From Gwen Stefani’s faux Japaneseness to the age of J-fashion TikTok, a Western fascination with the other endures across subcultures

Harajuku Girls, you got the wicked style

I like the way that you are, I am your biggest fan.

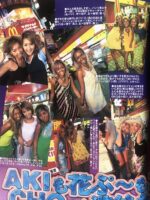

Gwen Stefani decided that she was a Japanese woman sometime in the 1990s. She went solo at the end of 2004 with Love. Angel. Music. Baby., and became immortal by surrounding herself with four Japanese backup dancers whose titular names made the album feel less like a musical project and more like performance art. Love, Angel, Music, and Baby were Harajuku girls—girls from Tokyo’s Harajuku district defined by their eccentric dress and “kawaii” demeanor—but Maya, Jennifer, Rino, and Mayuko were from Los Angeles (by way of Tokyo), Torrance, Okinawa, and Osaka, respectively. These women would become so much more than Stefani’s entourage, immortalized in perfume and plastic.

It’s doubtful that Stefani knew the social impact that would come from “I like the way that you are, I am your biggest fan,” when she wrote it, but I do think she knew that “Harajuku Girls” was more than song—it was the beginning of an empire. While asserting her own adopted Japaneseness, Stefani’s L.A.M.B. and Harajuku Lovers clothing franchises brought the country’s superfandom to America’s native land: the free market. In 2008, Newsweek reported that L.A.M.B. (the brand, sold in Bloomingdale’s and Nordstrom) had an annual revenue topping $100 million, its collaboration with LeSportsac notwithstanding. After expanding to the tween-spired Harajuku Lovers diffusion line, Love, Angel, Music, and Baby appeared alongside a doll replica of the Queen G herself—just as they did in real life, only this time as collectible perfume tops; and the American youth were Japanese, too, if just for a moment. In 2016, the Lovers would have a reprise in Kuu Kuu Harajuku, a cartoon following Love, Angel, Music, Baby, and Stefani through their adventures in the magical Harajuku City. The pop star’s lasting social impact is twofold: She taught an entire generation how to spell “bananas,” and became a cautionary tale on cultural appropriation (second only to Rachel Dolezal).

When I think of Stefani, I think of my fellow Americans. We like to think we’ve undone the racist ideal of the “Oriental,” but we’ve really just re-packaged the mystique of Japan as kawaii perfection, a utopian society based on politeness and cuteness; we are so easily influenced by Gwen, because we are Gwen. As a 20-year-old college student, I was afforded the opportunity to study Japan’s cultural development in the face of disaster—both climate and social—through traveling to various sites of the country. Where our discussions leading up to that trip revolved around texts probing at concepts of the country’s myriad historical roles in the 20th century, the trip itself became a Hello Kitty-flavored commerce once we left the island’s lesser-known Okayama Prefecture for Tokyo. It was like an analytical switch was turned off in favor of a pastel-colored bullet train with—to reference Shoshanna Shapiro of Lena Dunham’s Girls on her own fictional stint in Japan—“candy that tastes like other candy.” It is impossible to escape the realities of cultural difference with care for the Other. I understood the various sociocultural factors at play as I watched my peers reduce all of Japan to “kawaii,” and I understood how my ire can only function as that of an American tourist feigning sympathy for what I identified as inequity, what I saw as culture flattened from my own Western vantage. This is how we treat contemporary conversations surrounding hot-button issues like cultural appropriation—as Americans taking offense at the non-Western world, as if we need to stick up for the downtrodden. This is ironic given the fact that we (as a country) will gladly and silently bomb a lesser-developed one to oblivion—Laos in the ’60s, and Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan for the past nine years—while listicles on how certain hairstyles and clothing are off-limits for white people dominate modern Western media. What is it that we really care about—beyond a “person of color” aesthetic distraction from the ills of American imperialism on, well, everywhere?

“This kind of ‘cuteness’ aesthetic is a bit difficult to comprehend, because it does not fit into local categories, yet matches perfectly with a distinctly Western idea of a ‘hyper-modern, mysterious Orientalism.’”

