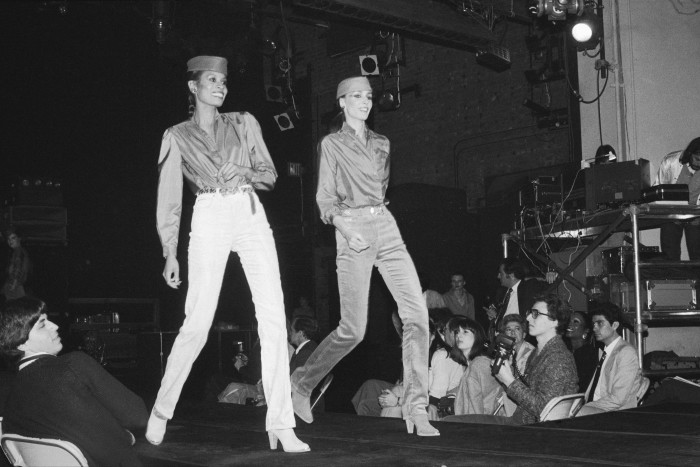

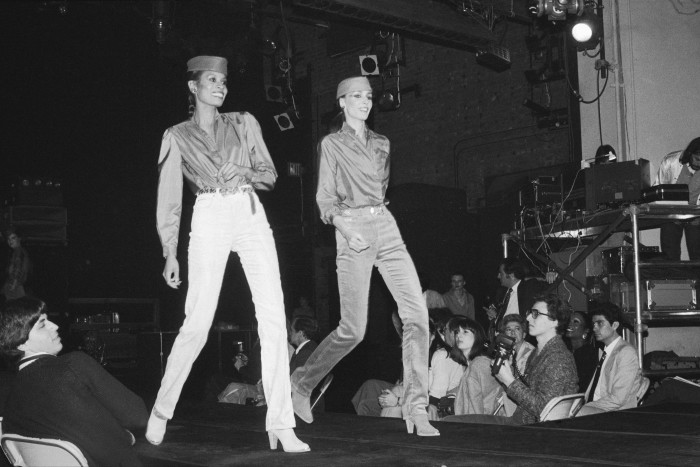

On a wall at the Royal Academy’s Marina Abramović exhibition hangs a series of photos of the Serbian artist in 1974, ingesting antipsychotic drugs for six hours in front of an audience for her celebrated performance piece “Rhythm 2”.

No doubt Abramović intended to unsettle us with a startling scene. Call me superficial, but all I could see were her ludicrously large flares.

As a ’70s child, I have been left with an extreme aversion for trousers with extraneous fabric below the knee. For many of us who lived through the era, flare-fear is real — an involuntary response to an intense moment in fashion history.

The earlier part of the decade, as I remember it, was one of the few periods in which most people wore the same thing: rich, poor, adults, children — everyone wore flares. Even business suits were flared.

Then, towards the end of the 1970s, flares fell suddenly and spectacularly out of fashion, at least in the UK. But why did that happen? After all, they were just a cut.

“Flares fell out of style very quickly,” confirms Caroline Stevenson, programme director of cultural and historical studies at the London College of Fashion. “They had become symbolic of a type of counterculture, and then very quickly the counterculture moved on.”

I put out a call on social media for more recollections of that sudden demise of flares. “I went into a jeans shop in 1978 and was told they didn’t sell them any more,” said one respondent. “They really went out of fashion,” said another. “Only squares wore them.” A third remembered “cousins coming over from the US, maybe ’78/’79, still wearing flares and getting looks in the street. We had to go shopping for straights. And this was Bolton, not some hipster enclave.”

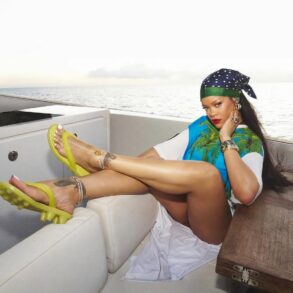

Fast-forward 45 years, and we are somewhere in the middle of a flare revival. And in bad news for my cohort, they are not going away. This time, flares are an expression of laid-back cool for a generation who knows nothing of late-1970s playground taunts and the panicked taking in of seams. Think Y2K-inspired, low-rise boot-cuts often worn with crop tops and a bare midriff.

