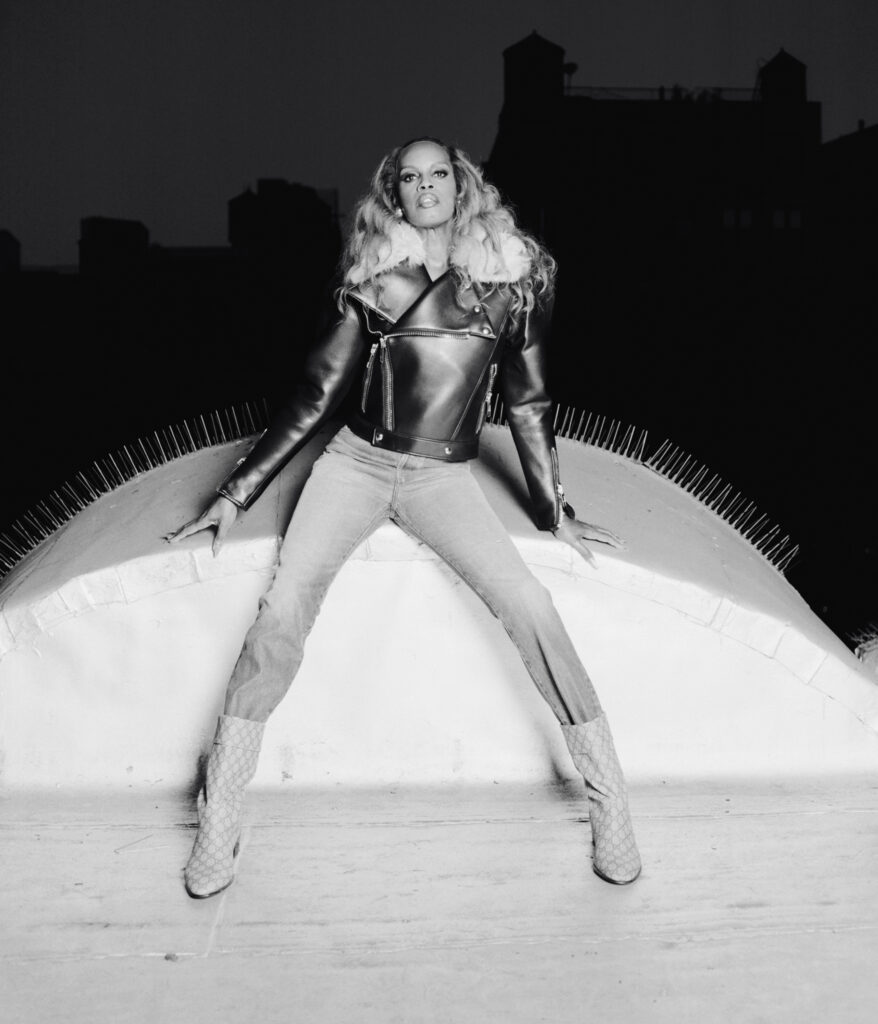

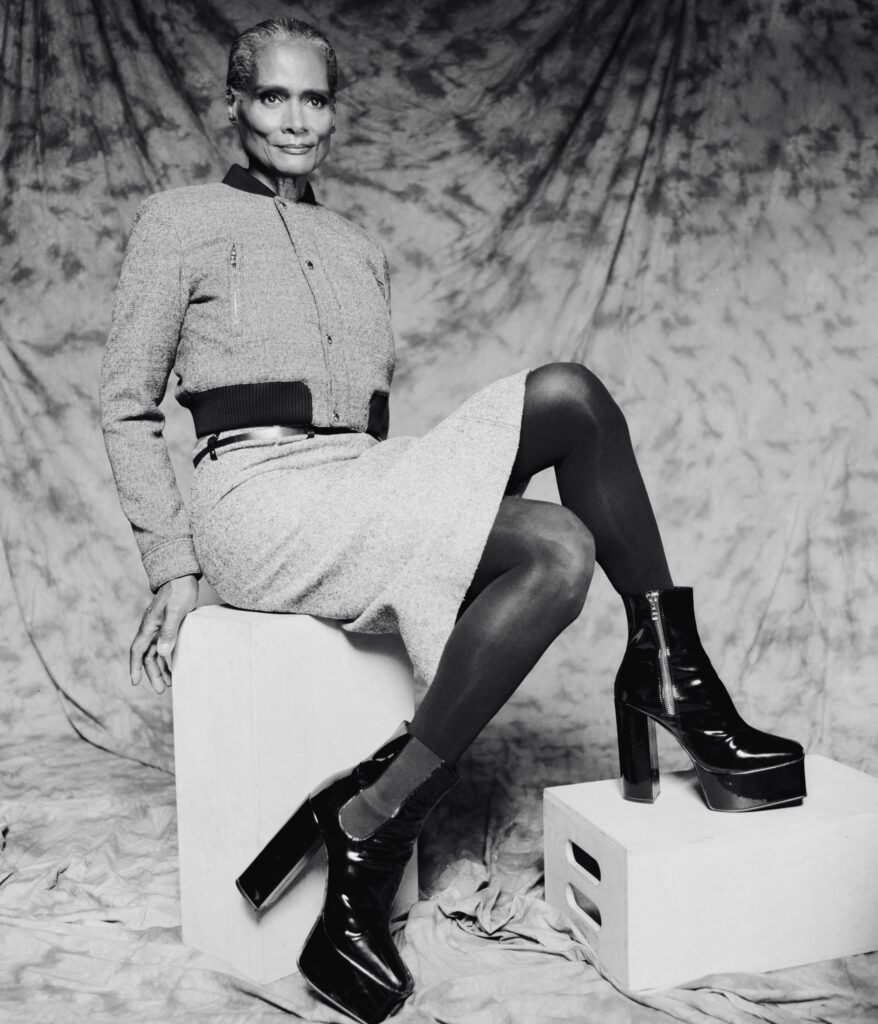

