The 1950s, a golden period for fashion photography, introduced the world to names such as Richard Avedon, Lillian Bassman and William Klein. On the other side of the camera, a generation of models was emerging – women who were well-paid and continually photographed, and yet (unlike their counterparts of later decades) remained largely anonymous outside fashion circles. None perhaps more so than the American Barbara Mullen, who has died aged 96.

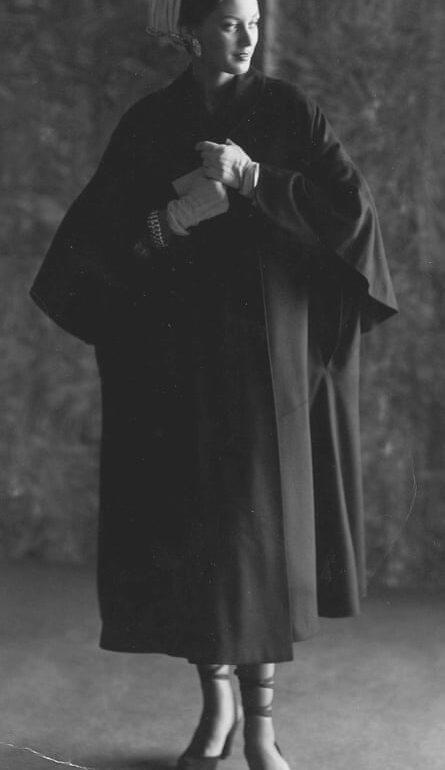

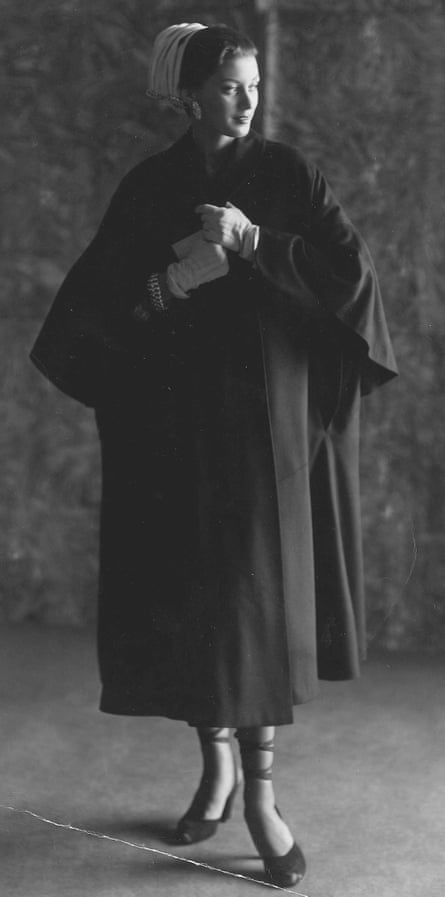

Models then were encouraged to have a recognisable, signature look. But Mullen was never considered a conventional beauty (“eyes slightly too prominent … tiny head, long neck and delicately elongated torso”, as the Vogue editor Jessica Daves described her) and did not think of herself as “photogenic”, as she told me when I interviewed her in 2013. Instead, she transformed herself for each job: a sleek, confident Manhattanite for Francesco Scavullo; a dreaming swan for Bassman, lost in the magic of French couture; a tongue-in-cheek clown for Klein, puncturing Vogue’s gloss with a scowl and a cigarette.

Her versatility meant she had a working life that spanned three decades and many shifts in fashion’s mood, from the film-noir romance of late-40s Manhattan to the sleek style of mid-60s Paris. She appeared on dozens of magazine covers, including Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, and thousands of editorial and advertising pages. But this quality also made her hard to pin down. “You can’t recognise her from one photo to the next,” Klein said.

Just as photography was being transformed by the arrival of smaller, faster cameras, Mullen’s long limbs and capacity for movement helped to shatter the poise and demure look of the era, creating shapes that often seemed as though the page could barely contain them. “I think there is an innate appreciation for form, for line,” Bassman said; she first worked with Mullen in 1948. “And those who are the great models – and there aren’t very many – they have it. Barbara had it.”

Mullen was born in New York. Her father, Matthew, left while she was a baby; her mother, Izma (nee Shirley), worked multiple jobs to support her two daughters, and died in a house fire in 1945.

After high school, Mullen began assisting at a local beauty parlour, which she quickly came to loathe. So when a passer-by stopped her on the street, and suggested she try modelling, she took the advice to heart. Within days, she had been hired by the department store Bergdorf Goodman, to model clothes for the designer Mark Mooring in their custom salon.

In 1947, Vogue chose one of Mooring’s evening gowns to photograph, but found it had been cut too small to fit any of the magazine’s usual models. So they tracked down the tall, thin mannequin on whom the dress had been made, and booked her for her first photographic job. The image of Mullen ran that October, next to a headline that announced “The New Beauty”.

Mullen soon became one of the industry’s most sought-after models. “It’s wonderful,” she enthused, in an early interview. “I make an average of $400 a week doing a job I’m crazy about.” In the years that followed that rate would double, as she became an early star of the Ford Modelling Agency. She travelled the world, shooting on locations from South America to India to the Caribbean. In 1949 she married James Punderford, a wine merchant, and they moved to Long Island.

Then, in 1955, at the peak of Mullen’s success, her husband died. She left the US to start over in Paris, just as many of her modelling contemporaries were retiring. There she continued to be in demand – working with Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, and also with newer titles including Elle, Grazia and Marie Claire. She worked with a new generation of US photographers – Henry Clarke, Bill Connors and Klein – as well as the Europeans Guy Bourdin, Sabine Weiss and Lionel Kazan.

Her retirement, in the early 60s, does not seem to have been a difficult decision: “Well, I couldn’t be a model forever.” By then, she had fallen in love again – this time with the Swiss Alps village of Klosters, and with a local ski instructor, Fredi Morel, who in 1962 became her second husband. She opened a fashion boutique, Barbara’s Bazar, which championed fledgling designers including Emanuel Ungaro, Sonia Rykiel and Kenzo Takada.

She continued to model on the side, and became a contributing editor at the Swiss fashion magazine Annabelle. But for the most part, she was happy to enjoy the easy pace of Klosters life, playing host to neighbours and visitors including Greta Garbo, Princess Margaret and Gore Vidal.

In the 70s, Mullen relocated to Zurich; from there, later on, she watched with detached amusement as the internet began to filter her work back into the world. In 2017, she became a cover star once more, when Bazaar used one of her Bassman photographs to celebrate its 150th anniversary. And, as a New Yorker at heart, she was thrilled when the image was projected on to the Empire State Building.

She enjoyed looking back, but was unsentimental about her modelling career. Trunks full of Chanel and Balenciaga were lost on foreign travels, her Charles James gown donated to a museum, and photographs given away to friends. By the time she and her husband left Europe for New Mexico in 2019, all that was left was condensed into in a single box of press clippings, contact sheets and tattered prints – and an exhibition invitation from Bassman on which she had scrawled: “To Barbara — the best of the best”.

Fredi died in 2019, shortly after he and Mullen had moved to the US.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.