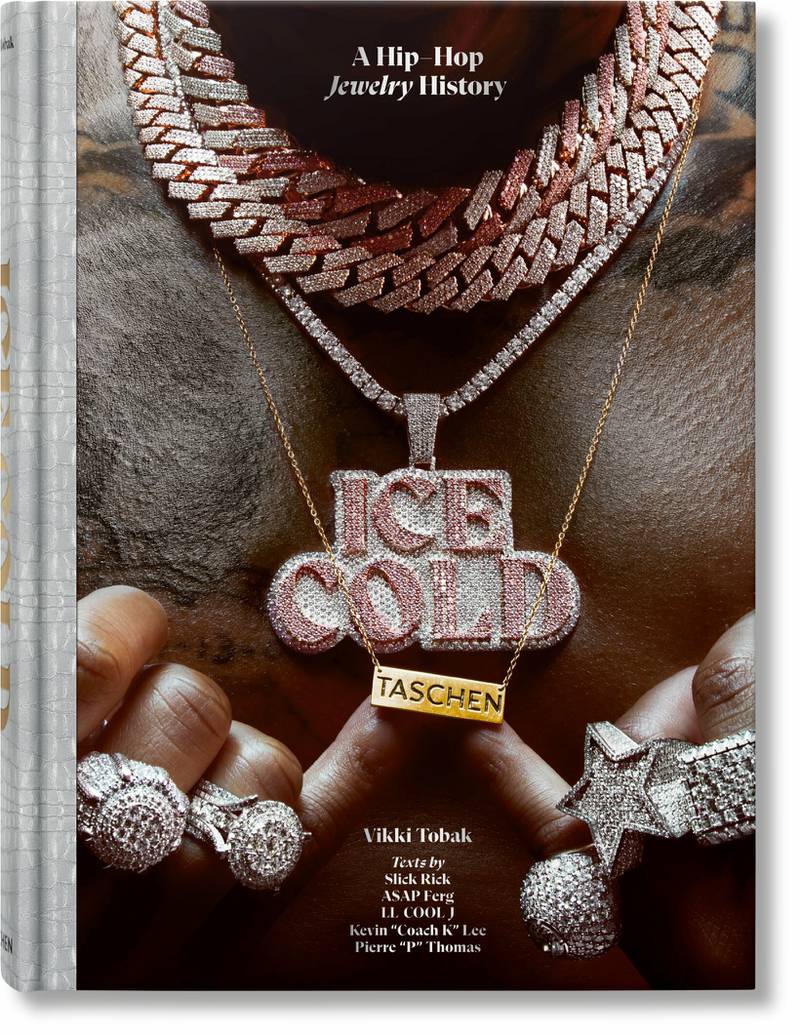

From the simple gold chains sported by the pioneering rappers of the 1970s to the bold, customised creations of the 1990s and the bejewelled “sky’s-the-limit” pieces of the 2000s, the worlds of hip-hop and jewellery have always been immutably linked.

Hip-hop’s decades-long love affair with jewellery has also birthed dookie ropes, nameplate necklaces, four-finger rings and bejewelled grills.

