This First Person piece was written by Duke Eatmon, a music columnist in Montreal. For more information about CBC’s First Person stories, please see the FAQ.

It was 1979 and I was driving with my parents from my great-grandmother’s house in Montreal’s eastern Tetraultville neighbourhood back to our digs across the city in Notre-Dame-de-Grâce.

“Now what you hear is not a test, I’m rappin’ to the beat, and me, the groove and my friends are gonna try to move your feet.”

Rapper’s Delight by New Jersey’s Sugarhill Gang came on the radio and my parents and I were in awe. The song is regarded as the first commercially released rap record.

But we weren’t in awe because they were rapping.

Having gone to James Brown concerts at three years old with my parents who were young and hip, we were used to hearing rhythmic talking over music. Brown, Pigmeat Markham, The Last Poets and Isaac Hayes all rapped on some of their records. To rap was old Black American jargon dating back to the 1930’s. In jazz hipster talk, it meant just that, to talk.

What really astonished my parents and me about this funky ditty was that it was 15 minutes long.

It wasn’t two weeks into Grade 4 that almost everyone knew the lyrics word for word. I dove into hip-hop culture with my friends like it was our very own punk movement.

It changed the way we dressed. I wore suede pumas, in whatever colour I could find on trips to New York City, with fat laces. Adidas shell toes were worn with no laces at all. Jeans had to be Levi’s or Lee’s. Lee pinstripe jeans got you a bonus in the fresh department.

We wore Cazal designer glasses, ski masks (I still haven’t figured that out), bomber jackets or sheepskin coats with the matching Yosemite Sam hat, as well as Kangol hats that resembled the lid Sherlock Holmes wore.

My friends Larry, Winston, Jason, Carlise and the entire block of homies on Sherbrooke Street between Benny Avenue and Cavendish Boulevard all had been bitten by the hip-hop bug.

And there was that name, Butcher T. The local legend cut up the records, as we said in hip-hop.

By 1983, Montreal hip-hop heads like me were fiending for one of his mixtapes.

I became obsessed with this mysterious local DJ who was rocking all the parties and was considered the best in Montreal spinning this rap thing.

I finally came face to face with Butcher T in the summer of 1984 at Trenholme Park in NDG. It was the Saturday of the Caribbean Jump Up, now called Carifiesta.

At the end of the parade there was always a party. One of my friends yelled to me, “Butch is on the 1s and 2s!” I ran over to see him perform.

I was astonished. Butch was cutting up the new hit single Human Beat Box by the Disco 3, who would soon change their name to the Fat Boys.

Butch was scratching, cutting, looping and back-tracking the record with the incredible ease and precision that he’d displayed on Club 980 — the Saturday night radio show on CKGM hosted by Michael Williams — and on all those mixtapes that I had been trading my lunch for.

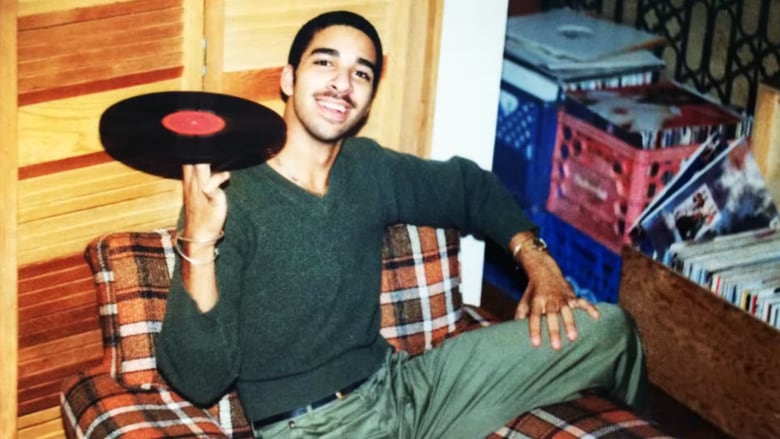

But aside from his mind-blowing turntable tricks, it was his physical appearance that struck me.

He was light-skinned, tall, thin and — aside from his time on the turntables — low key. He looked like an older version of me.

I was 14, he was 20. Butcher T was a superhero I could identify with. He could cut up records with ease and defeat opposing DJs in the name of musical justice.

I’ve long been fascinated by the 1950’s sexual and social revolution called rock ‘n’ roll and the music rebels that led it. And my favourite era of music came out of the counterculture decade of the 1960s. But Woodstock happened two months before I was born.

Though I loved to dance and was one of the funkiest polyester wearing, afro sportin’ eight-year-olds you’ve ever seen, I was a decade too young to be allowed in New York’s Studio 54 or even Montreal’s Lime Light club.

With hip-hop, I had a fashion, political, social, cultural and musical identity that I could call my own.

As hip-hop celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, CBC Montreal is looking into the past, present and future of Quebec’s hip-hop scene, starting with key figures who helped spread the culture across the province and Canada.

CBC Montreal’s conversation about hip-hop in Quebec will continue with a special “Golden Era” edition of The Bridge on Sept 23.

CBC Quebec welcomes your pitches for First Person essays. Please email povquebec@cbc.ca for details.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.