“I’ve been called [the “N” word] in the workplace, by the company’s CFO. He waited after a meeting for everyone to leave and it was just us two. Had I brought something like that up [to management or HR], it would have been a ‘he said/he said’ moment. I don’t think I would have won that fight.”

“A board member slapped and pushed a black junior colleague who was in her way. The same board member was rude to and harassed the black man working on reception – because without her staff pass, which she had forgotten, he wouldn’t open the gate.”

These are just two of the shocking experiences readers have shared with Drapers as part of our investigation into racism in fashion retail, to see if attitudes, behaviour and representation have changed following pledges and the introduction of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) strategies and initiatives in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020.

We asked our readers to share their experiences in a confidential survey between 9 May and 26 June to investigate incidences of racism in fashion. Of the 75 respondents, more than hald (56%) have endured or witnessed racism and/or racist discrimination in the workplace. Three respondents even report the use of the highly offensive “N word” in the workplace. Fashion retailers tell Drapers they have suffered or witnessed insults and comments about skin colour and accents from colleagues – and have even witnessed physical violence.

“It’s almost like a suspicion. Like I’m not supposed to be there,” one respondent tells Drapers, of how their colleagues make them feel. “Or that I am, but only because I was lucky enough to be employed (…) There’s this feeling of suspicion, like, ‘Can we trust him?’”

Advertisement

Another respondent – of Asian heritage at board level at a fashion retailer – says they have “been the focus of toxic bullying in the workplace.”

The founder of one menswear brand describes the shocking treatment of his co-founder (who is black) by others in the industry: “He has been refused entry after showing his registration [at trade shows]. He has been told he isn’t the designer after giving them his card, and been asked where the streetwear is – we are a tailoring/heritage business. [People] regularly ask to talk to his ‘boss’ – we’re equal partners. We have done co-labs where he has been asked to bring in the coffee. On one drunken evening I was asked how I can work with ‘one of them’ by someone who is a considered a legend in our market.”

One respondent at management level at a brand in London says they have experienced “undermining” treatment: “[I have been] told that people of my origin ‘must have very proud parents because I must be the first in my family to get an education’ and [I have been] overlooked for promotions constantly by white bosses.”

Many respondents report this type of less “overt” discrimination, such as micro-aggressions, which are comments or actions that subtly and often unconsciously or unintentionally express a prejudiced attitude towards a member of a marginalised group, such as an ethnic minority (also known as the global majority), and unconscious bias – whereby a person acts on subconscious, deeply ingrained biases, stereotypes and attitudes. Many also observe a lower rate of promotion for people from ethnic minority groups, and reported double standards being applied to people from different backgrounds. A sobering 53.5% say they did not believe there are equal opportunities for people of all ethnic backgrounds at their organisations.

For example, one respondent reports that people from ethnic minority backgrounds are left out of meetings, that managers describe places associated with racial diversity as “the ghetto” and prevent buyers from ranging certain products [associated with ethnic minorities] because they will not sell well.

Advertisement

Another says they have experienced racist discrimination that is hard to quantify – “It felt like [discrimination] but it was based on favourites and back talking about different ethnic people” – while one describes unconscious bias as being “rife”.

Worryingly, the incidents are often top-down, and those in senior positions are the perpetrators of this discriminatory behaviour.

One respondent says: “[There is] more micro-aggression-related racism in head office. The senior leaders are majority white, male, upper class – there are comments [made] that are clearly aimed at non-white colleagues.” Another recalls “toxic descriptions of people by leaders based around race”.

Respondents tell Drapers that many fashion retail HR reporting systems are often either not fit for purpose or non-existent. Of those who have experienced or witnessed racist discrimination, more than a quarter (26%) did not report the incident.

One says: “When [the racist discrimination], happened there was no process to follow.”

When asked why they did not report an incident, another respondent says: “You’d get the sack or get overlooked for promotion – seen as a troublemaker for speaking up. It’s hard enough to get a job.”

“Fear of being pushed out of the role – ie strategically made redundant,” says another.

While one respondent accused HR: “They don’t really care about indirect racism or entry-level workers.”

One respondent points to a lack of diversity as being a factor in speaking up about racism: “Being one of the few black people in the office meant that I didn’t know who to trust.”

