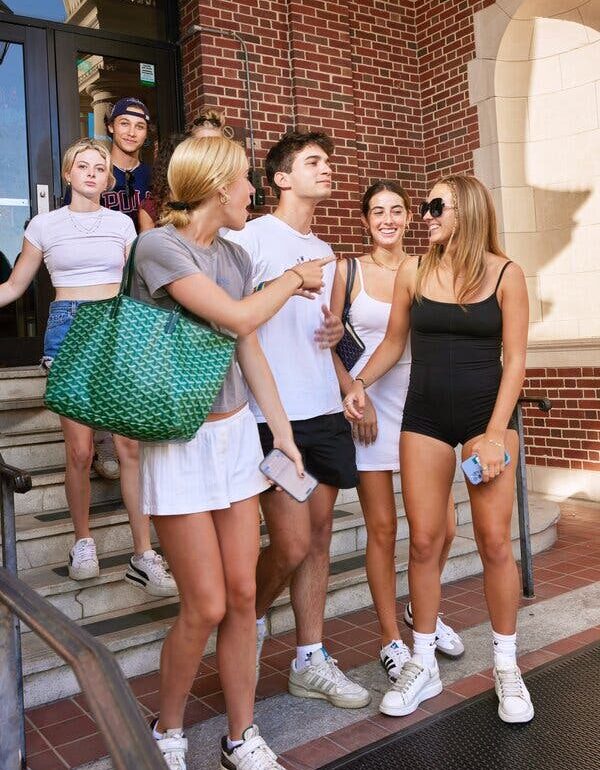

In the spring of 2021, about 2,000 students on the campus of Tulane University in New Orleans received an email they were expecting. They had filled out an elaborate survey provided by Marriage Pact, a matchmaking service popular on many campuses, and the day had come for each of them to be given the name of a fellow student who might be a long-term romantic partner. When the results came in, however, about 900 straight women who participated were surprised by what the email offered: a friend match instead of a love interest. The survey was a lark, something most Tulane students saw as an icebreaker more than an important service. But the results pointed to a phenomenon at the school — and at many other schools — that has only grown more pronounced since then, one that affects much more than just students’ social lives: Women now outnumber men on campus, by a wide margin.

Listen to This Article

Last year’s freshman class at Tulane was nearly two-thirds female. Tulane’s numbers are startling, but the school is not a radical outlier: There are close to three women for every two men in college in this country. (The way schools report gender may not yet reflect many students’ nonbinary understanding of it, but the overall trend is clear.) Last year, women edged out men in the freshman classes of every Ivy League school save Dartmouth, and the gender ratio is significantly skewed at many state schools. (The rising sophomore class at the University of Vermont is 67 percent female; the University of Alabama is 56 percent female.) Most small liberal-arts colleges are close to 60 percent female, and the discrepancy is even more pronounced at community colleges and historically Black colleges and universities. Colleges with powerhouse football teams or the word “technology” in their name, or elite schools known for engineering, like Carnegie Mellon, tend to be closer to parity or even have more men, but it is safe to say that a college graduate under 60 today is more likely to be female than male — especially since men also drop out of college more often than women.

The gender gap in educational achievement starts early: Girls are already significantly outperforming boys on reading and writing tests by the time they are in fourth grade, an advantage that is often attributed to differences in brain development, despite inconsistent findings in neuroscientific research to support that explanation. In high school, girls volunteer more on average, all the while getting higher grades, including in STEM subjects. By the time they graduate, they make up two-thirds of the top 10 percent of their class. Although men have historically performed better on standardized college-admissions tests, women have inched past them on the A.C.T. and almost closed the gap on the SAT.

That young women are better prepared to excel in college helps explain why more of them apply in the first place. But economic calculations are also affecting young men’s decisions about whether to enroll: Wages are higher for young people than in the past, which increases the immediate opportunity cost of paying tuition. The trade-off is especially relevant for young men, who tend to earn higher wages without a college degree than their female counterparts — they might find jobs in construction or technology, which pay significantly more than the ones young women often land in elder care or cosmetology. Conservatives have also steadily been devaluing higher education in ways that might be more salient for men; the critique that liberal-arts colleges are pushing “gender ideology” on students positions those institutions as threatening to traditional conceptions of masculinity.

