Missy Elliott and stylist June Ambrose have yet to get their due, even though the creative team produced zeitgeist-shifting iconography, Elio Iannacci writes.Rachelle Baker/The Globe and Mail

While not nearly as unrelenting as the Barbie movie’s marketing campaign, social media shout-outs for hip hop’s coming 50th anniversary started as early as Jan 1. Music historians point to Aug. 11, 1973, as the day hip hop was born, at a party in the Bronx where DJ Kool Herc played the same song on two turntables while rapping.

Tourism boards and cultural spaces around the world have announced a slew of celebratory block parties, happenings and exhibitions to observe the substantial effects of the momentous occasion. The Ottawa Art Gallery, for example, mounted 83 ‘Til Infinity: 40 Years Of Hip-Hop in the Ottawa–Gatineau Region, an exhibit on the genre’s Canadian roots (it closes Feb. 18). Across the border, Hip Hop Til Infinity (closes Sept. 16) in New York’s Hall des Lumières displays archival footage of hip-hop pioneers in an immersive experience being sold as “a multisensory, visual mixtape.”

One of the most anticipated projects is the Netflix documentary series Ladies First: A Story of Women in Hip-Hop (premiering Aug. 9). Co-produced by MC Lyte – a Brooklyn-based artist who rapped on Sinéad O’Connor’s 1988 hit, I Want Your (Hands On Me) – it explores the ways women have shaped this enduring style of music. The film series is one of several forthcoming projects that aim to examine how female MCs and rappers fused their sounds with a vision that distanced them from hip hop’s blatantly macho roots.

Canada’s godmother of rap, Michie Mee, sees the focus on this part of hip-hop history as a reckoning of sorts. On the phone from Jamaica, the 52-year-old rapper-actor-writer, whose offstage name is Michelle McCullock, is optimistic about what she calls “revisiting the origins of the world’s most empowering music genre.” Leave it to McCullock to make such an acute reflection. As the first Canadian hip-hop star to be signed to a U.S. record label, she had no female role models to speak of when she started winning rap battles in Toronto’s Jane and Finch neighbourhood at 14.

Rapper Michie Mee in a portrait taken on May 10, 1990, at Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn, New York.Al Pereira/Getty Images

Back then, McCullock hadn’t yet familiarized herself with groundbreaking names such as Roxanne Shante, the first female rapper to have a hit record, or MC Sha-Rock, whose appearance on Saturday Night Live in 1981 inspired a generation of female musicians. Out of necessity, McCullock’s early work was mainly inspired by tracks made predominately by men.

“Public Enemy became my template,” she says, “but as a woman, I had to learn how to invent on my own.”

A key part of her success was the process of fashioning her look. For McCullock, that meant drawing symbols and adding dancehall embellishments to her sneakers from BiWay (Canada’s leading discount retailer at the time). And getting her jean jackets boned (using strips of plastic or metal to build volume and structure) to have big puffy sleeves teeming with rhinestones.

McCullock was fuelled by a love of reggae and the urge to ensure her Jamaican background was sewn directly into (or onto) her stage clothes. Keeping her career bedazzled and afloat in a male-dominated genre is something she’s writing about in her coming memoir. McCullock says that in the book, which is slated for release this year, she connects the dots on how the evolution of hip hop relates to the rise of the female MC.

“Hip hop was and still is driven by women who constantly reframe the game through style,” she says.

American music critic and author Craig Seymour views the outfits worn by female hip-hoppers in the 1980s as direct responses to the male-dominated environment they were working in. “Part of what hip hop was in the early days had to do with artists making answer records,” he says. “If a record was hot, then someone was going to come back and answer to that person through a rap of their own.

“One of Salt-N-Pepa’s first cuts is called The Showstopper and it was a response to Doug E. Fresh’s The Show. This was also happening with the fashions that these artists wore.”

Seymour, who has been tracing the roots of R&B for more than two decades, credits Salt-N-Pepa and MC Lyte as being street-style savants. “They were so ahead of the curve, using athletic wear, leather jackets, hoop earrings and crochet bucket hats,” he says, adding that this workwear can be seen as a rebuttal to the prejudices they faced and a way to further assert strength and autonomy. In other words, resistance was considered something that could be worn on the sleeve and expressed through clothing in an effort to dismantle sexist archetypes.

