A listing in the Guinness Book of World Records was followed by a years-long battle over ownership of the Ophir Collection.

By Brandon Kochkodin, Forbes Staff

It’s possible there’s a curse attached to the Ophir Collection, a trove of 43 precious gems that an overheated appraiser once estimated to be worth $3.2 billion.

If there’s truly a curse, it wouldn’t be the kind from old-time pirate lore that rains damnation on whoever possesses the gems. More like a spell that causes moral compasses to spin, sparks quarrels over ownership and sows the chaos of contradictory court rulings while offering a peek into the souls of men clawing each other to acquire precious stones.

At the heart of the confusion lies a lingering mystery: how much is the Ophir Collection really worth? Even those who would profit from a high valuation scoff at the $3.2 billion appraisal from May 2019. As in any market, sale price is the true marker. But as Seth Rosen, co-owner of the International Gem Society and a former investment banker, told Forbes, that’s tough to come by. “There’s a saying in the gem world,” Rosen said. “‘The gem is rare, but the buyer is even rarer.’” It turns out that an asset that has never been sold and hence can be valued at just about any amount can come in handy when, say, its owner is looking for collateral to post against a loan. In other words, a big part of the value of the Ophir Collection is that it has no definitive value. It’s priceless, in the sense that it has no price.

The story of the Ophir Collection begins with an MIT MBA named Dion Tulk, who comes from a Canadian family of gem collectors. Tulk picked up his fascination at earth sciences summer camp in Ontario when he was nine years old. As an adult he spent years traveling the world searching for the gems that became the Ophir Collection. “I can’t even remember what stones I bought and what I inherited,” Tulk told Forbes. “When I started collecting, it was from a sentimental, almost hoarding perspective, not from thinking this would be an investment.”

Tulk has maintained a colorful way to bankroll his Indiana Jones-like adventures. He’s a pop singer. Under the name Dion Todd, Tulk had hits in 2005 with “Maybe” and “Magic.” His “Rocketship State of Mind” peaked at No. 22 in 2017 on the Canadian Top 100. In 2019, “Be Alright” made it to No. 5 on the Billboard Top 50 Dance Club Songs chart.

As a gem hunter, Tulk says he doesn’t know how much money he spent amassing his collection. He does have a vivid memory of an open-air market in Chiang Rai, Thailand, and an old man who was selling dozens of gems. When Tulk told the old man he wanted to buy everything he had, the old man was happy. Tulk said he doesn’t remember what he paid, but he does recall that later, after he discovered what the stones may have been worth, he felt bad about the amount. So bad that when he returned to the region, he searched for the old man, to pay him more. Tulk said he never found him.

“There are many times I’ve acquired things where the seller didn’t really know what they were selling,” Tulk told Forbes, “and I didn’t find out what they actually were until many years later when I finally started to certify specimens.” Tulk said he requested the certifications not as a prelude to selling the collection, which he named for the mythical location of King Solomon’s mines, but to legitimize the collection to museums. Tulk showed Forbes letters from both Harvard’s Mineralogical and Geological Museum and the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History thanking him for donations.

The $3.2 billion appraisal “looks ridiculous.”