Men’s relative lack of engagement in higher education is both a symptom and a cause of a greater problem of “male drift,” as it has been characterized by Richard Reeves, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. Reeves points to rising rates of suicide among young men as a distressing signal of a vicious cycle underway: Men without college degrees tend to be underemployed, and underemployed men are less likely to marry and benefit from the grounding influence of raising children. “These guys are genuinely lost,” says Reeves, who recently founded a think tank, the American Institute for Boys and Men, to focus attention on the issue. The gender gap in higher education has been a concern in education circles for decades, but as is true of so many trends, the pandemic seems to have only exacerbated the problem: Male enrollment plummeted more quickly than female enrollment and has not bounced back to the same degree.

As a result, many schools are fighting hard to close the gender gap — not only for the students’ benefit but also for their own. It’s a longstanding fear among enrollment officers that if the gender ratio becomes too extreme at a given school, students of all genders will start to lose interest in attending (an idea that persists even if none of the admissions experts I spoke to could point to research about college enrollment supporting it). “Gender parity is something that’s an institutional priority for most private colleges and universities in the United States,” says Sara Harberson, a former dean of admissions and financial aid at Franklin & Marshall and the founder of Application Nation, an online college-counseling community. “Whether it’s fair or not, colleges with gender parity or close to gender parity have been viewed as the most desirable.”

Some schools are trying to attract male applicants by improving their sports programs; others invest more heavily in buying boys’ email addresses or give incentives to boys that they do not offer to girls — such as free stickers or baseball caps — for filling out information on the school website. Marketing materials are sometimes designed to speak specifically to young men. Heath Einstein, dean of admission of Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, recalls fondly a pamphlet known internally as the “bro-chure,” which featured shots of the football team, a rock climber and a male student shoving cake in his mouth. But the easiest way for many competitive schools to fix their gender ratios lies in the selection process, at which point admissions officers often informally privilege male applicants, a tendency that critics say amounts to affirmative action for men.

The number of women seeking higher degrees started soaring in the 1960s and ’70s, and by the early ’80s, more women were attending college than men. The trend continued upward, so much so that by 1999 some universities had admissions policies that explicitly favored men. At the University of Georgia, admissions officers automatically gave male candidates an additional 0.25 points (out of a possible score of 8.15). In doing so, the school managed to maintain a ratio of 45 percent men to 55 percent women. That year, three white women filed suit against the Georgia university system’s Board of Regents, claiming that the school had discriminated against them on the basis of gender and race. (The university gave nonwhite applicants an extra 0.50 points.) The young women’s lawyers argued that the extra points for men violated both the equal-protection clause and Title IX, which guarantees equal educational opportunities for men and women. The district court overseeing the case ruled the policies unlawful, and although the school appealed its race-based policy, it dropped its policy on gender. Other state schools with similar policies followed suit.

But Title IX does not prohibit gender-based affirmative action in admissions at all schools. In 1972, when the details of Title IX were still under discussion, the presidents of some of the country’s most elite private universities persuaded legislators to exempt their admissions policies from the law. In a 2021 Duke Law Review article, Katie Lew, then a law student, explains that they worried that high numbers of women, right away, might render the school unrecognizable to the male alumni whose donations were so crucial. Such high female enrollment would even make fund-raising harder, they argued — how was the development team supposed to track down women who changed their names upon marriage? Threats to academic integrity were conjured: The president of Princeton, in a letter to the panel working on the legislation, expressed the fear that the school might be forced to “dilute” the academic offerings made to men if they had to build separate departments to accommodate what he assumed to be women’s interests.

That Title IX exemption still stands, allowing private colleges and universities to privilege men during the admissions process. Marie Bigham, the executive director of ACCEPT, a group that works to improve equity in college admissions, said that until the pandemic, when many schools stopped requiring standardized tests, she considered the boost for being male to be about “equal to an extra 100 points on their SATs.” Angel B. Pérez, who ran enrollment at Trinity College until 2020, told me that it wasn’t unusual for the initial selection rounds there to skew heavily in favor of women. “There were some years when it was in the extremes, and I’d say, ‘We just can’t do this,’” says Pérez, who is now chief executive of the National Association for College Admission Counseling. “I can’t come up with a class of 20 percent men — that’s just not good for the campus.” At that point, he said, the team would go back and seek more men to balance the class.

“There was definitely a thumb on the scale to get boys,” says Sourav Guha, who was assistant dean of admissions at Wesleyan University from 2001 to 2004. “We were just a little more forgiving and lenient when they were boys than when they were girls. You’d be like, ‘I’m kind of on the fence about this one, but — we need boys.’” Jason England, a professor of English at Carnegie Mellon who worked in admissions at Wesleyan from 2004 to 2006, says the process sometimes pained him, especially when he saw an outstanding young woman from a disadvantaged background losing out to a young man who came from privilege. “The understanding is that if we’re going to have close to a 50-50 split, then we need to admit men, and women are going to suffer,” he says of that time.