The Western fascination with Japan today seems to be a conflation of the country’s larger cultural tableau with an idea of cuteness and docility. “I feel that ‘cuteness’ [in Japan] was never more than an ambiguous, diffused aesthetic that evoked an affective response of sympathy and care in people, young and old, male and female (and otherwise). It could be found in children, adult women, and adult men, as well as in anthropomorphized animals and other characters,” says Issac Gagné, a Japanese cultural anthropologist and Principal Researcher at the German Institute for Japanese Studies. “However, it was a Western fascination in this aesthetic—which seemed to defy both infantile cute and adult sexy—that resulted in the kind of codification and reification of ‘cuteness’ as something inherent in the Japanese subcultural landscape, and something ‘special’ to Japan.” This cuteness is special to Japan. In Tokyo, you can find Hello Kitty and Doraemon dressed in municipal uniforms plastered on buses and trains, however, the notion that these characters project a perverse, infantile sociality is a misnomer—they are symbols of a national identity that most Westerners can’t understand.

Gwen Stefani’s tagline for her Harajuku Lovers brand reads: A Fatal Attraction to Cuteness, making her American gaze plain. These people from this place are so cute, my obsession with them could kill me. From a commercial standpoint, the slogan is Stefani telling the consumer, “Die with me.” Gagné continues, “It is important to note that ‘cuteness’ as represented by Japanese actresses, cartoons, and male and female idols is not erotic or sexy for the general public in Japan. Within a highly sexualized media environment like the U.S.—a place that has relatively limited gender expressions, I would say—this kind of ‘cuteness’ aesthetic is a bit difficult to comprehend, because it does not fit into local categories, yet matches perfectly with a distinctly Western idea of a ‘hyper-modern, mysterious Orientalism.’” And, when this new-aged Orientalism is repackaged and sold as plastic perfume dolls alongside matching t-shirts and themed cosmetics, the Western idea isn’t just pervasive, it’s mobilizing an entire country to spellbind audiences into blind consumption, erasing place into ahistorical, neon-colored perfection.

In the absence of traditional categories alongside understandings of orienting (pun unintended) East from West, today’s teen girls identify rather than project. In 2023, there’s been an emergence of young girls on TikTok engaging with Japan’s gyaru subculture. To say that gyaru is “back” is inaccurate, as it works off of the assumption that it left in the first place—every Gloomy Bear sighting and decoden phone case between 2004 and present reminds us so—the subculture only existed for those who knew how to look for it on MySpace. But TikTok has reminded audiences of the tenets of gyaru that are most easily replicated in America: the chunky, sparkly, plushy, so-cute-you-could-just-puke aesthetic that says more about a Western obsession with excess than a Japanese mode of expression, or the history of a subculture. Where the culturally projected becomes insensitive, the culturally informed becomes revelatory: such is the relationship between the simultaneity of Stefani’s renewed cancellation alongside the popularity of J-fashion in the West.

Taking it back to Stefani’s self-assigned motherland, in ’70s Japan, gyaru is a transliteration of the American word gal, later used among young girls seeking refuge from the beauty status quo. Where today’s twenty-somethings had India Arie’s shiny bald head and young Avril Lavigne’s boyish silhouettes, ’90s Shibuya had its own subversive underground culture built entirely around the gyaru. Participants were typically young women challenging traditional Eastern standards of beauty by magnifying their femininity to the nth degree: bleached hair went white, tanned skin went orange, contour highlighting went unblended.

“I remember when I first got into gyaru makeup, I would try to do a droopy eye look from here all the way to here,” says Masi, one of three admins for the popular gyaru Instagram page @gyaru.gyaru.pinku. Even on Zoom, her all-pink ensemble and well-practiced Japanese pronunciation let me know that to her, gyaru is more than a mode of adornment. She traces her index finger across three-quarters of her lower eyelash line to show me what she means by the droop. “One day I came across a YouTube tutorial of a girl who started her droop way back here,” she points to the latter quarter of her eyelid. “It’s just an example of how the internet can be helpful for people who want to experiment with their style more, you have to discover what works for you. If you’re really, really into something, you’re not going to keep doing the same thing everyone else is doing, you’re going to find a way to incorporate it into your personal style.”

Masi giggles with a slight accent—for gyarus, affectation is as important as the manner of dress and accessorization. “When I first started the account, I wanted to archive old magazine pages and scans from ’90s gyaru—we’ve seen so many things fall [through the cracks] after not being archived on the internet.”

It’s this flair for chronicling what would otherwise be forgotten that underscores a majority of the community on the internet. Fellow gyaru Citrus, known as @maliciouscitrus, is similarly well-read in her own embodiment of the subculture. “With gyaru—more specifically ganguro and yamanba—I have found a space where my dark skin is trendy, celebrated, and welcomed. The style is a rebellion against colorist standards, and as a person with dark skin, I found that sentiment so empowering. When I was first researching gyaru, I had seen a video of a Japanese gal saying ‘The darker you are, the cuter you are!’ That stuck with me ever since.”

