“I’ve always been a nail girl,” says the chef and cooking instructor Nini Nguyen. Though she couldn’t partake in getting her nails done as much while working daily in kitchens, her new role as a cookbook author has opened up some flexibility.

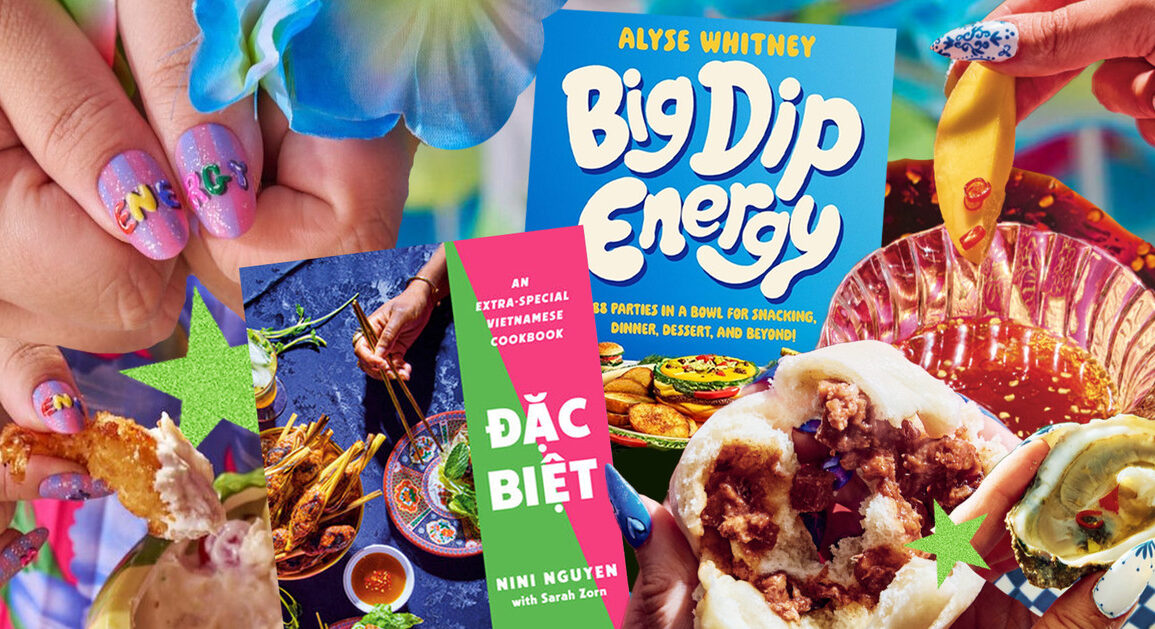

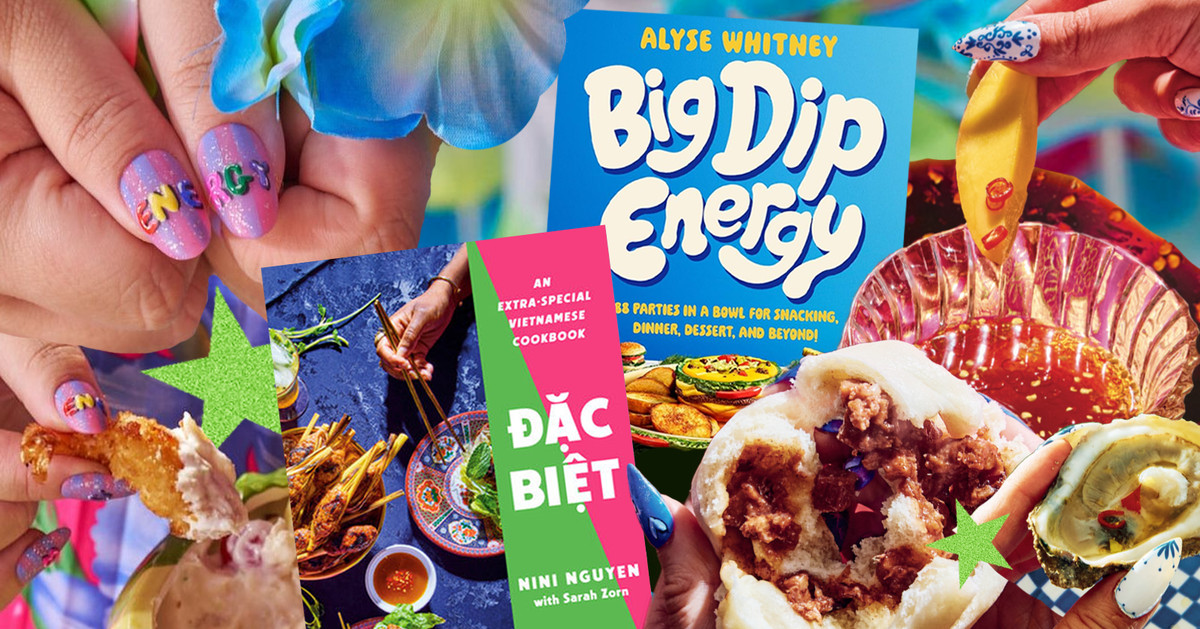

In Đặc Biệt, her debut cookbook, co-written with Sarah Zorn, Nguyen has gone all out with the nails: On one page, you’ll find a pointy blue-and-white manicure that’s designed to look like the melamine dishware her family used when she was growing up; on another, sharp blue tips are adorned with hearts and sparkles. In pictures where Nguyen’s hands pull apart bánh bao, or dip mango into nước mắm đường, the nails also stand out.

