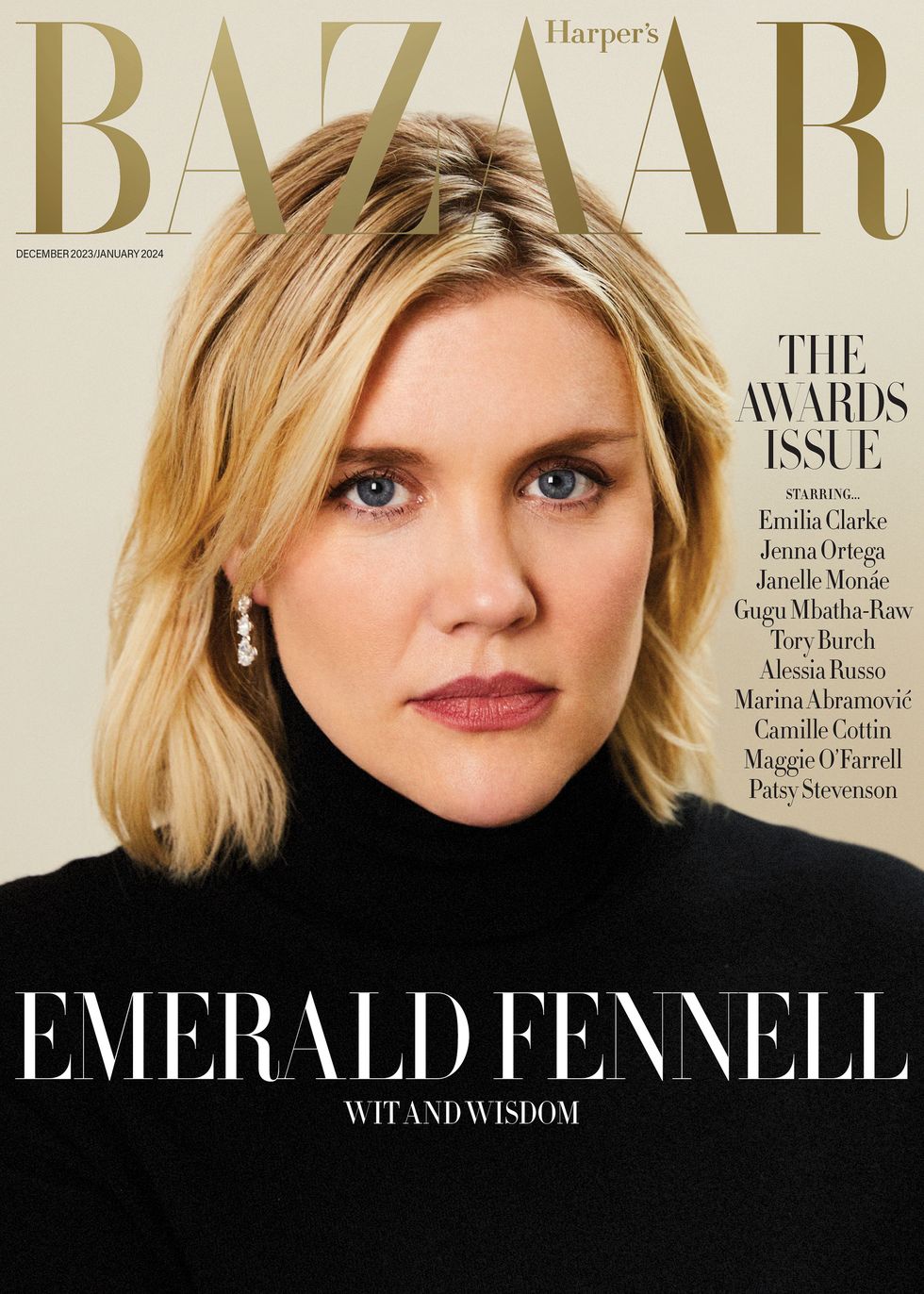

“Definitely kedgeree! Way more delicious,” Emerald Fennell instructs me – and, to some degree, our waiter – in Soho’s Dean Street Townhouse. Breakfast decision made and order duly taken, she turns to me, wide-eyed with mortification. “Oh my God! I’m so sorry. It’s like I’m your controlling boyfriend. Obviously order what on Earth you want.” Within minutes, the director, writer and actress and I have gone on to review other inadmissible male moves on a date, and how to handle power imbalance in the moment.

