On this day in 1973, at a party in an apartment in the Bronx, New York, hip-hop was born.

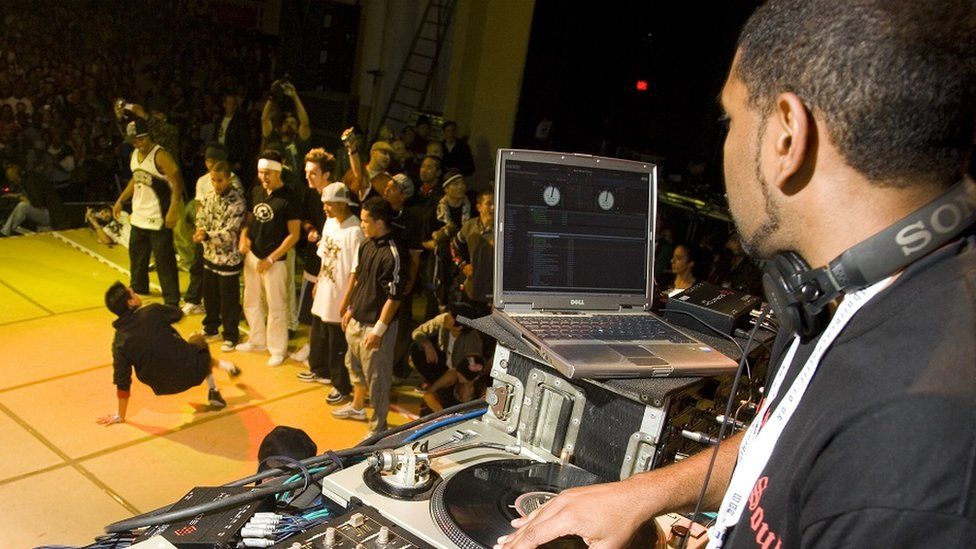

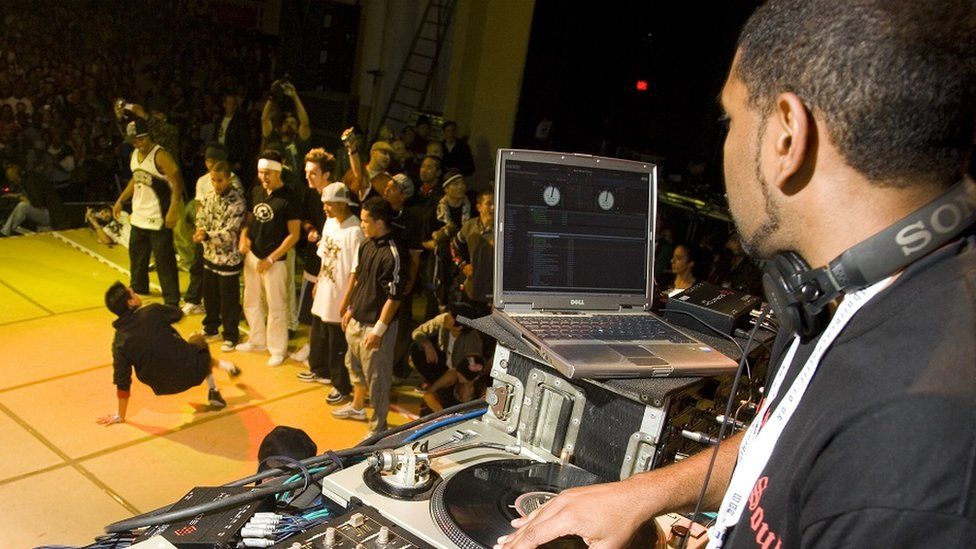

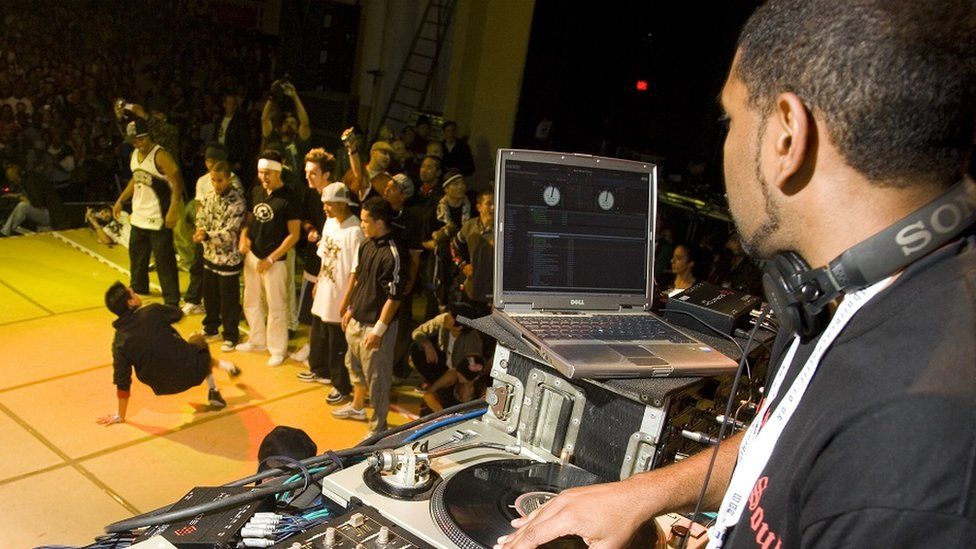

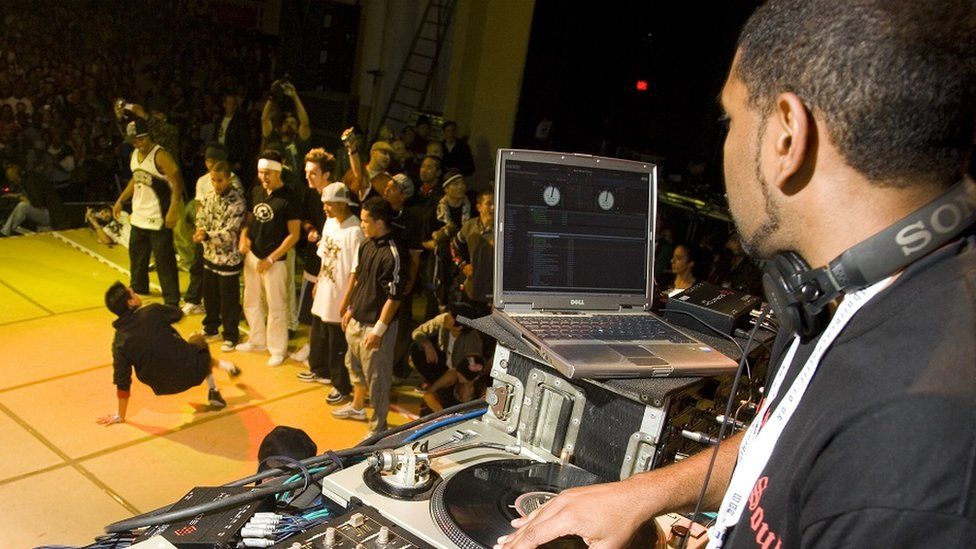

Using two turntables and a microphone, Jamaican-born funk and soul DJ Kool Herc mixed two records together – isolating and extending the kick drum beats or “breaks” – while also making rhythmic announcements over the top. The rest was history.

In reality, its roots were put down much earlier by forerunners like the Last Poets and DJ Hollywood, but 11 August 1973 became the symbolic birth date.

