An exhibition looking at how migrants helped turn the UK’s capital into a world fashion centre is an “important lens into London’s Jewish communities”, its lead curator says.

Fashion City, which has opened at the Museum of London Docklands, looks at the impact that those who arrived in Britain had in revolutionising the industry in everything from tailoring to retail.

While acknowledging that the exhibition was opening at a troubling time in the Middle East, Dr Lucie Whitmore explained the capital’s garment business was “a really, really big story for people whose heritage is Jewish London”.

“We really wanted to celebrate the fact that Jewish Londoners have operated in so many different segments of the industry,” she said.

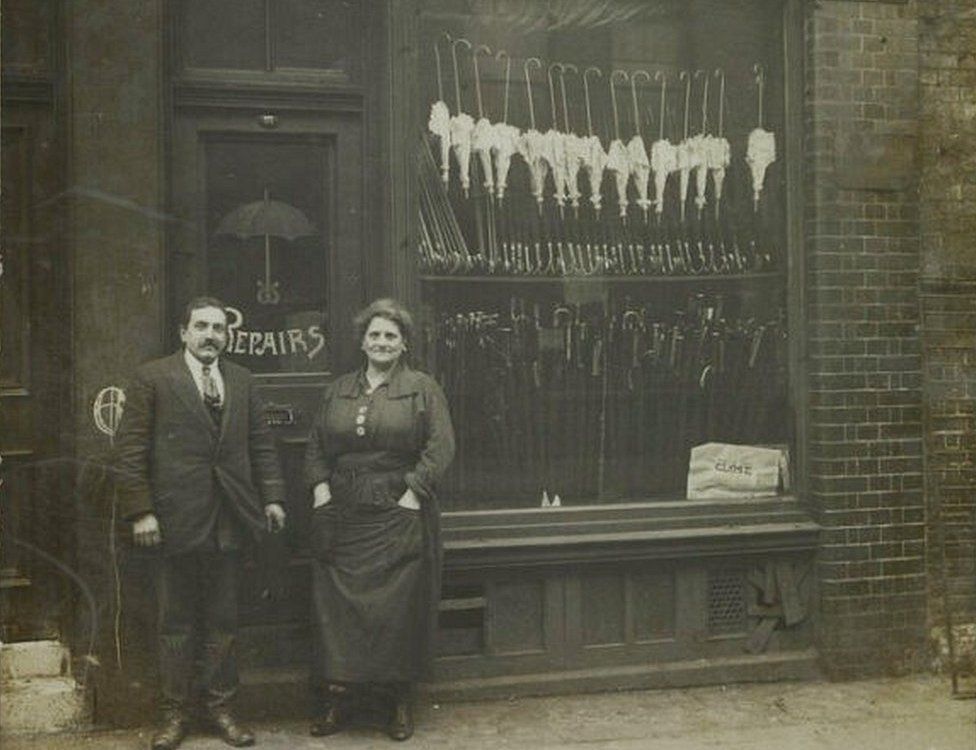

Museum of London

Between the last two decades of the 19th Century and the mid-20th Century, some 200,000 Jewish people arrived in Britain, many with design and clothes-making skills.

“In the exhibition we look at the importance of portable trades, so this idea that you can move with your business, you’ve always got of working and earning a living,” Dr Whitmore explains.

“Sadly, the reality for Jewish people throughout a lot of history is that they had to move for safety, and having a portable skill is very good; you can set up and start making a living for yourself quite quickly.”