Many tell Drapers even when they did report, outcomes were less than satisfactory. One even describes being gaslit – in which an individual’s perception of reality is repeatedly undermined or questioned by another person – by their HR representative: “[My reporting of the incident] was quickly quashed and I was made to feel like I was completely mistaken in thinking that would happen.”

Another says they were told “to grow up”, while one adds: “Nothing was done because it was not considered a race issue but a clash of personalities.”

“HR aren’t there for the employees,” claims one management-level fashion retail professional, starkly. “They are there to protect the company. I’ve seen this first hand in huge organisations I’ve worked at.”

On a positive note, one respondent – at management level in a premium high street retailer’s head office – says that although in the past they have not reported discriminatory comments, they now would do so: “There are fantastic policies and processes in place, and there’s been a huge drive to make EDI [DEI] at the forefront of our culture.”

Lack of progress

Progression – or lack thereof – comes up time and again, as a form of discrimination but also as stifling diversity at senior levels of business, and therefore perpetuating cultures in which discrimination festers. More than half (53.5%) of respondents who answered the question say they do not believe there are equal opportunities for people of all ethnic backgrounds at their organisations. When asked if they think this had improved since 2020, 50% say they do not.

“[High street retailer] has recruited a lot of non-execs to tick minorities boxes,” points out one respondent. “But recruitment from within, to tackle representation, has not happened. Unless it’s from the bottom up, it isn’t going to affect tomorrow’s leadership pipeline. Seriously, I think the board view black people as scary aliens.

Another echoed this concern around progression and recruitment at all levels: “They say they do [have initiatives in place to increase representation] but it’s all aimed at junior and younger employees – very little for management level or aspiring senior managers.”

One respondent describes the double standards at play when it comes to career trajectories, as well as the intersection of gender and ethnicity: “White males get by without having to take on extra projects or multitask to prove worth so they never get judged on these projects and are judged only on ‘potential’ imagined future performance – whereas women and people of colour are judged on actual retrospective performance, and have to prove themselves over and over and over again by taking on extra projects, moving sideways, and ticking every skillset before promotion. That takes years, so they fall behind on the ladder and are seen as ‘less’.”

Another agrees: “I think there are unconscious cultural stereotypes [whereby] women and people of colour are seen as ‘disruptive’ instead of assertive or held to a higher standard than white males in order to progress. I have seen and heard this in promotion reviews, where white males are described as ‘good blokes’ and therefore worthy of promotion on the nod, but women – and people of colour – have every project or initiative ruthlessly scrutinised and only 100% success will do.”

Many note the ethnic disparity in different sorts of roles in businesses. For example, one hearing their creative director say they would only consider graduates of London College of Fashion or Central Saint Martins for employment in the design team – “these students aren’t always racially or culturally diverse”, the respondent points out – and another saying: “In buying and merchandising, of about 400 people, only 25-30 were from ethnic minorities. Of that, there were only about five managers.”

This is all despite a swathe of DEI strategies and positions being created in fashion retail businesses in recent years. Companies such as Asos, Burberry, Depop and Pentland Brands have all launched initiatives – such as employee-led steering groups, working with specialist third-party organisations to engage with diverse early talent and rolling out new internal training – aimed at increasing representation and inclusion, and improving company culture. Many have appointed dedicated DEI leads to head up strategy.