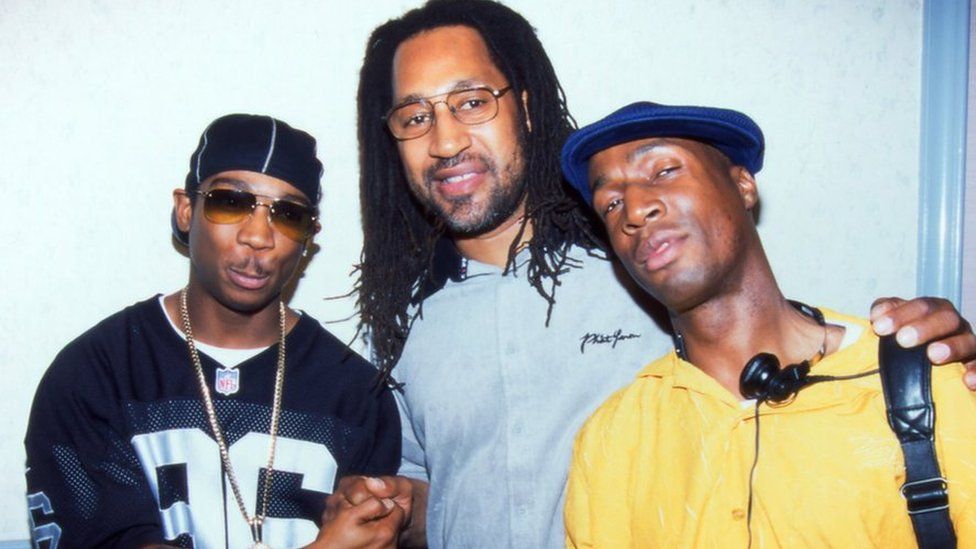

DJs soon began showing off their versatility, releasing 12-inch records on which crews of MCs would rap over the beat.

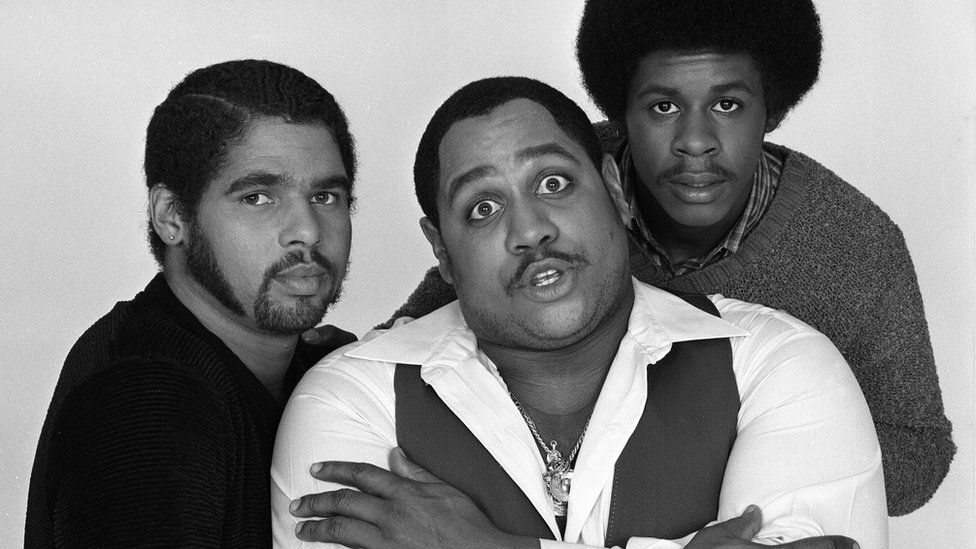

An early old school anthem emerged in the form of the Sugarhill Gang’s 1980 hit Rapper’s Delight. Considered gimmicky by critics at the time, the track – based around a sample of Chic’s Good Times – became a staple, summing up the early block party spirit of hip-hop.

It would later be covered to hilarious effect by Ellen Albertini Dow’s rapping grandmother in the film the Wedding Singer.

Rapping and mixing, along with breakdancing – a new form of street dance that grew alongside the music – and graffiti, became the four pillars of the rebellious, ground-up movement.

Moving from the street to the screen, leading New York graffiti artists Jean-Michel Basquiat and Fab 5 Freddy appeared in the first rap video broadcast on MTV, for post-punk band Blondie’s track Rapture.

As hip-hop grew, the possibilities of charting and opportunities for cross-genre collaborations grew too. Run DMC’s 1986 hip-hop reworking of Aerosmith’s rock track Walk This Way became an instant new school classic, making them the first hip-hop global superstars.

