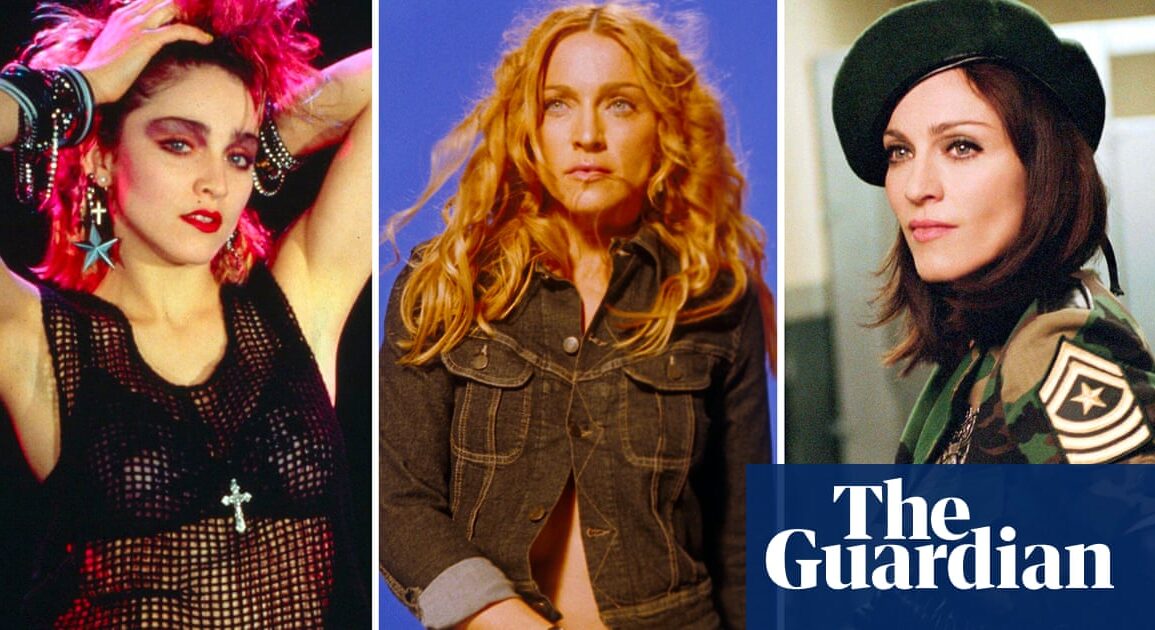

Madonna (1983)

This punchy, scrappy and fantastically frothy record announced Madonna to the world – and the world was never the same. She had made a name for herself through sheer charisma, hustling her way around New York’s post-disco club scene, and she mixes this plucky resolve with simple but effective songwriting. To modern ears, the oingy-boingy synths sound dated and the simple songs feel porous, but it’s a swirling cocktail of enduring sounds and ideas, adjusting the trajectory of pop and laying the groundwork for Madonna’s next 40 years.

Take Borderline, with all its new-romantic melodrama and vocals that swoop from chipmunk-adjacent to breathy desperation, underpinned by straightforward piano chords and a restless, almost vacant cymbal tap: each part of it has a thinness to it but there is an ineffable magic to the sum of those parts. Lucky Star’s twinkling synth arpeggios show up in pop music time and time again (notably referenced by Robyn and Carly Rae Jepsen) – and who but Madonna could take a nursery rhyme and turn it into a whirling dancefloor filler that reverberates through the ages? The punky vocal of I Know It, the sheer commitment to the bit on Holiday, the sultry purr amid Everybody’s playground call to “dance and sing”: Madonna’s charisma holds it all together. Everything she was to become can be found here. Kate Solomon

Like a Virgin (1984)

Like a Virgin was the album that made Madonna the biggest female star in the world. It was sharp, it was provocative, it was fun, it was witty – the cynicism of Material Girl offering a pretty effective skewering of the era’s increasingly blatant aspiration/greed (the word “yuppie” had entered the lexicon between the release of her debut album and Like a Virgin). It was also packed with fantastic songs: four huge hit singles, five if you got the second version, hastily rereleased with the peerless Into the Groove tacked on.