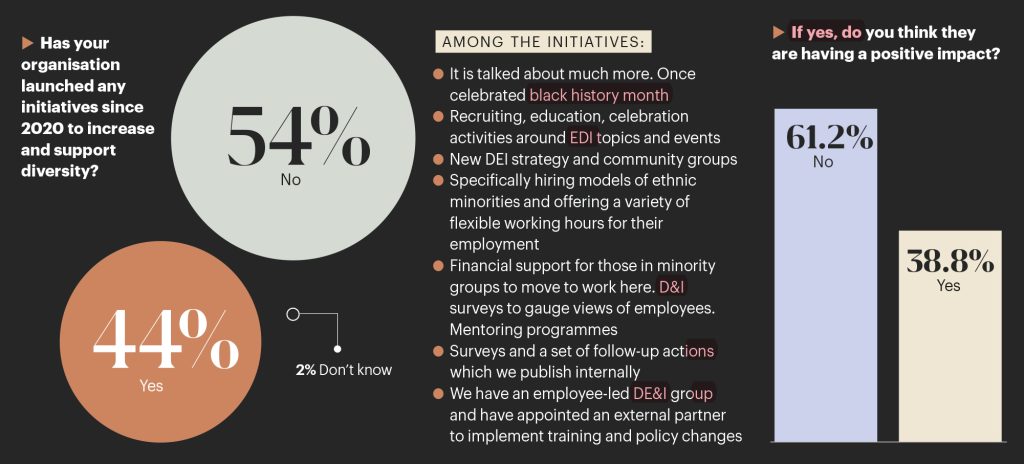

Survey respondents do acknowledge similar efforts in their businesses – with mixed results.

“We have an employee-led DE&I group and just appointed an external partner to implement with training and policy changes,” says one respondent. They tell Drapers this is changing how they view reporting processes: “Up until the appointment of our DE&I partner a couple of months ago, the answer would have been no [to reporting racist discrimination to HR]. However, I do now feel like I can go to HR going forward.”

Another also notes a culture shift in their organisation: “I think [discrimination] has decreased [since 2020], or people are more aware of it – and apologies [and] acknowledgement is a good start.”

But one respondent is more cynical about efforts: “When ‘unconscious bias’ became the next big thing, everyone was ordered to watch a certain video training. This was poorly selected. The team members who came from ethnic minorities were quite obviously offended.”

One respondent says their business has only approached DEI on a surface level: “In 2020, there was a massive focus for bringing in black-owned business and products [for sale] that represent ethnicity, and [the business] said we need to do this for commercial reasons, to bring in new customers. That should not be the reason [to do this], just to jump on the latest racial band wagon. It should be done because it is the right thing to do. Sadly, three years later, it [the business’s approach] has gone back to pre-BLM movement.”

This is reflected across the survey: 93% of respondents saying that – despite ongoing internal inequality at businesses – external, consumer facing fashion campaigns have become more diverse since 2020.

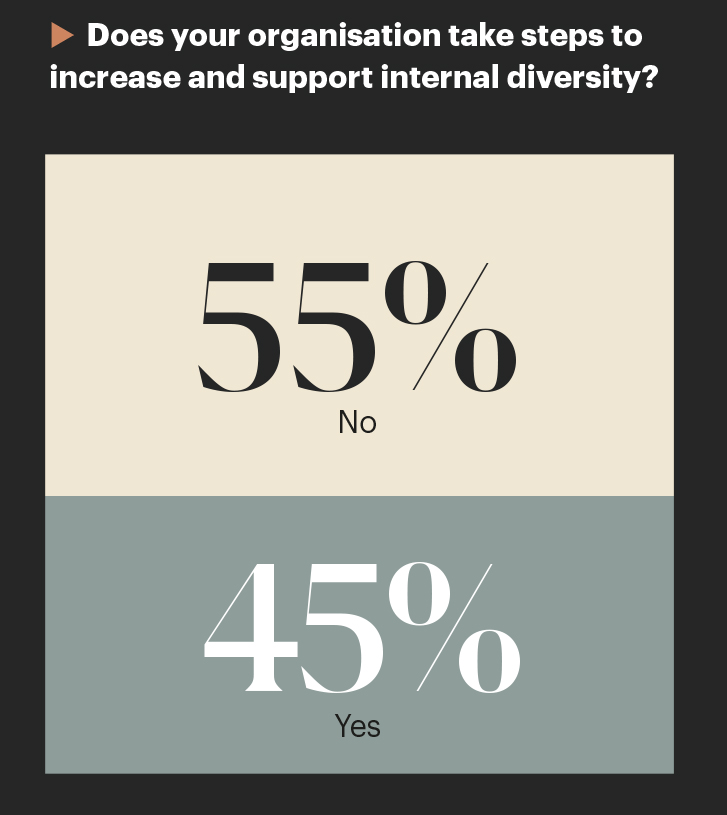

And while many noted there has been an increase in activity such as DEI training, “huge initiatives in place around training, education, recruiting, and celebrating all factors of [DEI]”, and “internships, apprenticeships and mentorship programmes that are arranged by charities and companies specifically founded to increase opportunities and visibility of diverse applicants,” multiple respondents described such activity as merely paying “lip service” rather than taking responsible action, and many seemed doubtful of the impact, especially at senior levels of the business.

