Trigger warning: This story contains discussions of assault.

As we chat beside a gorgeous hotel pool in Edgartown, Massachusetts, Hampton explains she got bored with the content. She even expresses, strikingly calm and soft-spoken, that she finds many male rappers of this era to be “snooze fests.” Nevertheless, the executive producer of Surviving R. Kelly and esteemed hip-hop journalist dove back into the genre with a new lens, focusing on women. In fact, her critical eye adds a unique and necessary perspective to Ladies First, which she executive produces alongside hip-hop legend MC Lyte and many others.

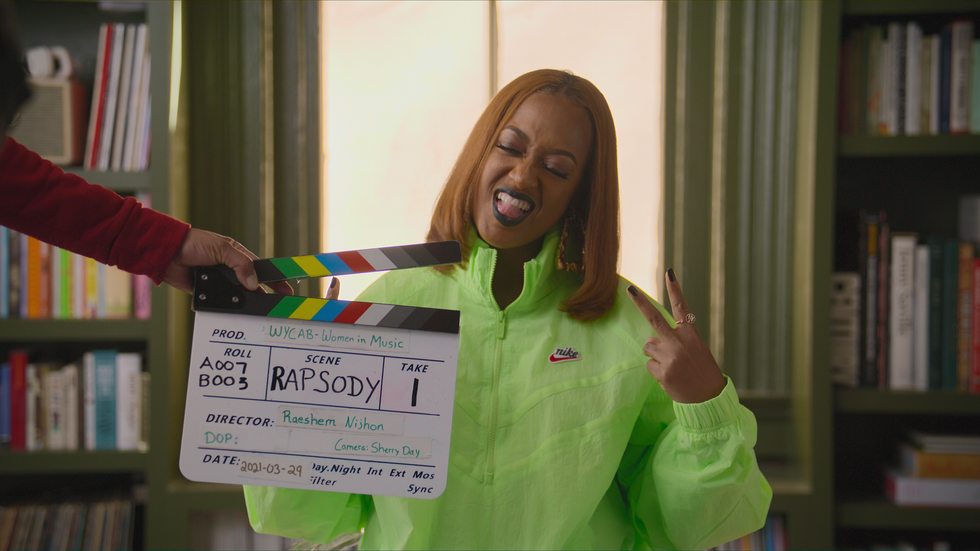

Out today, the four-part series is a dissection and celebration of female rap history, featuring legends like MC Sha-Rock and Queen Latifah in addition to this current generation of talent: think Chika, Tierra Whack, Latto, and Kash Doll. But the series is so much more than a historical record: it’s also a poignant snapshot of the good, the bad, and the ugly misogynoir that often lurks in the depths of hip-hop culture. Narrated by Rapsody, Ladies First nails it with its illuminating commentary provided by titans of culture storytelling: Kierna Mayo, executive director of One World; Brittney Cooper, professor and author; and Joan Morgan, author of the Black feminist classic When Chickenheads Come Home To Roost and more.

More From ELLE

Hampton was approached to executive produce by Carri Twigg, founding partner of Culture House, the Black and Brown women-owned production company and consultancy that produced Ladies First. (They’re behind Hulu’s The Hair Tales, and Disney’s Growing Up.) Though Hampton initially didn’t want to join the project, she eventually agreed because she recognizes that this is an important moment for women in hip-hop. “I don’t have to listen to a Cardi album or Megan [Thee Stallion] album to see that they’re the most interesting, and not just them. Young MA is [also] a revelation,” she notes.

Originally from Detroit, Hampton is known by many as a well-respected rap critic who began interning at The Source while attending NYU film school during the early ‘90s. Hampton worked at the rap magazine for 18 months and later went on to write for VIBE and The Village Voice. She also had close friendships with artists including The Notorious B.I.G. Yet even with her proximity to artists, she never backed down from writing skeptical and detailed profiles and features. Her writings carved out a lane for Black women writers and journalists who came after her who love hip-hop culture and aren’t afraid to critique it.

