“Negative Anthropology” is a new series of essays, translations, and historical texts that center on disability, sexual dissidence, technics, race, and anti-colonialism. Although the materials in the series do not pursue a single shared argument, what joins them is a focus on the gap between forms of insurgent or resistant activity and the models of political representation and visibility that deny the force and legitimacy of such forms. Set within the profound shifts in technical, social, and ecological relations that mark the mutations of capital over the past two centuries, the series borrows its title from a term used by Günther Anders and Ulrich Sonnemann. In their accounts, “negative anthropology” names a reckoning with the human through what it is not: through the distance from the ideals historically posed for and imposed on it, and through the limits and failures of prospects for meaningful social transformation. Departing from that often philosophical work towards questions embedded in social and cultural history, the texts in this series consider the ways that even seemingly radical political frameworks—including those that rely on notions of of community and pride—have often been unable to account either for subjectivities that are not legible within their parameters or for the potent kinds of collectivity and action that start not from any presumed commonality but in the negative space around what gets understood as human in the first place.

—Evan Calder Williams, Contributing Editor

***

Those who grant our conclusions … may ask what we have to say about the woman of color. I know nothing about her.

—Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White MasksLet’s face it. I am a marked woman, but not everybody knows my name.

—Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe”

The “tragic mulatto” has always been a troubling character. A familiar stock figure in twentieth-century cinema and literature, films such as Douglas Sirk’s 1959 The Imitation of Life cemented her typology: she’s a mixed-race Black woman, typically light-skinned or white-passing, who falls victim to the promise of living freely in white society until the revelation of her Black heritage casts her fatally back into social oppression. John Cassavetes’s 1959 Shadows played on the stereotype, and it was the subject of the 2021 Rebecca Hall film Passing, modeled after a novel by Nella Larson. As she has been rendered in culture and particularly in film, the tragic mulatto appears to embody a sort of manic defense against the grief of racialized dispossession. Attempting to circumvent the dehumanization that her (still Black) ethnicity would expose her to, she aims to surpass or suppress her own racialization, only to be punted back across the color line in the end.

There is selfishness, self-hatred, and small-mindedness in this stock character, but also desperation. The tragic mulatto gives the paradoxical impression that she would be better off if only she were less eager to survive the hostile world around her. Crucially, the tragic mulatto’s overt or implied sexuality is often key to her character development, and her desire to be accepted or even to “pass” within white culture is rendered primarily through her potential relationships with white men (as transpires in The Imitation of Life). Because it sits on the fault line of a very long-standing topology of America’s racial and sociopolitical territory, the trope as it has persisted within visual culture is to some extent designed to escape theorization. At a basic level, the tragic mulatto occupies the space of the “color line” itself—of what W. E. B. DuBois alluded to as the “Veil”—and in her contemporary form she personifies the apparent political futility of trying to trouble this color line, both through the voluntaristic assertion of a “post-racial” world and through the facile desire for a ready ethic of “color blindness.” Seen as an allegory not only of self-mischaracterization but of minoritarian political subjectification more broadly, she consolidates the slippery dynamic between contrasting accounts of racialization—between social ontology, on the one hand, and social construction, on the other. As I explore below, the critical impotence that her trope dramatizes and warns of stems, crucially, from her gender position.

Rather than see her as a historical figure, contemporary archetype, or even a “mixed-race” person, in this essay—in part through a reading of Kathleen Collins’s 1982 film Losing Ground—I follow the afterlife of the tragic mulatto as it has continued to influence film and, perhaps more broadly, contemporary culture. In this reading of the trope, the tragic mulatto is not a literal character. She is a cultural encoding that consolidates, in allegorical form, the threat of a specific and acute failure of experimentation in the realm of subjectivity. The tragic mulatto is, in its most essential stereotype, a frivolous and deeply reactionary character, seeking blithely to achieve the same dominant position that will ultimately oppress and disable her. Yet the core of the stereotype operates via a conditioned fear that risks saturating personal encounters with repressive powers of the state and body politic—the idea that knowledge of one’s Blackness will register suddenly with the wrong person at a critical moment, after which “everything will be taken away.”

