Recent relevant markets defined by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) should cause concern. From online superstores and virtual reality dedicated fitness apps, the lines around relevant marketplaces are increasingly creative. More recently, the agency breaks form, not by inventing a market, but rather by ignoring the impossibility of quantifying differences in aesthetics. Given consumer preferences and differences in personal style, developing an economically reflective relevant market in the handbag space is about as likely as convincing a Chanel connoisseur to shop at Walmart.

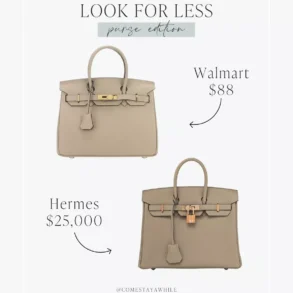

The most recent complaint focuses on the proposed merger of Tapestry Inc. and Capri Holdings, which would bring the fashion brands Kate Spade, Michael Kors, and Coach under one umbrella. The FTC asserts that this would reduce competition in the relevant market for accessible luxury handbags. The agency defines an accessible luxury handbag as “one that is crafted predominantly in Asia from high-quality materials with fine craftsmanship at affordable prices.” What makes a price affordable isn’t specified, but the complaint states mass-market offerings are typically under $100, meaning accessible luxury would likely start around that price point.

At first glance, the category of accessible luxury is not a new idea. Back in 2003, the Harvard Business Review examined the phenomenon of “luxury for the masses,” and credited it to the growing purchasing power of the middle market. The same article also emphasized that to excel in this market, brands had to reach both up and down in their pricing, meaning that these brands often reach differently priced consumers all under one umbrella.

According to the websites of these brands, prices range from less than $150 to over $500 for Kate Spade, almost $3,000 for Michael Kors, and $10,000 for Coach. Based on prices alone, these three brands would appear to operate in different markets depending on the product, or at the very least target different customers.

Apart from prices, the lines the FTC draws around the relevant market seem arbitrary and contradict themselves. Limits include the requirement that a brand sells on multiple sales channels and has a no discounting policy. Under such specifications, the FTC asserts that true luxury brands, such as Valentino, would not be competitors.

However, Nordstrom was listed as a retailer of accessible luxury brands in the FTC’s complaint. Nordstrom sells Valentino purses, at price points that overlap the more expensive offerings of Michael Kors and Coach, and as of this writing, two of the bags were on sale.

An overall focus on price without additional qualifiers would eliminate such contradictions and avoid the difficulty of trying to categorize subjective terms such as craftmanship, or fine materials. However, an even bigger hurdle is trying to determine what consumers would find interchangeable – a key principle to defining markets.

According to Harvard Business School professor Gerald Zaltman, purchasing decisions are not driven by logical comparisons, but rather by how the product makes consumers feel. Products that can evoke an experience of connection or bonding may be more successful in converting customers than technical superiority.

In the book, The Substance of Style, Virginia Postrel looks at the value and utility consumers gain from aesthetically pleasing products, the author notes, “To the chagrin of designers, it’s hard to measure the value of aesthetics, even in a straightforward business context. Often look and feel change at the same time as other factors, making the specific advantages of each new characteristic hard to isolate.”

Together, these insights show that while the technical aspects of a product matter, the feeling of a product is also important to consumers. The trouble with determining markets in fashion is that the aesthetics and subsequent feeling of an item matter for interchangeability. Kate Spade offers novelty handbags shaped like animals or foods. It is unlikely that an animal-shaped Kate Spade purse provides the same feeling – and is, therefore, a reasonable substitute – for a neutral bag from Kate Spade, let alone a different item from Michael Kors or Coach.

For the FTC, which is already treading in the ambiguous territory of design, additional qualifiers such as sale policies or subjective terms such as craftmanship complicate an already difficult market definition. However, no tweaks to the definition can get around the glaring reality that aesthetics are subjective.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.