Within the gyaru community, Masi and Citrus are considered gaijin—a Japanese word that literally translates to “outside person”—meaning that their participation in gyaru is less about racial exactitude, and more about experimentation. On race, eyebrows have been raised at certain photos of young, presumably Japanese women in gyaru dress with skin artificially tanned to the point of racial ambiguity—these women are part of a substyle of gyaru called yamanba, a subculture-within-a-subculture identified by participants who wear foundation in shades so mawkishly “tan” that they verge on minstrelsy.

On TikTok, there’s a vocal faction of Black gyarus with darker skin who have reclaimed the yamanba style as their own, given that they needn’t enhance their skin tone with offensive makeup. Of this faction, Masi echoes a similar experience to Citrus’ pride in her skin tone: “To see gyaru as a desire to be dark [against] a culture telling you to wear sunscreen or carry an umbrella or stay out of the sun to stay ‘light’—that’s special. I remember thinking, Wow, I can actually try to get darker and it is a desirable thing.”

Taking on the same effect as Stefani’s early hits like “Hollaback Girl”’ that scored every mall, sleepover, and radio station—the resurgence of gyaru has just replaced the aforementioned three locations with three letters: FYP. The ’90s girls in Japan not only refused to embody beauty as they were told, they made such blatant artifice the center of their look. Somewhere between the recent deep-dive into women’s beauty norms and claims of cultural appropriation lies the renewed fascination with gyaru, and more broadly, a daring eye into the ways in which Americans cycle through Japan’s many subcultural offerings every 10 or so years.

“The capacity for Japan to serve as a canvas for projecting the desires, imagination, and fetishes of people from outside Japan is a common trope in anthropology, which is my field,” says Gagné in regard to a broader pattern of outside characterization of Japan. “I think that in terms of subcultural attraction, this is related to two primary characteristics: one is Japan’s place within the theories of modernization, and the other is what I see as a relative absence of identity politics in Japan, at least as it relates to ideologies of race, gender, sexuality, religion, politics, et cetera. Japan was the first non-Western nation to modernize, and it modernized rapidly and successfully along a different model from, say, Europe or North America.” This is essentially the making of Japan as a land of endless myth, a concept that dates back to the 17th-century French obsession with Japanese dress aptly known as Japonisme. He continues: “The relative absence of identity politics in Japan facilitates a diverse creative space for young people to explore different forms of self-performance without having to fully embrace a particular ideology or identity, and it also allows individuals to dabble in multiple forms of subcultural expression.”

Citrus and Masi both occupy unique positions in this tenuous sociological landscape: On the internet, they’ve been able to access these subcultures, and yet a strong sense of American identity politics only fortifies their relationship with their subcultural expression. Pre-Y2K Gen Z begged our moms to drive us to the mall so we could spend our entire allowance on nylon Harajuku Lovers backpacks on sale at Ross; we could barely spell Harajuku; we lived the myth Stefani presented us with—and it was fun. Citrus and Masi’s generation can’t survive with that level of unawareness, not in the age of the internet, not in the age of cultural appropriation call-outs and TikToks, but they can have fun, too. Their gyaru community does what Stefani’s previous endeavors in Japaneseness failed to: It acknowledges the Western world that informs its relationships to subcultures, rather than trying to pass off Americanized fashion editorial as an authentic, Japanese-inspired brainchild. What do we care about? We care about beauty, we care about truth. We don’t need to care about Gwen Stefani anymore.

Shortly after Stefani’s damning Allure interview, a kitschy woman at a party diverted our seemingly normal conversation five minutes in: “Biden is militarizing Japan. It only makes sense given the history there, you know…” She trailed off, distinctly afraid of making a gauche statement about Japan as an American woman—she was dressed in the manner of a working woman during WWII (somewhere between Betty Page and Betty White), which didn’t help in this scenario. This was the kind of party chat you could only find in a room full of distinctly provincial Ivy League graduates from the East Coast, so I used my West Coast sensibilities to make a brusque joke about the Fat Man, the Little Boy, and Stefani. Kitschy Woman’s mood hardened: “You know, Gwen Stefani said she was Japanese in an interview the other day.” “She’s basically right,” I said—not because I believed it, but because as an American, the most patriotic thing you can do is make yourself someone else.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.