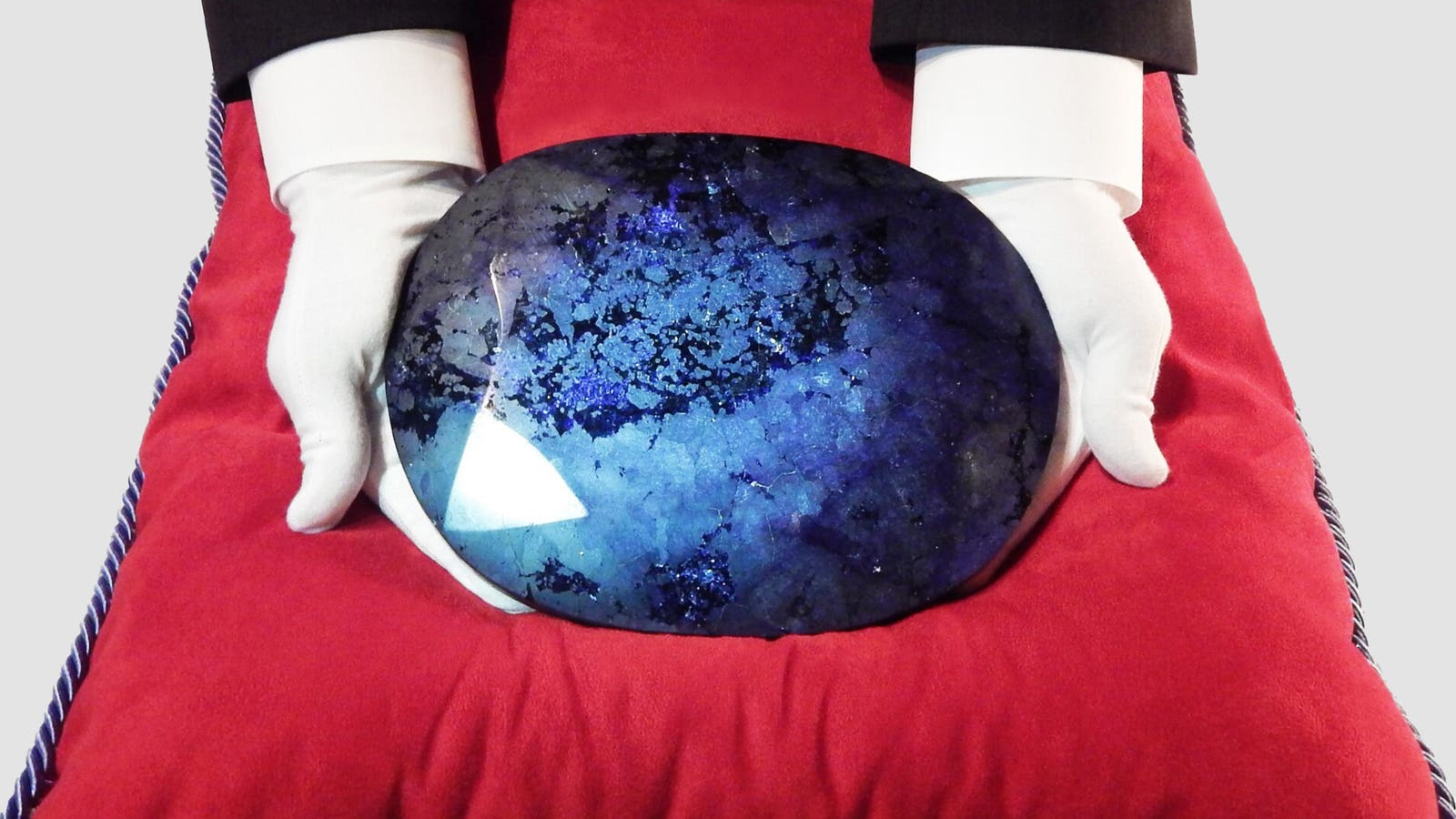

Starting in 2011, the Guinness Book of World Records designated nine gems in Tulk’s Ophir Collection as the biggest of their kind in the world. Included on the list was a faceted sapphire shaped like a round loaf of sourdough bread. To put the size in perspective, a cut blue sapphire called the Blue Belle of Asia, set in a diamond tassel pendant, sold in 2021 at Christie’s in Geneva for a record $17.7 million. That sapphire weighs 392.52 carats, or 2.8 ounces. Although size doesn’t always equate to value in the world of gemstones, it’s worth pointing out that the sourdough-sized sapphire in the Ophir Collection weighs 31,308 carats, or about 14 pounds.

Also part of the Ophir Collection was a mystery gemstone. Experts said they’d never seen anything like it before. They said it might be the only specimen of its kind in the world. They called it the Ophir Mystique.

Publicity around the Guinness records attracted potential buyers. Even if Tulk decided to sell, how was it possible to arrive at a price for a stone of a type no one had seen before?

An Ohio businessman named Brett Regal thought he had an answer.

Haggling Over Gems

In 2016, Regal offered Tulk $20 million for the Ophir Collection, according to legal papers, before sweetening the deal to $35 million. As part of the deal, Regal was to buy shares in a company Tulk owned a piece of. According to Tulk, the two executed a letter of intent to sell the gemstones contingent upon payment, but no formal sale agreement was ever signed and no money changed hands. “I think I’d know if $20 or $35 million hit my bank account,” Tulk told Forbes.By 2018, however, Regal allegedly began claiming to be the owner of the Ophir Collection. In a May 2020 complaint filed with a California court, Tulk alleged that Regal forged sale documents to take ownership. Regal denied this.

“I think I’d know if $20 or $35 million hit my bank account.”

Regal keeps a low profile. Attempts to reach him through his lawyers were unsuccessful. A clip search revealed no media coverage mentioning him. Public records show he’s affiliated with two companies. One of them, Migration Partners, is an LLC registered in Delaware. It has no website and the lawsuits where it’s named as a defendant offer no descriptions of what it does. It’s also unclear what line of business the other company, Trade Base Sales, is in. It lists as its headquarters a four-bedroom home, which Zillow values at $615,000, in a pleasant residential neighborhood in an eastern suburb of Cleveland called Beachwood, Ohio.