On a technical level, the likes of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five had helped to popularise “scratching” – deliberately moving a record back and forth on the wheels of steel – on tracks like The Message. And the introduction of the Roland TR-808 drum machine moved things along further.

On a personal level, signs were appearing that hip-hop was no longer the sole domain of black men. Salt-N-Pepa had a hit with Push It! and then the Beastie Boys, fighting for your right to party, scored the first US number one rap album with Licensed to Ill.

Finding its voice

Hip-hop was finding its voice, with rappers tackling political and social issues. Inspired by the Black Power Movement of the 1960s, Long Island act Public Enemy’s Fight the Power highlighted problems faced by young black people.

Nas’s track N.Y. State Of Mind – one of the few rap songs to be featured in the Norton Anthology of African American Literature – was described as providing “as clear a depiction of ghetto life as a Gordon Parks photograph or a Langston Hughes poem”.

NWA’s Express Yourself saw Dr. Dre declare, over an infectious borrowed hook, that they had been told to “forget about the ghetto, and rap for the pop charts”.

The genre was becoming a multi-edged beast, from the hard sounds of the Compton rappers to the full spectrum of offerings from Wu-Tang Clan.

Hip-hop was diversifying its sound and audience, as demonstrated by De La Soul’s debut 3 Feet High and Rising and other alternative, more spiritual “daisy age” acts like A Tribe Called Quest. Then there was Mos Def and The Roots, who were labelled “hip-hop’s first legitimate band”. A decade on, they would become household names as US TV chat show host Jimmy Fallon’s house band.

There was also a conscious movement which celebrated the experience of black women, led by the likes of Monie Love, Queen Latifah on tracks like U.N.I.T.Y, and later Lauryn Hill.

“I think by us bringing knowledge to our people, we are bringing knowledge to every other people and letting them know how we lived,” noted Hill, adding: “It’s directed at the black culture but it’s something for everyone to know.”

Golden age

The late 1980s to the mid-90s was a golden age of hip-hop, which only saw its first number one single arrive in 1990 courtesy of Vanilla Ice’s Ice Ice Baby.

