Free advice for America’s leading art museums. Not entirely free, following through could cost several million dollars. Consider it an investment.

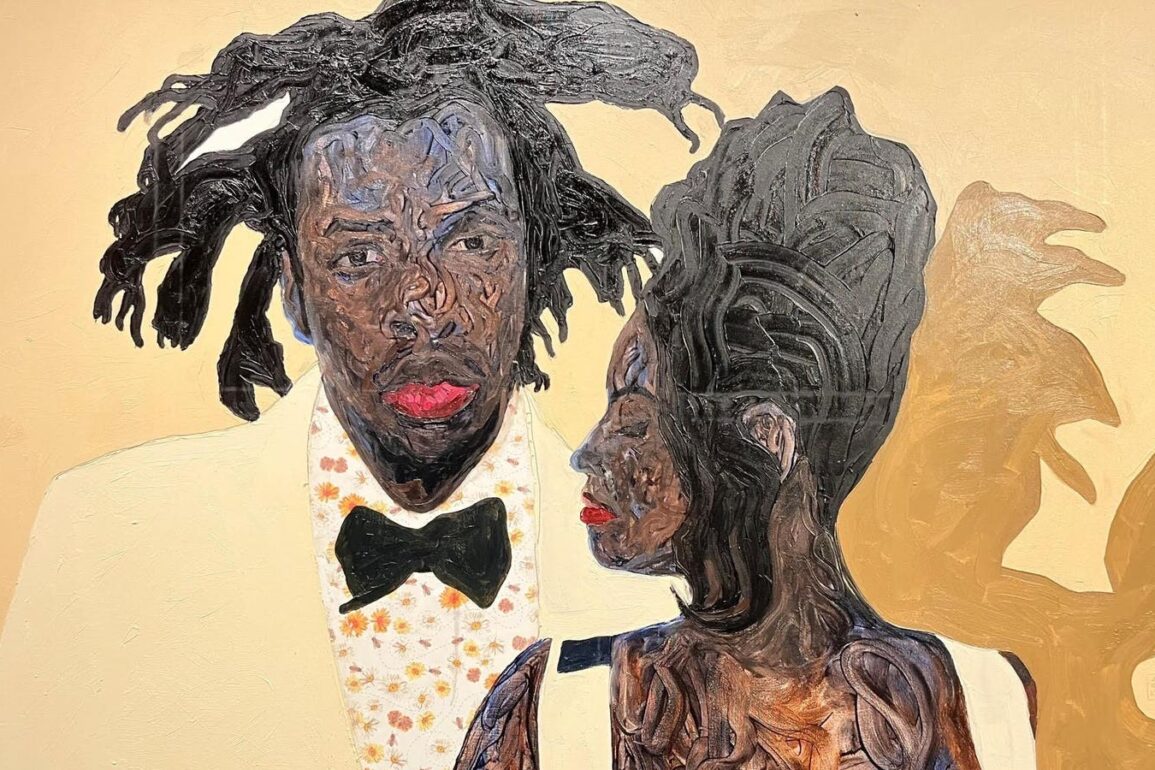

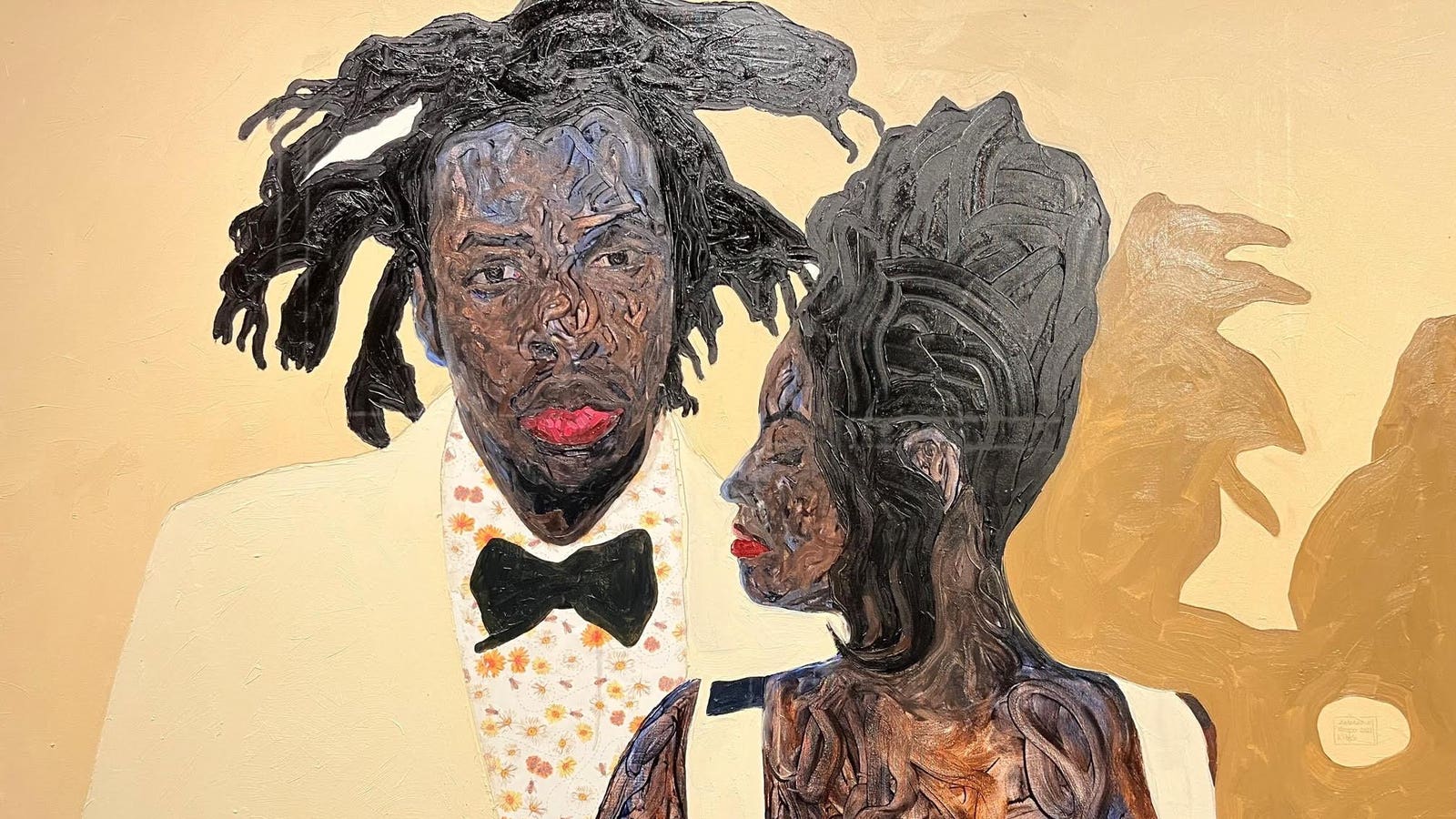

Amoako Boafo (b. 1984; Accra, Ghana) has a painting on view in his exhibition at the Denver Art Museum entitled Sunflower Bee Shirt. It depicts Jay-Z and Beyoncé in formal attire, their shadows casting an eerie silhouette against a pale backdrop.

The name comes from the bees buzzing about sunflowers patterned on Jay-Z’s shirt. It’s a double entendre. The female half of America’s No. 1 cultural power couple is known to fans as Queen B. Her fans, the Beyhive.

The unofficial portrait treats the pair with the scale, skill and seriousness accustomed royalty from the 17th century. The artwork is roughly 5-by-7 feet, composed sparingly, but richly, by one of the world’s leading contemporary artists in his signature finger paint style, and uplifts the duo to immortality. 7-7-7-7 on the iconic painting slot machine: the right artist, the right subject, the right style, the right size.

Sunflower Bee Shirt is Las Meninas for the 21st century, legendary Spanish painter Diego Velázquez’ bewitching, monumental portrayal of the Spanish king’s daughter circa 1656. What royalty was 400 years ago, celebrity is today. What Velásquez was, Boafo is.

The picture was deemed a masterpiece as soon as the paint dried and has headlined the collection at Madrid’s Prado Museum–one of the handful of greatest art museums in the world–since opening.

Comparing Sunflower Bee Shirt to Las Meninas risks marginalizing Boafo’s artwork by placing it into the dead, white, European, male canon to which it both does and doesn’t belong, but it’s the contextualization American art museums continue to honor and understand.

Amoako Boafo, Sunflower Bee Shirt, detail, 2021. Oil paint and paper transfer on canvas.

Chadd Scott

Sunflower Bee Shirt remains in the possession of the artist, meaning, for the right price and in the right place, the work is for sale. Any museum wise enough to acquire the painting should place it in the lobby, welcome the public to see it for free, and watch lines form around the block. Watch the museum’s relevance locally and nationally explode. Watch its social media status soar.

Watch as tens of thousands of people who’ve probably never stepped foot inside your building flip out over your purchase, a purchase which tells them they are valuable, their culture is valuable, youth is valuable, Hip Hop is valuable. You finally see them. They finally have a reason to see you.

