Fifteen individuals were sentenced to jail – including sentences of up to six-and-a-half years – and ordered to pay fines by a court in China this summer as a result of their role in a 6-year, $40-million-plus criminal ring that revolved around the sale of counterfeit Rolex watches. In a decision in July, the People’s Court of Zhenjiang Economic Development Zone held that the defendants had used the Swiss watchmaker’s registered trademarks to sell fake watches, thereby, engaging in criminal counterfeiting. “The large number of people involved in the case seriously infringed on the reputation of the [Rolex] trademark and the legitimate interests of the rights holders, and disrupted the order of the market economy,” the court stated in its decision.

Severe criminal punishment, such as jail time, is traditionally reserved for counterfeiting cases “where health and safety are involved (e.g., food and electrical devices),” Schwegman Lundberg & Woessner’s Aaron Wininger told TFL. The aggravating factor here? The value of the goods. Had the watches been authentic, they would have a collective retail value of upwards of 300 million RMB ($41 million).

While the jail sentences are a noteworthy illustration of the amount of money that Chinese courts consider to warrant time behind bars, the volume of fake watches in this case is hardly surprising, as it neatly tracks with rising demand for – and the size of the market of – counterfeit goods. As of 2022, the global market for counterfeits – i.e., goods that bear a “spurious mark that is identical with, or substantially indistinguishable from, a registered trademark” – reached an estimated $4.2 trillion, with luxury/fashion goods making up a significant portion of that total. That figure is way up from the $30 billion market that counterfeits comprised back in the 1980s and is expected to grow even further.

Counterfeiting continues to be a “booming business,” according to Robert Handfield, a Professor of Supply Chain Management at North Carolina State University, with “many companies losing significant revenue to counterfeiters who sell fake products that look identical to the real thing.”

Despite the burgeoning market for authentic luxury goods, which has sent stock prices for the likes of LVMH and co. soaring over the past decade, companies view counterfeiting and infringement activities as capable of having “an immediate adverse effect on revenue and profit,” and over time, as capable of “damag[ing] the brand image of the products concerned and erode consumer confidence.” That is how LVMH characterized counterfeits it in its 2021 Universal Registration Document. In a more-recently-filed trademark counterfeiting lawsuit, counsel for the group’s largest brand, Louis Vuitton, asserted that in order “to combat the indivisible harm caused by [counterfeit sellers] … each year Louis Vuitton expends significant monetary and other resources in connection with trademark enforcement efforts, including legal fees, investigative fees, and support mechanisms for law enforcement.”

The French luxury goods group – which owns upwards of 75 brands, including Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Loewe, Tiffany & Co., Bulgari, etc. – revealed in the same 2021 filing that it devotes “around 40 million euros” per year (as of 2021) to funding internal and external anti‐counterfeiting activities. LVMH elaborated in its 2022 filing, stating that its Anti-Counterfeiting Department – in coordination with each Maison’s legal department – “determines and implements anti‐counterfeiting and anti‐gray‐market policy on behalf of 26 of the Group’s Maisons for both offline and online markets. Its worldwide efforts aim to dismantle criminal networks that breach intellectual property rights and damage the reputation of our brands.”

While LVMH may be relatively unique in its size and the prowess of its brands, it is not uncommon for luxury goods companies to routinely allocate sizable sums to combatting counterfeits in order to “protect both consumers and [themselves] from the adverse effects of confusion and erosion of the goodwill embodied in” their brands. Just last week, Gucci initiated a trio of lawsuits against Sam’s Club, Century 21, and Lord & Taylor, arguing that their sale of counterfeit goods “directly compete[s] with Gucci’s products” and that their “unauthorized acts … have caused and will continue to cause irreparable damage to Gucci and its business and goodwill,” forcing Gucci to take legal action.

Super-Charging the Counterfeit Market: Cultural Shifts & Super Fakes

Even with companies’ hefty budgets for brand protection efforts, the market for fakes continues to rise, driven by a confluence of factors – from the increased availability and ease with which these goods can be purchased to an overarching evolution in how consumers have come to view counterfeits. Put simply, the counterfeit game is changing.

The days of low-quality knockoffs are not over, but at the same time, a new category of counterfeits – “superfakes” – has garnered headlines and interest from consumers. These are counterfeit goods whose tell-tale signs of inauthenticity are virtually “undetectable to human eyes,” as the New York Times put it in June. Referring to the rise of “fantastically realistic counterfeit purses” – aka “superfakes” or “unclockable reps,” the Times reported that these bags seem to be constructed from “the same gleaming materials as the ‘original [bags].’” And they command prices that reflect their heightened quality: a “superfake” Hermès Birkin bag can set you back more than $2,000.