Nice-looking nails are a common consideration in food photography. Usually, that means relatively nondescript manicures: on the short side, maybe a fun color. Just like wearing jewelry while cooking, nails can be polarizing for viewers on the grounds of perceived hygiene; that the viewer isn’t actually eating the food they’re seeing doesn’t seem to matter compared to the principle. Accordingly, the implied goal of so many nails in cookbook photos seems to be looking polished and clean, without being overly attention-grabbing.

But a handful of new cookbooks are making nails — painted ones, long ones, over-the-top ones — a priority, so they’re as much a part of the styling as the dishware on which the food is served. To their authors, nails are essential for telling the story.

In Alyse Whitney’s Big Dip Energy, published in April, nail art emphasizes the book’s maximalist, kitschy stylings, which are an extension of Whitney’s whimsical personal style. One manicure features both a bowl of dip and portraits of Whitney’s dogs against a landscape that resembles the backdrop on a Hidden Valley ranch bottle; another spells out the book’s title in puffy, colorful letters. The nails round out the impression of who Whitney is.

Nails also help establish the aesthetic sensibilities of Shannon Martinez’s Vegan Italian Food, out in November. This is made clear beginning with the cover, which features a hand wearing ornate gold rings and sharp, long, red nails. The combination brings to mind the recently dubbed “mob wife” aesthetic; it’s no surprise that the book’s marketing materials reference Scarface as inspiration.

For Nguyen, the nails in Đặc Biệt go beyond visuals to the bigger story she wanted to tell with the book. Đặc Biệt is an ode to the Vietnamese community, especially in Nguyen’s hometown of New Orleans. “My love of nails comes from my family,” she says. Between her mom, aunts, and grandparents, “everybody worked in the nail salons.”

Vietnamese workers, most of them women, make up more than half of the nail salon workforce in the United States, according to a 2018 report from the UCLA Labor Center. Because of that, Nguyen says, “it’s something that I felt like Vietnamese people were kind of ashamed of” — particularly the idea that nail tech was something of a “fallback career.”

With Đặc Biệt, Nguyen wanted to shift that perception: to celebrate nails as one of the Vietnamese community’s contributions to mainstream American culture, and to appreciate the people doing them. In addition to highlighting her family’s work in nail salons, Nguyen thanks her nail techs in the book’s credits. “I think it’s one step closer to making sure we matter,” she says. “I want people to be proud of the things that we do.” (Intricate manicures also feature in Tuệ Nguyen’s forthcoming Vietnamese cookbook Đi Ăn.)

And because the book’s title, Đặc Biệt, refers to that which is fancy, special, or extra, Nguyen wanted intricate details, like nails, to assert the over-the-top vibe. The hands holding the po’ boy-inspired banh mi have maybe the most đặc biệt manicure: pointy and painted with chile peppers, limes, and shrimp. Dangling from the middle fingers are two charms, one shaped like a shrimp and the other like a lime wedge.

This idea of nails as representation is also important to the recipe developer and chef Kia Damon. Damon is working on her debut cookbook, an homage to her home state titled Cooking with Florida Water (Recipes, Stories, and History of the Unsung South). She’s been thinking about what kinds of hands she wants to see in its pages. “So much of this book has to do with the cultural aspects of Florida, which is really Black and really Southern,” Damon says. “I need to have folks with different hands in the photos, but also hands that have their nails done, hands that have the acrylics done.”

For Damon, this inclusion is about creating a cookbook that represents reality. Because as much as critics will have something to say about the cleanliness of cooking with long nails, “your mom or your sister or, outside of gender, your friend who likes to get their nails done is probably still cooking at home,” she says. She sees this resistance to long, colorful nails, particularly in the professional space, as rooted in respectability politics and an anti-femme, misogynistic perspective. From Damon’s point of view, “people wouldn’t be able to relate to opening up a cookbook about Florida and then just seeing nothing but plain nails — that’s not what our world looks like.”

In cookbooks, doing justice to representation involves making considerations like these: details that can seem small on their own, but matter to the people making and buying cookbooks. Whether through the nails or the plates or the backdrops — like Vietnamese newspapers and lacquered wall hangings — on which the plates are set, Nguyen wanted everything to look like a meaningful representation. “It’s not only about Vietnamese food, but I [also] really wanted to depict Vietnamese culture,” she says.

To Nguyen, the nails also spoke to how she wanted the book to feel. In other cookbooks, “the hands look so boring,” she says. “I want my hands to look as happy as my food.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.