Views: 13

For Black women in America, the stakes are higher when embracing your natural curls, it simply costs more — financially and professionally.

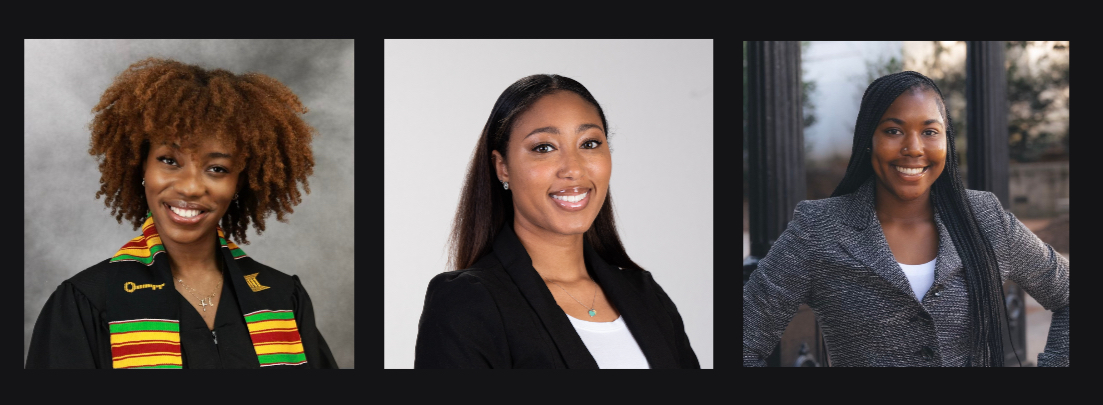

“What I have noticed, specifically being in Athens, is that the Black hair care products are more expensive than what I’m used to in Atlanta,” Kelsey Lawrence, fourth-year Anthropology and Criminal Justice major said. “When I visited the local beauty supply stores freshman year, I noticed a pattern of higher spending amounts compared to being at home.”

With Black consumers spending about 80% of their hair product budget at beauty supply stores, accessibility can sometimes be difficult for Black students at Predominantly White Institutions, or PWIs, in general.

I was going home my freshman year every single time to get my hair done – it was getting expensive to go home,” Niyah Brown, first-year Pharmacy student said.

The financial costs for Lawrence and Brown are one of the most difficult parts about maintaining their hair as a student, along with making the time to either do their own hair or travel to Atlanta for hair appointments.

According to a 2023 study from the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, “Black women spend 9 times more on ethnic hair products than non-Black consumers.” Not only does this excessive cost impact Black, female college students but it has a unique impact on Black people all over the world.

Beauty, History, and the Black Dollar

The Black beauty industry is a multibillion-dollar industry that has been an essential part of its culture for decades. But, the foundation of hair maintenance for the Black community can be traced all the way back to the transatlantic slave trade.

Within many African societies, hair was used as a tool of nonverbal communication and survival. The detailed braiding patterns and shapes of coily strands represented marital status, tribe, wealth and even age.

“Prior to the slave trade, hair was used to indicate your community,” said Vanessa Gonlin, colorism and hairism professor at the University of Georgia. “Oftentimes, those traditions are lost and you’re not able to express the community you’re a part of with your hair anymore … because the people who would’ve done your hair might be parted from you.”

Although the versatility of hair was recognized during enslavement, it was not necessarily for good reason. Not only were African people ripped away from their homes, they were stripped of the tools needed for hair maintenance.

Niyah Brown, second-year UGA Pharmacy School student, explains that many enslaved women were even forced to cut all of their hair off.

“In order to ridicule us and strip us of our identity they would shave their heads while they were on the ship,” said Brown.

Hair was an essential way of life — it was identity and beauty. And that still stands for a lot of African descendants in America today.

For Jonina Bullock, a recent graduate of the University of Georgia, these sentiments remain the same. She describes her hair as being a reflection of herself and a means of connection within her community.

I also love how my hair has connected me with so many people. It’s a form of connection for me and my mother, my sister, my family members…” Bullock Said.

But even today, just as it was during 15th century slavery, recognizing the beauty in Black hair is not always easy.

What is ‘Good Hair’?

The concept of “good hair” still seems to cause some division in the current culture. This concept implies that “good hair” means straight, loose curls and/or long hair. With eurocentric beauty being a standard in America, it has caused society to believe looser hair patterns are more beautiful.

For Kelsey Lawrence, fourth-year anthropology and criminal justice student at the University of Georgia, she believes there really is no such thing as “good hair”.

“The media glamorizes certain hair textures compared to others, so the public believes those are better than others, but all hair is ‘good hair’,” Lawrence said.