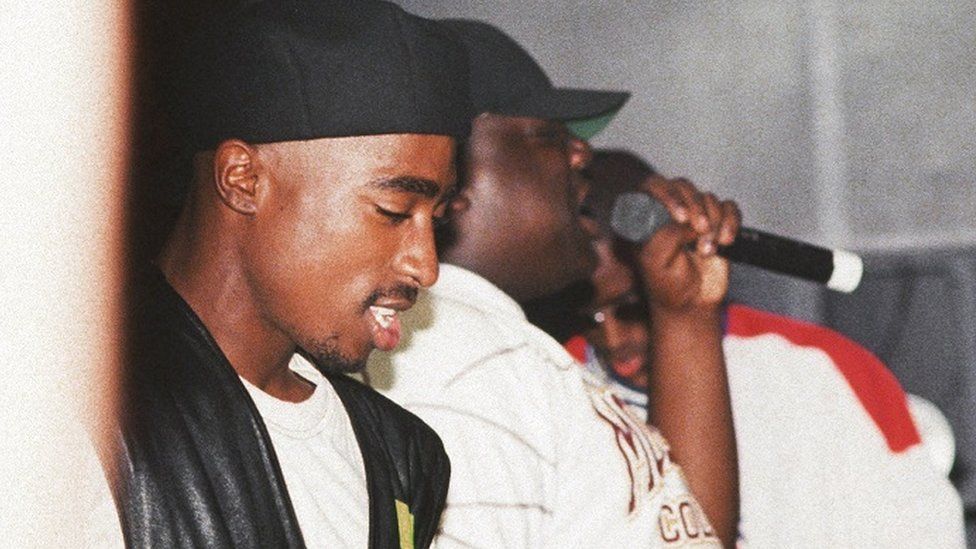

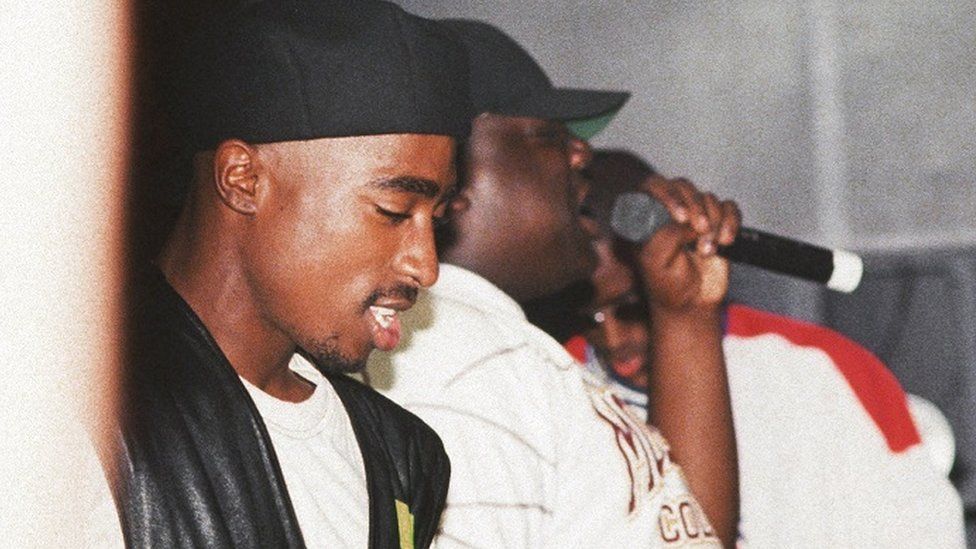

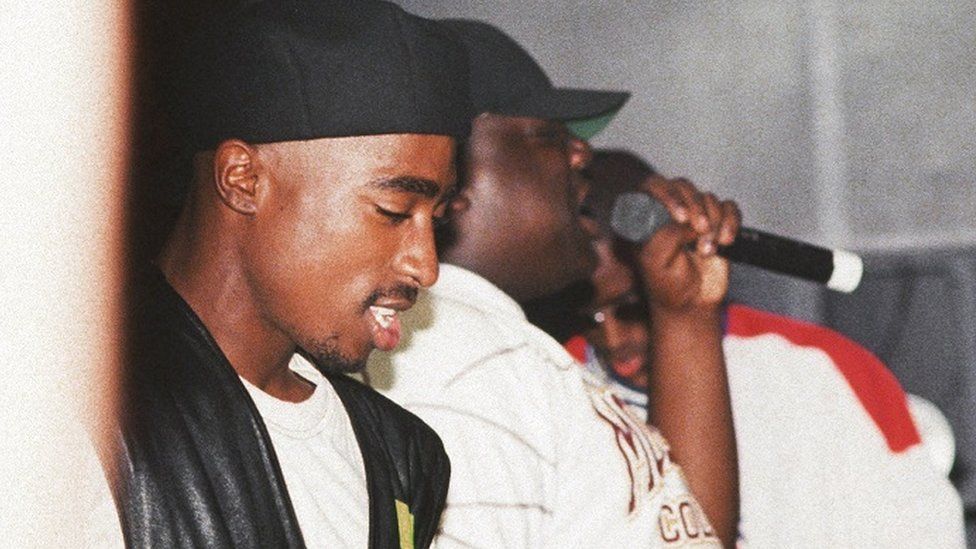

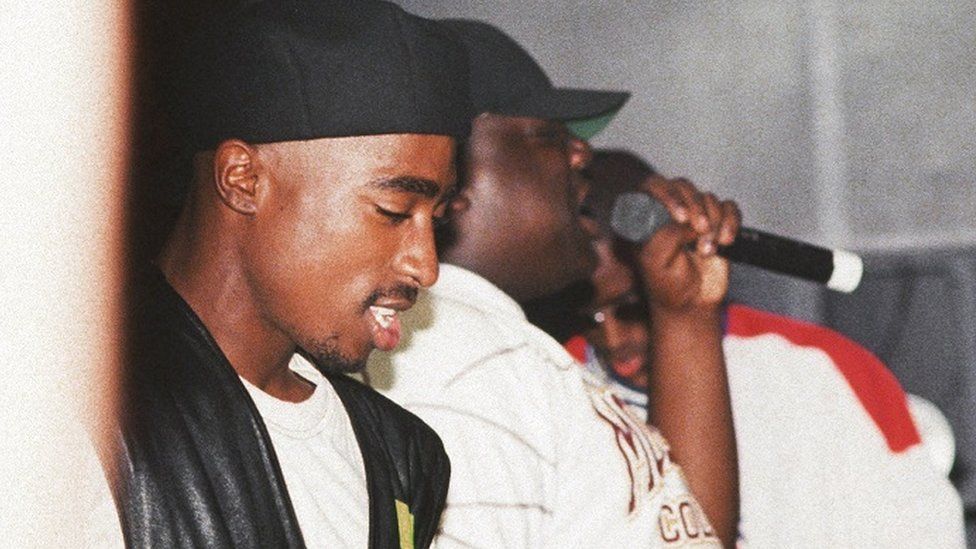

As it solidified its position as one of the biggest-grossing genres, Tupac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G. led the way with tracks like California Love, Changes and Juicy. Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg chronicled the gangster lifestyle in Nuthin’ But A ‘G’ Thang.

The sound morphed again with experimentation being led by producer Timbaland and swaggering new sensation Missy Elliott, creating the template for the likes of Nicki Minaj and Megan Thee Stallion to follow.

Fresh Prince of Bel-Air star Will Smith represented a very different side of the hip-hop coin, with popular family-friendly raps such as Gettin’ Jiggy Wit It.

History was made in 1999, when Lauryn Hill – previously of Fugees and Dangerous Minds film fame – bridged the gap between hip-hop and mainstream popular music by winning five Grammys for her deeply personal LP, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.

Her soulful rapping style went on to inspire future generations of British female rappers like Mercury Prize winners Ms Dynamite, Speech Debelle and Estelle.