And it was the last album on which Madonna sounded like a product of the environment that birthed her: in its skilful cocktail of post-disco dance music, with a dash of hip-hop (listen to the rhythm of Pretender) and a surprisingly large shot of choppy, angular new wave rock, you could catch the faint scent of the Mudd Club and the Paradise Garage, the bohemian New York milieu that also spawned everyone from Jean-Michel Basquiat to the Beastie Boys to Sonic Youth. By the time of its follow-up, True Blue, everything had changed. She still made fantastic pop records, but everything about Madonna – her messaging, her provocations, her musical shifts – seemed more studied, more obviously calculated, not quite as much fun. Alexis Petridis

True Blue (1986)

An annoying piece of accepted wisdom is that Madonna can’t actually sing very well – that she is a diamond-class pop star in spite of her voice. But while she may not have the exhilarating technical prowess of a Mariah Carey, she is fiercely expressive, and True Blue – her most commercially successful studio album – complicated and deepened that expression. Where previously she had sung girlishly (often knowingly so, as on Material Girl), here she matured, opening up lower chambers of her register and darker cellars in her psyche.

The beseeching, lapel-grabbing tone of Papa Don’t Preach and the trudge of Live to Tell, her first great ballad, are the starkest examples, but Madonna makes even the frothy La Isla Bonita really quite desperate, her yearning urgent and horribly unfulfilled. The doleful vocal tone that marked her out on Borderline in 1983, showing she was much more than a nightclub podium girl is shaken by vibrato, making her sound truly stricken.

There are buoyant moments, such as when the choruses of Open Your Heart and Where’s the Party modulate into major keys, but coming as they do after moody verses the effect is jarring, as if Madonna is insisting she’s having a great time with a rictus grin and wild eyes. As much as I love the “sex” records that were to follow, those husky performances are more obvious than the ones on True Blue, where Madonna, her voice grave, considers the stakes of love with great seriousness. Ben Beaumont-Thomas

Erotica (1992)

What do you do when you’ve conquered the world? On 21 October 1992, Madonna tackled this conundrum as only she would – by publishing a coffee-table book called Sex, which contained explicit photographs of her indulging in activities including toe-sucking, rimming, naked hitchhiking, BDSM, fingering herself while wearing a leather mask and participating in a threesome with two female skinheads, one of whom holds a knife to her crotch.

The ensuing uproar all but drowned out her fifth album, Erotica, a bold leap away from shiny dance-pop and into the grittier realms of hip-hop, house and R&B. Over its 75 minutes, Erotica offers only brief moments of euphoria (imperishable bop Deeper and Deeper, the ballad Rain). There’s an awful lot more anger and pain, both at disappointing boyfriends (Words, Waiting, Bye Bye Baby) and the world in general (Why’s It So Hard, which despite its title isn’t actually one of the smuttier numbers).

One major reason for this dark mood reveals itself in the ponderous ballad In This Life, in which Madonna laments her best friend Martin Burgoyne, taken by Aids aged 23. In 1992, Aids deaths were approaching their peak: an estimated 33,590 Americans lost their lives to the disease that year, with nearly three-quarters of them aged between 25 and 44. If Erotica evokes a world where sex and desire are shadowed by death and fear, that was a daily reality for her gay fans. But there’s also the hope of a new dawn in the two songs in which Madonna celebrates her vagina: Where Life Begins and the brilliant closer Secret Garden, in which she proves that she’ll try anything (at least) once … even jazz. Alex Needham

Ray of Light (1998)

Like a Prayer might nip at its heels, but Ray of Light is Madonna’s best album because it marries pop thrills and heavy drama even more deliciously. Released just before she turned 40, its spirit of epic curiosity twitches and jitters; William Orbit’s trip-hop and trance-inspired textures bring humility and humanity to Madonna’s big pop personality.

This ignites from the album’s opening track, Drowned World/Substitute for Love, full of unsettling ambient winds and a godly vocal sample (from the San Sebastian Strings’ 1969 track Why I Follow the Tigers). Fresh from vocal training for Evita, Madonna sings “I never felt so happy”, but then the beat cuts out. You hear the depth of her lie in her delivery, and this bold vulnerability bristles in the rest of the tracks. It suits her.

after newsletter promotion

Different emotions hit hard. The title track surges with joy; Sky Fits Heaven persuades us to follow our hearts at 140bpm; The Power of Good-bye’s metallic, sequenced synths give glorious gravity to the tale of a breakup. Mer Girl is also a wonderfully weird folk horror finale, about mortality, running away and decay. An LP of strangely epic intimacy, it distils Madonna’s magical powers. Jude Rogers

