In my time bedside stories for Hungarian children were mainly those of the Grimm Brothers, which by some ironies of nature were very grim indeed. For example: Little Red Riding Hood’s grandmother being eaten by the Big Bad Wolf or Hansel and Gretel fattened to be eaten by the Wicked Witch. By the time I learned to read, the Brothers Grimm were relegated to the bottom of a big trunk.

I chose my own reading material. To begin with, the streets to school provided many. The metal structures which protected the trees along some of the wider boulevards served also as advertising posts. For some reason, this was the way Budapest cinemas advertised. I remember that the Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex was advertised as “Love and the Scaffolds”. Another English film, Rebecca, was advertised as “A Manderley haz asszonya” (“The Lady of the House of Manderley”).

After a while I got tired of reading advertisements and, on the advice of an older and wiser friend (he must have been three or four years older than I), I went to the local children’s library to find Mathias Sandor by Jules Verne. I quickly found the Collected Works of Jules Verne translated into Hungarian in 72 volumes. They all had identical red bindings. I chose Mathias Sandor, as directed by my friend. It was the thickest volume of the lot. I took it off the shelf, made myself comfortable on the floor and started to read until I was rudely interrupted by an unappreciative member of the staff. She dragged me by the ear, put me out of the library and shut the door behind me.

Did I like to read Mathias Sandor? I worshipped it. It was the ideal book for a Hungarian pre-teenager to read. I still remember the plot. The story was set sometime in the early 1860s. The main character, Mathias Sandor, is a Hungarian aristocrat, in the process of organising a Hungarian rebellion against the Habsburgs. He believes the insurrection will be successful this time because the Austrian Habsburgs had been recently defeated both by the French and the Prussians. They might be in the mood to grant independence to the Hungarians to avoid another defeat.

The problems start when a coded letter falls in the hands of some baddies. They sell the letter to the highest bidder, who just happens to be the Austrian Secret Service. The conspirators are shot. Mathias Sandor escapes by pretending to be dead. Many years later he reappears in Europe as an immensely rich doctor, who has his own fortified island in the Mediterranean, and is preparing to avenge the death of his friends. Jules Verne dedicated the book to Alexander Dumas père, who wrote The Count of Monte Cristo in which there is the same motive for the baddies to face revenge for betrayal.

I was hooked. What next? The next one should obviously be another book by Jules Verne, I knew that, but which one? My wise friend could not help. It turned out, to my great disappointment, that the only Verne book he ever read was Mathias Sandor. I was on my own. Being methodical I chose the book on the shelf next to Mathias Sandor. I think it was Kéraban the Inflexible.

Kéraban lived in Constantinople, and he had his principles, one of which was to refuse to pay a certain tax to cross the Bosphorus. He decides instead to go round the Black Sea. Not an easy voyage. He must cross several countries, each one producing a different kind of menace. He manages well, but soon faces the same problem again when his daughter gets married on the other side of the Bosphorus.

It took me several months to devour the 72 volumes. So what did I think of them? Were all of them interesting? They were. Every story was different, but there was a leitmotif. Conflicts arise, conflicts are resolved and at the end everyone is happy, with the exception of the baddies who give the excitement to the story and who invariably receive their just deserts.

Let me mention a few of Verne’s stories. The one best known in England is Round the World in Eighty Days. Mr Phileas Fogg, a distinguished member of the Reform Club, makes a bet that he can travel round the world in eighty days. There are of course lots of setbacks, but (spoiler alert) at the end he is saved by the fact — which was a great surprise to me and to my friends — that if you go the right way around the world, you gain a full day.

A considerable proportion of Verne’s stories are about travel. There is the great story of Cascabel Cesar, who with his group of circus artists has to return to his native France, alas his travel money is stolen and the only way they can return to Europe with their props and horses from the United States is via Alaska. They manage, though not without difficulties. There is also an extraordinary travel story taking place in Russia. Mikhail Strogoff has to deliver a letter from Moscow to Irkutsk some thousands of miles away.

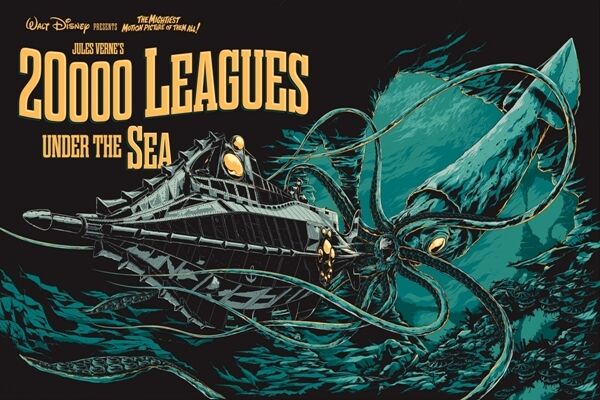

Then there are plenty of travel stories that belong to science fiction, like Captain Nemo with his vessel that could move under the sea. There is a ship that could fly, one that can reach the centre of the Earth, and there is a way to travel to the moon. To get there they need a big gun that fires the capsule with the passengers inside on its way to the Moon. The only war that comes into his stories is the American Civil war. This is in sharp contrast to the writings of his contemporary, Guy de Maupassant, who was obsessed with the Germans occupying France during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71.

So Jules Verne ignores the real war on his own doorstep . Was he a pacifist? I don’t know. I believe France’s elite was dominated at the time by the triple vow: Pour la Patrie, pour la Science, pour la Gloire (“For Country, for Science and for Glory”). It looked to me that Verne’s choice was mainly Pour la Science, not forgetting that he was a Frenchman, but having little interest in Glory. His books were not highly regarded in his lifetime. Sadly, he never made it to the Académie Française. He was dismissed as a children’s author. I think his rejection was pure Gallic intellectual snobbery.

Finally, some statistics: Verne lived from 1828 to 1905. In his day he was the second most translated author in the world — below Agatha Christie, but above William Shakespeare.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.