“Mulatoness” in film and visual culture—an idea that is seldom analyzed in contemporary visual culture at large—offers, I argue, an important counterpoint to Frantz Fanon’s famous account of cinematic representation. Fanon describes his expectation of the degrading representation of the Black man in the cinema: “I wait for me.” Fanon’s Black male filmgoer is caught up in a larger cycle of anticipation and reenactment, which this fraught viewing experience typifies. After a certain point, Fanon argues, in his daily life this spectator self-racializes to such a degree that he in fact conforms fully to the expectations of a colonialist white culture. This is, in Fanon’s understanding, the fatal effect of colonization on Black subjectivity. Fanon’s Black viewer defeatedly performs the racist expectations which he is perceived to essentially embody. As Kara Keeling has articulated this temporal dynamic, Fanon’s account of anticipatory attention to the screen implies a proto-cinematic (or pre-visual) “interval” of time that precedes this encounter with racist cliché through film. Keeling builds on Fanon’s interpretation of the defeatist attitudes he observed among Black communities in Algeria under colonialism. Fanon’s diagnosis is that anti-colonial revolution remains impossible until there is a collective recovery of the isolated “spatiotemporal coordinate” of colonialism’s historical origins. Historicizing the imposition of colonial domination, such that cooperating with its forces becomes a contingent possibility rather than a necessity, was for Fanon a crucial step within anti-colonial activity. Keeling’s reading of the cinematic Fanon suggests that this “coordinate” could perhaps be dissolved or reoriented toward another sort of temporality.

Filmic representation and its racial clichés connect the historical disorientation of colonialism’s origins—which in Fanon’s view underlie performative compliance with racist structures—with the “interval” Keeling analyzes as a potential time of resistance to cinema’s clichés and their “common sense” racial architectures. I take Fanon’s writings (as mediated by Keeling) as a core theoretical bridge between the cinematic and the critical invocations of the tragic mulatto. Through tracing the wider dynamics of which the tragic mulatto is symptomatic, I track the narrative concealment of its dialectical opposite: the forms of cinematic blackout that might enable the novel temporality Keeling alludes to, one which might also open new routes into critical practice that do not, as Darby English writes, amount to an “annexation of private space by rules of social governance.” I position cinematic blackout—not only a literal immersion in darkness but an intervention in plot that severs a prior form of sociality—as the possible unraveling of the tragic mulatto and the possibilities latent in what she has come to suppress.