“[The business] does [take steps to increase and support internal diversity] on paper, it but feels like lip service when not represented at senior levels,” reported one respondent.

Another adds: “There are several ethnic minority programmes geared to enhance careers, but they don’t seem that successful.”

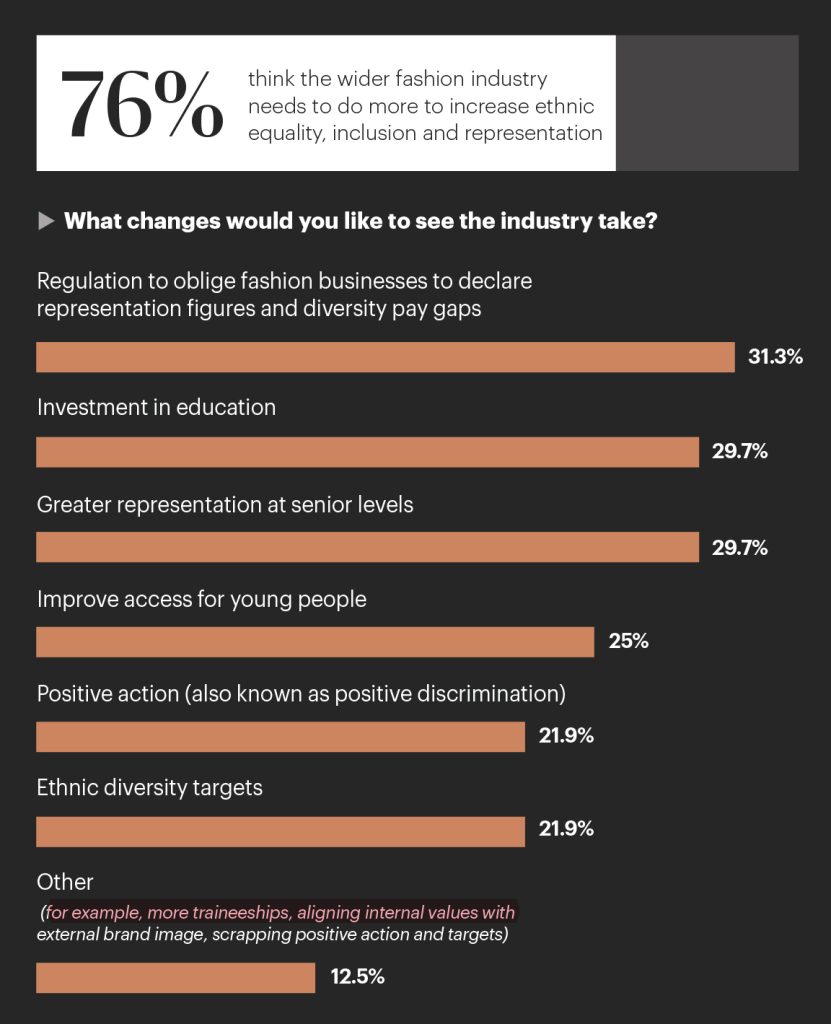

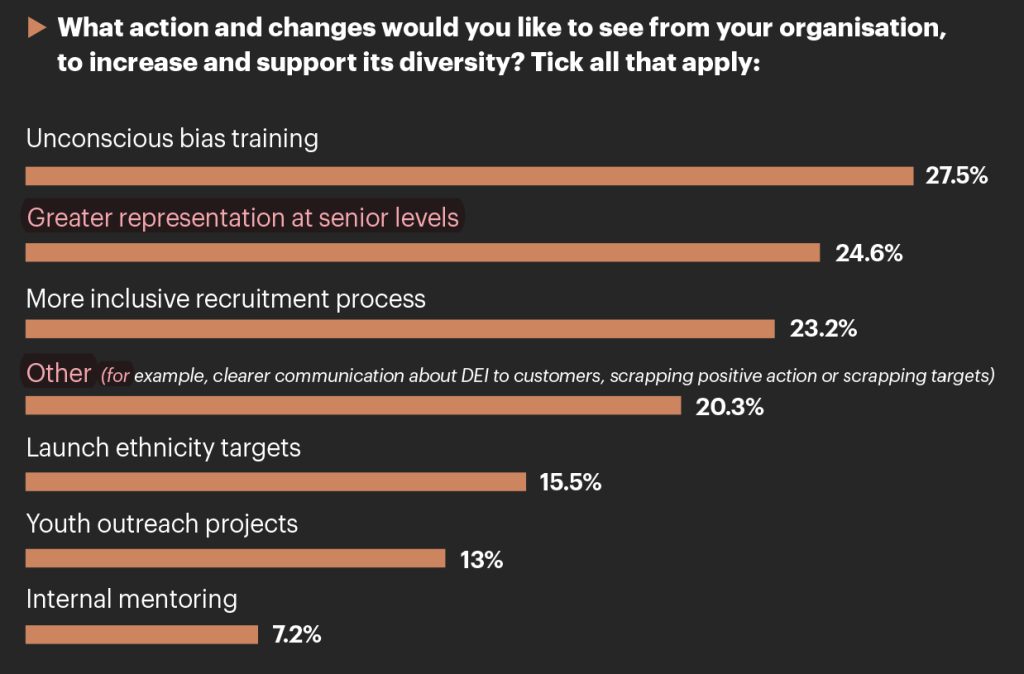

Greater diversity at the top of business is important to fashion retail professionals: 78% of respondents to Drapers’ survey say companies should be required to publish the diversity of their boards. When asked “What action and changes would you like to see from your organisation, to increase and support its diversity?” the most popular action response is unconscious bias training, followed by a more inclusive recruitment process.

One respondent tells Drapers: “The challenge [to creating greater equity and inclusion] is when you have white leaders in the most senior of roles. Naturally that representation unconsciously presents itself – they pay it forward unconsciously for other colleagues who look the same.”

The best boards bring a variety of voices, backgrounds, and experiences around the table, hence in 2017, the Parker Review set the FTSE 100 the target of appointing at least one non-white director by 2021, and by 2024 for the FTSE 250. In an update published in March this year, it found that 96% of FTSE 100 companies met the target – and of these 96 companies, 49 have exceeded the target by having more than one ethnic minority director on their board – while 149 out of 224 FTSE 250 companies who submitted data (67%) currently meet the December 2024 target.