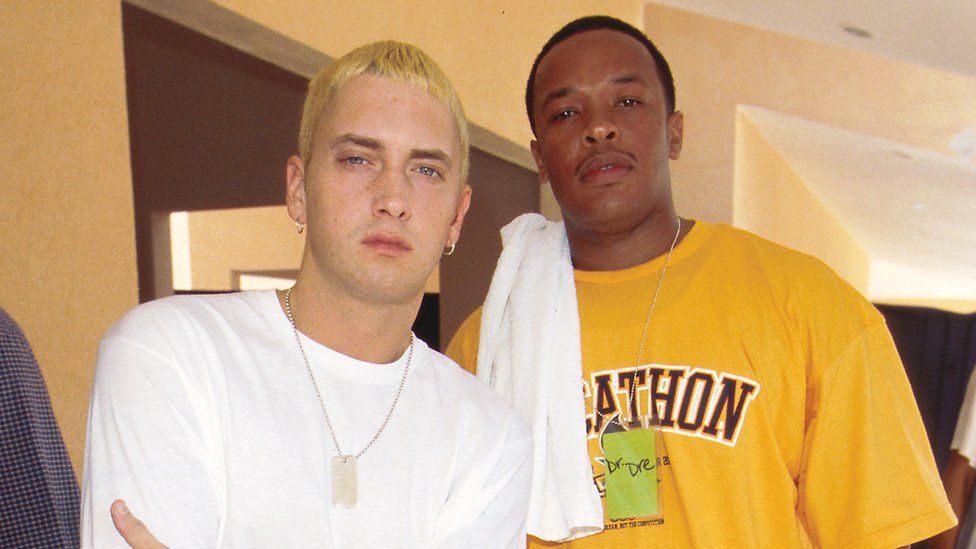

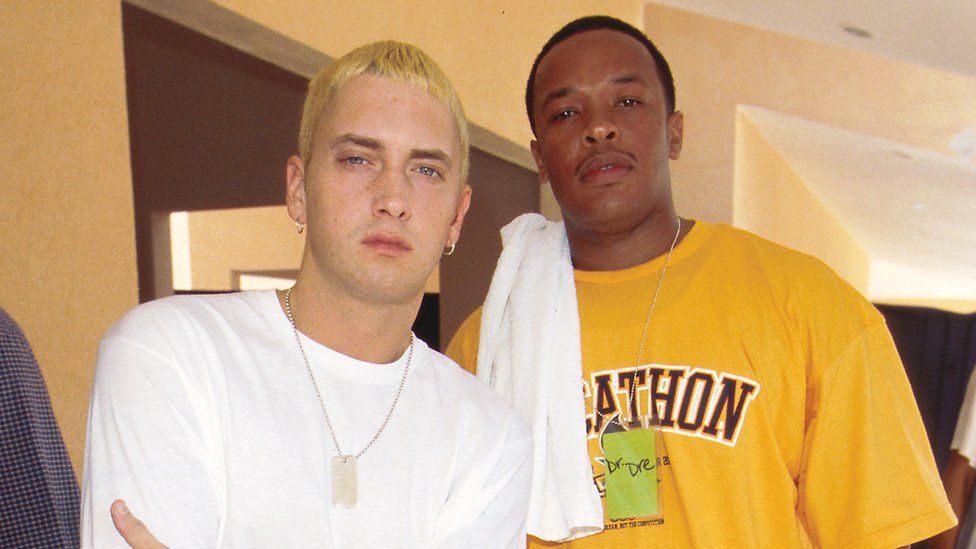

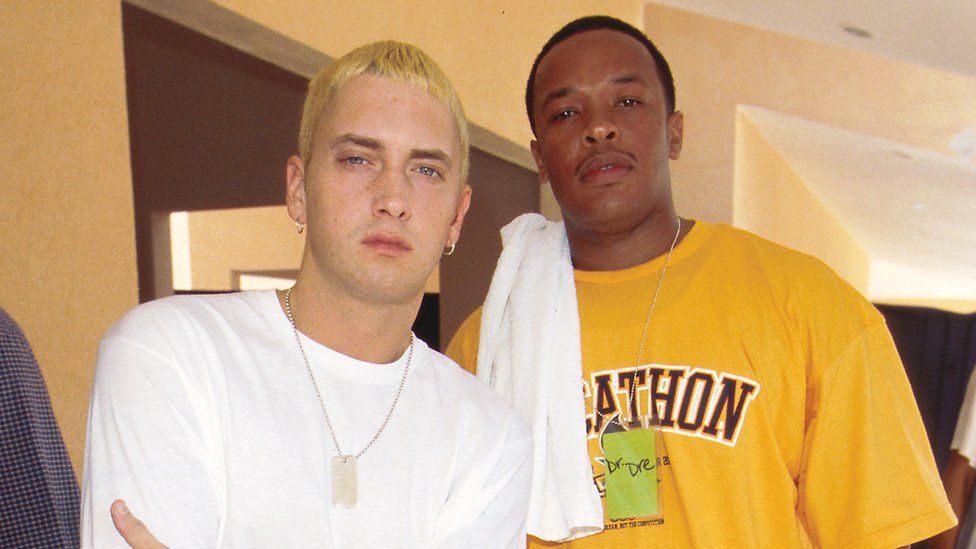

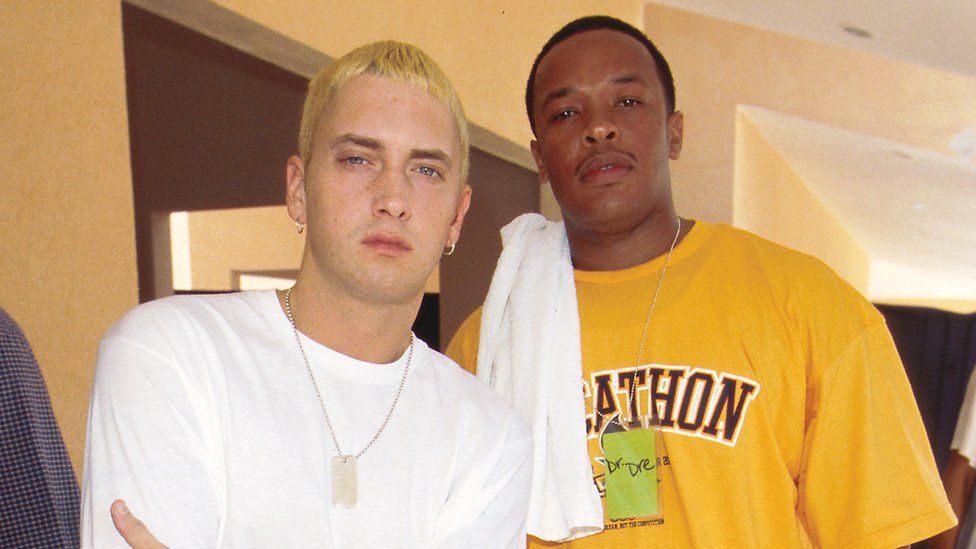

Before the millennium was up, hip-hop’s first white megastar was about to burst through. Under the mentorship of the resurgent Dr. Dre, Detroit’s Marshall Mathers III, aka Eminem, aka Slim Shady, entered loudly.

His dark-humoured, politically incorrect, quickfire rhyming style brought something new to the game, and he went on to play a version of himself in the rap battle movie 8 Mile.

Another Dre protégé, 50 Cent got Da Club pumping. “The hip part of hip-hop is youth culture”, said a young Fiddy. “I don’t think you’re supposed to have the hottest verse at 50 years old.”

Legacy

Innovation kept coming from pioneers including OutKast, Kanye West, Tyler, the Creator and Kendrick Lamar, who would turn hip-hop into an art form as the digital age arrived.

Lamar said he wanted to say “brutal” things on record that “society might not want to hear”, while “still having that connection” with listeners.

His Grammy-winning, platinum-selling 2015 album To Pimp a Butterfly delivered what became an anthem of defiance – Alright – for Black Lives Matter protesters following the killing of George Floyd. His follow-up, 2018’s Damn, won a Pulitzer Prize.

Around the same time, Canadian pop-rapper Drake became the first rap artist to be named as the Billboard Hot 100 artist of the year, thanks to his viral hit song One Dance.

Lil Nas X, one of the biggest gay rappers in a scene with a history of homophobia, set a new US chart record of 19 weeks at number one with Old Town Road.

Earlier, when hip-hop had first crossed the Atlantic, many UK acts had simply copied their US counterparts. But the likes of Roots Manuva, So Solid Crew and then The Streets, who mixed hip-hop with dub and UK garage respectively, gave rap an authentic British voice – and accent.