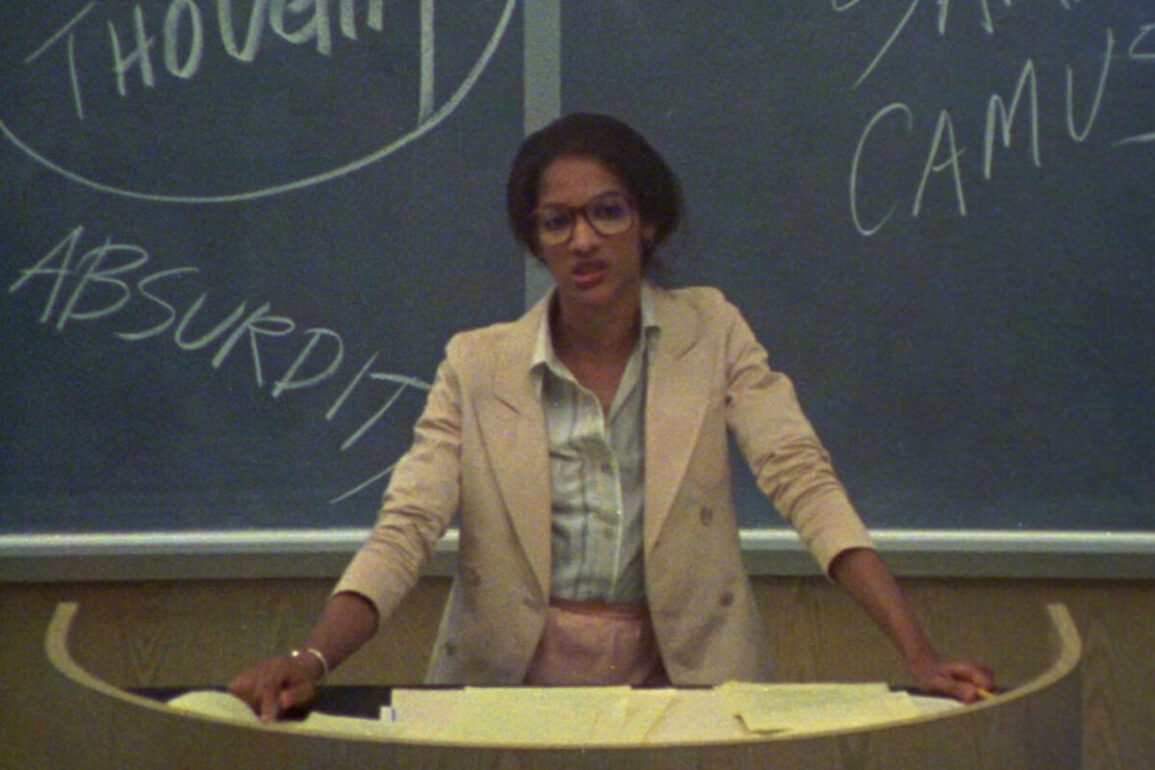

Losing Ground is one particularly illustrative example of how the tragic mulatto trope operates and what else it may withhold. Even on the level of its reception, the 1982 film clearly embodied a crisis in racial categorization. Collins’s stated intention is said to have been to represent the predominantly non-white characters “not as mere race subjects.” The film contains essentially no white characters, featuring an almost exclusively Black and Puerto Rican cast, and as a result is attentive to the racial dynamics that play out between various minority groups within the United States. The film centers around an African-American couple: Sara, a professor of philosophy at a predominantly Black university, and Victor, a painter. The core plot begins when—urged on by Victor’s new creative direction—the pair moves out of the university town where Sara teaches and into a more suburban area that is predominantly Puerto Rican and Spanish speaking. As the film progresses, Sara routinely typecasts herself as rigid and overly rational despite verbal praise from her students that she is “lively” and “passionate.” Sara’s self-characterization is augmented by the perspectives of her husband and mother, both of whom portray her as the stuffy arbiter of order who complements Victor’s spontaneity and chaos. At one crucial moment early in the film, Sara and Victor have a conflict about their recent relocation. Sara appears to object to what she sees as the double standard Victor has now set for her. During a disagreement, she implies that Victor maximizes his own freedom to act and move as he likes, while constraining her and minimizing the value of her own work—by, for example, limiting her access to materials she needs for her research. After some back and forth, Victor brings the argument to a close by saying, “Listen, would you … put this mulatto crisis on hold?” However, a typical American viewer of the film would not likely identify Sara as visibly mixed or biracial, such that this and other characters’ subsequent positioning of Sara as “mulatto” go against physical type. Rather than identify a literal ethnic makeup, they accuse Sara of a particular subject-position.

One of several passing allusions to “mulatto” subjects in the film, this and other “mulatto” designations in Losing Ground intervene at various moments of conflict, always working against the visual expectations we might have as a viewer. “Mulatto” is used to remind one character that another has access to more information (more “standpoints”) than they might have anticipated—but it is also used to downgrade a potential interpersonal conflict to a merely internal one (the “mulatto crisis”). For his part, Victor appears at times preoccupied with the racial origins of the material culture he encounters—foods, aesthetics, and movements are all duly categorized. At one moment valorizing the Latin culture in the couple’s new neighborhood, at another point openly “resenting” it, he leverages ready-to-hand social typologies to account for his own and others’ behaviors. During an argument between a close male friend and his new Puerto Rican lover (with whom he has his affair), he interjects in defense of the male friend to point out that although the man’s father is Spanish, “his mother is a full-blooded, American Black woman.” Victor’s allusion to Sara’s “mulatto crisis” thus emerges against the backdrop of his own race-consciousness and sense of what is or is not “full-blooded” Black. In the context of Victor and Sara’s relationship, “mulatto” invokes racial betrayal and, as such, Victor’s “mulatto crisis” remark acts as a threat to Sara’s moral integrity. The mulatto cliché has a manipulative effect, essentially prompting Sara to remain a structural support for the desires of her husband. Later in the film, Sara agrees to act in the film of one of her students, which—as the student-director indicates—is explicitly built around the theme of the tragic mulatto. As Sara begins to rehearse her part and interact with the other cast members, the film becomes a parallel narrative mirroring her real-life relationship to Victor, whose affair with his Puerto Rican neighbor occurs in spite of his seeming need to limit Sara’s own sexuality. The end of the film-within-a-film coincides with the final shots of Losing Ground—the inner film’s final scene portrays Sara’s character shooting her lover, while Victor, having just walked onto the film set, watches her from behind the film’s director.

