On Justified, the art of dialogue, and why Elmore Leonard’s work is such a natural fit for the screen

Raylan Givens walks into every room, every showdown, every tricky situation, knowing there is no one else more cool, more tough, more badass. For a modern-day deputy US Marshal, he fancies himself as an old-school sheriff from the Wild West. He is a self-styled Will Kane with a Stetson hat, disarming Southern manners and a flexible moral code. He is as quick with a quip as with a Glock. As the baddies prattle on, puffing their chests out, the lawman refuses to waste his words. By equating brevity with bravery, Raylan somehow elevates it to a heroic mode of being. Just when his near-quietness lulls the baddie into complacency, he sucks them in with carefully loaded words that manoeuvre them into a hostile enough position to legally warrant the use of lethal force.

It was less the weapons that Raylan and his friends, foes and frenemies came packing with, more the wielding of words and the silences between, that made Justified an instantly identifiable Elmore Leonard adaptation. Dialogue lent forward momentum, punctuated an immediacy, and gave shape to entire ecosystems in the crisp prose of the ace crime novelist. It was when his characters spoke, often meandering into impertinent anecdotes at right angles to the conflict, that they came alive.

So is the case on screen. Across the original six-season run of the sharp-witted, trigger-happy series, creator Graham Yost and his team of writers managed to capture what it felt like to read Leonard’s fiction: The irresistibility of laid-back coolness, the suspense of tension marinating, and the comic relief of point-blank retorts. Add to that the joyous pop of a line delivered with unmatched arrogance by Timothy Olyphant as Raylan. Take for instance how he lets a criminal know that he is not gun-shy: “I’ve shot people I like more, for less.” Or his response to a dying man who expresses shock on being shot in the back: “If you wanted me to shoot you in the front, you should have run towards me.”

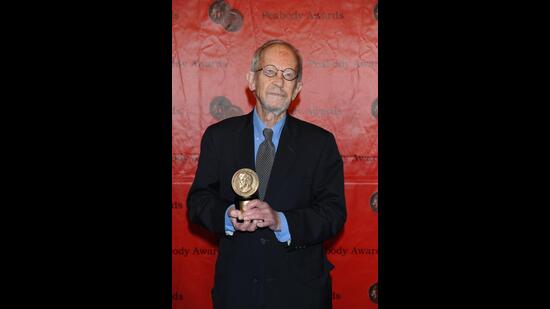

In praise of Olyphant’s performance, Leonard had said, “Timothy is one of the few actors who delivers the lines the way I heard them when I wrote them.” Leonard had similar praise for the writers: “I think it’s a terrific show. I’m amazed sometimes that they’ve got the characters better than I put them on paper.” What better recommendation can you get for a TV adaptation when the author himself declares he is a fan? Leonard in fact enjoyed Justified so much he was inspired to write fan fiction based not on his own literary creation, but the TV version. Raylan got his own eponymous novel in what turned out to be Leonard’s final book before his death in 2013.

20 years earlier, Raylan had first appeared as a bit player in the 1993 novel Pronto and brought back a couple of years later in Riding the Rap. But it was only in the 2001 short story Fire in the Hole that he took on a lead role. A small but characteristic detail in the story became the jumping-off point for the series. We meet the sharp-shooting marshal delivering his brand of tough justice in Miami. He gives a mafia enforcer 24 hours to get out of town. Once the ultimatum expires, he coaxes the man into giving him a reason to shoot to kill in broad daylight in an open-air restaurant. As punishment, he is reassigned back to Harlan County, Kentucky — the place where he was born and raised and hoped he would never return to. Where Leonard’s story had Raylan’s father die in a coal mine, Yost’s series revives him as a career criminal whose cold-hearted severity is what drove Raylan to become a career lawman. Returning to Harlan forces Raylan to confront the inner demons of a childhood spent under his father’s thumb.