For the sake of a well-rounded student body, Wesleyan leadership still believes in making choices that yield an even ratio, even if it sometimes means passing over an exceptionally qualified girl in favor of a boy whose application is not quite as strong. “If you had all these people who were really superb but they were all shortstops, you wouldn’t take them, or all violin players,” says Michael Roth, Wesleyan’s president, “because you need other people in the orchestra.”

Even after the lawsuit at the University of Georgia, some state schools persisted in privileging male applicants, at least informally. “We, and every other college these days, give a male applicant a second look,” Louis Hirsh, then the dean of admissions at the University of Delaware, told the reporter Peg Tyre for her 2008 book “The Trouble With Boys.” It wasn’t that they were taking demonstrably worse male candidates over female ones, he clarified, but they would look harder for reasons to accept the male ones in the name of a better ratio.

The following year, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights began an investigation into gender discrimination in admissions at 19 colleges and universities in the mid-Atlantic region, but the inquiry was dropped in 2011 on the grounds that the statistics the panel received were not sufficient for accurate analysis. Some commentators in the press theorized that Democrats on the panel might have been wary of opening a larger conversation about race and affirmative action. In her book “The End of Men,” Hanna Rosin suggests that they were uncomfortable with the prospect of publicizing that men, rather than women, were the ones in need of support and help.

Even now that the Supreme Court has struck down race-based affirmative action, colleges are very likely not panicking about their efforts to maintain some control over their gender ratios: The Supreme Court gives parties more leeway to discriminate on the basis of gender than it does on the basis of race. Nonetheless, Einstein says he has heard representatives of the most elite institutions discuss the possibility of stripping information about gender from the versions of applications that admissions officers read. Admissions officers could not help discerning the sex of the applicant in most instances, but that small, formal change of policy might still give litigants seeking an ideal testing ground a reason to target some other elite institution. “They’re doing everything in their power,” Einstein says, “not to be at the epicenter of a lawsuit.”

For self-protective reasons, and out of genuine concern about equity, admissions officers would prefer to increase the number of men who are applying to their colleges, rather than favoring male applicants in the final round of selection. “Think about the front end of the equation when you’re trying to get people interested in your institution,” Madeleine Rhyneer, the dean of enrollment management at EAB, a higher-education consulting firm, told me she advises her clients.

It’s common wisdom that athletes have an advantage over nonathletes in elite admissions because schools need to fill teams, but at many schools it’s the other way around — the school needs the teams in order to inspire more men to apply in the first place. “As schools get more desperate to recruit male students, one of the avenues for attracting them is an emphasis on recruiting for traditionally male sports in particular,” says Guha, now executive director of the Consortium on High Achievement and Success, a nonprofit at Trinity College that works to help both students and staff members of color succeed on campuses. Colleges believe that varsity sports attract male students, which is one reason that, even as research on the health risks of football grows, some 73 schools added football teams over the past decade or so. Football teams can have rosters of more than 100 players, and they also pull in other young men who are simply attracted to a school that has tailgate parties and football games.

Adding a football team does bump up male enrollment for the first year, but the effect fades after about three years, research has found. And not every small liberal-arts school can afford to add a football team. For that reason, some schools are turning to sports such as men’s rugby and volleyball that don’t have the high costs associated with experienced football coaches, stadiums and large rosters.

Schools’ efforts to attract men can create a strange dynamic: The scarcer men are, the more they end up driving a school’s priorities. “Unlike a large Division I school, where even a large football team is a tiny fraction of the study body, at a relatively small school, if you have 2,000 students, and 1,000 are men, and 100 of them are playing football, suddenly 10 percent of the male population is a football player,” Guha says. “You add that up with additional large teams — lacrosse, ice hockey — and a larger proportion of the male population participates in these sports, and they come with a particular identity and culture of what it means to be a man. And I think it does disproportionately shape the experience on campus.” At Lewis & Clark, a progressive school in Portland, Ore., that typically skews very heavily female, fully 21 percent of the men in the freshman class this fall are on the football team.