While this “mulatto” designation is seldom explicitly invoked in the narrative and mentioned only offhand by various characters, it bears great significance for the ideas Losing Ground puts into play. By the end of the movie, Sara’s violent gesture—performed through the proxy character in which Sara is cast—implies a drastic severance from the expectations Victor has placed on her. Yet her dramatic persona also expresses the culmination of a larger search for what Sara deems an “ecstatic” subjectivity. The closing moment of Losing Ground is intense: Victor is visibly in shock, having run on set just in time to watch the scene play out. The camera cuts abruptly to black directly following this irruption, a blackout that—because it emerges at the dual juncture of the overarching narrative and its film-within-a-film—is a fecund moment. It feels not so much like a cut or an ending as an insistent expulsion of filmic expectation: the body is gone, but flesh remains. This blackout strikes the viewer as the recoil of Sara’s character’s fatal performance. At the same time, it is the expression of a decision to embrace a new rift in subjectivity that will put her outside the representational frames within which she has been enclosed.

Although Collins’s work has drawn attention in recent years as an exemplar of Black independent film, there appears to be no literature that has yet explicitly considered what I understand to be the structuring function of mulatto-ness in the film. Prior scholarship has focused on the film’s portrayal of sexuality in its intellectual female lead but, even when this literature has referred to the film’s mulatto myths and personae, it has not necessarily explicated the film’s internal nuances of racialization. Though it may pass over the mulatto dynamics at work throughout the film, most literature on Losing Ground acknowledges the film as a form of “black independent media that challenges representational comfort zones”—the sort of project that is challenging for Black viewers to “advocat[e] for.” In her essay on the film, L. H. Stallings noted of one of the film’s original screenings:

After the screening, a man asked Kathleen Collins … if she had made the film. When she said yes, he replied, “You’re a traitor to the race,” and stalked away. And still later … talking to one of our better known filmmakers … the director … told me he did not like Losing Ground because it was a negative portrait of a black marriage.

These initial reactions to Collins’s work parallel exactly the tragic mulatto cultural code that emerges within the work and indicate that the filmmaker’s own work was subject to the same sort of suspicion of her implicit subject position as the tragic mulatto trope itself enacts. Her work is seen as a trial that, in effect, puts kinship at risk: she is a “traitor,” supposedly expressing a more general negative sentiment around Black marriage (as opposed to, one might reasonably hazard, marriage itself).

Its narrative importance notwithstanding, the invocation of the tragic mulatto in Losing Ground is highly peculiar given both the trope’s implication of white-adjacency and the near-complete absence of white characters in Collins’s film. As noted above, Sara herself wouldn’t necessarily strike the viewer as bearing the mixed-race background from which the mulatto by definition emerges. Brief scenes featuring her family reveal a bourgeois or artistic background. However, her Black mother’s anecdotes don’t betray any interracial relationships. Scholarship on Collins’s film appears not to have had much to say on this point, referring obliquely to the influence of certain mixed-race actresses on Collin’s directorial work. In its recent rediscovery, Losing Ground has been praised by reviewers for its objectively bold account of the complexity of Black subjectivity—particularly as embodied in its intellectual female lead. Yet even as it is heralded as an exceptional work in the context of the larger politics of representation, the greater significance of the tragic mulatto mythology it brushes up against—an undercurrent that could be easily missed without close attention to particular dialogues and dynamics—still warrants further attention. The subtle invocation of this trope in Losing Ground opens onto a larger discourse about how Black women in America are seen to fit (or not) into the critical discourse around family, race, and society.