What McCullock considers one of the most iconic moments in hip hop’s fashion history is a work she was cast in. During the winter of 1989, she got a last-minute call to cameo in the video to Queen Latifah’s song Ladies First, featuring British rapper Monie Love. “There was an urgency on set, you could feel it. Effort was being made and it felt like an Olympic ceremony,” she says.

“It was like the beginning of the acknowledgment of the women in hip hop on a wide scale, and we were expressing ourselves through fashion. Whether someone was an extreme tomboy, into frills and dresses, into headgear or broaches or branded stuff or hoop earrings or studs – we were all making statements with these choices.”

The video splices shots of Latifah’s squad of rappers with images of apartheid attacks in South Africa and photos of Black political activists such as Madam C.J. Walker, Angela Davis and Winnie Mandela. While indisputably a feminist statement, Ladies First held court on both the radio and video charts for months against top tracks brimming with misogyny, including Tone Loc’s Funky Cold Medina and 2 Live Crew’s Me So Horny – songs that made musician Questlove describe the late eighties hip-hop scene as “a toxic masculine atmosphere with little to no elbow room for women to fit in.”

“Offering a real contrast to what was going on at the time was Queen Latifah,” Seymour says, citing the artist’s headgear, military-inspired power suits and regal fabrics as a way to cast herself in the tradition of African royalty and “anoint herself as a leader in her videos.”

Fashion historian Elizabeth Way says Latifah’s album looks from 1989′s All Hail the Queen through to 1993′s Black Reign should be seen as part of a complex legacy of women in hip hop who “embrace or reject concepts of luxury and overt sexuality.” Way was the co-curator of Fresh Fly Fabulous: 50 Years of Hip Hop Style, an exhibit at the Fashion Institute of Technology’s Museum in New York earlier this year. During her research, it struck Way that collaborative teams such as Missy Elliot and stylist June Ambrose, and Lil’ Kim, Foxy Brown and Mary J. Blige’s work with stylist and fashion designer Misa Hylton, have yet to get their due even though these creative teams produced zeitgeist-shifting iconography.

“Through these collaborations, we got to see new ideas reinventing what women in hip hop could be,” Way says, mentioning Missy Elliot’s futuristic trash-bag suit created with Ambrose. “We wanted to feature Misa Hylton’s work in the exhibition because we really wanted to shed light on stylists who haven’t received the attention they deserve.”

One of Hylton’s greatest style hits: Lil’ Kim’s red-carpet appearance at the 1999 MTV VMAs. The look included a purple wig, Steve Madden wedge heels and a Hylton-designed one-sleeve purple jumpsuit with a matching floral sequin pasty to cover the rapper’s left breast (Diana Ross fondled the flower on air). Together, Lil’ Kim and Hylton combatted respectability politics of the nineties and early aughts by reclaiming, responding to and repackaging stereotypes in a sex-positive way.

Having just finished writing a memoir as well, replete with an introduction by fashion designer Marc Jacobs, Lil’ Kim is arguably one of the most prominent women in hip hop to cross over into the luxury fashion sphere. Gen Z hip-hop stars such as Latto and Coi Leray, who have either walked the catwalk or sat in the front row for major shows during New York Fashion Week, are indebted to Lil’ Kim’s trailblazing Interview magazine cover. The image of Lil’ Kim covered in nothing but Louis Vuitton logos stirred up so much controversy in 1999 that the brand ordered a cease and desist, photographer David LaChapelle told Vice. Today, Vuitton counts rapper Pharrell as one of the fashion house’s creative directors.

Megan Thee Stallion.Rachelle Baker/The Globe and Mail

Way says Lil’ Kim and her then-nemesis Foxy Brown, a muse for John Galliano’s Dior and model for Calvin Klein jeans, proved to more than just mere fashion plates: They were fashion prophets. “They definitely illuminated the way for the women you see in hip hop today, from Nicki Minaj and Cardi B to Doja Cat and Megan Thee Stallion. The ways that Foxy and Kim embraced their bodies and curves and played with sexuality in clothes have reverberated into the videos and styles we’re still seeing.”