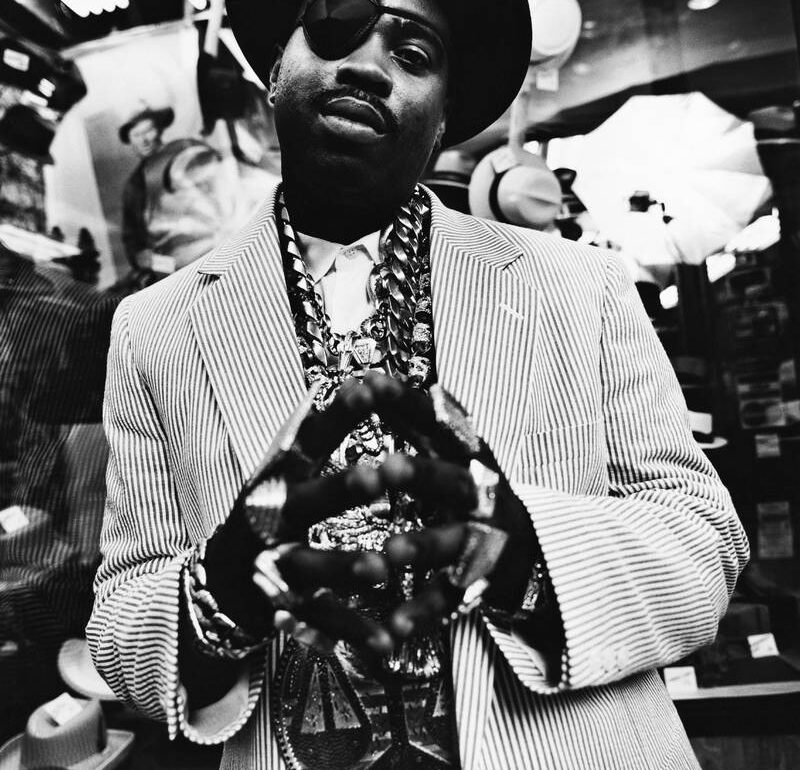

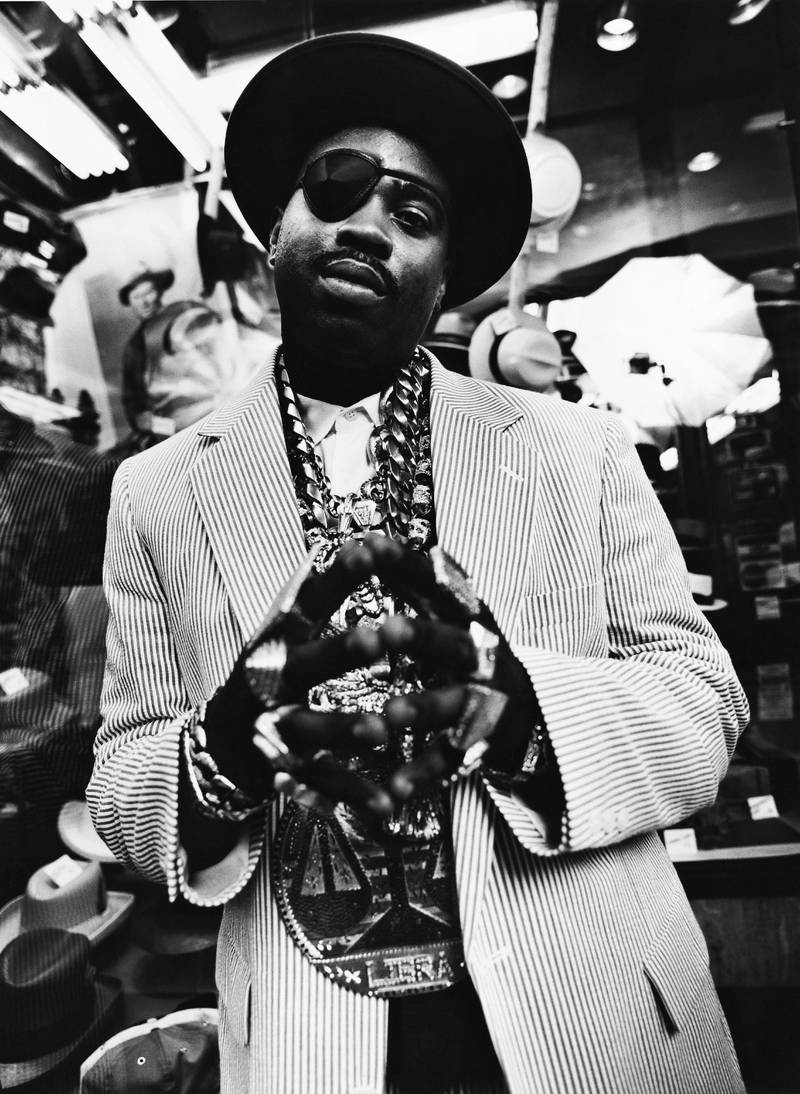

“I’ve been telling stories with my attire and adornments for as long as I’ve been telling them with beats and rhymes,” rapper Slick Rick writes in the foreword to Vikki Tobak’s new book, Ice Cold: A Hip-Hop Jewelry History, touching on how clothing and accessories are as integral to hip-hop culture as the music itself.

Firmly embedded in the aesthetic, these adornments became physical manifestations of status, upward mobility and changed circumstances despite the odds. They told stories of ancestry, the self and the struggle, and acted as markers of allegiance and aspiration. They were much more than mere trinkets.