In 1991, after overhearing some staffers at The Source talking about Dr. Dre’s assault of rap TV show host Dee Barnes, she wrote an editorial about it. (He was charged with assault and battery in 1991 and pleaded no contest. In 2015, he issued a public apology “to the women I’ve hurt.”) She tells me that her budding relationship with Black feminist books was guiding her back then. “I was a little baby feminist reading bell hooks and Paula Marshall and Ntozake Shange, and just taking in all that great radical Black feminism from the ’70s and ’80s,” Hampton said.

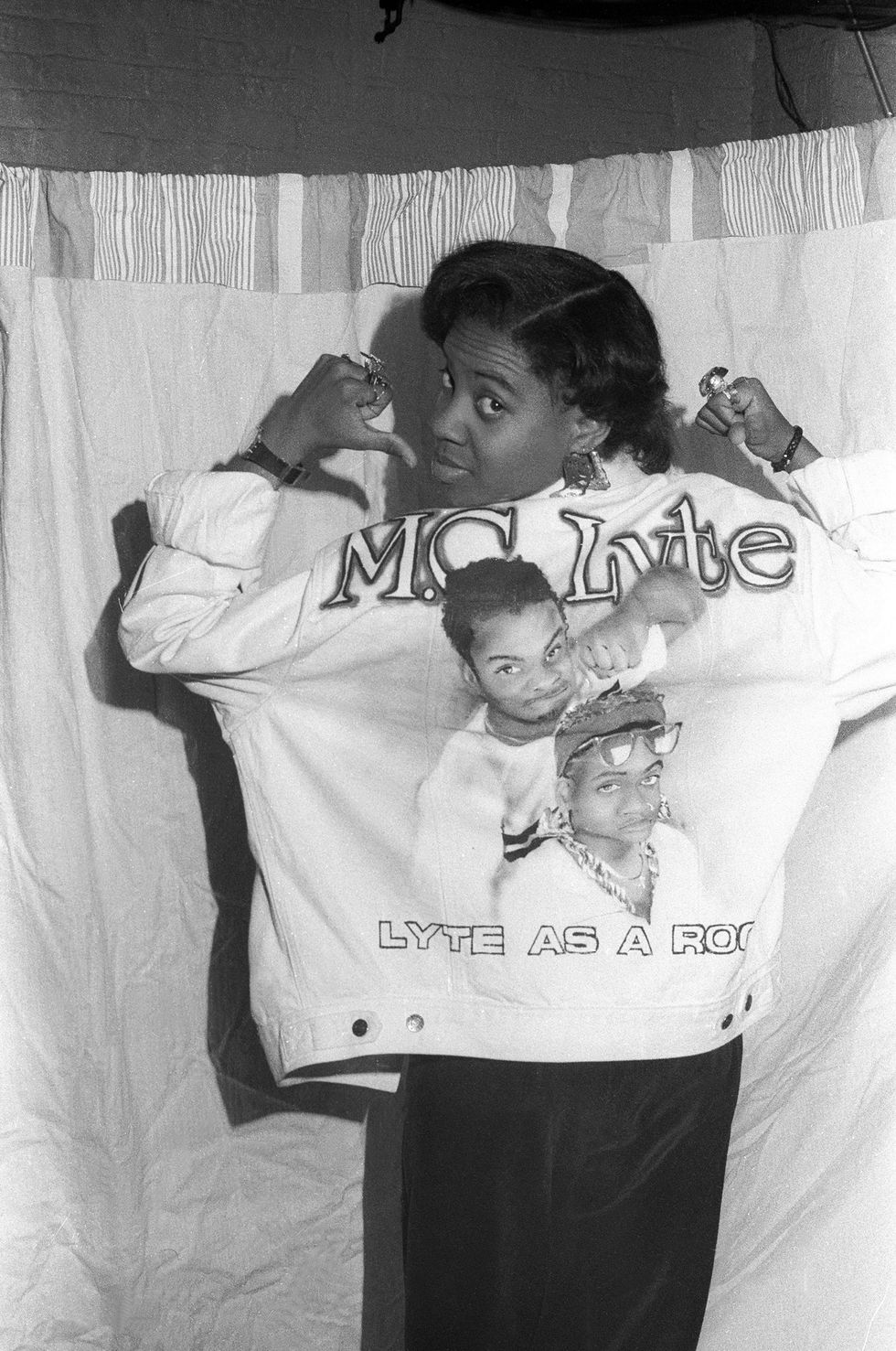

MC Lyte, a Brooklyn native born Lana Michele Moorer, is another one of hip-hop’s trailblazing legends. Her golden voice took years to perfect, she tells me over a call from Los Angeles. She always kept composition books where she wrote her rhymes, poems, and short stories. By age 15, she was in a rap group with a rhyming partner. “We would give a little bit of time, maybe once or twice a week [and] we’d get together after school to write,” she explains. “The name of the group was Pure Elegance, and my rap name was Sparkle, and hers was Dazzle.”

Within two years, MC Lyte began her professional music career in 1987 with her debut single “I Cram To Understand U (Sam).” By the following year she released her debut album Lyte As A Rock which would become the first full-length to be released by a solo female MC. It was largely successful too.