She also said that one’s ability to find confidence and embrace whatever hair texture they have, is what matters the most.

The monetary and emotional costs associated with the maintenance of curly and coily hair, is what seems to add an extra burden for these young women, and many others.

“When you talk to other Black women, part of the reason why they don’t go natural is because it’s really expensive,” said Niyah Brown. “It’s kind of like the pink tax. Same thing with black hair care products … they’re going to make it more expensive.”

A Lack of Hair Care Convenience

For Brown, Lawrence and Bullock, finding local stylists and budgeting for hair products is not easy, especially while on campus.

Finding someone who I trusted was pretty hard for me,” Bullock said as she reflected on her time at UGA.

These three women explain that the maintenance is especially difficult living in Athens, in comparison to a bigger city, like Atlanta.

According to a survey conducted by All Things Hair, 19.6% of Black/African American women travel more than 1 hour to have their hair styled. Additionally, more than half of women with coily hair spend more than $100 at hair salons.

The seemingly inconvenient and costly journey of caring for Black hair is one that stretches far beyond the boundaries of campus for these three women and Black women across the world – it seeps into the professional space too.

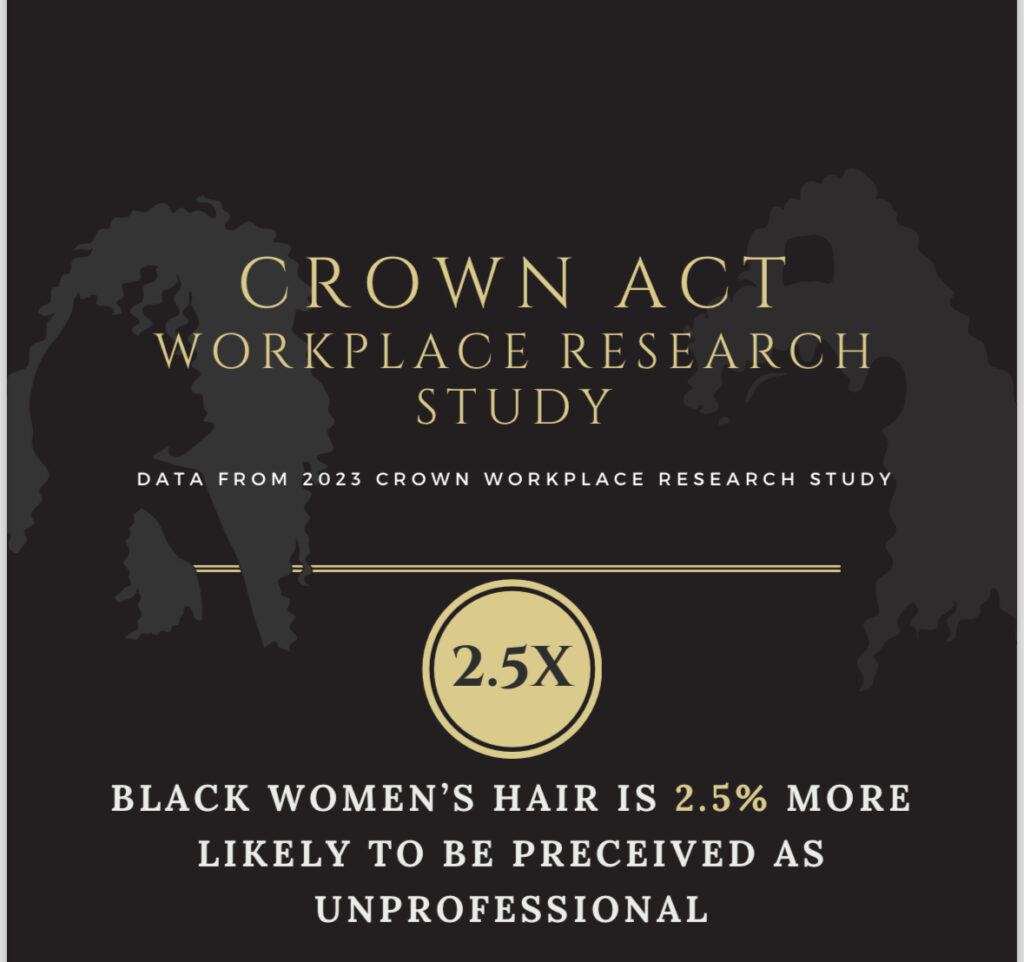

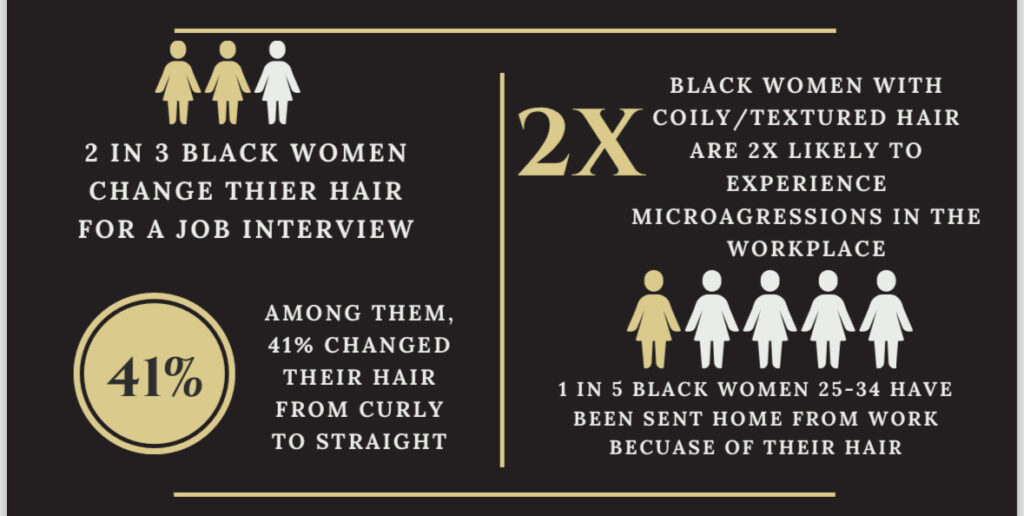

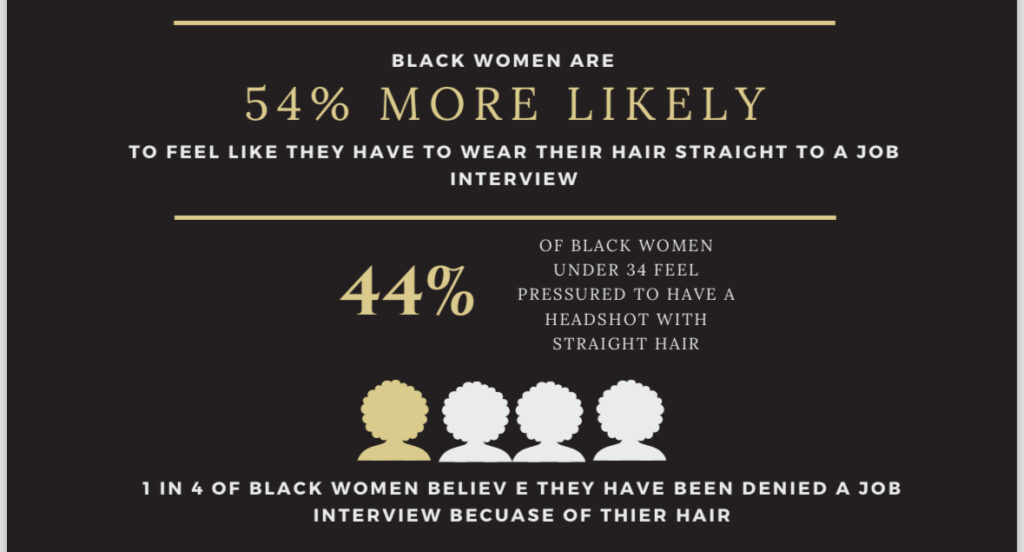

The ability to embrace natural patterns and new styles is not always easy in the professional space. In fact, the CROWN Workplace Research Study found that 66% of Black women change their hair for a job interview, with about 41% changing their hair from curly to straight.

Not only can there be challenges to nurture Black hair on a day-to-day basis, but there is also a perceived level of unprofessionalism associated with curly hair in the workplace, making the overall acceptance of Black hair even more difficult.

Hair inequality, hairism and texturism all encompass the discrimination minority women face because of the hair that naturally grows out of their scalps.

The efforts to combat this have been laid out under the CROWN Act which was created by Dove and the CROWN Coalition in 2019. This legislation was passed at the state level in California first, followed by 23 other states across the nation.

For Georgia, the CROWN Act is law in Clayton County, East Point, Gwinnett County, South Fulton and Stockbridge. Although legislation has been filed for votes in Georgia’s Congress, it remains one of the only states to not fully pass the law.

The real way that the CROWN Act can make change is if people allow it to change them,” Brown said.

As efforts toward nationally passing this law are still in effect, so are the efforts for Black women to continue changing the narrative on what their hair truly means in society.

Jessica Evans is senior political science and journalism double major at the University of Georgia.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.