“My jewels are my superhero suits, an extension of my beautiful brown skin,” Slick Rick continues. “It’s a gift from ancestors who sat on thrones and reigned with rings and rocks the size of ice cubes.”

He writes about coming across a huge Libra pendant in the window of a jewellery store on New York’s Canal Street in the mid-1980s. He continued coveting the piece (even though he is a Capricorn) and with “time, patience, hard work and success” was able to walk into that shop nine months later and pay for it in cash. “Jewellery speaks silently but screams personality,” he says. “Displaying our opulence affirms the traditions and wealth of our culture.”

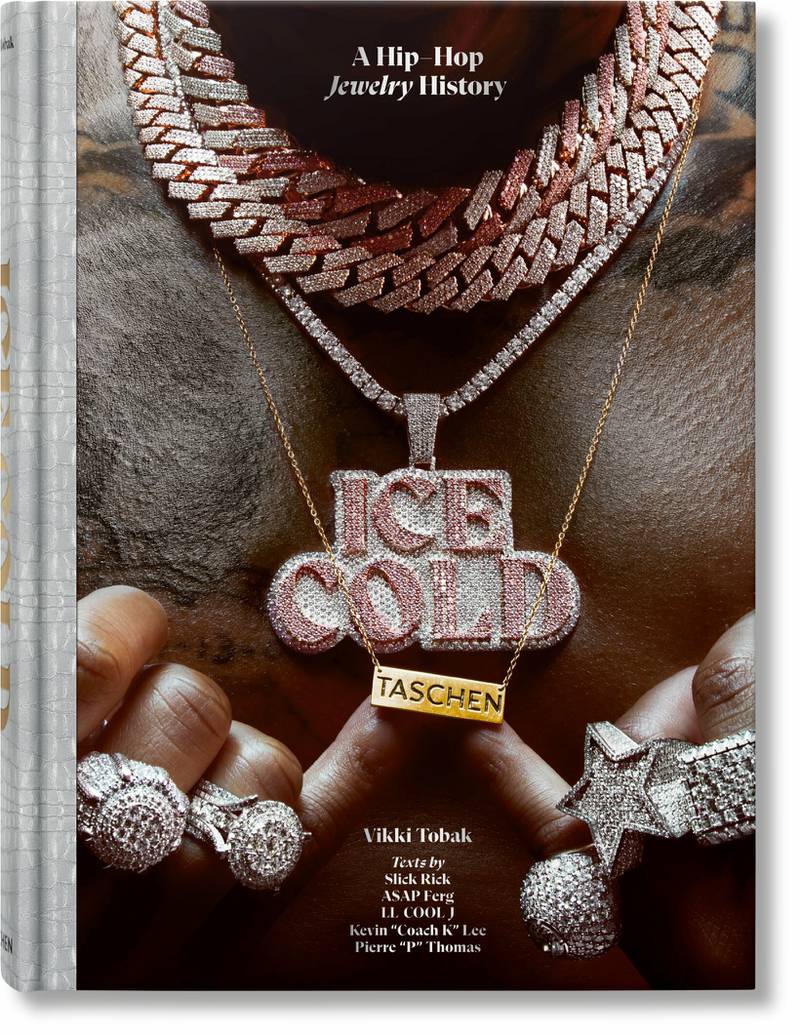

Tobak has spent the past 25 years writing about hip-hop, having started her career working for a music label before serving as Jay-Z’s first publicist and then moving into journalism. Her first book, Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop, featured rare outtakes from more than 100 era-defining photoshoots, alongside interviews and essays from industry legends.

“When I was doing Contact High, which was a photographic history, you of course notice all the little sartorial details – the sneakers, obviously, and the clothing, by Dapper Dan and other very specific designers. All of that is very well documented. But the jewellery was there hiding in plain sight, at least in terms of a story,” says Tobak, who launched her latest work in Dubai during Sole Dxb last year.

“It was a natural time to tell that story,” she told The National. “Next year is the 50th anniversary of hip-hop and when you think about what the jewellery started from in the late 1970s – very humble, little gold chains and hoop earrings for women – to what it has become now, in terms of its stature in pop culture and the world of luxury. It’s now a pop culture phenomenon, it’s now a luxury phenomenon and it’s a great come-up story.”