She believes Ladies First is important because it will create a moment for women who have felt unacknowledged for their contributions to hip-hop to finally be seen and heard. She feels it also provides space for the next generation of women rappers to shine including voices like Coi Leray. These optimistic messages are mostly seen in the first episode, titled “Shaping Hip Hop.”

Elsewhere, in episode three, “What Have They Lost,” Hampton’s critical perspective offers up questions grappling with the erasure and abuse women have faced in the music industry. This chapter features artists, producers and writers detailing unsavory, often jarring, personal stories. Dee Barnes cries as she reflects on Dream’s The Source editorial detailing the violence she endured by Dr. Dre. The series draws parallels to Megan Thee Stallion’s shooting by Tory Lanez, who was found guilty on all charges this year, and the attempts to deny her trauma. These are examples of Hampton’s journalistic rigor and her examining patriarchal power structures. They make the documentary so much more convincing.

Though the series already feels like a must-watch, Culture House founding partner Raeshem Nijhon says it took a lot of pitching to get Ladies First off the ground. “People didn’t understand the power of centering women,” she shares. “The process of pitching this show emboldened us,” she adds. Though the project was merely an idea five years ago, thankfully, Nijhon recalls, Jamila Farwell, director of documentary series at Netflix, immediately resonated with their pitch. All the work paid off.

