Drake’s Era of Masculine Frustration

In 2019, Drake sat down in his Toronto home to record a rare, career-spanning interview with the journalists Elliott Wilson and Brian (B.Dot) Miller for their “Rap Radar” podcast. Much of the sprawling two-hour conversation was spent reflecting on Drake’s early successes and the unconventional path that he took to dominance. When Drake started making music, he was both celebrated and dismissed for favoring the sounds of R. & B. over hip-hop, and for balancing swagger and vulnerability—a move that felt daring at the time, but that eventually became the standard in the world of radio rap. “To me, making music for girls is just the waviest thing you could do,” Drake told the interviewers, making no apologies for his affection for R. & B. and his tendency toward openheartedness. “Of all the things people could say about me, I was never affected by the whole ‘This is soft, this is emotional,’ or whatever. I guess I could just make music for dusty guys or whatever, but that’s not what inspires me.”

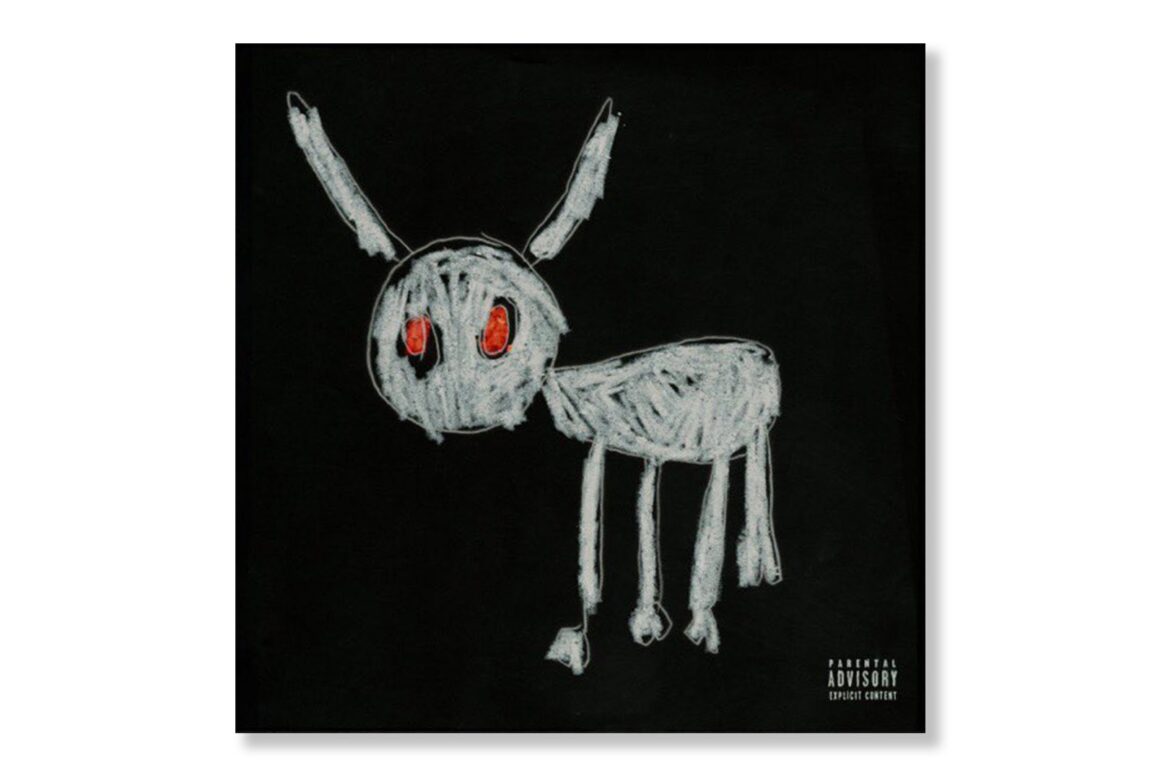

Four years and three albums later, though, Drake no longer seems particularly interested in making the sort of soft, emotional music that connected with a more feminine sensibility. His most recent releases, “Her Loss” (a 2022 collaborative album with the Atlanta rapper 21 Savage) and, out just this past Friday, “For All the Dogs,” are embittered documents of masculine frustration. Drake, perhaps the most influential and commercially successful artist of his generation besides Taylor Swift, has conquered all there is to conquer within music, but he sounds more dispirited than ever—even deadened. The record begins with the musician making a stony rebuttal to a woman who claimed that he should have treated her better. “Nope,” he grunts. It seems particularly lonely at the top for the thirty-seven-year-old Drake, who telegraphs alienation in both his professional and romantic lives.