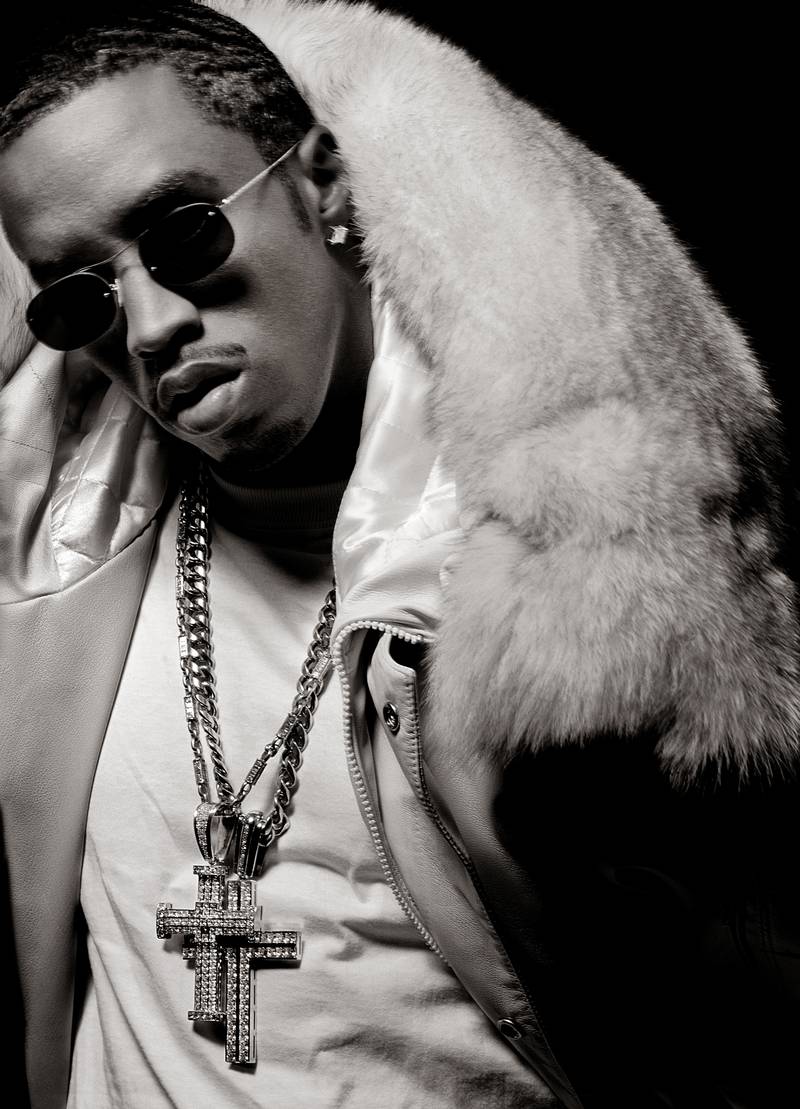

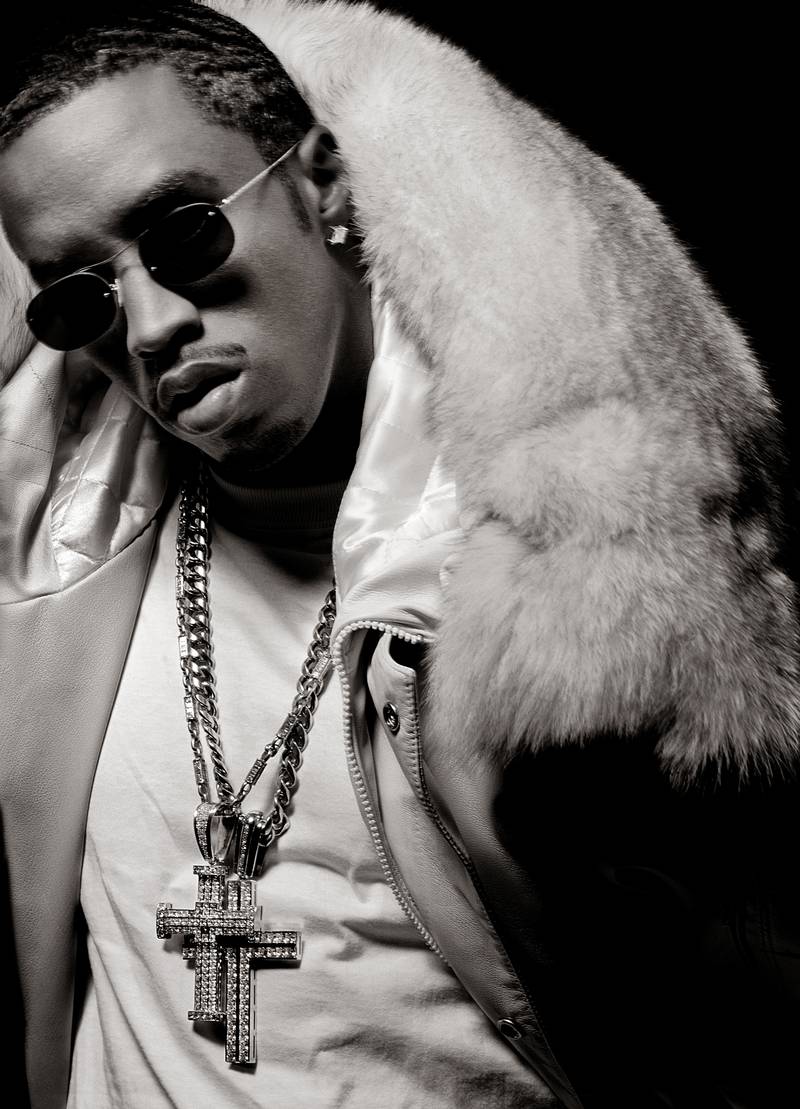

In 1980, Kurtis Blow donned six layered gold chains for the cover of his self-titled debut album, officially solidifying the link between hip-hop and jewellery. It kick-started an era of increasingly distinctive designs – remixed Mercedes-Benz and Rolls-Royce logos descending from giant gold chains; religious motifs, including crosses, angels and Jesus heads, reshaped into oversized medallions; memory pendants immortalising lost loved ones; and deeply personal pieces chronicling names, neighbourhoods, astrological signs, birth dates or crew affiliations.

“Certain gold link styles became instant street classics,” Tobak writes. These included the figaro chain, an alternating pattern of oval and circular links; herringbone chains, with their tightly woven, seamless designs; and, most famously, the Cuban link, consisting of thick circular or oval-shaped gold pieces.

