Sign up for The Brief, The Texas Tribune’s daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

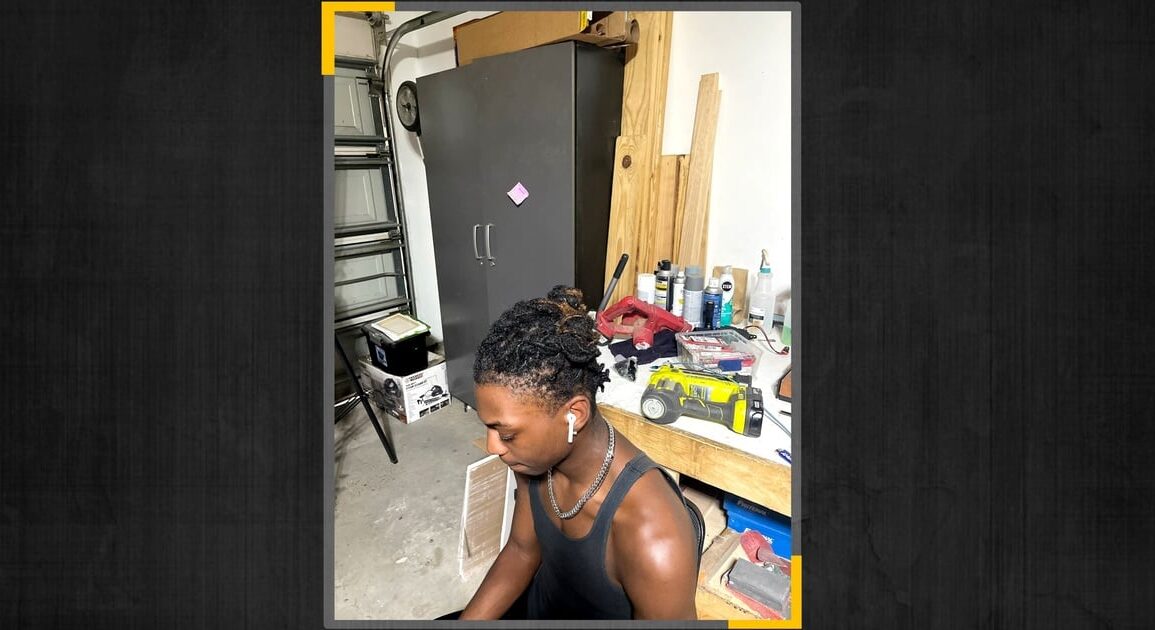

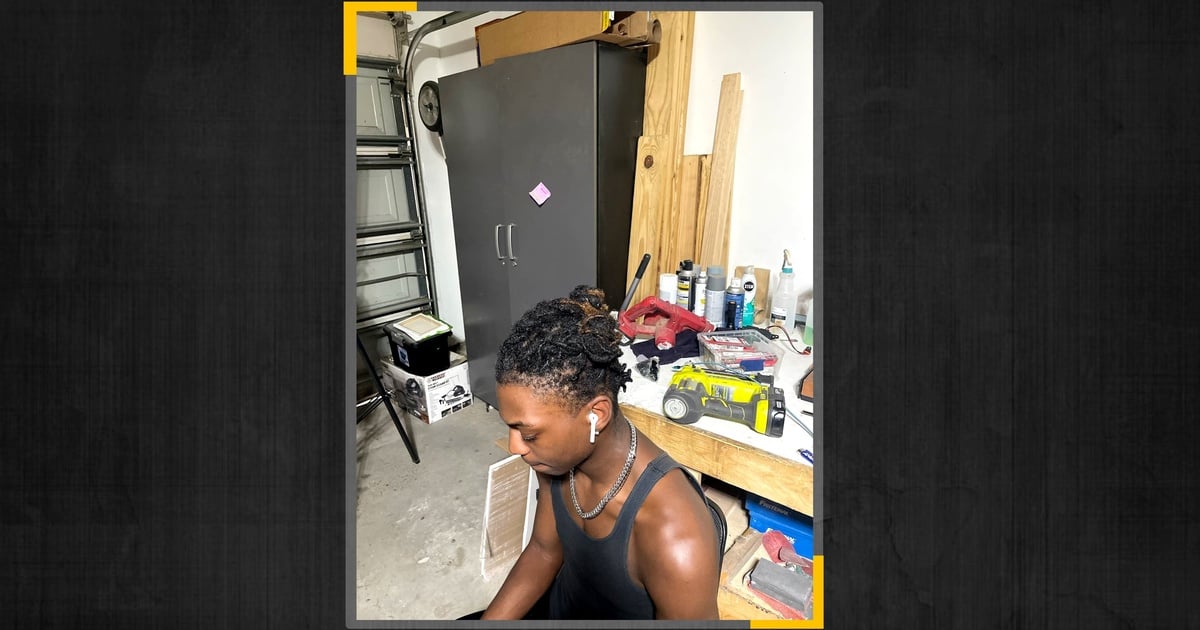

At 18, Darryl George has spent most of his junior year at Barbers Hill High School separated from his classmates, sentenced to a mix of in-school suspension or class at an alternative education campus. He’s allegedly denied hot food and isn’t able to access teaching materials.

His offense: wearing his hair in long locs.

Since the start of the school year, George and Barbers Hill school officials have been locked in a standoff over his hairstyle — and whether the district’s dress code violates a new state law that prohibits discrimination based on hairstyles.

George, who is Black, says in legal filings that the district’s monthslong punishment has demeaned him and impeded his education.

“I am being harassed by school officials and treated like a dog,” George said. “I am being subjected to cruel treatment and a lot of unkind words from many adults within the school including teachers, principals and administrators.”

Barbers Hill school officials, though, have refused to budge, accusing George and his mother of intentionally violating district rules in order to financially benefit in court. And they’re standing by their policy.

“Our military academies in West Point, Annapolis and Colorado Springs maintain a rigorous expectation of dress,” Superintendent Greg Poole wrote in a full-page ad in The Houston Chronicle. “They realize being an American requires conformity with the positive benefit of unity, and being a part of something bigger than yourself.”

On Thursday, a Texas judge ruled that Barbers Hill can continue punishing George.

Attorneys for the school district and George faced off in a short trial before Judge Chap B. Cain III, who decided the district’s dress code policy does not violate Texas’ CROWN Act, a law that went into effect on Sept. 1. The CROWN Act — an acronym for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair — outlaws discrimination on the basis of “hair texture or protective hairstyles associated with race.”