Trip-hop had previously seen Bristol’s Massive Attack and Portishead create a slow tempo psychedelic fusion of hip-hop and electronica.

In 2002, the BBC launched a new radio station, 1Xtra, aimed at fans of contemporary black music. The grime scene came up with it, led by London pirate radio upstarts Dizzee Rascal, Wiley and Kano, pulling together influences from hip-hop, jungle and dancehall.

A game-changing moment for UK audiences came when 99 Problems star Jay-Z headlined Glastonbury in 2008, despite Oasis’s Noel Gallagher telling the BBC it was “wrong” to have a hip-hop headliner.

Performances from Beyonce and Kanye soon followed, before Stormzy became the first black British rapper to headline the country’s biggest music festival, highlighting inequality in the justice system and the arts while on-stage. Grime collective Boy Better Know had put in the ground work at Worthy Farm, impressively, a couple of years earlier.

Having bled into UK and US street culture decades earlier, rap music had its crowning moment in 2022, taking over the Super Bowl as Eminem took the knee in support of Black Lives Matter while performing alongside Dre, Snoop and Mary J Blige.

Today’s generation of critically-acclaimed young British rappers includes Dave and Little Simz – both are in the Drake-backed Hackney gang drama Top Boy – as well as Loyle Carner. They are all adding to the sound, telling their stories in their own unique ways for new audiences.

Hip-hop’s dominance of radio play, streaming and the charts in recent years is undeniable, as well as its influence on everything from modern mainstream pop to comedy, film and fashion.

Its journey from a Bronx basement to a field in Pilton via London, Paris, Puerto Rico and the world has been a long but well travelled one.