There’s a lawn, a maple tree out front and an attached garage. Hardly the sort of place for a treasure chest of pirate’s booty.

Having claimed ownership, Regal pledged the gemstones as collateral in a deal between his mystery firm, Migration Partners, and a company called Sterling Financial & Realty Group. Sterling is headed by Boca Raton, Florida-based financier Jeffrey Hackman, who has a colorful history of his own.

Precious Metals

Hackman, like Tulk, went into the family business. His father, Martin Hackman, was board chairman and Jeffrey was CEO when their publicly traded buyout firm, Met Capital, got into hot water with regulators in the early 1990s for not disclosing to investors, as securities rules require, that they were selling shares in the company. In this case, there were more than 300 transactions. In 1996, a permanent injunction was entered against Met Capital and Jeffrey Hackman. Hackman didn’t admit or deny the allegations and no civil penalties were levied. “That was 30 years ago,” Hackman told Forbes. “Life goes on.”

Sterling, another of Hackman’s firms, accepted the Ophir Collection as collateral in a 2017 deal with Regal’s Migration Partners. In the arrangement, Migration agreed to extract precious metals like gold and silver from 350,000 pounds of ore concentrate owned by Sterling. Regal’s company agreed to pay Hackman’s firm $1 million “from proceeds from the project” and $7.6 million in a promissory note. The gemstones secured that note.When Regal’s company didn’t pay, Hackman went to court in Florida and won the right to the collateral — the Ophir Collection. In the eyes of a Florida court, the gemstones that Tulk had spent years amassing now belonged to Jeffrey Hackman, a man Tulk had never heard of.

If the story ended there, it would be crazy enough. But there’s more.

Ocean Thermal

Around the time of the broken deal with Hackman, court documents show that Regal made a separate arrangement with a Philadelphia-based company called Ocean Thermal Energy, whose business, among other things, is using renewable energy to make seawater drinkable. Regal, representing his companies Migration Partners and Trade Base Sales, was in a consortium of investors that committed $42 million to Ocean Thermal, according to a breach-of-contract complaint that Ocean Thermal filed in 2018. In a Securities and Exchange Commission filing, Ocean Thermal said Regal was on the hook for $25.5 million. Regal’s failure to pay, and his creditors’ attempts to get from him anything of value they could, began a sprint to court to see who would win ownership of the Ophir Collection. Would it be Tulk, who’d traveled the world putting it together and said he’d never sold it? Would it be Regal, who claimed he had legal papers showing he was the owner? Or would it be Hackman’s Sterling Financial, which had won a Florida judgment saying it could take possession of the collection as compensation for the payment it was owed by Regal? Surprise: none of them. In July 2019, a California court granted Ocean Thermal permission to sell the collection to recoup the unpaid settlement money from Regal. Ocean Thermal didn’t respond to requests to talk.That was a funny outcome, but Hackman wasn’t laughing. Because a Florida court had already given his company, Sterling, the right to possess the gems, Hackman sued to assert his superior standing over the asset.

What followed was a prolonged legal tussle, this time in California. While that was happening, Regal found a buyer for the gems. Or thought he did.

Range Of Appraisals

In December 2019, Regal signed an agreement to sell the Ophir Collection to a Pretoria, South Africa-based company called Afristock Trading, which has no website and no paper trail that describes its business or its history.

It was the sale price, though, that knocked people over. It was $220 million — more than six times higher than what Regal had agreed to pay just a couple years earlier.

In the meantime, an appraiser named Lurisha Finger had assessed the value of the Ophir Collection. Finger, a graduate of the Gemological Institute of America and a GIA tutor, had ten years of experience “as an expert gemologist serving multiple retail jewelry stores and private jewelers” and was based in the San Diego area, according to a brochure for a panel on jewelry investment at a 2015 estate-planning conference.

Gemstone Gibberish

Take it with a grain of salt. These are the five most valuable gems in the Ophir Collection, according to a 2019 appraisal that’s drawn more laughs than nods from industry experts.

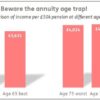

In February 2018, Finger appraised the Ophir Collection at $1.8 billion. She did another appraisal in May 2019 and came up with $3.2 billion. Nothing had changed about the collection in the intervening 15 months, but somehow its value had jumped 44%.

The $3.2 billion valuation “looks ridiculous,” Lisa Rosen, co-owner and CEO of the International Gem Society, told Forbes. “There’s value in having it in one collection, having the Guinness records, but the pool of buyers for this is very small and the current market values don’t support what’s here,” Rosen said.