Music (2000)

Madonna approached the new millennium with her usual spirit of reinvention: “Hey Mr DJ, put a record on.” Ray of Light producer William Orbit was enlisted for early sessions, but his euphoric trance-pop had by then trickled down to lesser stars like Mel C. Madonna needed something new. She found it on a demo by French unknown Mirwais Ahmadzaï. Drafted in for six songs, his micro-chopped grooves (Impressive Instant) and sad robofunk (Nobody’s Perfect) could have only come from the land of Daft Punk and Air. He also had the bold idea to cut the reverb on Madonna’s vocals – central to the airiness of Ray of Light – and the resulting dryness lends Music an unusual intimacy.

It all gels to perfection on Don’t Tell Me, where finger-picked guitar and compressed vocals intertwine with post-Björk strings and a hydraulic hip-hop bassline: cyber-country on the brink of a new millennium. And while Madonna’s politics have been patchy at times, Music contains one of her most enduring explorations of gender in the dreamy What It Feels Like for a Girl. Somehow she managed to follow up the best Madonna album with, perhaps, the best Madonna album. Chal Ravens

American Life (2003)

Madonna’s ninth album was always going to be a hard sell. A “fame sucks” concept record trailed by a lead single featuring a toe-curling rap about soy lattes and Mini Coopers, and presented with the aesthetics of a revolutionary at a time of the Iraq war, it was judged accordingly (the BBC called it “bland and weak”). Clearly in no mood to placate critics, nor fans, Madonna opens American Life with a triptych of songs dissecting the false dawn of the American Dream: that contentious title track, ironic second single Hollywood and the abrasive I’m So Stupid. While her conclusions are often banal – money doesn’t solve everything! – it’s thrilling to hear confusion reign, cogs whirr and the ultimate conclusion that she’s been “stupider than stupid” land like a thud.

But there’s also genuine heart and soul in what follows, all wrapped up in Mirwais’ odd, minimalist fusion of percussive synth rhythms, contorted vocals and cut-up acoustics. The beatific Love Profusion acts as a healing balm to the album’s early flagellation, while the loved-up ballad Nothing Fails is buffeted by a sudden choral burst. Sparkling deep cuts Intervention and X-Static Process continue the mid-album tribute to then-husband Guy Ritchie, the former featuring one of her best choruses, while the latter strips everything back to a tender folk lament.

There are introspective curios at every turn, with Madonna exploring how the death of her mother shaped her on the electro jolts of Mother and Father, upending the conventions of a Bond song on the Freud-heavy Die Another Day and ruminating on ageing on elegiac closer Easy Ride. American Life can be tough going, but it’s the closest we’ve come to seeing the “real” Madonna in all her complicated glory. Michael Cragg

Confessions on a Dance Floor (2005)

Confessions on a Dance Floor plays on a classic trope that has recurred throughout Madonna’s career: never assume she’s out for the count. The follow-up to the misunderstood American Life had a heavy burden on its shoulders: it was the album that would define her as either a multi-generation-defining star or a has-been. It cemented her status as the former, but it is also her last great record, a glorious, neon-hued swan song before her precipitous 2000s downslide. And what a way to go out: Confessions is Madonna’s best dance record, combining the hypnotic stoicism of 1998’s Ray of Light, the skewiff European club throb of 2000’s Music and the clarified, hard-won euphoria of her classic 80s run.

In Madonna terms, Confessions was a relatively minor hit in the US – it won a Grammy and its Abba-sampling lead single, Hung Up, became the most successful dance single of the decade – but for many fans in Europe and Australia, it is the Madonna album, a gargantuan hit that compressed three decades’ worth of dance genres into one electrifying record. The album’s club throb and unashamedly lascivious promotion served as a firm riposte to the idea that a 47-year-old diva should be hanging up her Spandex and stepping into balladworld; its ahistorical approach is, undeniably, the blueprint for hit 2020s dance records such as Dua Lipa’s Future Nostalgia and Lady Gaga’s Chromatica. Those records pale in comparison, of course. Confessions saw Madonna plant Excalibur back in the stone; 20 years on, we’re still waiting for a new heir to pull it out. Shaad D’Souza

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.