Needless to say, there is no love lost between Raylan and Harlan. On the job, each double-dealing opportunist, each bribe-happy official, each criminal and each yokel out of their depth, Raylan runs into or chases down, help paint a picture of a community exploited by mining companies, neglected by urbanisation, and fuelled by an alternate economy of moonshiners, weed farmers and meth dealers. When you can’t escape such a bleak reality, you have no choice but to survive however you can. Characters resort to violence, urged on by old grudges, family feuds, desperation and greed. Dialogue lends a tribal specificity to the warring backwoods families who hold onto information like currency. Leonard’s work created a pathway for the showrunners to unpick the networks of opportunism run riot in the American heartland. Crime fiction, at its best, is rife with shrewd observations about the ills that sweep through all layers of society. It was Leonard’s grasp as a social critic that earned him comparison to Dickens, the same reason why Martin Amis once described him as “the nearest America has to a national writer.”

Over the seasons, Raylan crossed paths with a truly menacing rogues gallery, played by some truly exceptional character actors: Margo Martindale’s fearsome matriarch Mags Bennett, Neal McDonough’s bleach blond hitman Robert Quarles, Mykelti Williamson’s barbeque maestro Ellstin Limehouse, and Jere Burns’ tanned cockroach Wynn Duffy. But if there was one character that made viewers keep coming back to the show, it was Walton Goggins’ loquacious outlaw Boyd Crowder. One way to describe Boyd would be he is a car crash of a villain: He may be repulsive; you may be disturbed; yet it is impossible to look away. Boyd and Raylan worked the coal mines together as young men. Their subsequent lives diverging on either side of the law suggests Boyd is who Raylan could have become if he hadn’t escaped Harlan.

This uneasy connection from a shared history informs every encounter, cat-and-mouse chase and standoff. On Raylan’s return to Harlan, he starts an ill-advised relationship with childhood friend Ava Crowder (Joelle Carter) — a woman Boyd too ends up falling for. On the odd occasion, the two reluctantly join forces against a common threat. But it is when the two are trading friendly lines with unfriendly intent that the show feels most like an Elmore Leonard creation. Each rhetorical tug-of-war is a delightful testament to the chemistry between Olyphant and Goggins. Boyd prevaricating in stagey soliloquys with a certain baroqueness and a Kentucky drawl, like he was auditioning for a redneck Shakespeare production, made an ideal foil for Raylan’s mindful economy of words. “I’ve been accused of being a lot of things,” Boyd says at one point. “‘Inarticulate ain’t one of them.” Indeed. That Boyd was originally not supposed to last beyond the show’s pilot beggars belief. Just as he was shot dead by Raylan in Fire in the Hole, he was slated to suffer the same fate on the show. While giving feedback, Leonard recommended to Yost, “You might want to keep Boyd around.” That stay of execution is what made the show what it is today. For it is impossible to imagine Justified without Boyd. He was as much a face of the show as Raylan.

Which is why when Justified was rebooted this year, as all IP inevitably is in the boundless page-to-screen pipeline, there was some scepticism. The last time we saw Boyd, he was locked up in prison. Raylan, meanwhile, was working as a marshal in Miami so he could stay close to his daughter Willa. Justified: City Primeval puts Raylan on a collision course with a volatile sociopath on a rampage in Detroit. The sociopath, Clement Mansell aka The Oklahoma Wildman, is no Boyd Crowder, but he is played with a sleazy relish by Boyd Holbrook. The baddie and the premise are both pulled from Leonard’s 1980 novel City Primeval: High Noon in Detroit, with a few major to minor tweaks made here and there. The first one is making Raylan the protagonist, instead of Homicide Detective Raymond Cruz like in the novel. Second: he’s got his moping teenage daughter (played by Olyphant’s real-life daughter Vivian) in tow. He is eager to do right by her, but work as always comes in the way. He is eager to do things by the book, more so than before, but he also has to confront a madman with an even itchier trigger finger than his.