Why has this mulatto myth been relatively absent from analyses of film beyond the most literal renditions of the stereotype? Why hasn’t it made its way into writing about Collins’s work? While discourse around the idea of the mulatto does exist—one example being Samira Kawash’s Dislocating the Color Line—the dialogue often centers around ideas of “hybridity,” or creolity. Yet clearly, as in the case of Collins’s film, the tragic mulatto archetype is not necessarily dependent on ethnic type or on the performance of proximity to whiteness. Rather, she is a structuring formula. The tragic mulatto imaginary precisely marks a certain practical failure of the discourse of hybridity in an American context, for it in the end reinforces a presupposed, calculable division between essential types. Rather than assign to the tragic mulatto the role of problematizing the “color line,” we can instead understand her as the negative expression of an internal differentiation of, and impasse within, modern accounts of Blackness. This is a rift that, in our contemporary moment, occurs between, on one hand, Afropessimist, “ontological” accounts of Blackness as social death and, on the other, more psychoanalytically informed accounts such as those that develop out of Fanon, who insists that Blacks have “no ontological resistance in the eyes of the white man.” As I suggest below, the tragic mulatto then is an aborted expression of a different kind of “outside” of racialization than that which is accessible through the colorist mixing of Blackness with the attributes of a more socially dominant subject position. It points toward a different kind of epistemological troubling of the body and what Hortense Spillers calls the “flesh” (discussed below). The inverse of this persona opens toward an alternate mode of sociality—one that undoes the units of measure by which logistical calculations biopolitically govern the Black body.

The sexual typology of the tragic mulatto maps uncannily neatly onto the vision of the “woman of color” whom Fanon characterizes in Black Skin, White Masks, as part of his larger analysis of the impact of colonization on the psychology and self-perception of Black people. In this noted text on the “psychopathology” that emerges as a result of racist encounters with the European colonial context, Fanon remarks that both women of color and men of color are susceptible to the compulsion to use sexuality and intimacy as a means of assimilation into white culture. Yet, crucially, “The Negro is genital,” and in the formations that beset his culture, it appears the male is the one in whom Blackness is done and undone, making him “phobogenic” for white culture. The “woman of color,” we learn, is not quite visible in this picture. Keeling identifies that, for Fanon,

except when legible because she is party to an interracial desire or an appendage to the Native or the Black—as his wife, for instance—the “woman of color” is, in Fanon’s analyses of colonial discourse and its “anomalies of affect,” invisible and unknowable. When she does appear, she does so as, for example, a projection of what might be raped and assaulted in order to harm the Black man or the potential Black nation.

Here, the Black woman is the sexual threshold beyond which Black consciousness is potentially undone.

While there is more to “the story” of the Black than just this bodily aspect, he seems intrinsically male—a masculine-aligned position that Keeling expands on in her account of Black film in The Witch’s Flight (2007). Keeling’s gloss of Fanon implies that his “woman of color” is below the Black man in the sexual hierarchy but morally responsible for securing the Black man’s social integrity amid his racialization. She is black beyond Black—lowest on the rung of the social hierarchy yet unadmitted into the protection of Fanonian postcolonial theory; she cannot even await the appearance of her mangled representation on screen. This Black woman is described as responsible for avoiding the miscegenated sexual relation, but the potential violence that induces this same relation is disavowed (what Keeling construes violently here as being “raped and assaulted in order to harm the Black man or the potential Black nation”). Her own vulnerability to brutality is unregistered. She upholds what Keeling would call the “common sense” of racialization from which she is cast in or out at will, in her position as alternately hyper-visible and invisible and subject to intermittent “mulatto” derision. She is the critical problem—downgraded from cultural legitimacy by her potential to be the sexual object of white society, yet racially constitutive of Blackness whenever the latter is in a state of emergency. This is the Black woman cast as the illegitimate bastard child of a Black critical consciousness.