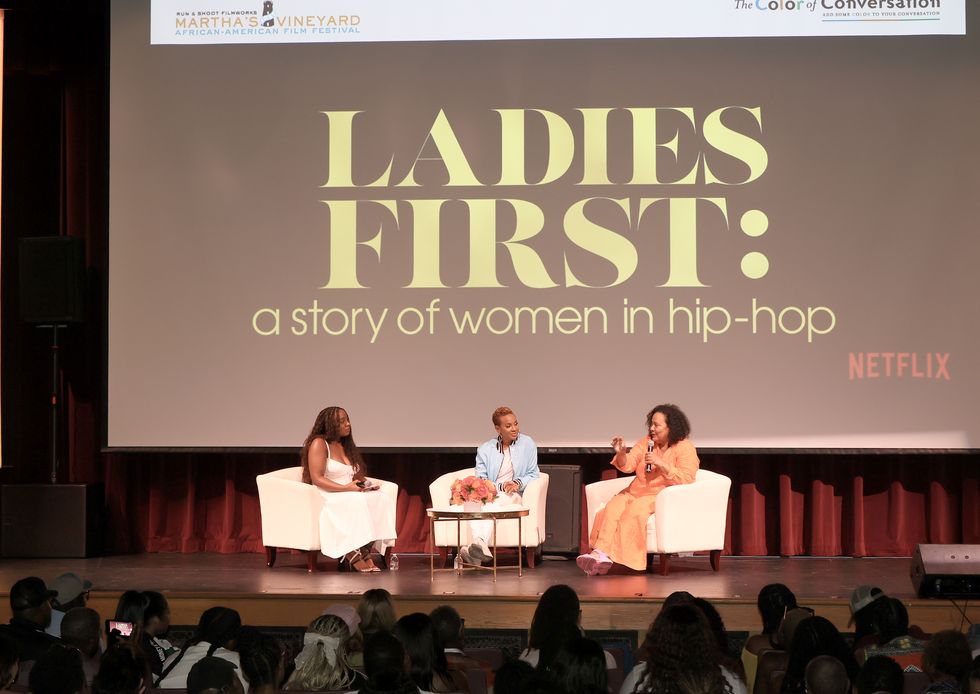

During a special screening at the Martha’s Vineyard African American Film Festival on Friday, nearly 500 guests showed up to watch Ladies First. The room erupted with applause and screams when the faces of Queen Latifah, MC Lyte, Roxanne Shanté, and countless others appeared on the ultra-large screen. At times, some women begin rapping along to tracks by Shanté and MC Lyte. It felt so good to hear these rhymes, which are cultural signifiers in their own right, clicking immediately with viewers. But, it’s the ending applause that got me. It’s almost as if every single person in the room felt how nuanced and level-headed the documentary is.

Ahead of the release of Ladies First, ELLE.com spoke with MC Lyte and Dream Hampton about Hip-Hop 50, significant hip-hop moments that impacted them both, and more.

MC Lyte, when was the first time you ever heard hip-hop?

MC Lyte: There were two encounters. One where I was unaware, and the second where I was aware. So I’ll say the second time out was in Far Rockaway, Queens. I was staying at my grandfather’s house in Hammell Projects, and there was something playing on the radio on somebody’s boombox, Supreme Allah, to be exact. It was a group downstairs surrounding this boombox. Although I was on the third floor, I skated down as quickly as I could. By the time I got down, they were playing Salt-N-Pepa’s “Showstoppers.” What I heard from the window was Eric B. & Rakim, “Eric B. Is President,” and that encounter was everything.

I think prior to that, I had heard Run-DMC’s “Sucker M.C.’s” and “It’s Like That,” and just the wave of everything that they brought in that was void of melody, but much more the boom-bap of it all, and that encounter with Rakim and Salt-N-Pepa was everything ‘cause I felt like they were speaking to me. Prior to that, I was being rapped to, which was cool, ‘cause I loved everything. [Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s] “The Message” and [Sugar Hill Gang’s] “Rapper’s Delight” and all of it sounded really like, “We’re putting on a show.” But Rakim and Salt-N-Pepa, this new phase felt like they were right in my ear talking to me. That was what really spoke to me and what really gave me the notion that I could even be an MC because I was down with talking to people and teaching and learning and having fun and all of it.

Dream, alternatively, can you tell me what Brooklyn was like around the time you moved there in 1990?

Dream Hampton: It was amazing. New York has buildings that are older than a lot of American cities, but it was wild to see people on the streets and what the fashion was. Anyway, I couldn’t afford dorms at NYU, so I ended up in Brooklyn.

[I was in] Bed-Stuy. I lived on Cambridge Place, right around the corner from Biggie on Grand, on the other corner was Daddy-O from Stetsasonic. Chubb Rock lived on St. James Place, which is Biggie’s Street, but on another block. Digable Planets lived not far away. We were all just in this universe of being young and in Brooklyn at a time that was going to later be called the golden era of hip hop. Biggie used to come to some of those classes with me.

It’s hard to look back and say, “Oh, it was grimy.” Because it didn’t feel grimy. It felt like itself. And any era you come to New York in, people are telling you you just missed the era. So when I arrived in 1990, people were like, “Oh, the ‘80s were amazing. We just had Paradise Garage and Jean-Michel Basquiat used to be walking along the streets, and this restaurant called Kansas where Andy Warhol was.” So it was as if we had just missed something.