‘More opportunity could be given’: Toronto event to honour Canadian women in hip-hop

This includes Doja Cat’s appearance at Schiaparelli’s spring 2023 haute couture show, where she swathed herself in 30,000 Swarovski crystals; Cardi B’s two looks for the Met Gala’s red carpet this year (by designers Chenpeng and Miss Sohee); and Nicki Minaj’s famous Barbie ensemble by Vex Latex for the 2017 MTV Music Awards. The sheer amount of clothes and stylistic changes that have evolved in the scene make one wonder: What can the next generation of women offer hip hop?

“We are at this level where luxury fashion is so important that I do feel that we are going to find a drop-off,” Way says, pointing to artists who are unapologetically moving the needle away from the runway, including Ice Spice wearing throwback labels such as True Religion jeans with rhinestone-clad western belts, and SZA, who models for Crocs and opts for oversized jerseys, baggy trousers and voluminous denim. SZA’s earlier looks echo that of anti-fashion icons Lauryn Hill and Lisa Left-Eye Lopes from TLC, who played with volume and strayed from bling.

“We’re already coming back to the nineties and the 2000s,” Way says. “My guess is we’ll be going further back to an earlier era of hip hop and reinterpreting those looks.”

Fashion Mixtape

Visual outtakes from 50 years of hip hop’s stylish sovereigns

Sha-Rock

Funky 4 + 1 perform That’s the Joint on Saturday Night Live, on Feb. 14, 1981.NBC/Getty Images

After performing with Funky 4 + 1 on Saturday Night Live on Valentine’s Day in 1981, the world fell in love with MC Sha-Rock. Slaying with slouchy white boots with fringe, denim and a simple T-shirt, she broke new ground on prime-time TV.

