brand could generate $5 million in business over three years. FUBU blew the sales target out of the water within weeks.

“[Samsung] said, ‘They did what they said we needed them to do—now let’s open up the floodgates,’” Perrin said. “That allowed us to jump out in the market in a huge way.” By 1998, yearly global sales amounted to more than $350 million.

Remix Style

Three decades since its founding, the brand is undergoing a resurgence, fueled by a wave of ’90s and early 2000s nostalgia. The music of the times has come roaring back with a vengeance, from the 2022 Super Bowl LVI halftime show, which featured Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre, Eminem, Mary J. Blige, 50 Cent and Kendrick Lamar, to the Grammys in February. Music’s Biggest Night celebrated hip-hop’s golden anniversary with a whirlwind of performances that included Run-D.M.C., Salt-N-Pepa, LL Cool J, Big Boi, Busta Rhymes, Grandmaster Flash, Ice-T, Nelly, Missy Elliott, DJ Jazzy Jeff and De La Soul.

Salt-N-Pepa in 1988

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

“I’ve noticed that within the last year there has been a huge uptick in interest, especially from younger kids, 18 to 25,” Brown said. 2022 saw FUBU resurrect some of its famed silhouettes through a capsule with Forever 21. In February, the fast-fashion retailer teamed with hip hop supergroup Mount Westmore—comprised of California-based rappers Snoop Dog, Ice Cube, E-40 and Too Short—on a line of ’90s-inspired merch.

Brown is relishing the return to classic hip-hop styling. “One thing I like that I’m starting to see is Offset and other rappers going for baggier jeans,” Brown said. “We’re actually talking about putting out a couple of older style jeans—more collectible, vintage type jeans,” Perrin added, along with two-piece denim suits.

Martin is eager to see a younger generation breathe new life into the brand, and sees serendipity in todays’ retro renaissance. “I just feel as a company, we’re blessed because we came at the right time,” he said. “We’ve touched a few different generations with one brand, and not too many people can say that.”

Founded 10 years after FUBU in Vernon, Calif., denim label True Religion is also finding itself the beneficiary of renewed interest in Y2K fashion. Breaking onto the scene in 2002 with ultra-low-rise flares, prominent stitching and a happy Buddha logo, the brand made waves with the era’s sartorial sovereigns, from It Girls and heiresses to rappers and R&B artists.

“We had a bold aesthetic, and that was no doubt the reason we were adopted by the hip-hop community,” said Zihaad Wells, True Religion global brand creative director. “It was never a conscious choice by us—we were just doing our thing, and luckily that heads-down, unapologetic attitude that we had resonated with the tastemakers in the hip-hop scene.”

The brand helped usher in an age of luxury denim that spawned labels like 7 For All Mankind, Citizens of Humanity and Rock & Republic. A far cry from the rugged and practical workwear of decades past, jeans in the 2000s retailed for upward of $200, and were encrusted with crystals and sequins and embellished with patches and distinctive stitching. “Our stitch denim with the flaps were what really put us on the map within the music community,” Wells said. “The guys were rocking our Ricky with the stitch”—a loose-fitting straight leg—”while women were rocking the lowriders.” Elongated back pockets featured True Religion’s unmistakable calling card—a stitched horseshoe motif.

Throughout the decade, True Religion jeans became “a mainstay style choice” and a status symbol for artists, culminating in the ultimate callout from 2 Chainz in the form of a mixtape dubbed T.R.U. REALigion. “We had seen elements of exposure within the community, but that was the moment it became evident,” Wells said of the 2011 release. “It wasn’t a surprise as much as it was an, ‘Oh right, of course.’”

After that it all clicked—”Legends like Chief Keef, Skepta, and Fergie ran it up and made True Religion a signature within the world of hip hop to this day,” he added. A decade after the mixtape drop, True Religion teamed with 2 Chainz on a capsule collection of apparel and denim. “It’s become part of the DNA—we’re constantly turning to our community of hip-hop artists to see how we can evolve our designs,” Wells said. That includes “collaborating with the artists that put us on the map many years ago.”

True Religion x Chief Keef

Courtesy

The brand feted its 20th year in business—and the 10-year anniversary of Chief Keef’s song, “True Religion Fein”—with a denim and streetwear drop last year. In November, it released a women’s collection with hip hop and R&B singer Dreezy, which included a denim trucker jacket, jeans, cargo midi skirt, and a denim wrap top and bustier. “This year we’re cooking up something with a bunch of new hip-hop artists,” Wells added.

The brand is eager to deepen these associations as it works to cultivate a connection with a new generation. “Young people have always looked to artists to see what they should be wearing, and hip-hop artists have looked to the younger generation to see what’s cool,” the designer said.

“Hip hop has a huge influence on mainstream fashion because of its synchronicity with youth culture,” he added. “It’s all intertwined.”

This article appears in Rivet magazine. Click here to download the issue.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.