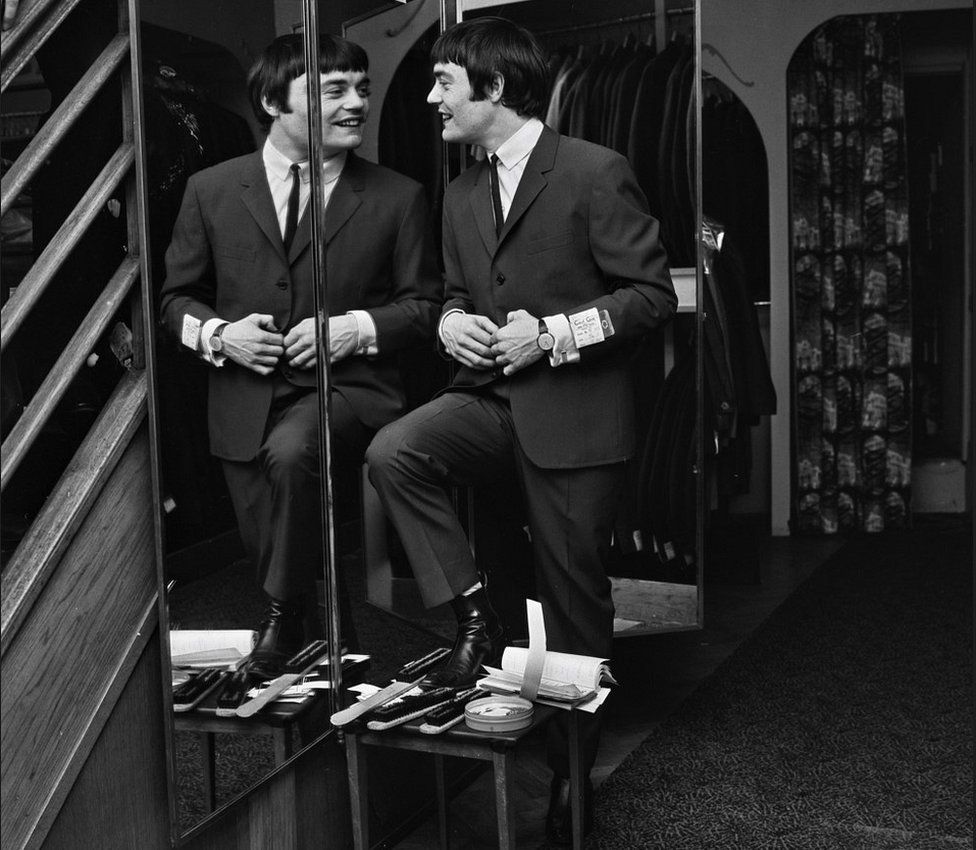

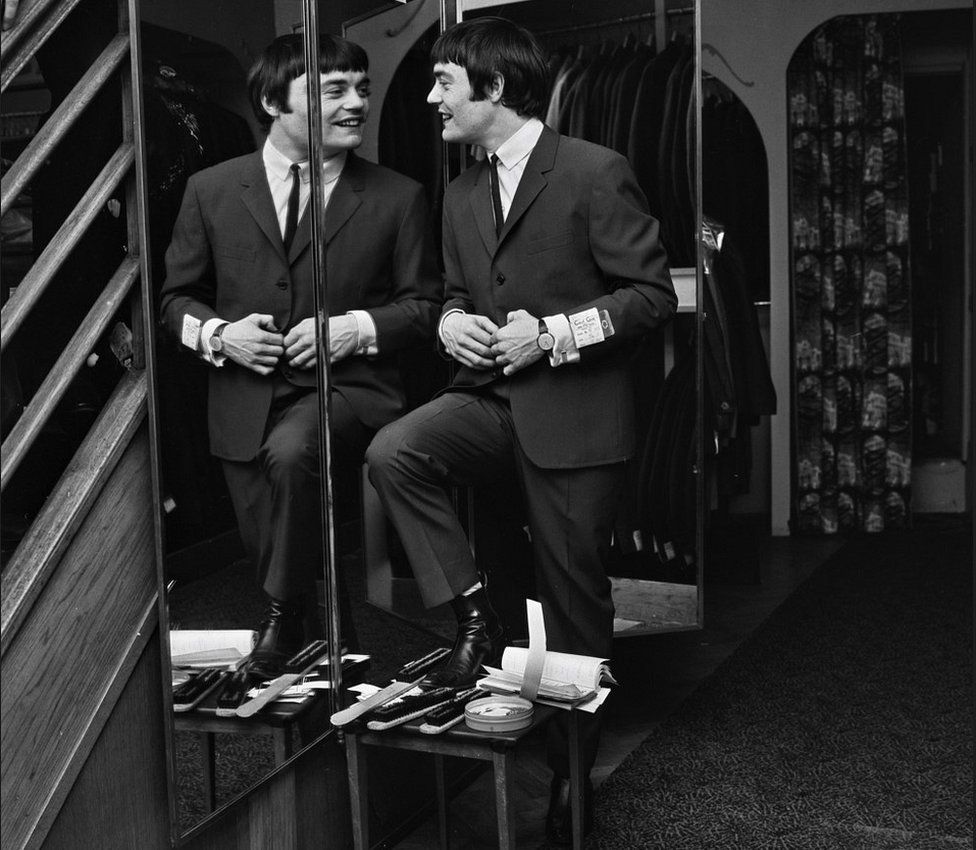

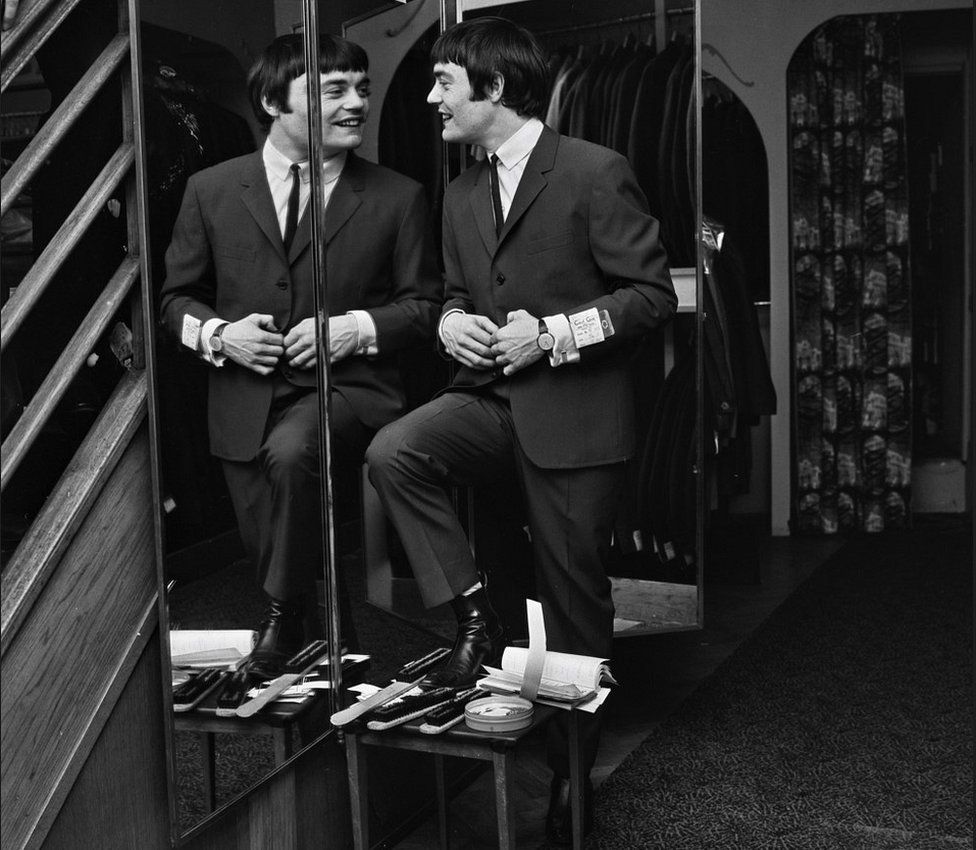

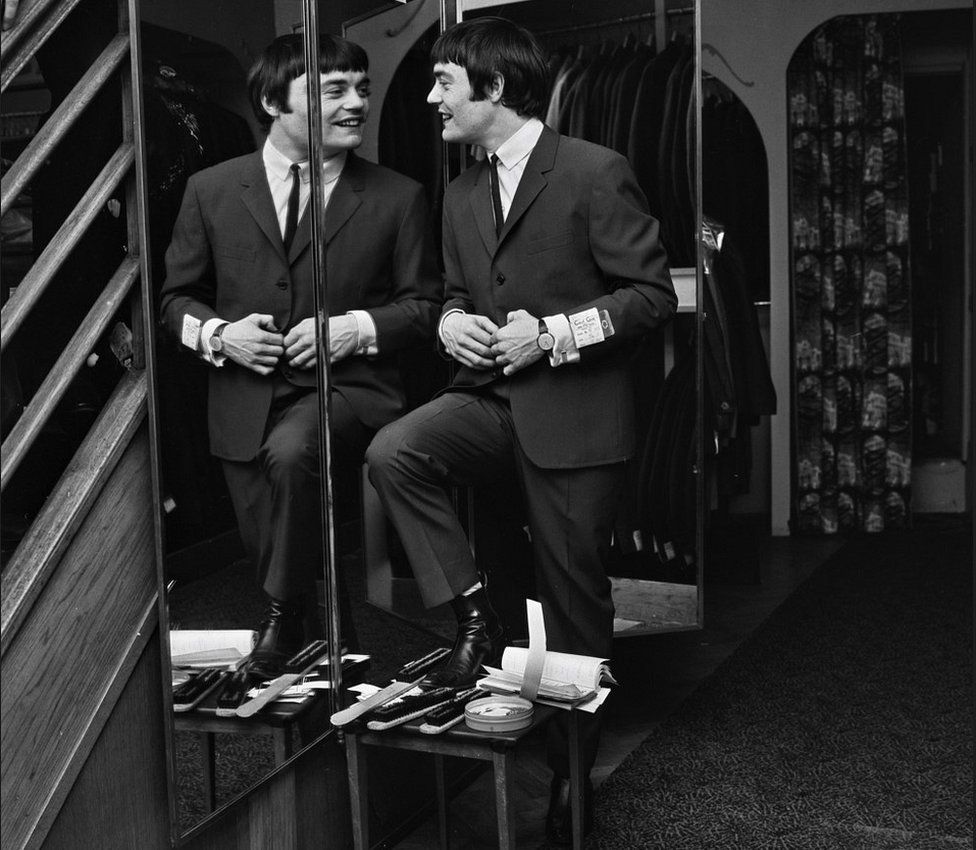

Henry Grant Collection/Museum of London

Some 60% of those who arrived in London ended up working in the fashion industry, with the majority settling in the East End, and the exhibition covers both those who became celebrated for their creations, as well as others who struggled to make a living.

“There are just so many Jewish people working in the tailoring trade in the late 19th and early 20th Century in particular that you can’t look beyond that trade without acknowledging how important those people were in making it,” says Dr Whitmore.

“It was often Jewish designers and retailers and business owners who really innovated and revolutionised the way clothing was made and bought and experienced.”

