Prince was at a crossroads. His extravagant Lovesexy Tour lost big money in 1988-89, and he fired his longtime managers. His third film, 1990’s “Graffiti Bridge,” collapsed at the box office. Then, after a stripped-down tour of Europe and Asia, he dismissed his band.

So, in 1991, Prince once again decided to reinvent himself with a fresh group, the New Power Generation (NPG), featuring mostly Minneapolis musicians, including his childhood idol and mentor.

“He was definitely searching for something new,” said NPG bassist/guitarist Sonny Thompson, who had given Prince some guitar and vocal tips when they were teens. “He wanted [the sound] to be a little more gritty, a little more street, just a little. A little bit of rock. And little more technology, some samples here and there.”

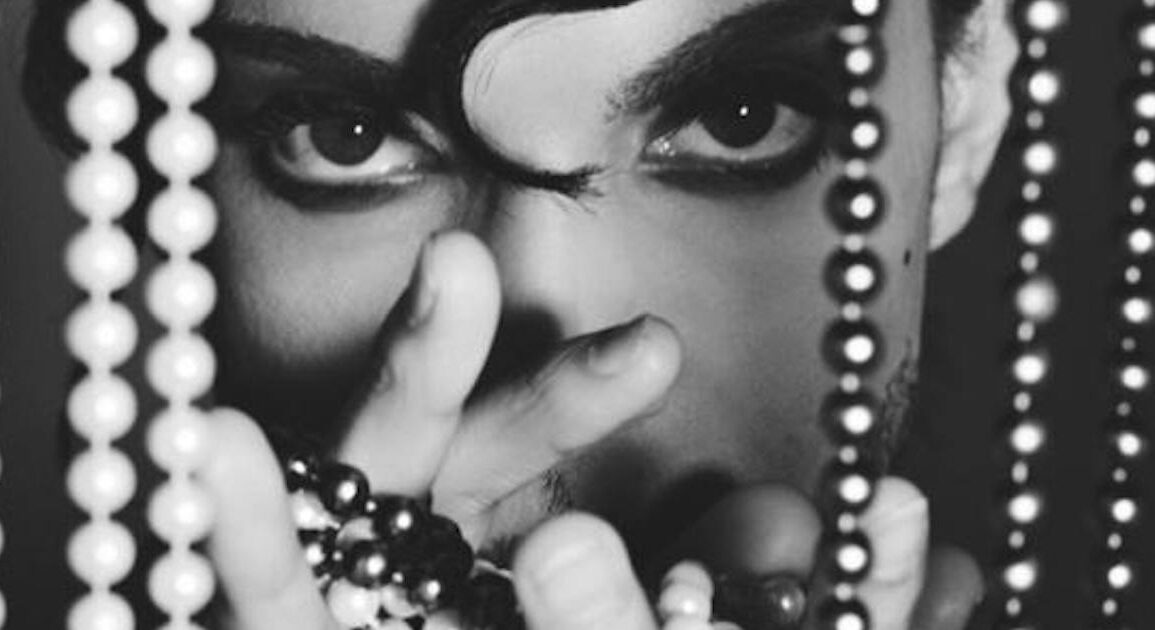

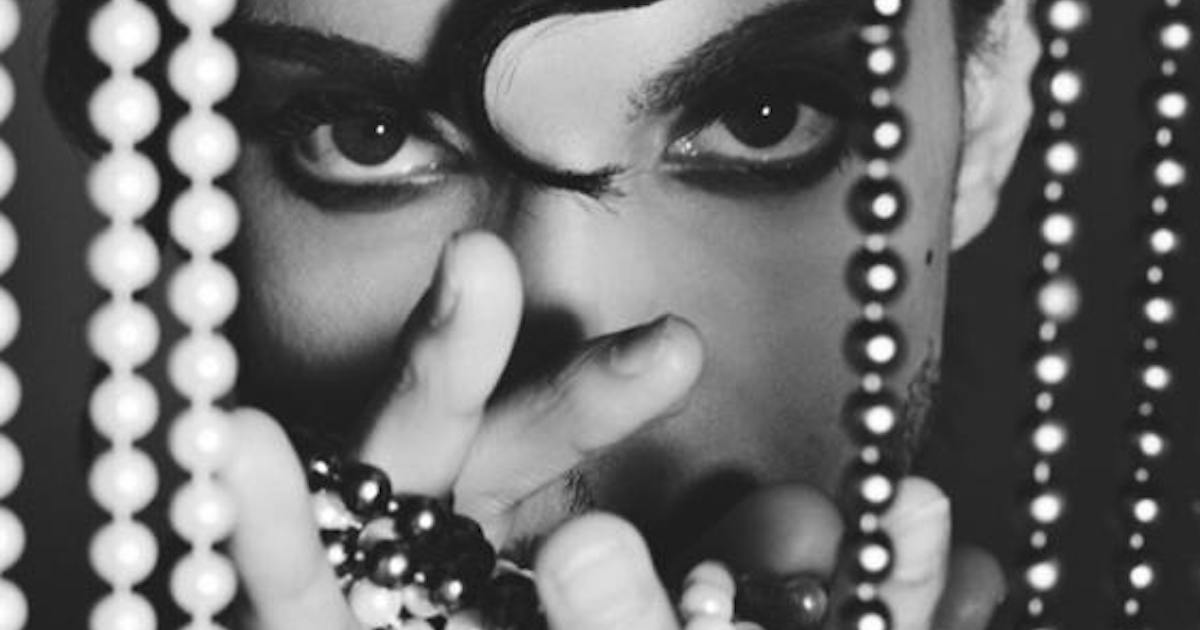

Prince and the New Power Generation created “Diamonds and Pearls,” a typically eclectic Purple project embracing pop, funk, soul, rock, gospel, jazz and, for the first time, hip-hop.

His 13th studio album — featuring “Cream,” “Gett Off” and “Money Don’t Matter 2 Night” — is the subject of the latest posthumous reissue from the Prince Estate, with the super deluxe 12-LP disc version ($349.98) or super deluxe 7-CD disc version ($159.98) containing 47 previously unreleased tracks, a live recording and a Blu-ray of a Jan. 11, 1992, concert at Glam Slam in Minneapolis, the NPG’s official debut.

The introduction of hip-hop into Prince’s oeuvre may have been more accidental than intentional. Minneapolitan Tony Mosley, who was a dancer on Prince’s Nude Tour in 1990, was goofing around at a soundcheck in Paris rapping “The Humpty Dance,” a then-hip-hop smash by Digital Underground, and Prince entered from the back of the arena.

“I thought we were going to get into trouble,” Mosley remembered, “but he called me into his dressing room and said, ‘I didn’t realize you rapped, and you have good presence. What do you think if we add that to the set when I do a wardrobe change?’ That was my opening.”