Sports are an imperfect solution to address the urgent problem of male enrollment, argues Laurie Essig, a professor of gender, sexuality and feminist studies at Middlebury. “Men and boys have been disadvantaged by patriarchy, too,” she says. “We tell boys, ‘Sports is all that matters.’” Essig points out that when schools try to attract male students with the promise of sports, they are only perpetuating the problem they are trying to solve, which is an emphasis on sports at the expense of full academic engagement. It troubles her that even at an elite school like Middlebury, athletes regularly miss class for games or say they don’t have time to do even minimal amounts of homework because they are so busy working out and traveling to compete.

During his time at Wesleyan, Guha told me, he noticed that female athletes were still expected to have stellar grades and other interesting activities. “Whereas for the boys, you saw it very clearly — their sport was their identity and their value as a young person in society,” he says. “It was all based on athletic excellence, and a lot of other things fell away. And that seemed to be OK with everyone.” A 2010 study of 84 Division III colleges and universities found that recruited male athletes had lower G.P.A.s than nonrecruited male athletes, which was only marginally true of recruited female athletes.

Because schools have to be careful not to trigger a Title IX violation, one the most popular new varsity sports on college campuses is ostensibly gender neutral: varsity e-sports. E-sports teams compete against other schools in games like Super Smash Bros and Valorant, a “tactical hero shooter” game, events that also have the benefit of being inexpensive. “Many schools recommission old rooms that aren’t seeing much use,” the author of a blog post on gamedesign.org wrote in an article charting the rise of those programs. “They gut it, spruce it up and fill it with gaming gear. Boom, there’s your varsity e-sports training facility.” About 500 colleges and universities now have e-sports teams, according to the National Association of Collegiate Esports (NACE), and the consulting firm EAB says it has fielded around a dozen requests from schools interested in introducing one. This year’s college tour at the University of Delaware (whose rising sophomore class is 54 percent female) features a visit to the high-tech e-sports arena at its student center, which campus guides present with evident pride. Nationwide, close to $25 million was given away in varsity e-sports scholarships in 2022, and that number is expected to grow, with technically gender-neutral scholarship money effectively being used to benefit and attract mostly men. According to NACE, only 8 percent of college e-sports players are women.

As all-women colleges have long advertised, women benefit in many ways from being in the majority on campuses, where they may feel freer to explore academic subjects that are typically dominated by men. Tulane, for example, can boast that the makeup of its computer-science classes ranges from 35 to 50 percent female, depending on the year, while computer-science programs at peer schools tend to max out at around 25 percent. The student newspaper and magazines are also dominated by women.

Tulane has not actively been trying to shift its gender ratio, Jeff Schiffman, a higher-education consultant who worked in recruiting at Tulane for 16 years, told me. The school has invested in its football team, but it has no men’s soccer or lacrosse team. “The gender balance was never part of the planning narrative,” he says. “No one ever said, ‘We have a major problem.’ The faculty thought students were performing well, and there was no need to make major shifts.” But Brian Taylor, a managing partner at the college-advising business Ivy Coach, believes, based on what his team sees, that Tulane accepts more boys than girls for whom the college would be considered a “reach.” “Tulane is no Seneca Falls,” he says. “They’re playing the hand they’ve been dealt.” Taylor says that he’s more likely to encourage a young man with unremarkable grades to apply than a female applicant with a similar transcript. (A representative of Tulane told me that the school is “an equal-opportunity educator”: “The notion that Tulane has lower admission or academic standards for its male applicants versus its female applicants is completely false and without merit.”)

That there was a difference in the strength of male students relative to female ones seemed obvious enough to Mercedes Ohlen, a communications and anthropology major who also edited a lifestyle magazine on campus. She says that she and her friends frequently discussed the fact that their male classmates didn’t seem to be working as hard, which they found frustrating. “Some of these boys were just taking these classes to kind of get through it and get their degree and leave,” says Ohlen, who graduated this spring. Taylor Spill, a senior, says Ohlen’s take on male students at Tulane was so commonly held that she felt bad for the high-performing male students. “It’s almost like it’s reverse sexism,” she says. “Here at Tulane, I feel like the women kind of underestimate the men. Sometimes they’re right. Sometimes they’re not.”

Even as young women outnumber men on college campuses, and increasingly walk away with academic awards, men, some have argued, exert an outsize influence on campus social lives. In the 2015 book “Date-onomics,” the business reporter Jon Birger builds the case that hookup culture has become the norm on almost all college campuses, largely because the gender ratio is so skewed. In a world in which straight men are scarce, he maintains, they control the terms of social life. That argument may seem somewhat dated given that so many students now have a wider and more fluid understanding of gender and sexual orientation.