Fennell, I soon realise, is a stellar conversationalist – which makes sense for someone known for the crackling dialogue in her scripts. She clearly brings a great deal of herself to her projects – starting, on a cosmetic level, with the contralto RP she deployed to play Camilla Parker Bowles in The Crown. Moreover, I witness much of the empathy and emotional honesty shown by her Call the Midwife character Nurse Patsy; the fierce feminism that underpins 2021’s Promising Young Woman, her directorial debut, for which she won the Best Original Screenplay Oscar; and the black humour that bewitched audiences in Killing Eve and now takes riotous centre-stage in Saltburn, the second feature film she has both written and directed.

After the success of her recent projects, Fennell was inundated with offers to create similar, women-led scripts, but she wanted to explore uncharted terrain – to turn her attention to men, and to a different genre. While Promising Young Woman, led by Carey Mulligan, was an alternative take on the revenge thriller, in Saltburn Fennell is stretching the boundaries of the British gothic country-house mystery. At the film’s centre is Oliver (played by The Banshees of Inisherin star Barry Keoghan), an awkward 18-year-old from a troubled, working-class Merseyside family who wins a scholarship to Oxford University in 2006. Like everyone on campus, he is beguiled by the handsome, louche aristocrat Felix Catton, winningly portrayed by Euphoria’s Jacob Elordi. Felix takes a shine to Oliver and, when term ends, invites him to spend his summer holidays at the Catton family pile, the titular Saltburn. So far, so Brideshead Revisited – a source of inspiration that Fennell acknowledges early on, in a line from Felix. But this story’s summer, in all its sun-soaked, hedonistic and increasingly sinister glory, unfolds in a rather different fashion, as do Oliver’s relationships with his host family. The cast is superlative: Conversations with Friends’ Alison Oliver plays Felix’s provocative and damaged sister Venetia, Richard E Grant their distracted father and Rosamund Pike their beautiful, bohemian and mostly appalling ex-model mother. (The latter performance steals the show: when we first meet Pike’s character, she welcomes Oliver and his difficult background with eager fascination, complimenting his looks with the line: “I have a complete horror of ugliness. Always have. I was born with it.”) Elsewhere, Mulligan reappears, in a superb comic turn as a house guest who won’t leave.

Fennell has also played with genre expectations: this is a period drama, but set in the Noughties. Thanks to a note-perfect soundtrack comprising the decade’s big indie-band and pop hits, featuring BlocParty, Arcade Fire and Flo Rida, it thunders along (and has an equal-parts exhilarating and embarrassing Proustian effect on those of us who celebrated school-exam results then). Fennell herself was a fresher at Oxford at the time, so it is a world she remembers intricately. “But also, in the classic Gothic structure – Wuthering Heights, Brideshead –somebody is recalling something major that happened in the past, so I needed some distance to flash back to,” she says. “And wherever you are sitting in time, 15 years back from that point always seems horribly uncool. It’s not historic, it’s not yet retro, and it hasn’t yet come round again in an ironic fashion. It seemed a pleasingly uncomfortable, and funny, place to set the story.”

A self-confessed control freak, Fennell is a fastidious director. Her brief for Saltburn’s location was a house at which nothing had been filmed before, so the audience wouldn’t half-expect Lady Grantham to walk down the stairs. It had to be a property where the entire shoot could take place – no interiors scenes spliced in from studios – to assist the cast in feeling the film’s narrative of all being under one roof for a summer, slowly losing their minds. She oversaw every detail of the hyper-specific paraphernalia that rises to the surface when student life meets extreme privilege: “Of course I insisted we put a green bottle of Wash & Go in a beautiful 14th-century bathroom and an open bag of Haribo on the bed,” she says. “A place as non-real as Saltburn needs to feel real, to be alive.”