In the past, Drake would couch this sort of self-indulgence and acidity between unimpeachable pop hits, impassioned freestyles, and playful genre experimentations. But there is a stylistic stubbornness to “For All the Dogs,” which drifts moodily for nearly ninety minutes, with little refuge to be found in the sorts of spirit-raising Drake anthems that have populated the charts for a decade and a half. Occasionally, on this record, he will slip into an unexpected mode, such as on “Gently,” a song in which he raps in Spanish over a hiccupping dembow beat alongside Bad Bunny. Here and there, the beats venture into bracing East Coast styles of the moment, such as drill or Baltimore club, adrenalizing the record for brief moments. But the rest of the album ambles through a signature haze of dreary, mid-tempo beats and meditative piano-lounge instrumentation perfected by Drake’s go-to producer and chief partner, Noah (Forty) Shebib.

Across the album’s twenty-three tracks, Drake returns to the same hardened sentiments. “I don’t like the tone of your replies,” he tells a woman on “7969 Santa.” Later, on a single with SZA called “Slime You Out,” he delivers an almost comically disdainful riff: “I don’t know what’s wrong with you girls,” he announces. “I feel like y’all don’t need love / You need somebody who could micromanage you.” Drake, ever the savvy architect of his own image, must have sensed that this song was a step too vitriolic, and invited SZA onto the track to play the female foil. There is such a comprehensive joylessness here that “For All the Dogs” almost plays like a concept album about a parody of Drake’s disaffection rather than a sincere exploration of his psyche. On one of the album’s final songs, “Away From Home,” Drake takes four minutes to ruminate on the days when he was not yet successful. “I was on a Greyhound way before the jet / Buffalo, New York, was like the furthest I could get.” It’s a raw but expertly executed performance, and Drake sounds full of life, though only when he is thinking about the days when he still experienced some hunger and yearning.

The rapper is trying to have some fun on this record, though—or at least he is trying to amuse himself. As Drake has grown commercially unassailable on streaming platforms, he has become fond of using his influence in crafty ways. On “For All the Dogs,” he Trojan-horses as many inside jokes and esoteric references as possible into songs and interludes. The album includes a long recording of a woman petulantly complaining about a free vacation that she took; a snippet of Drake’s six-year-old son, Adonis, rapping nonsensically; and a clip of Snoop Dogg role-playing as the drowsy host of an imagined radio station called “B.A.R.K. Radio.” These winking refrains and thematic Easter eggs don’t always add up to much besides distraction, and the record is suffused with a listlessness that Drake himself sums up on “First Person Shooter,” which features J. Cole. “Big as the Super Bowl,” Drake boasts. “But the difference is it’s just two guys playing shit that they did in the studio.”

And yet, when not creating studio albums, Drake appears to be amusing himself quite successfully in other mediums. Where other stars of his magnitude tend to disappear to help sustain their relevance by way of intrigue, Drake has worked tirelessly to keep apace with his younger, more prolific streaming-era descendents. As his career has advanced, his ambitions have morphed and escalated, and the past few years have brought increasingly elaborate media high jinks and crafty public-relations stunts in addition to music. During the promotional run-up to “Her Loss” late last year, Drake and 21 Savage concocted an impressive collection of high-budget parodies. They released a glossy, fake edition of Vogue for which they were sued on copyright infringement (they settled out of court for an undisclosed sum), a mock teaser for NPR’s beloved Tiny Desk concert series, and a staged imitation of a “Saturday Night Live” performance. Right now, Drake’s most energetic and joyful artistic innovations are happening outside the recording studio.

Since his early days as an earnest, overly emotional upstart, Drake has made it all too tempting for fans and critics to armchair-psychoanalyze him and extract judgments about his character. He is an actor skilled at cultivating intimacy with his listeners, making it easy to overlook how he is still, above all, a performer—one who enthusiastically slips into a preferred role or a mask that will suit him during a given period of his career. After all, he made his début in the spotlight as a character on the Canadian teen show “Degrassi,” and he has always cited Jamie Foxx—a polyglot known for his broad showmanship—as his greatest inspiration. “For All the Dogs” must, in many ways, be another one of Drake’s performances, and a part of an artistic era as much as—or more than—a real-life one.

And yet some of his discontent has spilled into the real-life discourse around “For All the Dogs” during the last week. His long-running rivalry with the New Jersey rapper and podcast host Joe Budden was reignited when Budden offered a searing assessment of the record: “[Drake is] rapping for the children,” he said. “I had to look up how old this nigga was when I finished listening to the album. . . . You’re gonna be thirty-seven years old.” Rather than ignore the comments, Drake indulged the surly and discontented version of himself who appears on “Dogs,” firing back a long-winded Instagram comment that verged on cruel: “This guy is the poster child of frustration and surrendering,” he wrote. “This is a man projecting his own self hate . . . I own a 767 . . . he owns a modest house—and flies first class on special occasions.”

It was another long-simmering reversal for Drake, who, in the “Rap Radar” interview from 2019, reminisced about his early style of rapping. “You know, you can always hear a rapper finding themselves, if you give them five or ten years,” he said. “I used to try to rap like Budden back in the day, just the way I used to try and get certain flows off.” In Budden, he still might be reminded of his former self—who is perhaps the most stubborn foe of them all. ♦

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.