The Barbers Hill school district’s dress code says male students’ hair cannot extend below the eyebrows, earlobes or the top of a T-shirt collar. Male students’ hair also may not “be gathered or worn in a style” that would allow the hair to fall to these lengths “when let down,” the policy states. George wears his hair in a twisted style at the top of his head. According to legal filings, he considers them an expression of cultural pride and refers to them as locs. The difference between locs and dreadlocks is currently the subject of a larger cultural discussion.

The CROWN Act does not include language about hair length, but the lawmakers who wrote it said before Thursday’s ruling that the law nonetheless protects George’s hairstyle because it prohibits districts from punishing students who wear their hair in particular styles, including locs.

“Those styles are protected however the style is worn,” said state Rep. Rhetta Bowers, D-Garland, who authored the bill. “When people in our culture lock their hair, they are locking it to grow.”

The standoff between George and the Mont Belvieu school district has caught nationwide attention and reignited a fight over hair discrimination that took hold in Texas in 2020. Then, another Black student at Barbers Hill High School who wore locs was told that he could not attend his graduation ceremony unless he cut his hair. That students’ cousin, a sophomore at the time, was also sent to in-school suspension because of his hair length.

The two students’ families filed a federal lawsuit contending that the policy was discriminatory. A judge issued a preliminary injunction blocking the school district from enforcing the dress code policy. Litigation in that case is ongoing, and the judge’s narrow decision did not prevent the district from keeping the policy or enforcing it on other students in the future. But it did play a role in Texas signing the CROWN Act, which has also passed in 23 other states. That new law is what’s at the center of Thursday’s trial.

