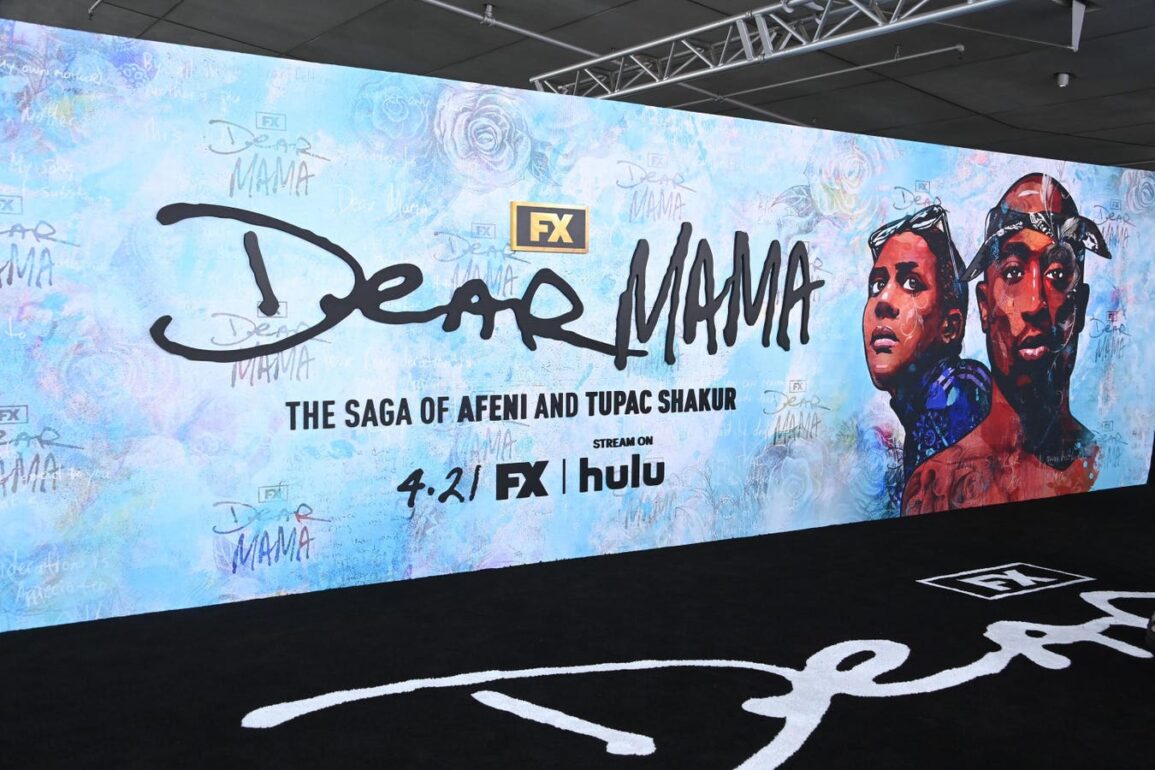

Just a few weeks ago, Dear Mama was named as one of the nominees for the Grammy for Best Music Film. It’s one of the rare potential winners that is also up for one of the other top prizes in entertainment, the Emmy. The FX and Hulu-owned production was so well-received upon its arrival in 2023 that everyone who saw it insisted it deserves recognition, and it may be headed for some wins in a few months.

Director and producer Allen Hughes is surely thrilled that he took on this lengthy project—it clocks in at more than five hours long—but he almost didn’t make the series at all.

“It kind of happened by mistake” Hughes stated when asked why he decided to produce this stunning docuseries. Tupac’s estate asked if he’d take on the responsibility of telling the late rapper’s story, knowing that the two had a history. That’s quite the honor, but Hughes was nervous. His first answer? “I said, I don’t think so.”

Hughes changed his mind when he came back to the Tupac estate and explained the kind of docuseries he wanted to make. Instead of focusing on hit singles, bestselling albums and chart positions—what the Emmy and Grammy nominee calls the “business of music”—he wanted to tell a dual narrative between the hip-hop titan and his mother.

It was a bold move, but one that proved to be a brilliant one. Throughout the five episodes of Dear Mama, the stories of both Tupac and his mother, Afeni Shakur, are presented side-by-side, essentially in equal measure. That might not be what some hardcore rap fans are looking for when they click on a Tupac-based series, but the estate took a chance said yes.