Las Meninas for the 21st century and a calling card for the next 400 years.

Not bad for a few mil.

Free advice for art lovers and the Beyhive: don’t hold your breath. Go see Sunflower Bee Shirt in Denver before the exhibition closes on February 19, 2024, and the painting returns to Boafo, who-knows-when to ever be seen again.

Amoako Boafo

‘Amoako Boafo Soul of Black Folks’ installation view at Denver Art Museum.

Chadd Scott

Sunflower Bee Shirt is one of more than 30 paintings created between 2016 and 2022 on view in “Amoako Boafo: Soul of Black Folks,” Boafo’s debut museum solo exhibition. The exhibition’s title was inspired by civil rights activist, sociologist and Pan-Africanist W.E.B. Du Bois and his study, “The Souls of Black Folk,” published in 1903.

Boafo grew up near Du Bois’ burial site in Accra, Ghana, and was affected by his research, especially his coining of the phrase “double consciousness,” meaning the experience of Black people simultaneously having to look at themselves through their own and through white people’s points of view. Boafo’s artworks serve as an invitation to think about and challenge this “othered” perspective concerning Black people and the Black figure.

Denver’s installation begins with Boafo’s self-portraits.

“He started making these self-portraits when he was studying in Vienna and they started as this exercise of catharsis,” exhibition curator Larry Ossei-Mensah told Forbes.com. Ossei-Mensah is a fellow Ghanian introduced to Boafo years ago by Kehinde Wiley. “You have this Ghanaian artist who was going to Vienna, not a super diverse place, trying to find himself as a man, as a Black man, as an artist, and he had a lot of discourse with his professors who weren’t necessarily supportive of him making paintings of Black figures. He took a step back and made himself the subject.”

Boafo’s Egon Schiele-esq signature references his time in Vienna; it’s prominent size and placement–in Sunflower Bee Shirt it’s right in the middle, the empty space between Jay Z’s and Beyoncé’s shadows–a declaration of the artist’s authority and value.

The global art market would pick up on Boafo’s value in 2019, creating a frenzy for his work, making Boafo synonymous with a current condition whereby art speculators birddog young, Black, figurative painters like undervalued real estate, looking to cash in on a quick flip.

Finger Painting

Amoako Boafo, Ghana Must Go, 2017. Paper transfer and oil on canvas, 165 x 144 cm.

Kehinde Wiley Collection, NYC.

The oldest work in “Soul of Black Folks” comes from 2016 and is the only one on view painted entirely by brush. It’s excellent, but absent the swoopy, swirly, spaghetti lines of the artist’s subsequent finger paintings, lacks distinction. It’s a painting. Everything else in the show is an Amoako Boafo painting. Big difference.

The artist discovered his signature style by accident.

Boafo was invited to appear in a music video where he was asked to paint in front of the cameras. Not wanting to reveal his artistic secrets, he used his fingers.

“There was some satisfaction at what he created; he was like, ‘whoa, I might have landed on something,’” Ossei-Mensah explains. “He just kept working through it.”

Boafo’s earlier self-portraits share his vulnerability, his musings and inquiry about coming of age both personally and professionally. He’d paint with a brush in class and with his fingers at home. Some paintings are a mixture of both. Searching. A visual diary of sorts.

“As he builds his confidence, the mark making becomes more declarative,” Ossei-Mensah said.

He evolved into painting his subjects’ skin and hair entirely, literally, by hand.

No one else paints this way. Like Boafo. Not only the laying on of paint, but his subjects and the darkened hues of their skin tone, their locked-in gaze from the picture plane directly at viewers often set against a monochromatic background.

The art world calls this a “visual language” and Boafo has one all his own.

That’s the magic. The genius. In the 600 years in which humans have been painting on canvas or the tens of thousands of years they’ve been painting on walls with their fingers, no one has done it like Boafo before.

Foregoing the brush gives the work a different immediacy, an intimacy. Painting as caress. They articulate friendship, love, joy.

Removing the tool places the artist’s hand directly on the surface, no intermediary, no transfer, the artist becomes the artwork.

“There’s a kind of tenderness,” Vicki and Kent Logan Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Denver Art Museum Rory Padeken told Forbes.com. “If we’re thinking about histories of portraiture, those who receive their portraits are of a certain status in society and they’re declaring something to the world–that’s what portraiture is doing. (Boako’s portraits) are his friends and acquaintances or people he admires, and he’s painting their portraits, but using his hands. They’re direct. What does it mean for an artist to directly touch the paper or canvas to render a body? It means you’re imbuing the body with yourself.”

No one else paints like Amoako Boafo.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.