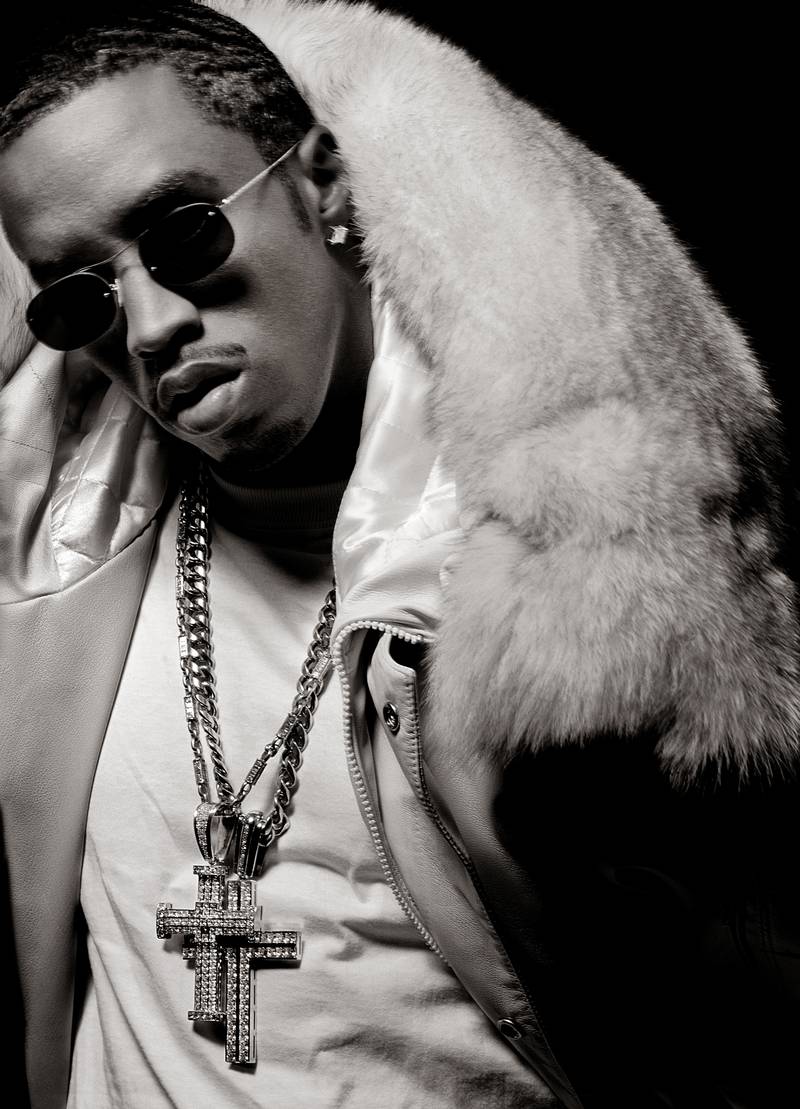

In the 1990s, hip-hop moved out of the clubs and into the boardroom, birthing business moguls such as Jay-Z and Sean Diddy Combs. Jewellery became bigger and bolder, now laden with diamonds, gemstones and platinum.

In the mid-1990s, the original New York hip-hop jeweller Tito Caicedo created Notorious BIG’s first Jesus piece, since dubbed “the Hope diamond of hip-hop”. The Jesus motif has been remixed in myriad ways, by almost every rapper in existence, and remains a constant symbol of faith and success.

Chains emerged that spelled out artists’ allegiance and loyalty to their chosen record labels – perhaps most famously in the case of Death Row Records chief executive “Suge” Knight and rapper Tupac Shakur’s matching pendants, depicting the label’s logo in diamonds – an inmate strapped to the electric chair.

In the 2000s, as the commercialisation, influence and wealth associated with hip-hop have continued to expand, the stakes have grown ever higher. Tobak points to Kanye West’s gigantic Horus medallion and chain, worth about $300,000; Jay-Z’s 5-kg Cuban gold chain, priced at about $200,000; and Lil Uzi Vert’s Marilyn Manson chain, worth $220,000.