Dear Mama is not a typical music docuseries. It’s simultaneously much smaller than that—focusing on one man and his mother—but also much grander. It’s about the Black experience in America, how racism changes a man, a generations-long struggle, and ultimately, the love between a mother and son that stands up against drug issues, jail sentences, and countless conspiracy theories and untold press scrutiny.

I spoke with Hughes shortly after his Grammy nomination about the making of Dear Mama and the unusual and expertly-employed angle he utilized to shed new light on one of the most discussed musicians of the past several decades.

Hugh McIntyre: I enjoyed this series so much more than I thought I would, because I don’t know much about Tupac. I thought this isn’t really for me. Then, of course, I binged it and loved it.

Allen Hughes: Oh thank you. It’s interesting because I think that’s been a challenge. Even though it did really well for FX and Hulu. I think a lot of people felt like, either I’ve seen it or it’s typical hip-hop shit. So it was a challenge in that regard. It’s interesting to hear your reaction because I’ve heard that.

McIntyre: Tell me how you developed this and how you came to decide you wanted to tell this story.

Hughes: It kind of happened by mistake. The estate reached out to me via some mutual friends. They asked if I was interested in doing it, and I said, I don’t think so. I was developing this Marvin Gaye biopic. So I wasn’t looking at a Tupac thing and also just coming off of The Defiant Ones–after three years of how brutal it is sometimes to get things right in the documentary medium. I’m used to features. Documentaries are real people, real things. It’s tough. So I said, I’m not sure, I don’t know. Give me a few days to think about it. Then I thought about it and I was like, well, wait a minute.

There’s a lot of unanswered questions I have about Tupac. But if I can make this just as much about his mother–I was raised by a feminist activist mother, a single mother–and make it five parts about her history as well and explore him through her, then I’ll do it. So that’s what I pitched to them. And they were like, done, we love you. Then I got trapped into doing it.

McIntyre: It’s interesting to hear you say you really weren’t that interested because this comes across as the project of someone who was a student of Tupac. [Someone who] knew so much about him, had a clear admiration not just for his work but him as a man.

Hughes: Well I had that personal issue–you know, the challenge Tupac and I had when he was let go from Menace [II Society] and it got violent. [An altercation between Hughes and Tupac is detailed in the series] There’s a lot of fans out there throughout the years–crazy fans, fanatical fans–that have had it in for me a little bit. And my brother! I don’t know if I want to deal with that. And also I didn’t realize I had never dealt with whatever trauma that was.

And by the way, not just the incident, but just being young black males at that time, dealing with all the things we were dealing with, I just didn’t know whether I was, but ultimately I am a Tupac fan at the end of the day. How could you not be?

I was never a fan of poetry because I was never a fan of poetry. And there’s all these things I can go down the list that I discovered through the journey of making this series.

I was struck by, particularly on the Afeni side, I didn’t know any of that stuff and I didn’t know that history. So it ignited passions in me that I didn’t even know I had.

McIntyre: You mentioned your mother. When you came back to the estate and said, I’ll do this, was it your own history that made you decide that or what brought you to that route?

Hughes: They say when an artist paints a portrait, it speaks more about the artist painting than the actual subject, right? If you’re doing a biography on someone, everyone acts like they’re ot biased and coming with no prejudices or no luggage. But that’s what people are there for. They’re paying for your luggage. You’re coming with a point of view.

Of course I think it came from being raised by a single woman who was a feminist radical activist and on the forefront of the women’s movement. Of course. Hell, there’s a song, “Dear Mama,” about this incredible woman. We know about her struggles after her years in the Panthers, but we never get to hear about her years in her activism. We never heard about them.

Afeni was… You knew she was a Black Panther and you knew she struggled with addiction and then overcame it. That’s all we knew about her. It reminded me of my favorite film, The Godfather II. I said, wow, the sins of the father. If you explore the father and the son and do a dual narrative, in this case, the mother, the single mother and the only son, you’re going to find out a lot more about this guy than you would just by tracing a 25-year-old in his journey.

So yeah, it was personal. That’s a long way to say it. I’m a feminist by nature. I look at everything female-centric. I’m always thinking like, it’s not like the word inclusive has become so whatever. This genre almost became defined by toxic masculinity, including Tupac himself. Here’s this strong black woman that was ahead of her time. There’s something in there. There’s something he got from her and that’s how it came about.