Lawmakers and civil rights advocates argue that Barbers Hill’s policy is rooted in stereotypes and anti-Black prejudice. Poole, the superintendent, declined an interview with The Tribune. In an email sent through the district’s spokesperson, Poole suggested that the George family’s lawsuit was motivated by money. He said George’s mother, Darresha George, moved her son to Barbers Hill from an adjacent district that did not have a hair policy.

“His guardian understood fully what our rules and regulations were yet still enrolled and shortly thereafter we hear from an activist and a lawyer,” Poole said. “His lawyer has made it clear that this is about money.”

Darresha George, Darryl George’s mother, filed a federal lawsuit in September against both the Barbers Hill school district as well as state officials. She argues that the district is violating federal civil rights law and the CROWN Act and that Gov. Greg Abbott and Attorney General Ken Paxton are failing to enforce the CROWN Act. George seeks compensatory damages “in the amount approved at trial” in that suit, whose litigation is ongoing. The case heard Thursday was a separate case that Barbers Hill officials filed in state court asking a judge to rule that they are not violating the CROWN Act.

George’s lawyer, Allie Booker, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. The George family could not be reached directly.

Barbers Hill is not the only school district in Texas whose dress code policies have been called into question. A report this month from the American Civil Liberties Union of Texas found that during the 2022-2023 school year, 26% of school districts had dress codes with boys-only hair length rules. And 7% of surveyed districts explicitly prohibited hairstyles and textures associated with race. The survey was completed prior to the CROWN Act going into effect.

The report says that boys-only hair-length rules date back to the 1960s, when school districts tried to make boys look “clean-cut” amidst a growing trend of men wearing longer hair. Such policies “shame and penalize students for simply showing up in the classroom as their authentic selves,” the report states.

“The idea behind them is to maintain order and to encourage a very specific kind of understanding of how students are supposed to show up in the classroom,” said Caro Achar, one of the authors of the report. “But the impact is that it’s discriminatory, and students feel left out and targeted.”

Hair discrimination dates back to at least the 19th century, when enslavers required Black women to cover their hair or to emulate Eurocentric beauty standards by straightening their hair. To challenge this, natural hair has been used as a symbol of Black power and identity, particularly during the Black power movement of the 1970s and 1980s.

Still, social pressure to conform to white beauty standards persists. One recent survey found that more than 20% of Black women ages 25-34 have been sent home from work because of their hair. The survey also found that Black women with coily or textured hair are two times as likely to experience microaggressions in the workplace as compared to Black women with straight hair.

Rodney Ellis, a commissioner in Harris County and the sponsor of a resolution to enact the CROWN Act there, recalled his three daughters straightening their hair to adapt to their environment.

“Sometimes I would try to push them to conform to a certain style that I thought was appropriate,” Ellis said. “Over time, I grew to appreciate the particular challenges that Black women and Black girls have to go through.”

The Harris County Commissioners Court approved the CROWN Act in 2021, becoming the first county in Texas to adopt the measure. Ellis said he was disgusted to learn about what is happening at Barbers Hill, and he viewed the district’s efforts as part of a larger national strategy to curb anti-racist education efforts, such as by limiting how slavery and history are taught in public schools, or by restricting certain library books.

“When young students are punished for simply expressing their cultural identity through their hair, it sends a chilling message that their heritage is unwelcome and that they do not belong,” Ellis said.

In an affidavit filed in January, George said that his mental health as well as his grades have suffered since he began getting punished for his hair at the start of the school year in August.

In a statement before Thursday’s trial, Superintendent Poole said the district looked forward to having the court clarify the meaning of the CROWN Act.

“Those with agendas wish to make the CROWN Act a blanket allowance of student expression,” Poole said. “Again, we look forward to this issue being legally resolved.”

We can’t wait to welcome you to downtown Austin Sept. 5-7 for the 2024 Texas Tribune Festival! Join us at Texas’ breakout politics and policy event as we dig into the 2024 elections, state and national politics, the state of democracy, and so much more. When tickets go on sale this spring, Tribune members will save big. Donate to join or renew today.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.