Weird transactions have a magnetic pull. Social media eats them up, giving teetering businesses a boost.

Finger, contacted by Forbes, said she was unable to shed any light on her appraisals without the permission of the person who’d hired her. That was Regal, and he wasn’t talking.

There was something else fishy about Regal’s agreement with Afristock Trading, according to Hackman. He told Forbes it was amateurish and lacked basic details like deadlines for payment.

“It was a fake contract,” Hackman told Forbes. Afristock couldn’t be reached for comment.

Casting more shade on the deal was the person who was behind it. Payment was to be sent to London-based Genera Energy Ltd., a so-called buyer’s designee. Genera was headed by Benedict Moruthoane, sometimes spelled Moruthane. In 2011, Moruthoane had been sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison in the U.K. for defrauding investors under the pretense of investing in rare wines. Moruthoane didn’t respond to a request for comment.

In 2019, a court appointed a receiver to hold the gemstones and oversee its sale. The Ophir Collection, now stashed in a vault in California, was mired in a legal swamp that stretched across three states and involved two overseas companies. Its value remained a subject of debate.

Though Tulk insisted that he never sold the Ophir Collection, Hackman told Forbes that it remained a mystery whether that was true or not.“We never got to answer that question,” Hackman told Forbes. “There were documents that put Tulk into a box, notarized documents that said Brett [Regal] owned it. Nobody knows if Brett paid him or not.”Tulk maintained that he never received any money, but we may never get a definitive opinion from an independent source. The case in California was settled, but terms haven’t been made public. Both Hackman and Tulk told Forbes that according to the settlement they’d each receive a cut if and when there was a sale of the gemstones, but neither disclosed any other terms. Both Tulk and Hackman said they settled because the litigation could’ve gone on for years. They just needed to sell the stones.This past December, they seemed to have finally found a buyer. Sort of.

NFT Trades

Novo Integrated Sciences, a Bellevue, Washington-based company trading on the Nasdaq, with fiscal 2022 revenue of $11.7 million, was an unlikely bidder. The company runs health clinics, long-term care facilities and retirement homes across Canada. Novo CEO Robert Mattacchione told Forbes he understood the skepticism over his proposal. It’s not every day a healthcare company buys sapphires. But his explanation wasn’t all that helpful either.

“We’re not traditional when we’re looking at financing options,” Mattacchione told Forbes. “You’ve got to think outside the box to raise capital right now. This isn’t a pie-in-the-sky play to boost our balance sheet. It’s a unique situation to avoid the normal dilutive financing arrangements and it only gets executed if we complete the back-end monetization piece first.”

In 2011, Moruthoane was sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison for defrauding investors under the pretense of investing in rare wines.

The deal he proposed was as convoluted as his explanation for it. Mattacchione said he’d somehow buy a Jacksonville, Florida-based NFT company called SwagCheck for $90 million — at the time, three times more than the value of Novo’s outstanding stock — and SwagCheck would use $60 million of that to purchase the Ophir Collection. The idea was that SwagCheck would then mint non-fungible tokens of the gemstones while Novo would figure out a way to monetize them.

Forget that 95% of NFTs are worthless. Disregard the fact that a healthcare company seemed determined to use a collection of difficult-to-value and hard-to-sell gemstones to raise money. But don’t ask Mattacchione to elucidate further. That might only add to the confusion.

The explanation could simply be desperation. Novo stock, accounting for reverse splits, hit an all-time high of around $6,000 in 2006. For the last year or so, it’s traded below $5. Owning assets with debatable value can be a shrewd play for such a company. It’s been done before. There was the oil company that told investors it had billions of barrels in reserves. There was the movie-theater chain that bought gold. Weird transactions have a magnetic pull. Social media eats them up, giving teetering businesses a boost.

In August, Novo issued a statement about ongoing negotiations, and in September, on social media, Mattacchione said there’s been “significant headway and continued energy by all parties” to get a deal done.

Both Tulk and Hackman insisted, however, that talks with Novo have been dead for months. It might be the one thing the two men agree on.

“I haven’t heard Novo’s name since December,” Hackman told Forbes. “I don’t think they ever had the financing to begin with. If the receiver knows about it, then I’d know about it. I haven’t heard anything and the deadline was at the end of last year.”

The court-appointed receiver, Blake Alsbrook, declined to comment.

“All these people are looking to use an asset they don’t own to raise money off of it,” Tulk told Forbes.

The next chapter in the story, whatever it is, may just be a prelude to even more convolutions. Tulk told Forbes that the Ophir Collection isn’t the only one he’s put together. He’s got another collection of precious stones.

So far, he’s the only one who claims to own it. But that could change.

MORE FROM FORBES

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.