Where City Primeval does one better than its predecessor is how it reframes what was once reduced to a character foible as part of an institutional pattern in law enforcement. Does having a deputy US Marshal’s badge and a strict moral code justify Raylan taking on the role of judge, jury and executioner? Of course not. In the reboot, the murder of a judge — who had in his possession a little blackmail book with compromising information on half the officials, businessmen and power brokers in Detroit — exposes a dysfunctional justice system. When the system, with all its built-in checks and balances, is still prone to dysfunction, it can make anyone angry. In Season 1 of Justified, Raylan’s ex-wife Winona (Natalie Zea) tells him, “you’re the angriest man I have ever known.” This anger is recontextualised in the reboot, where Carolyn Wilder (Aunjanue Ellis), the Black attorney who is blackmailed by Clement into defending him, reminds Raylan how getting angry is a privilege exclusive to white law enforcement officers like him. “You’re angry. I get it,” she says, “I’d be angry, too. But everybody doesn’t get to be angry the way you do.” A similar sentiment is echoed by Wendell Robinson (Victor Williams), the Black detective Raylan is partnered with, when he suggests, “Sometimes I guess it takes an angry white guy to catch an angry white guy.”

As mentioned, it isn’t Raylan who chases after Clement in Leonard’s novel. In fact, he doesn’t even make an appearance. The novel’s protagonist, Raymond Cruz, however does appear on the show for a brief flashback and a quick conversation with Raylan. Cruz is played by Paul Calderon, who had first essayed the role in Steven Soderbergh’s 1998 caper Out of Sight — the gold standard of Leonard adaptations for the big screen just as Justified was for the small. What separates the great adaptations from the rest is good judgement to know what to change and what to keep to optimise the intrinsic pleasures of the cinematic medium. Right from the moment George Clooney’s suave bank robber Jack Foley and Jennifer Lopez’s US Marshal Karen Sisco meet cute in the trunk of a car, the film not only revels in the screwball comedy energy but also in the volleys of repartee lifted straight from Leonard’s novel. Soderbergh and his screenwriter Scott Frank scramble up the chronology to set up the stakes right away, and then let the sexy, tense, intoxicating chemistry between the two leads keep our eyes glued to the screen.

Out of Sight wasn’t Frank’s first rodeo when it came to adapting Leonard. It was the 1995 film Get Shorty, about a movie-loving loan shark (John Travolta) with dreams of becoming a Hollywood producer. Sure, the precedent had been set a lot earlier with films like 3:10 to Yuma (1957), Hombre (1967) and 52 Pick-Up (1986). But it was Frank who recognised the cine-friendly nature of Leonard’s written words and set the tone for adaptations that followed. As if on cue, soon came Jackie Brown in 1997, based on the 1992 novel Rum Punch, from a filmmaker who could very well be considered Leonard’s closest cinematic counterpart: Quentin Tarantino, whose first two films Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994) illustrated an equally sharp ear for dialogue and a similar penchant for undercutting moments of violence with humour. His third maintained a fealty to Leonard’s voice by taking liberties. Changing the title was the first sign of Tarantino’s desire to craft more of a character study. Changing the race of Pam Grier’s lead character from white to Black allowed him to pay homage to Blaxploitation flicks, while casting one of the genre’s undisputed icons as a stewardess who beats a system of racists, misogynists and criminals by playing them against each other.

Soderbergh said it best. “Quentin Tarantino’s rise has so much to do with Elmore Leonard’s world, as he would be the first to admit, that by the time a ‘real’ Leonard adaptation showed up in the form of Get Shorty, everyone had been prepared by Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction for that tone. Actually. Get Shorty, Jackie Brown and Out of Sight are textbook examples of what a director does, because all three feel like Elmore Leonard movies but are completely different from each other.” The same goes for Justified: the original six seasons and the recent reboot feel like Leonard adaptations but are not entirely similar either. The key to unlock why each of these adaptations works lies in the dialogue.

Prahlad Srihari is a film and pop culture writer. He lives in Bangalore.

Continue reading with HT Premium Subscription

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.