Prince kept asking Mosley to write raps — both for Tony M., as he was billed, and Prince himself.

Adding rap calculatedly “reassociated Prince with his Black audience,” said drummer Michael Bland, who was recruited then for the NPG as a 19-year-old Augsburg College theology major.

But incorporating hip-hop was controversial because Prince had criticized rappers in “Dead on It,” a song on his infamous “The Black Album,” that was recorded in 1987 but withdrawn, though widely bootlegged.

“The hip-hop community surely didn’t want to hear from Prince because they felt dissed,” Mosley said.

But the boss was fearless, the aspiring rapper learned.

“The best piece of advice he gave me at the time was ‘Write for yourself, do not write for a particular demographic. Write from your own experiences.’ He was looking for a fresh cut, and he wanted it to be from Minnesota.”

Another key move to plug into Blackness on “Diamonds and Pearls” was adding Rosie Gaines, a powerhouse vocalist/pianist from the San Francisco Bay Area.

“That was [Prince’s] first full cup of soul — not a half-cup — that he could shape any way he wanted to,” said guitarist/bassist Levi Seacer Jr., the lone holdover from Prince’s previous band and a former bandmate of Gaines from the Bay Area.

“Rosie brought that church, jazzy singing style,” Thompson said. “She changed the dimension of his music. She’s a real singer. Not saying anyone else before her wasn’t. She could just bring it.”

‘Cream’ rises to the top

Hip-hop wasn’t the only potential hiccup for “Diamonds and Pearls.” When Prince submitted the album to Warner Bros., his record label, there was pushback, a not unfamiliar spot for the maverick Minnesotan. Label chief Mo Ostin didn’t think the record had a surefire pop hit. Knowing that Prince could be prickly, Ostin phoned Seacer, NPG’s music director, to deliver the message to Prince.