Even so, several women at Tulane expressed to me their sense that the gender ratio left them with fewer options, in sheer numbers and in the kinds of relationships available to them. Emma Roberts, who graduated from Tulane in the spring, told me she discussed the problem in her gender-studies class. “I think everyone’s consensus we came to was that it’s pretty disgusting trying to date,” she says. “Because the reality is you’re not likely going to find someone that wants to date you.”

Women I spoke to at the University of Vermont agreed that high numbers of female students did not necessarily make for a feminist haven. “It shocks me how many women we can have here and still have a horrible toxic male culture,” said one woman, a junior who didn’t want to be named because she was candidly discussing her sex life. On the evening I met her in early July at an outdoor cafe near campus, she and two friends spoke frankly about their frustrations with dating in college. They characterized the straight men at their school as “picky” and “cocky.” All three felt they had settled too often — that by the time they left school, they were less confident about what they had the right to ask for in a relationship. The young women were older and wiser than when they started, ready to head into the world with the economic advantages that are associated with a bachelor’s degree. But for all their achievements, they also left feeling — to use a word they all agreed on — “humbled.”

In order to help more men enroll in college, some researchers have insisted that changes need to start as early as kindergarten. Already many upper-middle-class families hold their sons back a year before enrolling them in school. That’s an option that could be adopted for boys more broadly across all socioeconomic groups, Reeves, the Brookings Institution researcher, has proposed, although he also acknowledges that the burden of paying for an additional year of child care is substantial.

Clearly, society suffers when any large group of the population is cut off, for whatever reason, from the most effective engine of upward mobility, which is why leaders in higher education are thinking innovatively and aggressively about how to recruit more male students, especially in Black and Latino populations, whose college enrollments are lowest. “There’s a reason they passed the G.I. Bill,” says Marjorie Hass, president of the Council of Independent Colleges. “It’s typically not good for society when young men feel they don’t have a future.”

But the issue of admissions equity raises different questions at elite colleges, where a clear gender paradox has emerged: The more women succeed, as a group, in high school, the harder it is for them to gain access to some of the schools that forge the most direct path to positions of real power. At Brown, for example, almost 7 percent of men who apply are admitted, compared with 4 percent of women. Jayson Weingarten, who worked as an assistant director of admission at the University of Pennsylvania for six years and is now a senior admissions consultant at Ivy Coach, estimates that at most highly selective colleges, the ratio of women to men would be closer to 60-40 if gender weren’t a factor, rather than the current norm, which is close to 50-50.

Schools’ efforts to attract men can create a strange feedback loop: The scarcer men are, the more they end up driving a school’s priorities.

In defense of class “shaping,” Michael Roth, Wesleyan’s president, suggested to me that even numbers of men and women make for a better learning environment — one that prepares young people for the professional world. “You will probably work and live in a context where there are men and women and nonbinary people,” he says, addressing an imaginary student. “And I think when schools become unintentionally focused on one gender, they have a diminished capacity to prepare people for the world beyond graduation.”

But the world beyond graduation Roth invokes is one in which women are still struggling to gain access to the highest echelons of power. They remain underrepresented in C suites, on boards, in Congress, on the Supreme Court and in the White House. If anything, by the logic of affirmative action that schools like Wesleyan embraced for years, young women might still be considered the more worthy beneficiaries. While recognizing that women still haven’t reached parity at the highest levels, Reeves argues that ensuring a strong male presence on elite campuses has value that extends beyond the diversity of the learning environment. “You don’t want to feel like there’s something incompatible between masculinity and educational excellence,” says Reeves, who worries that if college comes to be understood as a feminine pursuit, that notion would be hard to reverse.

How to grant women their due while addressing the concerns that Roth and Reeves raise is a complicated question at any school, but offering more transparency would at least allow for a more informed debate. Emily Martin, the vice president for education and workplace justice at the National Women’s Law Center, believes that if people better understood the advantages given to men, the national conversation about affirmative action might look very different. “The status quo of widespread affirmative action for men sits uneasily with the deep sense of grievance from those we hear speaking on behalf of white men,” she told me. “In the higher-education context, that ranges from attacks on race-based affirmative action to broader attacks on diversity, equity and inclusion, to attacks on gender-studies programs.” At the very least, Martin says, we should know when there’s a thumb on the scale, and for whom.

Maggie Shannon is a photographer based in Los Angeles. Her work focuses on stories of smaller communities and social rituals.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.