One of the stories told in the exhibition is that of family-owned leather goods company Molmax, which was started by Dr Whitmore’s great-grandfather in Vienna.

“They came to London in 1938 because they were a Jewish family… they all came separately, but they all came and they re-established their leather goods business.”

The firm specialised in luggage and handbags and would go on to produce items for the likes of Harrods.

“It’s my personal story, it’s so many other people’s personal story and it’s a really important lens on London’s Jewish communities,” she says.

Museum of London

Another part of the display, called Crossing Paths, looks at other migrant communities who have made contributions to London fashion.

It includes the story of Bengali seamstress Anwara Begum who would spend her days working at her sewing machine at home to produce items for both Bengali and Jewish factories in the East End.

“Her daughter speaks of her always sewing into the night in her bedroom while raising four kids at home, so it was very much a part of their everyday life – the noise of the sewing machine going and fabrics everywhere,” explains assistant curator Rhianna Norbert-David, who put together the display.

Evening Standard/Getty Images

As well as being behind innovations in manufacturing, Jewish retailers like Cecil Gee, Chelsea Girl (which became River Island) and Wallis introduced new ways to sell garments and opened stores across the West End, according to Dr Whitmore.

“Cecil Gee changed that experience of going into a store and having clothes out on hangers and in an accessible space, rather than being folded up behind a counter.

“All of these things really changed the way that we shopped and I think for that reason we have to think about Jewish Londoners when we think about London as a fashion centre.”