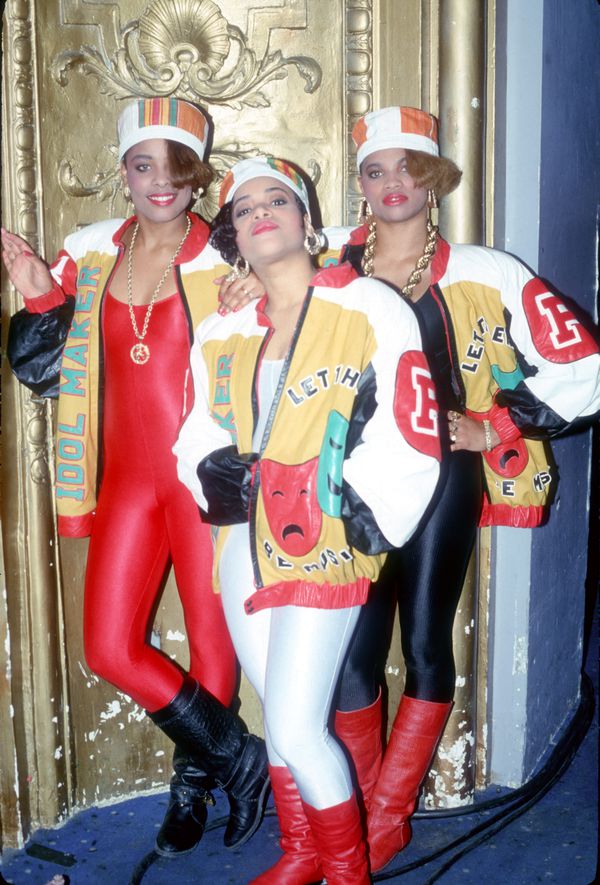

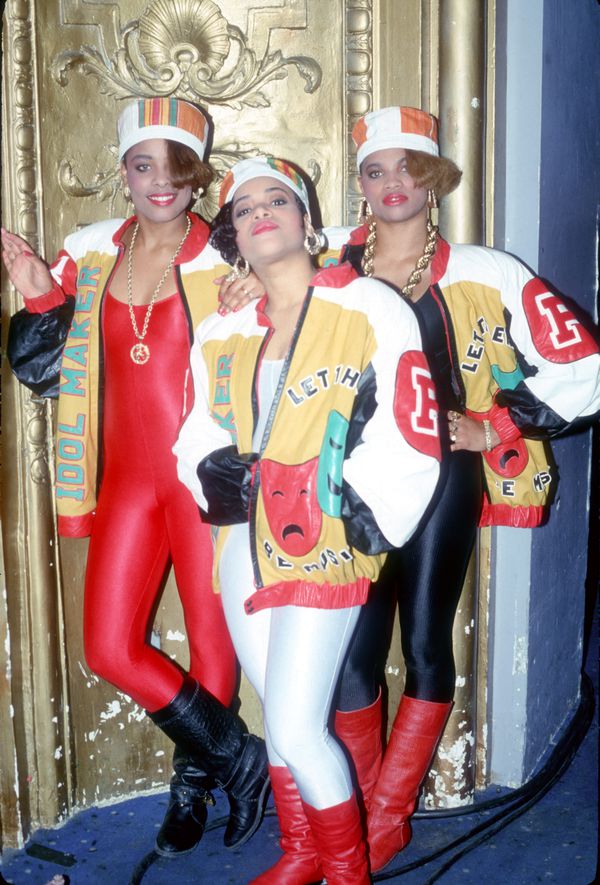

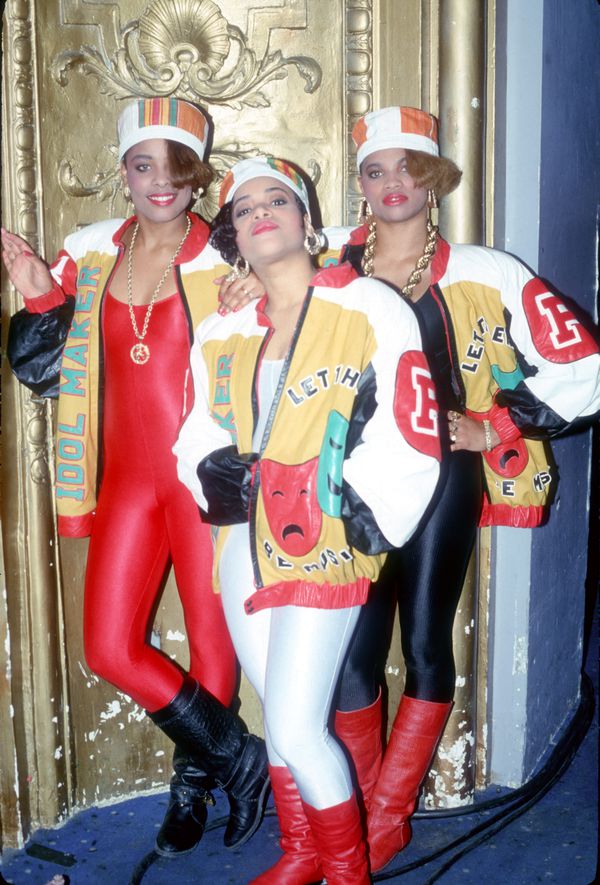

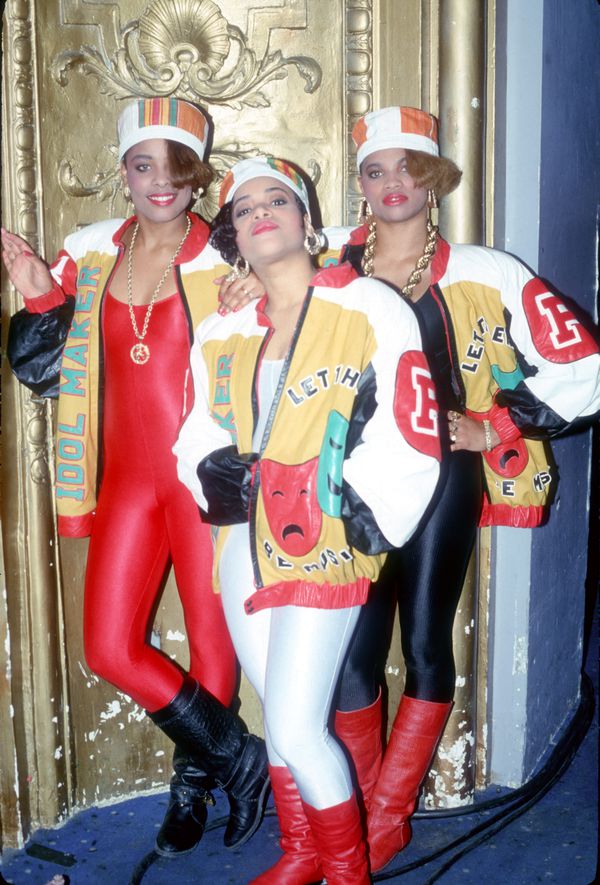

Salt-N-Pepa

Photo of Salt-N-Pepa circa 1988.Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

When Salt-N-Pepa started to sport matching Dapper Dan jackets with customized lettering, the trail-blazing rappers fuelled logomania while busting through glass ceilings. The cherries on top? Those gorgeous standout door-knocker earrings.