What elements were most important for you to reflect in Ladies First?

MC Lyte: It’s really interesting because it’s taken a long time for women to have their just due in any forum. So to have not only this documentary, but others come around at this time, I think is extremely important. For me, within any of these documentaries, it’s important to have representation from not only MCs but DJs, producers, and women who work behind the scenes. I think for them to all have a voice is really important. That’s the great thing about hip-hop—no one can really have ownership over it, and everyone can get involved.

[I want to] inspire the next young woman who decides that she wants to MC, or even a young girl who decides, “I only like this type of hip-hop,” but then she’s opened and enlightened to some other element within hip-hop, and she didn’t even know that she wanted to be a journalist, or she didn’t even know that she wanted to work behind the scenes and be a director until she saw someone speak about it. So I think all in all, Ladies First is about enlightenment and finally hearing from the women themselves. I think some women who are showcased in this documentary have never spoken in this type of format, and I think it’s really important that we be able to hear the voices of the women that make up hip-hop.

Dream Hampton: I definitely was the Debbie Downer who [was] like, “Okay, we can celebrate and be triumphant, but there’s this other story that’s really sad.” So my contributions [were] like, “Hey, y’all, can we look critically at the fact that everyone went to jail?” It hasn’t always been a success. This was a women-led, crew; Culture House built out this team of amazing young women who just came into this wide-eyed, and so I had to be that auntie, like “Uh-huh girl. This is some bullshit.” These women have been abused, exploited, erased.

MC Lyte, do you feel like you all have conveyed an overall message?

MC Lyte: Yeah, that is one for sure. But it’s also, even though it’s just like your family, you’ve got many cousins, some you’ve never met, some you have heard of from afar. You heard about Auntie Lyte over there from Brooklyn and you heard about little cousin Tierra Whack over in Philly. It’s all of this blood that runs through our veins that hip-hop keeps us related because it’s a hip-hop family, but we are very different. I think for the things that we all have in common, we also have things that make us very different from one another, which is something to be lauded, because that is what made up hip-hop back in the day. You knew who everyone was because we were distinctly different from one another. I think that’s what we’re able to see also within the confines of this documentary.

How are you both feeling about Hip-Hop 50?

MC Lyte: I feel excited. I feel happy. I feel grateful. This year is a win for us all, for those who have looked to tell their story, and for those who haven’t had the opportunity like a lot of others. The further we get within hip-hop, the more benefits become available to those who are entering the game versus those who have been in it forever, being able to have those opportunities. So I think there are so many outlets [honoring hip-hop] right now, given here right now as we talk about Ladies First being a documentary that celebrates women in hip-hop, on the mic, and off the mic.

Also, you’ve got concerts that are happening that are involving a multi-layered roster that gives an opportunity for those to come see a show and see a multi-generational celebration of hip-hop, which I think is important. I think Hip-Hop 50 represents so much, but for me, it represents unity because we’re all coming together in certain places throughout the nation as well as abroad, and we’re able to show that we are unified. I think that’s a great thing to smile about, so I’m happy for the culture.

Dream Hampton: I think [for] Hip-Hop 50, if it’s not asking questions about the three major founders, [the] three kind of Mount Rushmore icons, are we talking to Afrika Bambaataa [alleged] victims? Are we talking to Russell Simmons’ [alleged] victims? Are we talking to Dr. Dre’s victims? That’s a great opportunity to do that.

Obviously, everything’s not doom and gloom. There’s so much to say about this genre of music. It’s not a culture. Culture has food. But this genre of music has persisted. Some of it’s not all good. How did we get to a point where this generation, my generation whose major kind of contribution to Black folks’ history in this country was to turn away from respectability politics, and how did we then get to policing younger artists?

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Robyn Mowatt is a writer and editor. Her work covers the intricacies of Black culture, designers of color, music, and entertainment. Mowatt has written for Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Rolling Stone, NPR Music, The Cut, Nylon, Byrdie, Bitch, Essence, Teen Vogue, Racked, Ebony, and various other web publications.