Getty Images

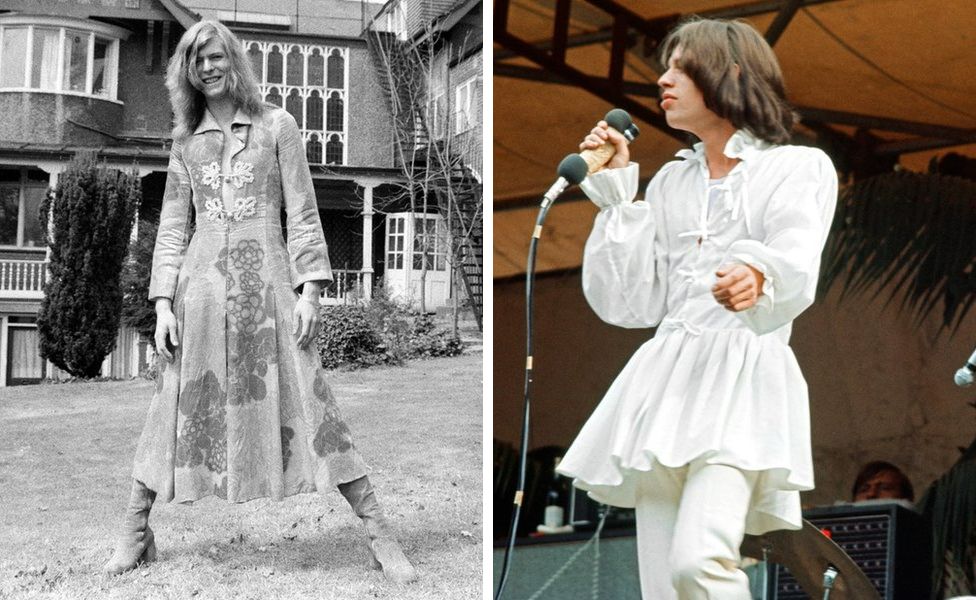

Jewish shop-owners also played their part in turning Carnaby Street into the centre of “swinging London” in the 1960s, with many opening boutiques.

“After the street was brought to life by retailer John Stephen many Jewish retailers followed him and they really changed the look and feel of this area,” says Dr Whitmore.

In order to attract attention, retailers would also organise stunts such as having bands play in shops or women dressing in shop windows. One even employed Welsh crooner Tom Jones and actress Christine Spooner to walk a cheetah up and down the road to get shoppers in.