However, almost a third of British retail boards have only white members, the British British Retail Consortium (BRC) and MBS Group found in a diversity survey published in June. It shows that progress has been incremental since its first report in 2021, despite commitment from 93% of retailers to improve diversity and inclusion across their businesses.

Ethnic diversity on boards has improved by five percentage points since 2021, and 10% of board positions across the retail sector are now held by ethnic minorities. However, 30% remain all white, which is well above the 4% of companies on the FTSE 100 that have all-white board membership, and not reflective of the wider population – the 2021 census shows that 81.7% of the population of England and Wales identifies as white. Scotland and Northern Ireland are less diverse – Audit Scotland’s Annual Diversity Report 2021/22 shows that 95.4% of the Scottish population identifies as white, and the 2021 census shows that 96.6% of Northern Ireland identifies as white – but still by no means 100% white.

However, Elliot Goldstein, managing partner at The MBS Group, tells Drapers there is cause for cautious optimism: “[There is] more energy, more momentum, more noise than ever before [about DEI].” But he agrees more must be done: “I would encourage businesses to consider the representation at the board when making appointments,” as, at executive level, this seems to be “much more challenging” – “there is simply not a great [diverse talent] pipeline yet.”

Retail as a whole needs to think about the pipeline over the layers of leadership, and to invest in future leaders, Goldstein says. “There has already been huge progress since benchmarking, so [retail is] already starting to see fruits of that labour but it’s too slow, so leaders need to keep up [momentum]. There’s a moral imperative and a commercial imperative. [If you are not representative], there’s a whole aspect of the community that you’re missing out on.”

