At the end of a quiet, nondescript street in Paris’s 11th arrondissement is a chipped cobalt-blue door-within-a-door, behind which lies a noisy, modern iteration of a Florentine Renaissance workshop: a vast hangar populated by a busy, six-strong team of mostly young women, not chiselling marble but chain-sawing cardboard. They are working under the spirited supervision of the studio’s ‘master sculptor’ Eva Jospin, who this month brings her extraordinary vision to London with a series of unique sculptures celebrating that most French export, champagne.

The feeling of productivity in the studio is infectious. This makes sense: while Jospin has been experimenting and grafting for 15 years, using card and cotton to create arresting sylvan installations, it is only in the past couple of years that her practice has garnered international attention. The turning point came when, for Dior’s A/W 21 couture show, Maria Grazia Chiuri sent models striding down a gallery lined with a 40-metre-long embroidered landscape designed by Jospin that echoed the exquisite needlework of the collection perfectly. The artist collaborated with the maison a second time for its S/S 23 show, making a series of baroque-inspired, low-lit grottos carved from her signature cardboard.

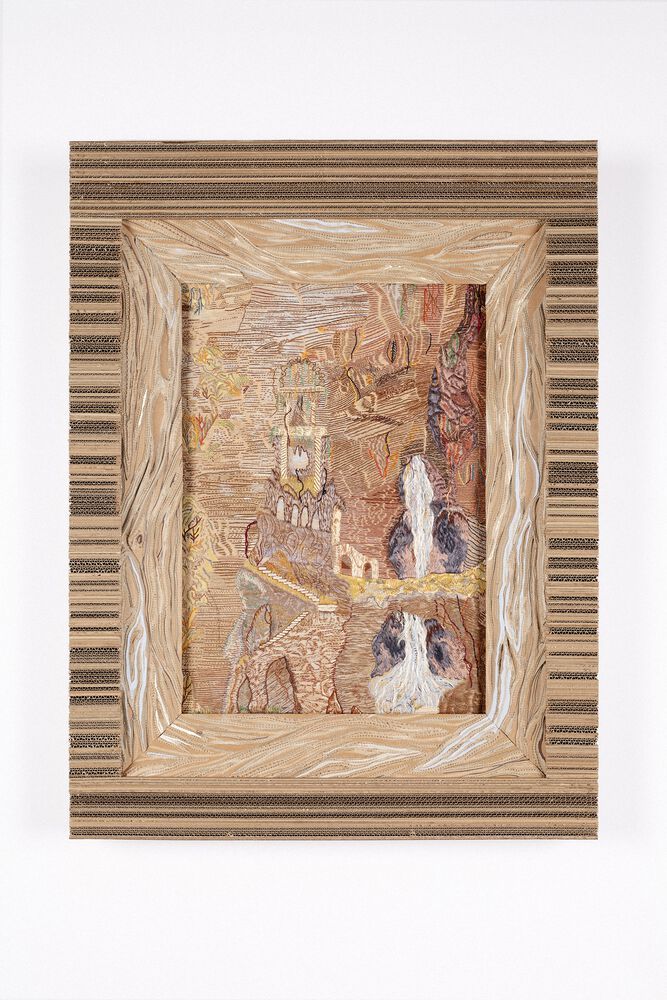

“But I didn’t start with this,” she says, gesturing towards towers of brown pulped-paper creations as we head upstairs to her little office-come-staffroom above the studio. “As a girl, I was fascinated by painting – particularly by the mystery of how to depict real flesh, as skin isn’t a colour…” Later, after a brief detour to study architecture as a route into stage design – “because it’s a real job, so seemed less frightening than just throwing myself into fine art” – she enrolled at École des Beaux-Arts with a determinedly open mind. “I had no style. No purpose, nothing to say,” she declares, throwing her hands in the air. “It took a lot of looking and trying, a long time to build myself as an artist. I was finding my expression.” Happily, she found it – predominantly exploring “how the human hand holds the hand of nature” through motifs such as woodland follies.

Jospin came to the medium of cardboard for both pragmatic and philosophical reasons. As well as being an affordable alternative to traditional, expensive materials – bronze, steel and marble – it is quick to slice into shapes both monumental and microscopic. She compares its corrugated layers, derived from wood, to those found in sedimentary rock – closely connected to the Earth while being a tool available to humans. Now that her work is attracting international acclaim, commissions and thus value, she also appreciates the democratising aspect of her choice of raw product. “I like how there is no inherent economy in art materials – I love thinking about how pieces of paper cut out by Matisse cost the same as a private jet,” she says, smiling. “It’s crazy and I adore that! In art, the simplest gesture can be perfect, it can count – the value doesn’t relate to the cost of production, it relates to the gesture. To opinion.”

This desire to value different perspectives is a common thread throughout Jospin’s work, including this year’s series of sculptures created for Ruinart, which bring the champagne house’s ‘terroir’ to life in miniature. The highlights are a three-dimensional, Escher-like take on Reims Cathedral and a vast vineyard recreation, from subterranean roots to highest-hanging grapes, that visitors to Frieze will be encouraged to walk around and through. “I like people looking at something from all sorts of angles – there is an importance in changing your point of view. We need to keep doing that,” she says. “I don’t want to give a precise fiction. I want to create a scene that advocates growing your own story.”

Jospin’s “own story” is deliberately one that continues to change direction – unpredictability seems to sit well with her. “Things will go wrong, whether you work by yourself or with others,” she says, when I observe how relaxed her studio feels. “I trust my team. Sometimes mistakes come from you and that’s really embarrassing, but you have to deal with them, and then, it makes you more generous with the mistakes of others.” Hence why her dream project would take her to uncharted – and challenging – territory: designing a garden, replete with follies, forests and fountains. It would be her own, but open to the public, because human interaction with her work is the whole point, and the vagaries of horticulture are central to the appeal. “Gardens change, evolve, die or grow. But risk is beautiful,” she says. “When you are creating, there is always a chance something isn’t a good decision, but you have to try.”

‘Promenade(s)’ by Eva Jospin will be exhibited in the Ruinart Art Bar at Frieze London from 11 – 15 October. This feature was originally published in the November 2023 issue of ‘Harper’s Bazaar’

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.