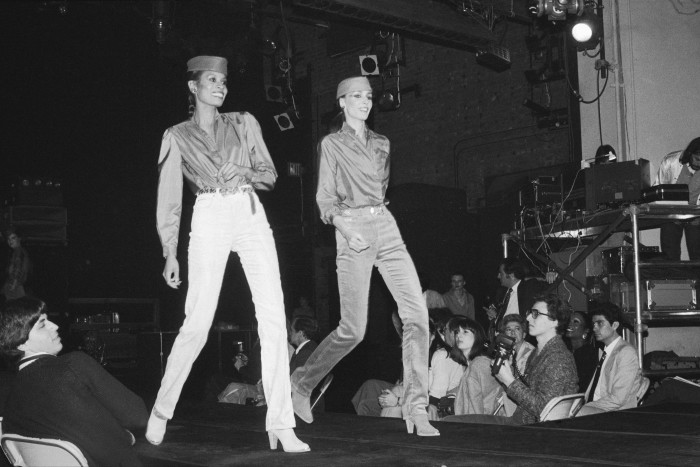

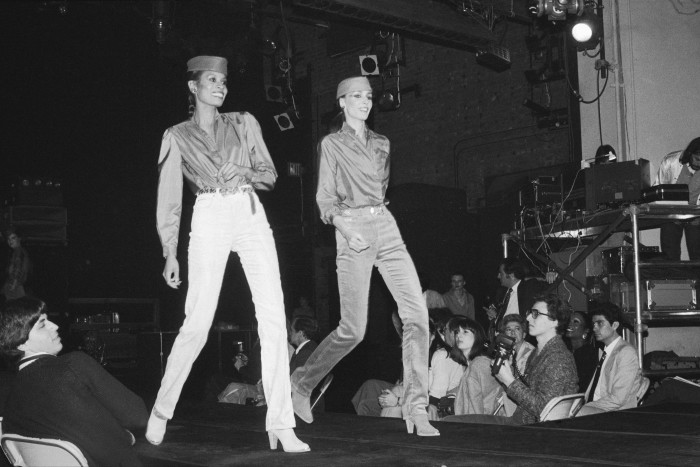

No one wearing this season’s Saint Laurent bell-bottomed twill flares should contemplate going near an escalator. Gucci is offering audacious, high-waisted flared jeans in faded denim, with added, early-1970s details such as massive hems and embroidery. More formal modern flares tend to be elephantine rather than polite boot-cuts. Bella Freud’s trousers are flappy, with sharp cuts that evoke women in stacked heels trailing a cloud of Harmony hairspray.

More of these trouser cuts appeared at the spring/summer 2024 shows, from Sacai, the coveted Japanese luxury brand, with its silken and gauzy flappers, to Tom Ford’s satin and velvet trip hazards. Rita Ora arrived at the Michael Kors show during New York Fashion Week last month wearing billowing, hip-hugging kick-flares that could only be described as cartoonish.

Flare fans claim bell-bottomed hems are flattering. “They elongate your leg and that looks fabulous on anyone,” says Rachel Cameron-Webb, founder of Rock the Jumpsuit, a UK brand whose collection of retro denim suits features what she calls “gentle flares”, with names that evoke 1970s characters real or imagined, such as “Bonnie”, after Bonnie Tyler.

“We definitely sell more flares than straight styles,” says Cameron-Webb, who wears them herself and says her customer base was born in the ’70s and ’80s. “Flares to me say liberation and a free spirit,” she adds, wistfully.

I like to think my spirit is free. So why do I hate flares so much? Perhaps if I understood more about their history, and why they fell out of fashion, I could overcome my aversion.

“Flares came about in the 1960s,” says Stevenson, who explains that the trend started in the US and Europe, with “hippies and young people buying army surplus clothes. The flare look came from sailor trousers and workwear, which was designed to pull over boots . . . That then became symbolic of a counterculture and an anti-war resistance.”

Pop-culture writer and historian Mark Blake pinpoints a particular album cover by design partnership Hipgnosis as his “personal high-water mark” for flares. The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, by UK prog-rockers Genesis, was a wildly successful concept album released in 1974. It has an impenetrable plot based on an hallucinogenic “journey of self-discovery” by a fictional protagonist called Rael, who is depicted on the album sleeve wearing a particularly flappy pair of flares.

“Many years later, I told them [Hipgnosis] those flares really dated the cover,” says Blake, “and they agreed. They told me that they preferred to feature naked figures in their later work so that clothes didn’t date the album covers. Rael’s flares leap out every time I look at that cover.”

According to Stevenson, the flare was wiped out in 1978. “The last real vision of that silhouette was John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever,” she says. After that, a radical generation expressed its politics through the medium of leg widths. “Punks led the way. They were highly politicised, anti-government and highly visceral about their bodies,” she says. “So their silhouette was spare, angular and very close to the body.”

I remember a different moment: in 1977, the first time I saw an advert for Gloria Vanderbilt’s narrow, tube-shaped jeans. By 1979, the American brand claimed to have become the bestselling women’s jeans in the US. Later, it would advertise with a line assuring us that its denim fitted “like the skin on a grape”.

By the 1980s, flares were beyond redemption. In a 1982 episode of the British sitcom The Young Ones, Rik Mayall kicks in a television set in a fury induced by the sight of flares. Everyone sympathised. This was more than fashion’s great churn. Flares became a generational signifier, the uselessness of all that extra fabric embodying the perceived complacency of previous generations. Flares were for the stuffy, the out of touch.

They fell into a 20-year oblivion, only resurfacing again around the millennium. Current flares are different again: less polite, more form-following and feminised than previous iterations.

But whatever shape they take, they are all flared, and they will always be associated with overly lengthy creative projects — at least to me. Like many Gen Xers, I resolved decades ago never to wear them. I would rather go naked.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @financialtimesfashion on Instagram

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.