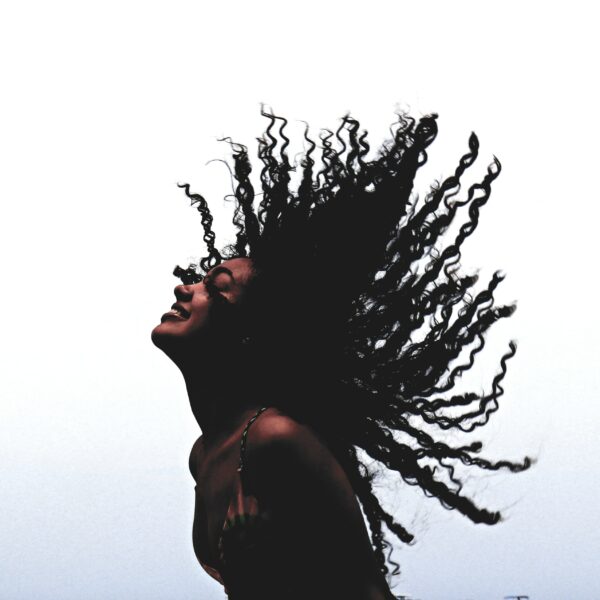

To grow up with curly hair is to feel the detriment of beauty standards weigh heavy on self-esteem. Throughout our childhoods, nobody in our households knew what to do with our curls; it’s a universal experience for people with these hair types – what do you do with it?

Esme: Placing your worth on your appearance is no stranger to anybody – especially during the teenage years – but I felt the burden of societal beauty standards and girlhood rest heavy in my stomach like lead. It was a weight that had built up throughout my life, another layer added every time someone told me to brush my hair, asked me why I didn’t straighten it, and the typical ‘birds’ nest’ comments I heard throughout my childhood – many of them from people close to me, too.

Mitali: I know what you mean. “Messy” and “unkempt” were the go-to adjectives used to describe my hair. Since that’s all I heard growing up, I subconsciously developed a resentment towards my hair without realising it. I always wished for straight hair like my mum and sister and hated that I got my dad’s curly hair. He never understood the issues I had with my hair because, growing up a man, he received very different treatment than I did. We have the same hair, but it was almost celebrated on him, while on me, it was the complete opposite.

Getting a haircut was also something I never looked forward to. I remember my sister would excitedly skip ahead to the hairdressers because they would give you a lollipop after each haircut. I would trail behind with my mum because every time I went, I would hear things like, “You would look so much nicer with straight hair,” or,” Don’t you brush your hair? It’s so tangled and hard to work with.”

I remember the first time my mum allowed me to get my hair blow-dried straight. I was so ecstatic. When I went to school the next day, I received so many compliments on my hair, and even though that was everything I wanted to hear, getting that validation for something that wasn’t really mine made me feel upset. It almost confirmed that everybody hated my actual curly hair and was just waiting for me to conform to the straight hair norm.

Esme: I had similar experiences; every day I was desperately brushing out my curls until they hung as limp and straight as possible, whipping out the straighteners despite my mum’s incessant warnings that it damaged my hair. She even used to hide the straighteners in her room to prevent me from doing it often. I thank her for it now, but teenage me was also despaired by having to go to school with my natural hair.

Mitali: I actually think it was my mum, too, who was the only person who constantly celebrated my hair. For her, I’m so thankful because learning to take care of my hair was a journey we embarked on together. We realised that my hair couldn’t be treated like her hair.

Esme: It’s treated differently in broader portrayals, too. Naturally curly hair is perceived as messy, wild, and unprofessional – depictions of witches and other evil femininities in art and media often sport some kind of untamed curly hairdo. With this comes an ever-pressing necessity to mould curly hair into something as manageable as is palatable for societal standards. This usually entails a long routine of canals worth of creams, gels, and mousses.

Mitali: I agree – I think the problem was a lack of representation of our hair type being considered beautiful. Every commercial, every movie, every TV show, and all the media I consumed displayed women with a fresh blowout and either straight or wavy hair. I didn’t even know how to style my hair for the first 16 years of my life. I opted for the same boring hairstyle from middle school till almost the end of high school.

Esme: I faced the same feelings in high school- but as soon as I became comfortable with my hair and my appearance and leaned into the beauty of acceptance and naturalism, I was faced with a new problem: corporatism.

To put it simply, curly hair is not deemed professional. The sleek, chic, not-a-hair-out-of-place appearance that is associated with femininity in business environments does not align easily with natural curls. Phenomena such as the ‘clean girl aesthetic’ also load fuel onto this fire.

Mitali: Speaking of the clean girl look, in my culture, applying oil and combing your hair is a tradition. This was a weekly routine in my household that I dreaded. My sister would be finished in around 20 minutes and always had a smile on her face at the end. When it came to my turn, my mum and I would pass each other reluctant looks as I sat down. The gap between the bristles was so thin that the comb never made it through my hair in one stroke. My mum would sit for at least an hour and brush through it in small sections to make it as painless for me as possible. But despite her best efforts, this ritual would end in tears from me.

Esme: And it’s these cultural practices that underpin the incompatibility of curly hair with professional environments; unpacking the insinuations behind it reveals prejudices. Curly hair’s reputation as unprofessional is partly rooted in colonialism. Prejudice towards non-white women by imperial means constituted ridicule through defeminization – that is, severing them from Western beauty standards. Hair played a starring role in these subordinations, and Black women’s hair especially has long been a sight of racialised politics. Weaponizing Western ideals of beauty and femininity against women to degrade their value has been used in many colonial contexts, and the residue of these imperial subjugations is woven throughout society – and the workplace.

As a white woman with curly hair, I understand my privilege in these problems passing me by. I get it easy. Being able to shake off the perceptions of corporate propriety is a more difficult feat, however, and something I imagine will surface to spit “unprofessional” at me later in life.

Mitali: Even now, I haven’t come to terms with accepting my natural hair. Most of my friends have only seen it in its natural form a handful of times because I always have it blow-dried straight. Nevertheless, it’s something I’m working on because, ultimately, it was social conditioning that made me feel this way and not an actual reflection towards curly hair.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.