Queen Latifah

Queen Latifah backstage during the video shoot for Fly Girl, on June 28, 1991, in New York City.Al Pereira/Getty Images

Introducing military uniforms and ancestral headgear paired with jewellery that looked more like hardware than accessories, Queen Latifah lived up to her name during her 1989 debut album release, All Hail the Queen, styling herself head-to-toe in royal South African attire.

Lil’ Kim

Lil’ Kim, on the 1997 No Way Out tour.KMazur/Getty Images

Few hip-hop acolytes have been able to penetrate the catwalks the way Lil’ Kim did in the 1990s. Her collaborations with fashion designer Marc Jacobs, a close friend, inspired a decade of fur, metallics and sexually free designs in numerous collections for Dior and beyond. (Notably, Beyonce paid tribute to the artist, wearing a copycat of this outfit for Halloween).

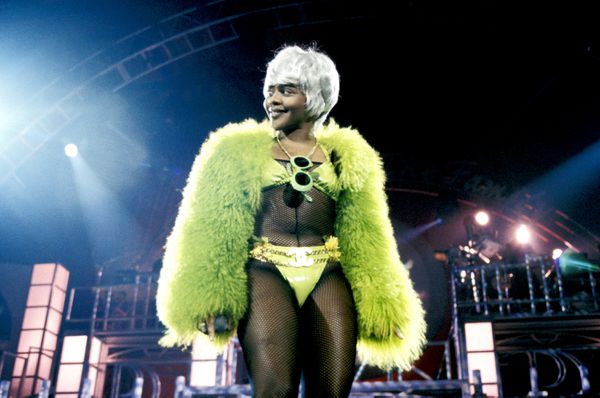

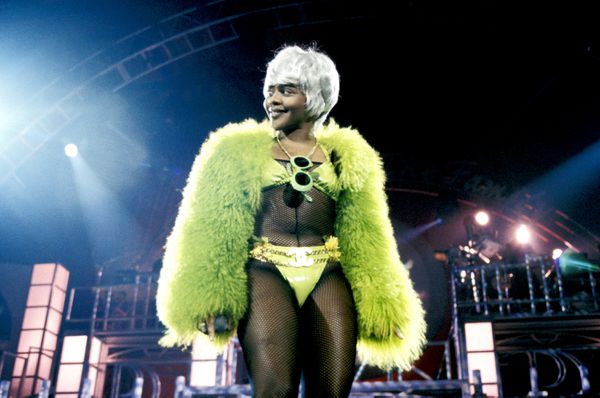

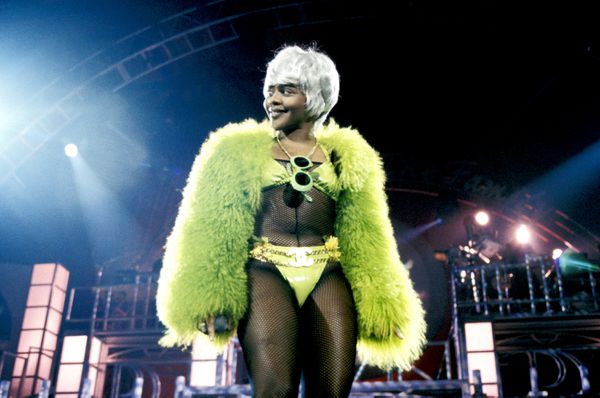

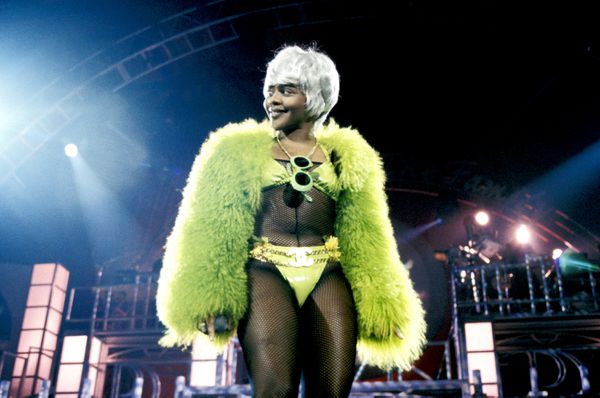

Missy Elliot

Missy Elliot performs at Lilith Fair, at Jones Beach, New York, in July, 1998.Steve Eichner/Getty Images

Teaming up with stylist June Ambrose (currently a creative director for Puma) to make a garbage bag look like a couture suit, Missy Elliot made sure her video for The Rain broke all trends into smithereens in 1997. She described the outfit to People magazine as “a symbol of power” and described the look as “hip-hop Michelin woman.”