Fanon, of course, is writing diagnostically rather than affirmatively. What he points to is a fantasy structure; as such, he implicates the tragic mulatto in her capacity as a cultural encoding, rather than in essentialist terms. Of course, one has to note that the tragic mulatto as a literary figure is a US-American notion, whereas Fanon was writing from an African colonial (and, by extension, European), rather than North American, context. However we are addressing the tragic mulatto here as a structuring figure of racialization rather than a literal demographic. Parallel intellectual histories notwithstanding, it is important to note how the tragic mulatto formation has been effectively embedded into this theoretical structure. The tragic mulatto maintains a problematic relationship to Blackness but, most importantly, she encapsulates how the actions of Black women are construed as putting the very coherence of Blackness at risk, as the latter is formed through a Black cultural nationalism. Likewise, the tragic mulatto is caught up in Fanon’s cinematic dilemma, yet her position involves a different mode of visibility on screen than Fanon originally articulates. She embodies the inarticulable zone of indistinction of the “color line,” and this ambiguous paradigm of appearance marks in turn a different temporal quandary as compared to Fanon’s Black male “interval.” The tragic mulatto embodies untimeliness, an out-of-joint position meant to dramatize the political impossibility that haunts attempts to question what Keeling calls the “common sense” of racial categorization. In this allegory, her insights model a perverse (and false) “freedom” from racist discourses—the authentic contestation of which appears to mandate race consciousness of a type that is adequately “kindred” in its gender position. In turn, the cumulative process of “mulatto production” constructs various no-man’s-lands within otherwise emancipatory cinema, film, and visual culture, from which certain kinds of Black female subjectivity must remain absent. While Fanon waits for himself in the cinema, at first blush Fanon’s “woman of color” has nowhere to look for her own image. Losing Ground is radical in how it breaks with this model.

In Losing Ground, the tragic mulatto emerges not, as we’ve seen, due to an actual inclination toward whiteness but initially as a threat to the coherence of the couple and to the family (as set out by Sara’s mother and husband in the film). Additionally, as I argue, the trope personifies a threat to “kinship” in a wider sense. Through the cultural decoding of the tragic mulatto, we recover the problems womanhood and femininity have raised, historically, for Blackness as an object of inquiry—and Black women’s historically fraught position in struggles often oriented around urgent struggles of Black men. Such a framework has often shown itself uncertain of where to place women (or “the feminine” more broadly) in this picture other than as a source of fragility that is a hurdle to liberation and recognition. In “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” her landmark essay on the complex position into which US-American Black women have historically been thrown, Hortense Spillers reprises the ways in which Black women progressively became the conservative scapegoat for the “problems” attributed to Black communities. In conservative diagnoses, the Black US-American woman is positioned as disproportionately influential through the matrilineal influence she retains in a world in which Black men have historically been key targets of incarceration and deprived of political agency. Yet, at the same time, the matrilineality she represents is rejected as pathological. Spillers explains how the Black US-American woman’s construction is also to a certain extent ungendered—“feminine” only insofar as she also disturbs prevailing accounts of gender. Building off her analysis of this sort of debasement of the Black mother, Spillers writes:

This problematizing of gender places her, in my view, out of the traditional symbolics of female gender, and it is our task to make a place for this different social subject. In doing so, we are less interested in joining the ranks of gendered femaleness than gaining the insurgent ground as a female social subject.