But, in part because Fennell herself acts, her relationship with each member of the cast seems the most important aspect of her film-making process. “It is extremely intimate and requires so much trust,” she says. “You rely on each other profoundly, and you’re often under stress, so you want to know that person is going to be able to see it through with you, and go with you. I found exactly that with this cast.” She’s collaborative, but there are certain rules: some comic ad-libbing is allowed, but she is strict about the actors sticking to their lines in dramatic scenes, because improvising in them loses a lot of the tension. “I’ve realised that if someone is finding a scene hard, it’s because the scene is complicated, unpleasant or revealing – and it’s up to me to help get them through.” In these instances, one of her go-to techniques is to “tell them to do shit acting”. Real people aren’t particularly good performers, she points out – it’s often clear what we’re thinking. “So sometimes, to be realistic, brilliant actors need to deliver lines in a way they think of as rubbish and really obvious. Because not everything can be nuanced and neat – true conversation isn’t always laced with subtext.”

She prefers to create scenes and conversations that are “operatic, and sometimes outrageous”. “Being a human is kind of tragic, in the lame sense,” she says. “As a species, we aren’t grandiose, and so I like to bring a bit of Greek tragedy to telling our stories, to heighten them aesthetically, psychologically and physically.” So Fennell is pleased that we seem to be revising critical opinion and reopening the canon to formerly fashionable stylised films that deliver broader-brush drama. She cites Barbie’s recent success, along with that of Yorgos Lanthimos and Sofia Coppola, as helping to turn the tide. “In any field – art, music, film– subtlety is often seen as the only tool you should use if you want to create something truthful,” she says. “But it so happens that I don’t necessarily want things to feel subtle.” At this, I mention a moment in Saltburn involving nudity and a grave that I watched through my fingers. “There are several parts of this film designed to just give you a squeamish kick, that pleasure-revulsion shiver. But actually, that scene feels like the most straightforward to me,” she says, to my surprise. “It’s the most transgressive, but is also an act of desperate grief and love, so seems like something I can really understand.” Delving into the weaker and darker parts of her characters’, her audience’s and her own psyche is a favourite creative exercise. Her view is that we are all monstrous in some way, and that’s fine, so long as we talk about it. “It’s when we aren’t honest about our monstrosities that we are in trouble,” she says. “And I’ve always liked picking that scab.”

In Promising Young Woman, the specific scab she picked was society accepting men taking advantage of women; in Saltburn, it is contemporary attitudes to privilege and desire – material, social, sexual. As the daughter of the high-society jeweller Theo, she is acutely aware of the affluence and advantages of her own background, and is clear-sighted, often critical, when mining aspects of it for storytelling purposes: “I’m as fascinated and horrified by Felix’s world as the next person.” As for desire, the film explores what she sees as our sometimes sadomasochistic relationship with what or whom we want. “And it’s often about power,” she says. “Who’s got it? Who wants it? How do you get it?”

Fennell has quite a lot of it herself these days. She is in enormous demand, from here to Hollywood, but retains a calm focus and a low-key London life with her husband and two young children. Reaching this point has been 15 years in the making, and she seems to have found her rhythm in writing and directing, putting acting to one side – although she did step briefly back in front of the camera for a cameo in Barbie. This was mostly because it was another chance to work with her friend and collaborator Margot Robbie, whose production company Lucky Chap is behind both of her films, and whom she describes as “the most hardworking, exquisite genius”.

Having won an Academy Award for her first-ever screenplay, she is aware of there being a buzz around her second film’s release, and a lot more attention on her – but remains unfazed. “The Oscar was completely mad. But I’m lucky – it all happened in the pandemic, so there were no red carpets,” she says. “I’m not famous, I don’t get stopped in the street or spend nights mingling with ‘the stars’. I hold Eurovision parties at home. My existence is normal, domestic and wonderfully boring.”

Right on cue, Fennell shows me a photo of her daughter peering out through her cot earlier that morning (“Can you imagine waking up to that child’s demon face?”),and we discuss Nigella’s recipe for bread and butter pudding. “She is someone I would get starstruck by if I met her. Same with Wagner from The X Factor, or the Cheeky Girls, whose festive hit I had to put in the film, of course. I’m a tawdry, tawdry person, Charlotte,” she insists, laughing and shrugging as we get up to leave. I’m not convinced. “No, really. When they go high, I go low.” If that’s the case, and Saltburn is the result, then I think a lot of us are going with her.

‘Saltburn’ is in cinemas from 17 November

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.