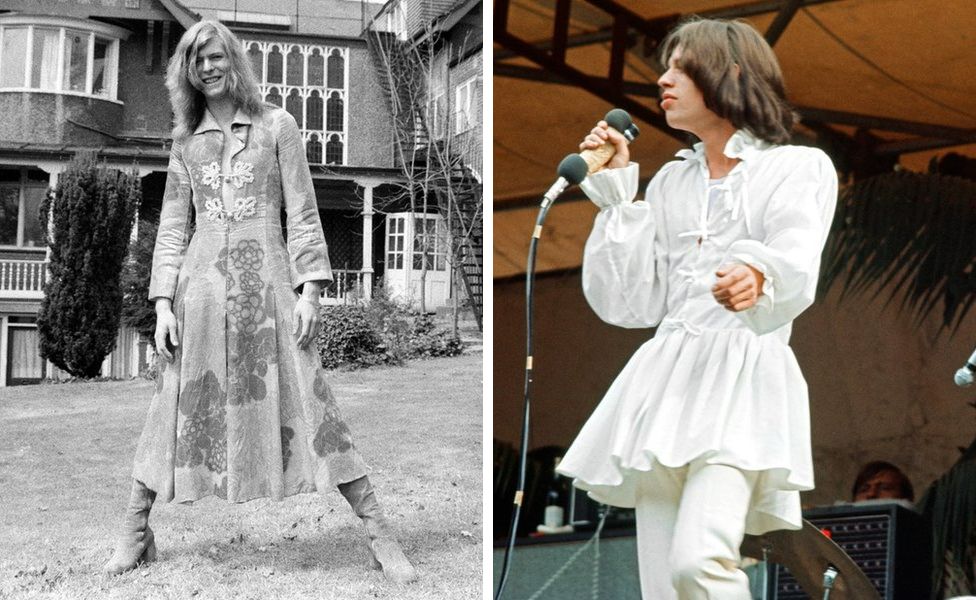

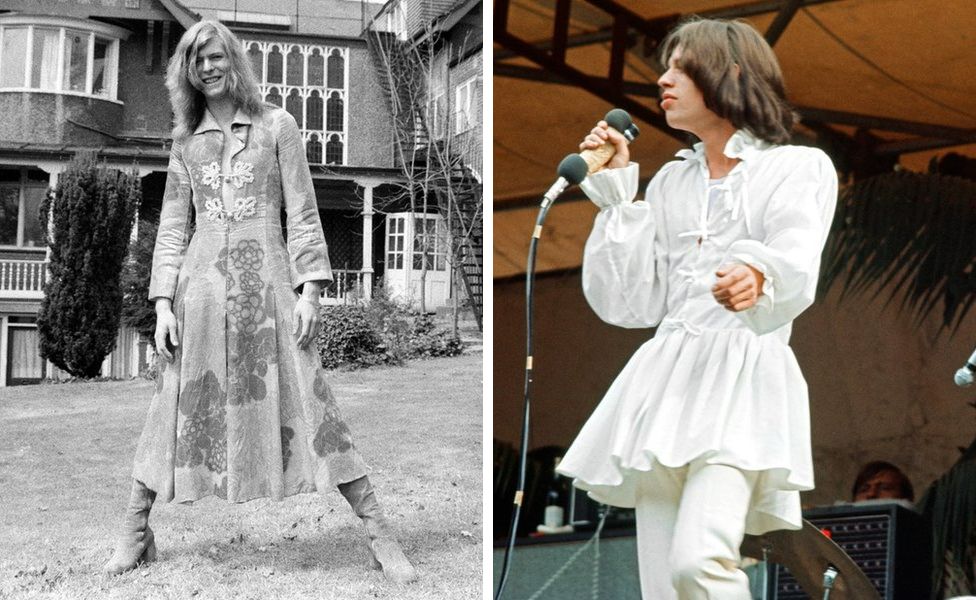

Getty Images

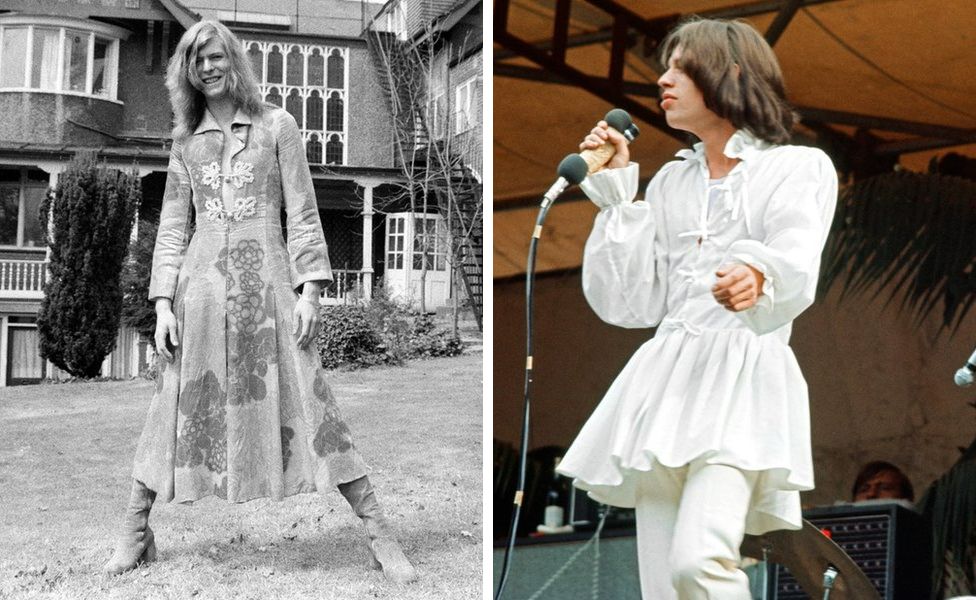

Jewish designers also became part of pop culture, such as Mr Fish who had a shop on Clifford Street in Mayfair and was best known for creating dresses for men due to his belief that trousers were unsuitable clothing for males.

Among those who were fans of his work were music legends Mick Jagger and David Bowie.

“It just shows how much these designers became a part of pop culture,” the curator says.

Museum of London

The exhibition ends with a wedding dress created by Netty Spiegel, who arrived in London alone on the Kindertransport when she was 15. The rest of her family would be murdered in the Holocaust.

She had a dream of becoming a fashion designer and, having first found employment in a fashion firm in Great Portland Street at the age of 16, went on to set up her own couture house, Neymar, where she would create magnificent wedding dresses for clients.

“Netty is incredibly beloved by many generations of Jewish brides today as she dressed them on their special days,” Dr Whitmore says.

“We really wanted to reflect on the fact that the stories in this exhibition are real personal living stories for so many people and they really matter to tell and remember today.”

Fashion City runs at the Museum of London Docklands until 14 April.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk

Related Topics

Related Internet Links

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.