The tragic mulatto trope expresses an anxiety around her potential to secure the “kinship” of which Black woman were historically dispossessed, particularly insofar as their reproductive and care labor was expressed outside of immediate family—either through domestic work predominantly outside the community, or more drastically through the erasure of her maternal link to her children under slavery. This problem of reproductive labor partly shaped the Black feminist update of standpoint theory. Standpoint theory has been a key mode of legitimation for women’s—and later specifically also Black women’s—position in socioeconomic structures, lending currency to so-called “lived experiences” as proper political epistemology. Yet Spillers’s account suggests that such “standpoints”—even where they are sensitively tailored to a socioeconomic position—have never been adequate tools to grasp the power-to-name that Black women in America appear to have inherited. The myth of the tragic mulatto, in essence, is a frustration of the “insurgent” potential that Spillers sees as a counter to “joining the ranks of gendered femaleness.” Upon analysis, the tragic mulatto troubles an inherited, impossible responsibility for securing kinship in her attempt to seek out a new kind of subjectivity that would unsettle familial kinship structures. In the original trope, she has necessarily failed to meet this challenge, only reproducing and exacerbating the racial hierarchy to which she is subjected. The potential failure of experimentation with political subjectivity that the tragic mulatto invocation in Losing Ground warns of is, cast in other terms, a failure to fulfill a certain kind of standpoint epistemology, leading to the risk of becoming the “tragic” trope without an adequately “insurgent ground” to occupy after the abandonment of the standpoint. Reclaimed, this potential of the power to name is also a dissolution of a traditional idea of political community as a familial entity.

We can now say that the Black-woman-as-tragic-mulatto as I have defined her here is temporally problematic relative to standpoint theory. Early accounts of standpoint epistemology drew from Marxian theory. In the same manner that the position of the proletariat has been situated in relation to the potential for politically transformative class consciousness, feminist standpoint theory relied on labor models of gender to articulate a more differentiated notion of class consciousness that would render women’s subjective experience expressive of meaningful truths about socioeconomic structures. Important examples of standpoint theory include both Nancy Hartsock’s early version of the framework organized around (white) women’s reproductive labor, and Patricia Hill Collins’s updated version of the theory for Black women. Other versions of “Black” standpoint epistemology effectively use slavery-informed formulations of Black woman’s labor in order to slot them into a Marxist-Hegelian dialectic of recognition that supposedly undergirds the specific mechanics of Black class (or race or gender) consciousness. In relying on an originally Marxian model of class consciousness and proletarian subjectivity to legitimize “embodied knowledge” of women, early forms of standpoint epistemology like Hartsock’s appeared to narrowly circumscribe the sexuality of the women in question; in order to fit into the standpoint framework, women were (heterosexual) maternal subjects, child-bearing reproducers whose care labor was closely linked to exercising their “natural” (straight) sexual function. This clearly didn’t wholly account for queer women, but also notably failed to account for the “queer” labor of Black women who, regardless of sexuality, were often in the position of caring for babies who were not theirs—perhaps even serving as surrogate mothers. Although labor is less significant in Collins’s account, her corrective to the original standpoint theory presents Black women as “outsiders within” in a manner that refers genealogically back to the labor position of Black women as domestic workers in white homes—“outsiders within” who learn the intimate secrets of the family yet are fundamentally outside it.

The tragic mulatto motif, as it has been used to warn against flippant modes of disidentification in film and in culture at large, belies the degree to which standpoints scaffold registers of governance. To rectify the “tragic” diegesis of the mulatto on the trope’s own terms would require restructuring the character’s actions through an adequate standpoint form. That is, the very position that is most “survivable” from within “tragic” plots of racialized constraint are those which can only be epistemically justified through a character’s performance of their own knowability. To be rescued from political suicide in this vein, the tragic mulatto’s clichéd persona needs to morph into a ledger of the film’s implicit social consciousness. Writing from a different pretext than Spillers, Stefano Harney and Fred Moten also offer their own commentary on “standpoints” in their landmark The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. The standpoint’s theoretical architecture sets itself against the fluidity of alignment that emerges from within what Moten and Harney write of as “the hold,” the uncontrollable dehiscence of kin that emerges from the state of having-been-shipped. “What would it mean to struggle against governance, against that which can produce struggle by germinating interests? When governance is understood as the criminalization of being without interests?” Harney and Moten’s imagination of a “new Black studies” goes on to reference an off-gender subject position that exists beyond the enclosures of the political. Their account parallels Spillers’s elucidation of the shifting gender status of the Black woman that routes, ultimately, back to the pre-politicized, generative “flesh” to which she has access by virtue of the historical distortions to which she has been subjected. Spillers writes:

I would make a distinction in this case between “body” and “flesh” and impose that distinction as the central one between captive and liberated subject-positions. In that sense, before the “body” there is the “flesh,” that zero degree of social conceptualization that does not escape concealment under the brush of discourse, or the reflexes of iconography.