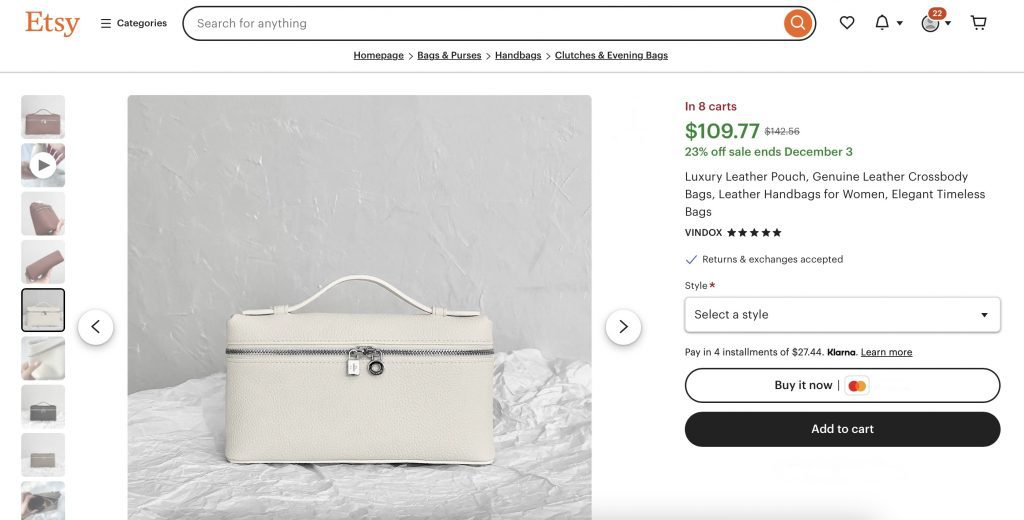

In addition to the rising quality of the counterfeits in the market, which has reportedly tempted traditional counterfeit buyers and more-deep-pocketed consumers, alike, the sheer ease with which consumers can nab counterfeit goods is notable. Fakes can be ordered by and shipped to consumers – relatively discreetly – from a wide range of marketplace sites, such as DHGate, Amazon, Etsy, etc. The pandemic had a hand in super-charging this, with a 2022 survey conducted by European Union Intellectual Property Office (“EUIPO”) finding that the percent of consumers who were intentionally purchasing counterfeit goods – including counterfeit luxury goods – was on the rise.

Not only was the surge in intentional counterfeit purchases driven by “the widely documented increase in online shopping during the COVID-19 pandemic,” according to the EUIPO, the popularity of “dupe influencers” likely has had a hand in boosting sales of counterfeit goods online. The rise of influencers dedicated exclusively to helping their followers find “high quality” counterfeits comes hand-in-hand with a cultural shift that has chipped away at the shame of buying and toting fake bags. “The taboo of wearing counterfeit designer [goods] still carries a certain weight in some cultures,” Buzzfeed’s Ade Onibada stated last year, but there is a strong current of normalization of fakes among consumers.

At least some of these consumers see their purchases as “a small act of defiance against an industry that has thrived on scarcity and exclusion.” Chances are, the enduring price hikes being enacted by luxury brands are also fueling feelings of discontentment among at least some counterfeit-buying consumers.

Finally, others have expressed interest in the hunt for what they view as a bargain; hardly an untested tactic, the consumer desire for a treasure hunt has turned off-price chains into multi-billion-dollar revenue generating giants – albeit, instead of marked-down designer wares, the hunt here is for realistic “dupes.”

New Terminology & Fast-Fakes

The change in tune among younger consumers, in particular, is also being reflected in how counterfeit goods are characterized. As we first reported back in 2021, consumers were readily referring to counterfeit – or otherwise infringing – goods as “dupes,” co-opting a term previously reserved for products that are inspired by others but nonetheless, above-board from an intellectual property perspective. This seems to be a nod to the fact that the narrative is changing: “It’s becoming more and more socially acceptable to have replicas,” said Charles Olschanski, CFE, CFI, senior director of global protection for the Americas and global brand protection for Tiffany & Co. told Loss Prevention. “It’s become a trendy thing.”

Beyond that, the speed at which the digitally-connected fashion industry operates – paired with the fleeting nature of trends, including when it comes to handbags – has pushed at least some consumers away from “investing” in one authentic bag that they will carry for seasons. Instead, they are opting for a bigger, seasonal collection of fakes. And the market is willing – and able – to meet such sped-up demand. Hunter Thompson, who oversees the authentication process at the luxury consignment site the RealReal, told the Times, “It’s gotten to the point that you can see something in season replicated within that season.”

Taken together, this makes for a perfect storm for counterfeits.

The Bigger Picture

Not limited to arrests in China, an even more recent bust sheds a clear light on the state of the market for fakes. On November 15, U.S. authorities announced “the largest-ever seizure of counterfeit goods” in U.S. history. “As alleged, the defendants” – two New York-based individuals – “used a Manhattan storage facility as a distribution center for massive amounts of knock-off designer goods,” including nearly 220,000 counterfeit bags, clothes, shoes, and other luxury products bearing the trademarks of Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Marc Jacobs, Hermès, Burberry, and Prada, among other brands. Had the goods been authentic, they would have been worth $1 billion.

The “groundbreaking [seizure] underscores the unwavering commitment of Homeland Security Investigations New York in the fight against intellectual property theft.” It also, of course, provides the latest reminder that the robust market for fakes is going strong. And thanks to an array of factors – from rising prices to changing consumer sentiments, it is potentially stronger than ever before.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.