McIntyre: Something that I realized after I finished watching this was, I don’t know much more about his music than I did going into it. This really was not focused on, I’ll say the music.

Hughes: Well, you know, it’s very musical. There’s a lot of music in it, and there’s a lot of his music in it, and then there’s a lot of this inventive stuff with his vocals, with the composer’s music, so it brings out the emotion and the poetry.

I made a conscious decision not to deal with the business of the music. And the business of the music is, then he made this album, and then they did this, they did 500 units, it went gold. And they’re like, we’ve got to pick the single for the next one, because we need to go platinum.

Who cares? It’s an emotional journey. It’s an emotional odyssey. It’s a musical odyssey as well. It’s an odyssey of activism. But the foundation of it is music, just not the business of music. And that’s what you’re referring to, those little signposts when you see the success and the numbers and what’s this album versus the last album?

His artistic journey is very much traced throughout the whole documentary. People talk about it. He talks about it. You see him evolving as an artist, you see him growing, but we don’t get into the business of the albums, never. Hearing you… No one’s ever clocked that, you know.

McIntyre: I clocked it because I am that guy. I write about charts and numbers and I have that in my head. I went into watching Dear Mama thinking, what were his biggest hits and where did they go? I’m still not sure, but I know so much about him as a man.

Hughes: We had to remind ourselves month to month, because there would be cuts with it in there. And I go, no business, take the numbers out. Because once we start doing one album, then you’ve got to track the whole thing.

I’s one of the things I loved about Brett Morgen’s Montage of Heck. I love that film. It was very inspiring to me. He’s not dealing with the business of the music. You’re feeling this essentialness of this artist. And you’re clearly in the music. But it’s not about the business.

It’s funny you bring it up, because it was a constant thing of trying to weed that out. You have to really be mindful of it.

McIntyre: Speaking of Morgen, his film that’s nominated this year uses the score in a similar way deliver emotion and crescendo in a way we really don’t get to see in music documentaries that much. Can you speak about working with Atticus Ross and weaving that into the storytelling?

Hughes: Atticus and his brother Leo [Ross] and Claudia [Sarne] all have been my composers for over 20 years and I love them. They’re like family. I remember Claudia saying she was nervous about it. She was anxious about like…what are the people going to think of our compositions with Tupac in it? We’re these white, rich [people] from the U.K.

I said, first of all, your guys’ music… The reason why I love working with them, it’s so soulful, Atticus, Claudia, Leo…what they do is transcendent. It has nothing to do with race or religion. It just soars in the most profound and almost melancholy way. All the stuff I’ve done with them has that feel to it. And I knew when we started messing with it, I go, this is a winner. This is bringing me closer to him.

I have this rule in the editing room. The editors, they’ll show me something and I say, you know what? I don’t think grandma can understand this. If a grandma can’t understand it, it’s got to go. So we think like our grandmothers. Can she understand what Tupac is saying right now? Can she understand what’s going on in the scene?

Then you realize once you strip the beat and the mute some of the hip-hop stuff away You can clearly hear what he’s saying. And it has this whole emotive thing that has really, quite frankly, never been done in hip-hop like that.

And then I heard from the fans. You hear from the real die-hard family friends. They really felt closer to him. I didn’t realize that was a byproduct of it. I was just looking for grandma to understand. But there’s this intimacy that’s gained in that approach as well.

Whereas with David Bowie, you still get that. But those songs…I think rock is easier to digest the lyrics for most people. Hip-hop is, unless you’re a hip hop band or it’s that one unique hip-hop track, if you want people to understand, it’s very difficult sometimes unless you figure out an alternative route to the lyrics in the poetry.

McIntyre: Hearing you talk about, can grandma understand it, and using the music to tell part of the story and how this isn’t a music business doc, it’s about the emotion…I’m hearing your work on features come through. It’s interesting that you brought so much of that learned experience to a doc where we don’t often see this type of filmmaking.

Hughes: It’s interesting too, Hugh, because the head of the estate, Tom Whalley, who signed Tupac back in the day, he was very supportive. The family was very supportive, but every now and then he would go, Allen, where are the hit songs? Where are they? They have to think about the business of it too,. And it is a business. I said Tom, I got you. I guarantee you in each episode, there’ll be two hit songs.