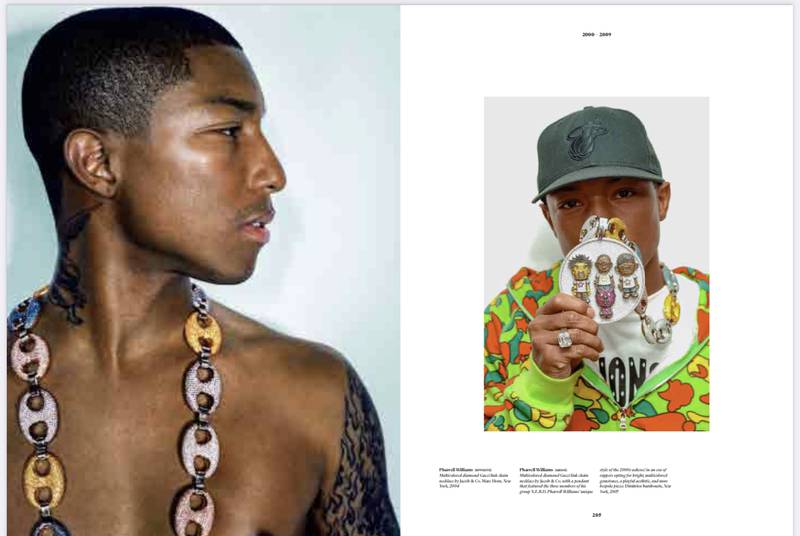

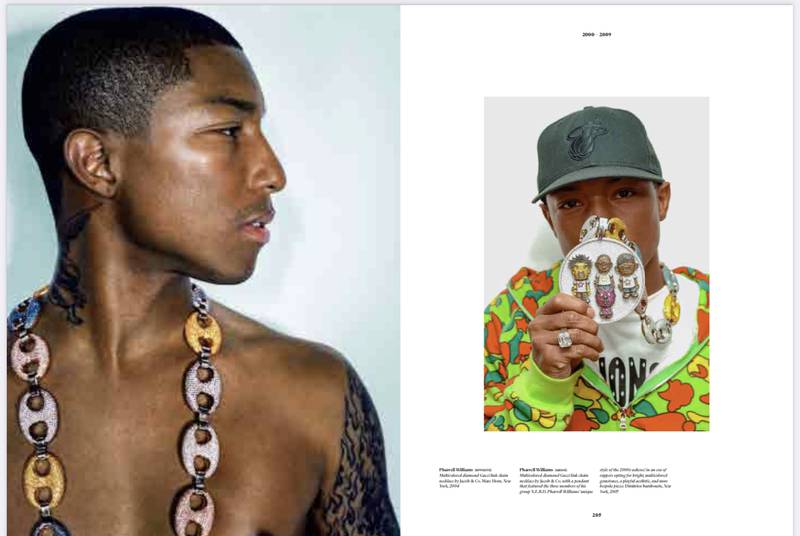

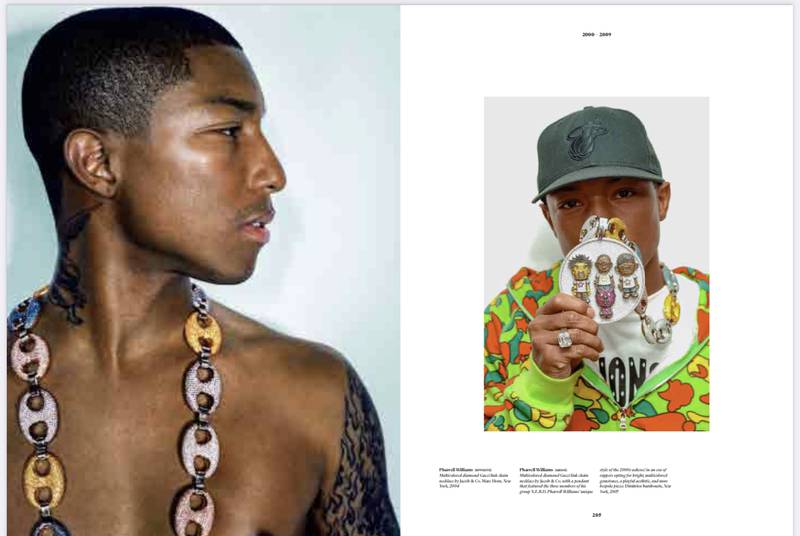

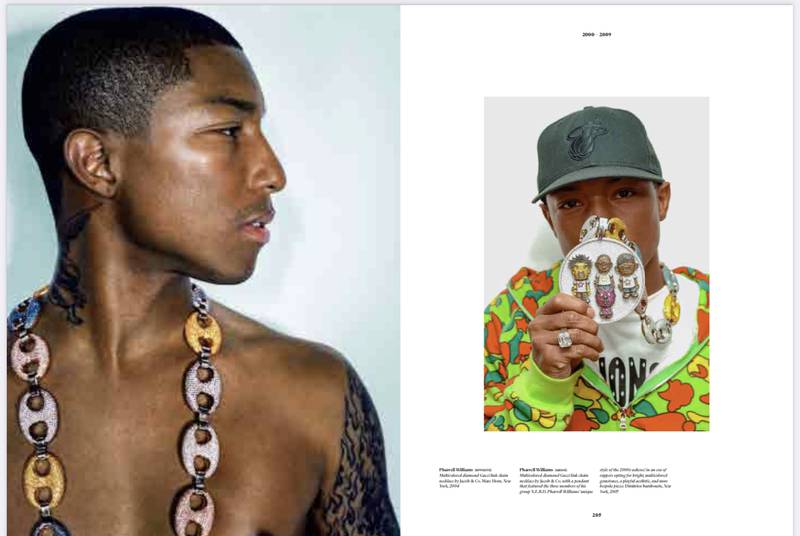

Artists such as Pharrell Williams, Tyler and Cardi B have become bona fide collectors, while A$AP Rocky arguably leads the way in terms of experimentation and subversion. From the beginning, customisation has been key. “The jewellers that worked with hip-hop, just like the fashion designers that worked with hip-hop, had to have a certain understanding of the hustle, the spirit of it,” says Tobak. “Hip-hop has this great tradition of customisation and remixing, of having things that nobody else has. The street was the runway and you wanted to stand out.

“So, even if they could afford it, they couldn’t just walk into Tiffany & Co, because they didn’t want the same things everybody else had. They wanted something that spelled out their name, or they wanted a mix of two links, like a Gucci link and a Cuban link.”