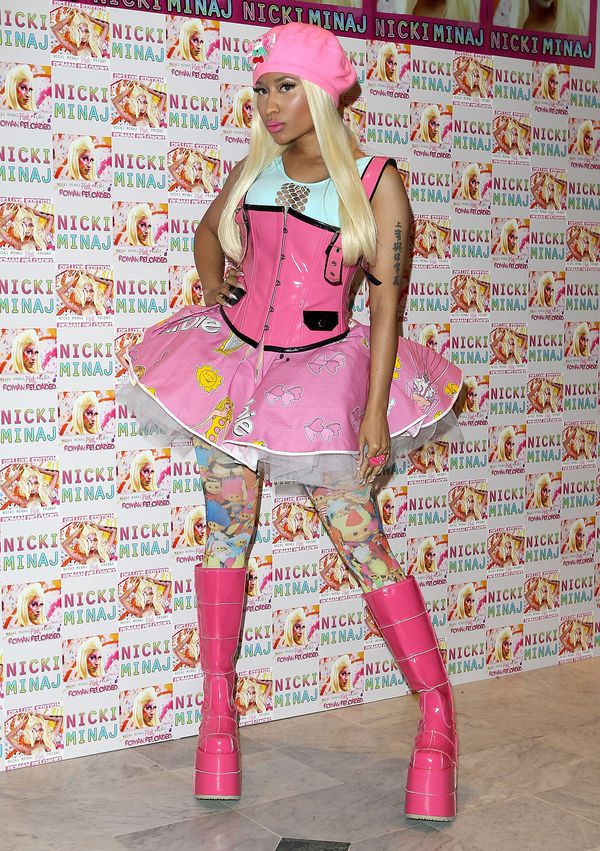

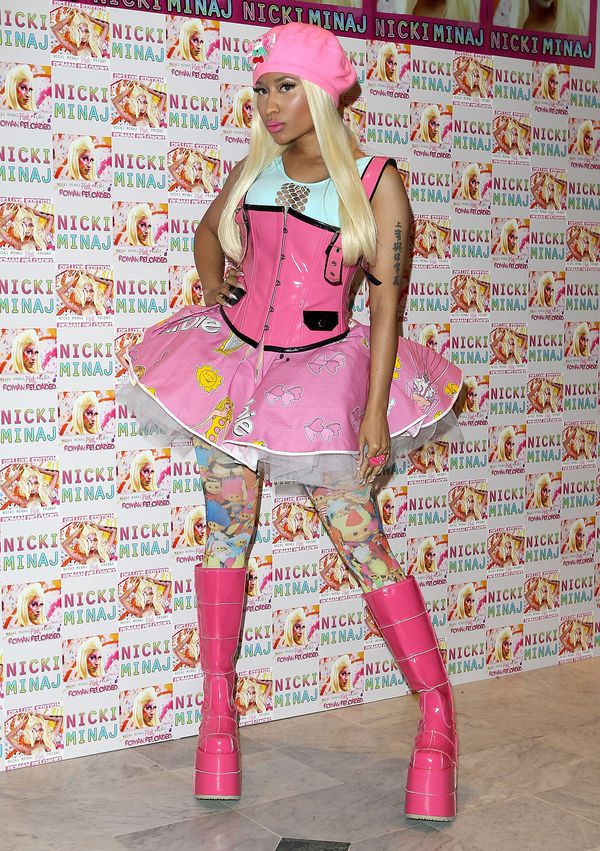

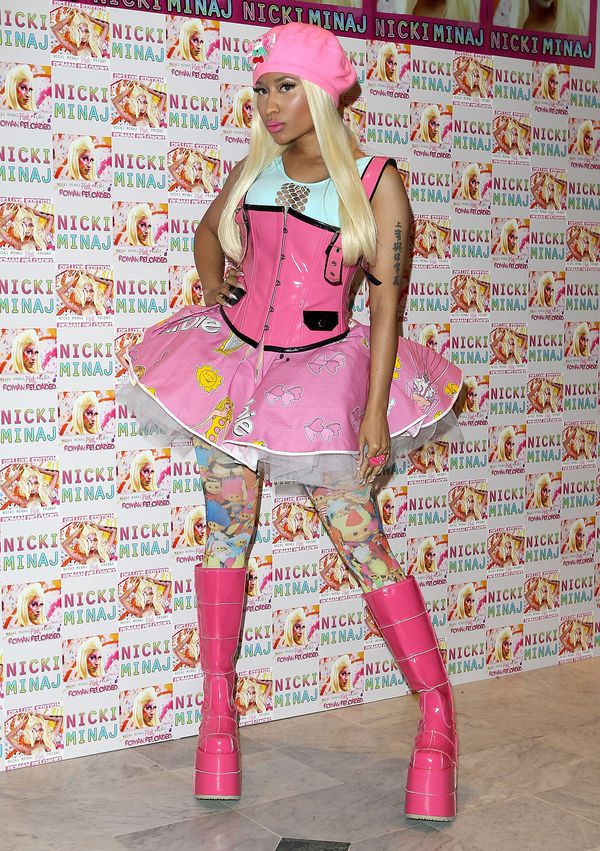

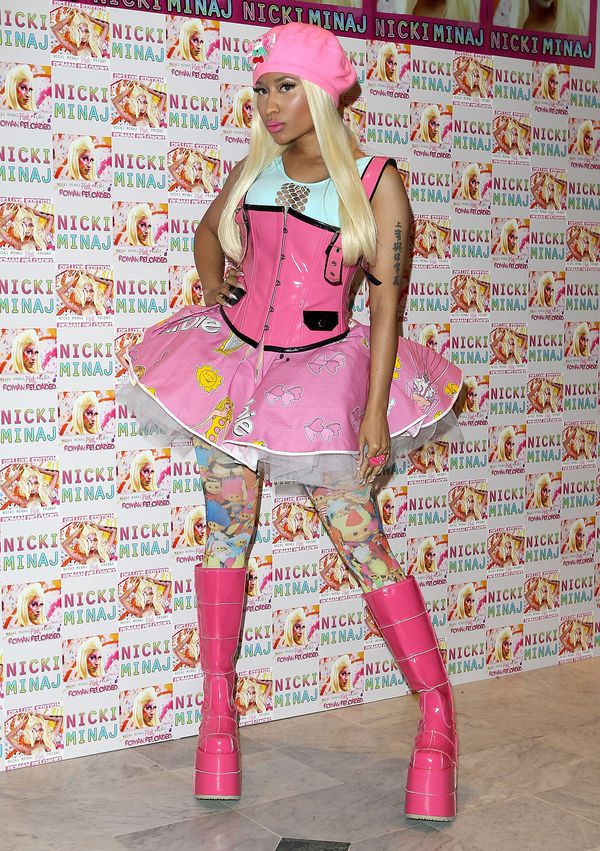

Nicki Minaj

Nicki Minaj in London, England, in 2012.Danny E. Martindale/Getty Images

Years before Greta Gerwig got the idea to turn Barbie into a feminist icon, Nicki Minaj was already turning the tables on Mattel and the world with the 2012 release of her album Pink Friday, its sister perfume and a limited-edition fashion collection called Couture by Minaj.

Doja Cat

Doja Cat attends the 2023 Met Gala.Dimitrios Kambouris/Getty Images

Meowing at interviewers on the Met Gala red carpet this year, Doja Cat’s over-the-top fashion take on Karl Lagerfeld’s beloved cat Choupette – including a US$1-million diamond on her forehead – was iconic to say the least. The Oscar de la Renta-designed look took more than six months to make and was the result of her collaboration with Oscar’s team and her creative director, Brett Alan Nelson.

SZA

SZA wearing Crocs and True Religion jeans collaborations.HANDOUT/Handout

Wearing throwback baggy denim and Crocs one day and a black illusion draped dress by Mugler the next, SZA’s evolving sense of style borrows from as many influences as her latest album, SOS. The disc’s eclectic guest appearances include singer-songwriter Phoebe Bridgers and Travis Scott.