So I told the estate I go watch out, you’ll hear the hit. And it’s full fidelity, is what he’s really asking for. You’ll hear the hit. But I always found an interesting way to get in and out of it using the multi-track.

McIntyre: At what point did you realize that this was not going to be a two hour documentary, that this was going to be a lengthy project?

Hughes: Right from day one, the pitch was five parts. There’s this manuscript, which is now the authorized biography that just came out of Tupac. It was just a manuscript at the time that the estate shared with me. I saw all the childhood stuff and I saw a lot of the Afeni stuff in there. There’s no way to do this as a feature. Right off the rip, it was five parts.

McIntyre: I was surprised when I clicked it. I had no idea. I was further surprised because this was on FX as a five-part series. That’s unexpected. Was that ever a hard sell, either with the estate or selling the product?

Hughes: No. When I came back after the three days of thinking about whether I wanted to do it or not and called the estate back and said I’m in with these conditions–it’s got to be five parts and it’s got be a dual narrative about him and his mother, right away they were in.

When I went around town and met with all the streamers and networks trying to find the perfect partner, it was in the pitch. It was a very definitive treatment. And the byline also said, this is not a murder investigation.

That’s another thing outside of what you just clocked about the business of the music. I also was very conscious that this is not a murder investigation. We’re not getting into the conspiracy theories. We’re not relitigating any of the crimes or legal dramas. None of that stuff.

The irony of this being released late April, culminating on Mother’s Day weekend, I believe–I think it’s like a month or two later, the whole thing about Vegas and the murder investigation is opened. Like a month later. It’s nuts. We took that approach and then this happens.

McIntyre: What was a major misconception about Tupac that you aimed to make right with this?

Hughes: I think the number one misconception was that he’s a gangster. I knew him. Anyone who knew him knew he was an artist. But Tupac’s a method actor. He’s a performance artist. So the whole life…was a thing.

I don’t know how aware or unaware he was that he was embodying everything he was interested in, depending on what album it was. But I think the fact that he got cut down while he was on Death Row [Records] making those albums, the perception’s been that he’s a gangster and a gang banger. And I thought that did a disservice to his whole journey.

The estate gave me access to all his poetry, all his writings, his musings, his journals. You see when you read his plans for the future, Death Row was just a phase he was moving through. He had plans of moving on, having his own label, being very active in the community, opening up organic health food restaurants in the community–a lot of stuff with the kids and the culture. It was real clear in his writings that Death Row was a bridge out of prison and out of a stage he was in.

And you can’t force it. It has to be there. You see in part four…I think one of my favorite scenes is a nine-minute run where you go back to his performing arts high school in Baltimore, and he’s doing that movement piece to “Vincent” by Don McLean. And the acting teacher, Donald Hickins, is talking about his talent as a chameleon. Then you fast forward through his life and the displacement issues, and then you get to hit him up. And you get to Shock G talking about, you want a real man? And you see him become that. There’s that nine minutes of part four that is the thesis in answer to your question. You see the artist, the pure artist, become that dangerous guy that everyone thinks of.

McIntyre: Something you wanted to clear up is that he’s not this thing that he’s been called and that people see him as. Did he not want to be seen as that, though?

Hughes: That’s so funny, because there are scenes where he comes out of the courtroom and he’s like, I’m learning a lot about people’s inner fears about me being this gangster gang banger, You have “Thug Life” right on your stomach. That Gemini thing–he was a walking contradiction.

I always say, let’s talk about the business of music now. Tupac signed his record deal three years too late, in ‘91. He signed his record deal with Interscope. Tupac really was an artist that would have thrived in ‘88 when you had X Clan and Brand Nubian and Public Enemy was at their zenith. These real conscious Afro-centric hip-hop artists. Tupac signs his deal in ‘91 when gangsta rap is taking over. He’s smart and he was like, all right, let me figure this out so I can reach my audience. And that’s when he started making that shift.

McIntyre: I took away from it not so much that he’s not this thing, but rather, whether he is or not almost doesn’t matter because he’s also all these other things over here. You can be both of these things at once.