Dedicated hip-hop jewellers include Tito of Manny’s and Avianne & Co, as well as more contemporary artisans such as Greg Yuna, Alex Moss and Eliantte, plus Icebox Jewelers and Iceman Nick. “When the luxury brands fall short and don’t serve us, we create our own luxury,” Rick says.

One of hip-hop’s greatest unsung collaborators is the Uzbek-American designer Jacob Arabo. Having emigrated to the US with his family as a teenager in the 1980s, Arabo was working in New York’s diamond district, and began designing custom made pieces under the name Diamond Quasar. A commission for the Brooklyn rapper Notorious BIG earned Arabo the nickname “Jacob the Jeweller”, and soon other rappers were requesting one-off gold and diamond pieces.

By 1986, Arabo launched Jacob & Co to cater to the likes of Combs, Williams and Ye, the artist formerly known as Kanye West, including the Horus necklace he wore to perform at the 2010 BET Awards.

Known for his ability to create flashy, larger-than-life jewellery, and despite various run-ins with the law for alleged money laundering and falsifying records, Jacob & Co has today transitioned into a respected maker of high end watches and now turns over more than $188million a year.

Alongside Arabo, there is Eddie Plein, who is credited with inventing the grill, with his removable gold fronts for teeth. Originally from Surinam, he put his dentistry training to use, founding Eddie’s Gold Teeth in New York, making 22-carat gold covers that encased three or four teeth at a time.

In the early 1980s, he was creating these fronts for the likes of Public Enemy rapper Flavor Flav, Big Daddy Kane and Kool.G.Rap. Shifting later to Atlanta, he continued with more elaborate grills for artists such as OutCast and Ludacris.

However, it was Ben Baller who took grills to another level, through his company If & Co. Real name Ben Yang, Baller started as a producer for Dr Dre, and was one of the people who signed Jay-Z to the label Priority Records, until he was fired and forced to sell his huge trainer collection.

Netting $1million from the sale, Baller set up If & Co in 2006, and his first major client was Mariah Carey. The company wesite reads, “we didn’t invent grills, we just perfected them,” it specialises in full customisation, including the “fully iced” option, which is smothered in white pavé diamonds.

In a sign of how far hip-hop has shifted into the realm of art, in late 2020, Baller collaborated with the celebrated Japanese artist Takashi Murakami, on a pendant and chain of pink sapphire, ruby, diamond and rose gold.

In 2021, he debuted a figurine necklace, made in collaboration with the street artist Kaws and the rapper Kid Cudi. Called Space, it is covered in diamonds and sapphires.

Traditional luxury brands had a somewhat uneasy relationship with hip-hop in the early days, initially reticent about being associated with the genre. A watershed moment came in 2018, when A$AP Ferg became the first hip-hop artist to be named an ambassador for Tiffany & Co, with the brand featuring Jay-Z and Beyonce in a campaign shortly after.

Tobak often gets asked why she would write a book that glamourises conspicuous consumption, by people who, she says, have missed the point. “Or, people will ask me, if all these rappers come from such humble beginnings, why would they blow their money on this?

“There’s a lot of coded language that people use when they talk about wealth for people that have not traditionally had it. There is a lot of judgment around people making money and breaking through these barriers,” she says.

“It’s more about the person asking the question and what they view as the world order of capitalism. It means you don’t understand what it means to suddenly be in a position where you’ve transcended your circumstances.

“I think that’s a beautiful thing,” she continues. “And as complicated as it is, that’s the American dream. I think what this story does is force people to ask themselves – who is the American dream for? Who gets to have it? It’s a much more complex story than conspicuous consumption.”

Canadian rapper Drake undoubtedly has the most impressive jewellery collection.

Among his many possessions is a 127.5 carat white diamond Homer necklace, estimated to be worth $2.3million, and the rapper was recently spotted shopping for a Life Cycle chain necklace by the Lebanese jeweller Nadine Ghosn, with prices starting at $38,680. He also owns the gold, diamond and ruby Crown ring designed and worn by Tupac Shakur during his final appearance in 1996.

When it came up for auction in July this year, Drake quietly dropped $1 million to ensure it was his.

Updated: August 11, 2023, 10:22 AM

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.