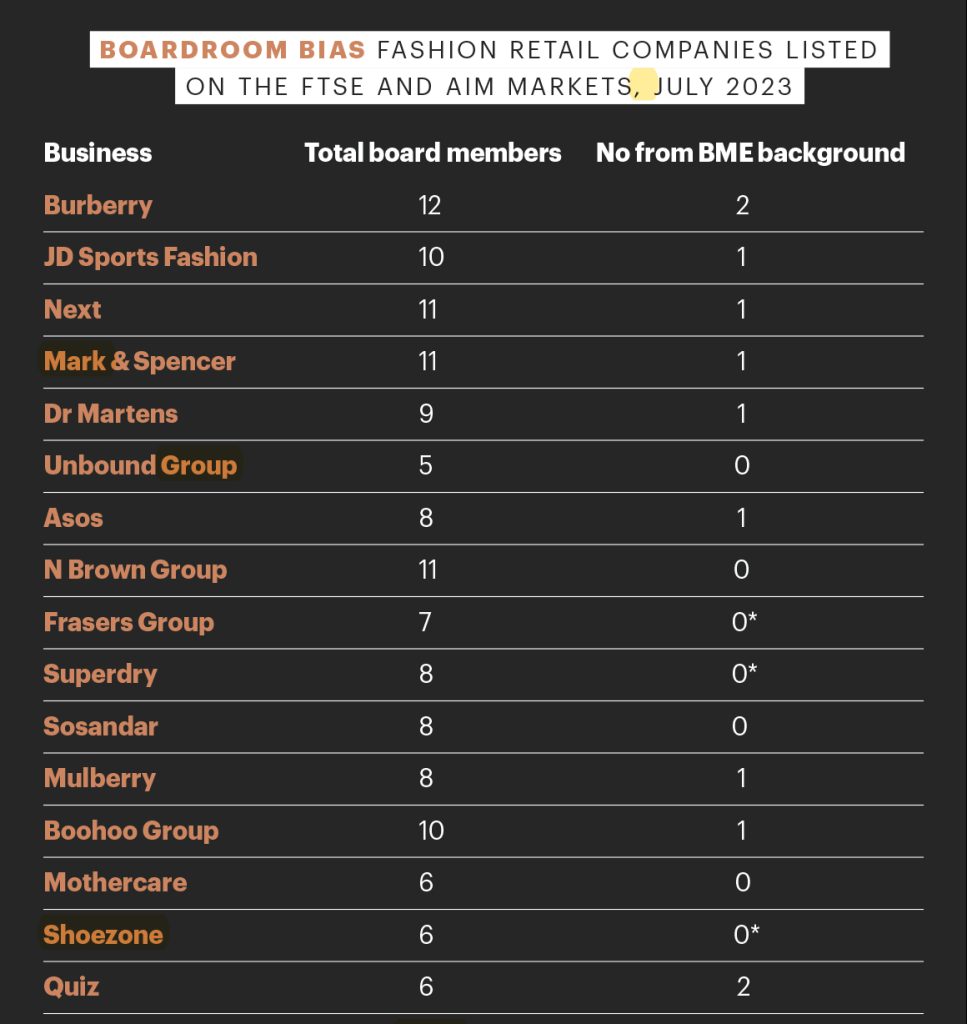

* declined to confirm Drapers’ analysis

CEO of the British Retail Consortium Helen Dickinson tells Drapers: “The challenge now is how to really shift the gear from activities to assessing which are working. What we’ve seen is a real change in focus – the breadth, the activity – in terms of ethnicity but also widely. It’s time to move from doing loads of stuff, to narrowing it down and doubling down on the things that are working. And to assess and track the impact of them, rather than having a wide set of [initiatives] that look like they’re ticking a lot of boxes.”

When it comes to fashion retail businesses specifically, Drapers’ 2023 investigation shows that – of publicly listed fashion companies – seven of 16 have no board members of ethnic minority identity (see table above), representing 44% – significantly higher than the 30% of businesses with all white boards across all retail, revealed by the BRC.

Some fashion businesses have increased diversity at board level since Drapers’ 2020 investigation. JD Sports, for example, had an all-white board but now one of its 10 members identifies as being from a minority ethnic background. But, as we found in 2020, while there is some diversity on fashion retailers’ boards, it is often just one member who identifies as coming from minority ethnic origins – there are no more than two members identifying as coming from minority ethnic origins on any of the publicly listed fashion business boards.

With more than three-quarters of respondents telling Drapers the wider fashion industry needs to do more to increase ethnic equality, inclusion and representation, and the shocking number who have experienced racist discrimination at a personal level, those working within fashion retail both need and want real change. While data shows this is happening, progress is slow – the industry must keep up the momentum sparked in 2020 in order build a better future for fashion and work harder to protect those working within it.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.