As “mother and mother-dispossessed,” the Black woman stands “in the flesh” as harbinger of a potentially different social subject than that which has already been inscribed through the American grammar of racialization and subjectivity. In this vein, Moten and Harney note:

If commodity labor would come to have a standpoint, the standpoint from which one’s own abolition became necessary, then what of those who had already been abolished and remained? … The standpoint of no standpoint, everywhere and nowhere, of never and to come, of thing and nothing. What could such flesh do? Logistics somehow knows that it is not true that we do not yet know what flesh can do. There is a social capacity to instantiate again and again the exhaustion of the standpoint as undercommon ground that logistics knows as unknowable, calculates as an absence that it cannot have but always longs for, that it cannot, but longs, to be or, at least, to be around, to surround.

The power to speak from a subject position, to narrate from a standpoint, is different from what Spillers registers as the power to name. The power to express the deep condition of a structure, and to translate that finding into political terms, is different than finding new language, than moving out of the camp and into the surround. Moten, Harney, and Spillers might see something else in the strange creature we have been tracking, the cliché of the tragic mulatto: a fleshless body. This is her “white” side—a social existence that is pure body, a “feeling” so logistically refined that her life is wholly determined by others’ knowledge or lack of knowledge about her. Her only power comes from what she is able to conceal or suppress in the service of being potentially known as white enough—through an epistemically hyperactive white gaze (and in opposition to her color or background). Her life is a secret, and even once she is exposed, the tragedy is that she remains the opposite of Spillers’s Black woman (“mother and mother-dispossessed”) who stands in the flesh. The “tragic” mulatto has abdicated the place of “mother” in attempting to sever from the community to which she would otherwise be ethnically tied, and yet it is the inevitable and unavoidable possession of the mother—her Black heritage—that casts her out of society. Whereas Spillers’s Black woman lacks a name because she has a power to create it, the tragic mulatto has given away any chance at speaking it.

One analog to the tragic mulatto and her disintegration under the supposed impossibility of a new subjectivity, of a Blackness that exceeds privatized “governance” of the self, is the blackout scene: a cinematic cut marking an indistinct moment that cannot be subsumed into editing. The blackout is not just a refusal or an opacity, but the space that dissolves the ties internal to a film. The blackout’s intervention both disorients the plot and disrupts the excessive politicality of the mulatto’s appearance—her mythical failure to exist outside of the ties she forges between appearance and social recognition. The ambiguous appearance of the mulatto—her classic cinematic mode of appearance—also allegorizes the epistemic surveillance that politics enacts on the Black female body, attempting to decide whether or not it “passes”—if it is a traitor or an ally, a successful, community-shepherding mother or an unsuccessful corruption of kin. The untimeliness that underwrites the myth of the tragic mulatto might be suspended by an account of what Robert Esposito identifies as the “impolitical,” which acknowledges the political effects of the common time in which experimentations of subjectivity take place, but does not reduce these attempts to a political decision, or standpoint.

The blackout is the obverse side of the standpoint, exploding the tragic mulatto’s double bind and turning the anxious prelude of the Fanonian interval of “anticipation” on its head. It brackets the governance that is enacted in and through the name of “kinship,” and it suspends the evental time of film that would see “cuts” as unwanted visual abrasions in the larger schema of continuity editing. The blackout outlines an “impolitical” space that is parallel to and conditions the political: not locked within the historical coordinates of established social imaginaries that cultural habit traverses, in the name of survival, with such logistical precision. The blackout exhausts the position of characterological standpoint, exhausts the epidermal episteme of racialized spectatorship. It needn’t triumphantly discard identity’s strategic utility nor deploy it cynically for survival. Rather, it restructures subjectification by forcing filmic identification to seek its point of suture in the figureless-ness of flesh. The blackout seeks after an abolitionist practice, toward a mode of community that is neither familial nor kindred at its heart. Instead, it stands for a collectivity that forges insurgent genealogies through the names it creates for the unfamiliar.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.