“How am I supposed to tell him that? So I waited a day to think about it,” Seacer said.

Of course, Prince was upset but he went into a Paisley Park studio all by himself and then beckoned Seacer the next morning to hear a new song.

“‘You did that last night?'” Seacer wondered.

Said Prince: “‘Yeah. You think Mo will love it? FedEx it to him.’ “

Ostin loved “Cream,” and Prince headed to Los Angeles to create the song’s video, for which he selected two female dancers who looked like twins but weren’t. He dubbed one “Diamond,” the other “Pearl.”

“He shared that he thought our names were apropos because Lori [Elle] was a jewel and just needed to be shined up a little bit for her to sparkle,” said Robia Scott, a then 20-year-old Los Angeles dancer, “and I was like a pearl — a little bit of a tough exterior but when you break through that, there is this beautiful gem inside.”

Scott and Elle were soon summoned to Minneapolis to pose with Prince for the cover photo of “Diamonds and Pearls” — a hologram that required a rotating platform during the photo shoot, because Prince being Prince, he wanted something special.

The two dancers joined the ensuing concert tour, which, unexpectedly to them, also included belly dancer Mayte Garcia, a teenager who would become Prince’s wife in 1996. Moreover, Scott and Elle became “the voice for the album,” as Scott put it, because they, not Prince, did interviews to promote the project.

To Warner Bros’ delight, “Cream” rose to No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot 100. In the new boxed set, there are three different studio versions of “Cream” as well as three live renditions.

Recruited from local bands

Another single, “Diamonds and Pearls,” ascended to the top of the R&B charts. It was recorded before NPG musicians were officially hired.

Bland, recruited from Dr. Mambo’s Combo at Bunkers bar in the North Loop, and Thompson and keyboardist Tommy Barbarella, both poached from the Steeles’ backup band, were enlisted by Paisley Park to play behind legendary Mavis Staples, who opened for the Nude Tour. One day after rehearsal, the three musicians ended up in the recording studio with Prince for the first time, cutting instrumental tracks for three tunes, including “Diamonds and Pearls.”

“I remember thinking that it was like a Christmas song or something,” Barbarella said. “You had no idea what it was going to be.”

Without consultation, the Purple One dubbed the pianist “Tommy Barbarella,” whose surname is Elm. He learned of his new moniker from a photo in a newspaper.

“My mom called me and said, ‘There’s a picture in the paper and it looks like you and it’s not your name.'”

Not only did Barbarella get a stage name, but he was also the only white musician in an otherwise all-Black ensemble. He felt the pressure, especially early on at a Black music conference in Atlanta where he accompanied Gaines on Aretha Franklin’s “Ain’t No Way.”

“I remember being just terrified,” the pianist said. “It was a very exposed moment in an all-Black crowd. That was the most scared I’ve ever been in my life performing. I wanted to be legit, as if being in Prince’s band didn’t make you legit enough.”

A tribute to Miles Davis

The new boxed set includes outtakes like the blues “I Pledge Allegiance to Your Love” (“We played ‘Summertime’ and Ray Charles songs at soundcheck,” Barbarella says), the silly “Work That Fat” (a rap parody by Prince) and the jazzy instrumental “Letter 4 Miles” (saluting trumpet icon Miles Davis, who was friendly with Prince).

“Prince and I recorded [‘Letter 4 Miles’] with no one else around,” Bland recalled. “He was on piano and I was on drums and he said, ‘Let’s swing it.’ We tried it a couple times. We went into the control room where he proceeded to put bass on it and he asked me: ‘You ever arrange horns before?’ ‘No, I’d love to try.'”

After four consecutive albums under his own name, Prince gave the New Power Generation billing on “Diamonds and Pearls” — just like he had with his earlier band, the Revolution, on three collaborative albums. That meant artist royalties for the NPG musicians.

Bland continues to receive checks, maybe a few hundred dollars here, 50 bucks there.

Mosley pocketed bigger payments because he, like Seacer, earned co-writing credits on some songs.

“It was eye-opening; I took a picture of it,” Mosley said of his first check. “My first big one was over 100K. A kid from north Minneapolis to see something like that. … I think I like this writing thing. I think I’ll do this more often.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.