Hughes: That’s a big lesson I’m learning. Two things can be true. Both things can be true. Or multiple things can be true. I’m glad you pointed that out because who’s to say he wasn’t that? Who’s to say he wasn’t a thug or a gang banger? Because ultimately, even when you talk about actors or performers, for them to access something like that for it to be believable, it’s somewhere in there. You can’t just become something that’s that convincing and then not be rattling around somewhere in there.

My point is that’s not all he was and you can’t reduce it to that. When I looked around the world–I traveled a lot–in South America, in Europe, in Asia, and parts of Africa, there’s a mural. Tupac is everywhere, like none other. Beyond Bob Marley at this point and Che Guevera. What is that? Then it dawned on me. He’s become a global symbol of rebellion. I could never make sense of his last year, that last 11 months on Death Row, how it connects to the first 24 years. That’s the whole thing right there. A global symbol of rebellion. Those kids in Africa, they don’t speak that language. They feel him. And in France, they feel him. They see that struggle.

Ultimately that was the throughline that I was trying to reconcile with those last 11 months. How does this make sense, connected to all this activism? This thoughtful community leader that he was being groomed to be? And then it connected when I figured that out.

McIntyre: So your pitch was accepted immediately, the estate was on board, you had access to everything you needed or wanted. So what was the difficult part about making this?

Hughes: Damn, I’m trying to pick one. How do I put this in a sensitive way? When someone burns that bright, and then they just…they leave a lot of bodies in their wake. A lot of trauma. So I think the toughest part was… I’m very empathic, and it becomes this almost grief circle. It becomes this almost communal cathartic event that has to be managed at all times and–and you can’t manage spirits. It’s very difficult.

And you’re negotiating too because there’s a lot of people that don’t want to do the interview or don’t want to give up their photos. You think you have something and it slips through your fingers. We had access to the music for the first time. We had access to the poetry and the writings and the history, [but] that doesn’t mean you’re going to get everyone in his journey on board. So that was difficult. That was tough.

Also trying to find the melody in his narrative. That was always a challenge. Trying to find that in five parts–what’s the melody here? What’s the thing that makes sense? What needs to go away? That whole thing with the business of music needs to go away. There’s all these things that need to go away.

The toughest thing was connecting him in his mother’s narratives. That was the challenge. I never want to do another dual narrative in my life. That was tough. And these things are tough because you’re dealing with real people. You’re dealing with real family members. You’re dealing with people that were there when he’s in the hospital in Vegas. They’re in that room with him. That’s not a movie. That’s real emotions and trauma you’re dealing with.

Making movies is easy compared to documentaries. Everything is programmed. The craft service table is right where it always should be, everyone hits their marks, and it’s easy.

McIntyre: I absolutely teared up in the last episode, and I’m not one to cry at an FX docuseries.

Hughes: That’s so funny. That last five minutes with her Afeni alone got me, finally got me. Where she’s singing and doing the reading from the book at the same time. Oh man.

It’s easy to see what made Tupac so great or to celebrate Tupac or to find the darkness and the light and explore the duality. Someone that charismatic and that popular, it’s a layup. My goal was, how do we reveal her? How does she come out of the shadows and get her just due, given all that she did? Her history was erased. So I’m very proud that.

It was very thin, her narrative, compared to what it really is, you know. You see what a leader she was in that movement from ‘69 to ‘71. You learn in our film that we think that Tupac’s issues were not having a father only. You see it in a series of speeches that he has more anger for the men that abandoned him and his mother in the movement. That her comrades turned their back on her.

McIntyre: I’m not even going to say I am a fan of Tupac, but I loved the journey of learning about him.

Hughes: Yeah, sure. You’re our target audience.

McIntyre: Really?

Hughes: I remember having this discussion with Dre, it got very heated on Defiant Ones. He didn’t understand why I wanted to make it for people that weren’t fans of his. I’m like, your fans are in, dude, that’s easy. When I’m approaching these things, grandma’s one person, but you’re another person. People who aren’t a fan of Tupac and aren’t even a fan of hip-hop. Every month in the editing room, I would say that too. I’d say, we have to keep in mind, there are people coming to this–there are people I want to come to this that don’t even like hip-hop, let alone Tupac. So we have to keep that in mind, keep that in mind. It’s rewarding and I hope more people see it. Like I said, it did really, really well for the network. We did really well, but that whole other thing that’s you, her, and him, and grandma, I think we still have yet to reach.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.