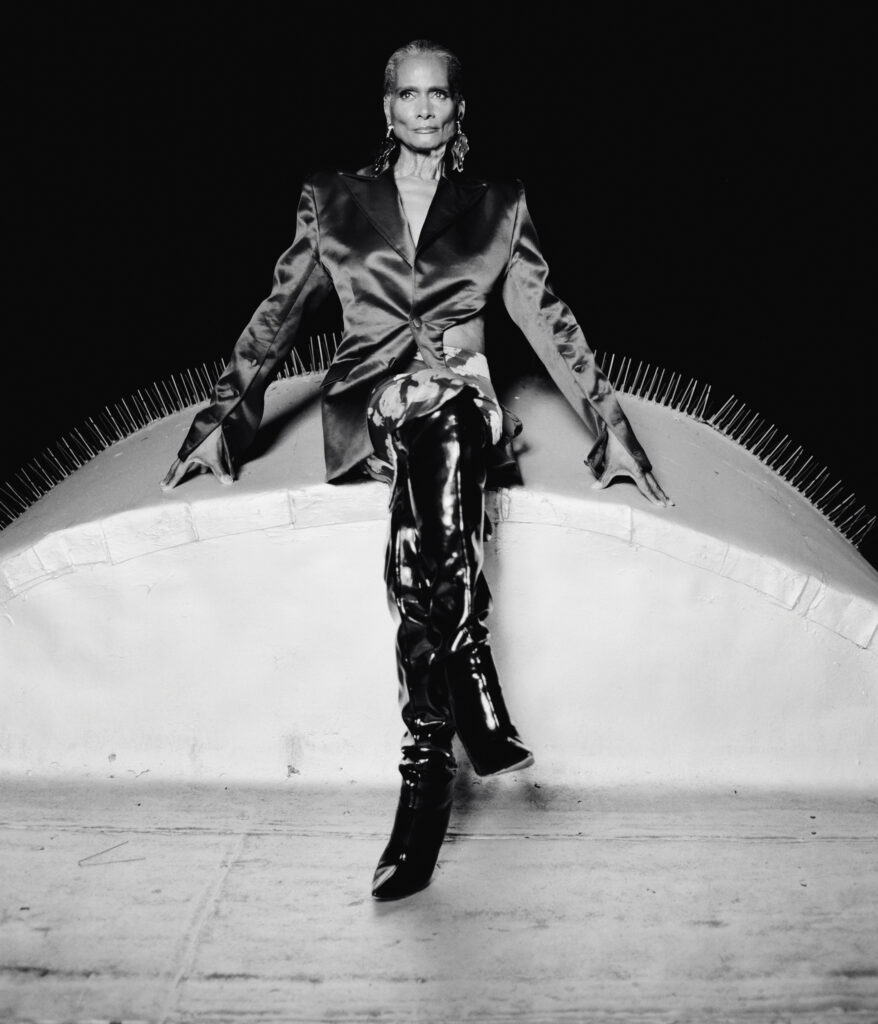

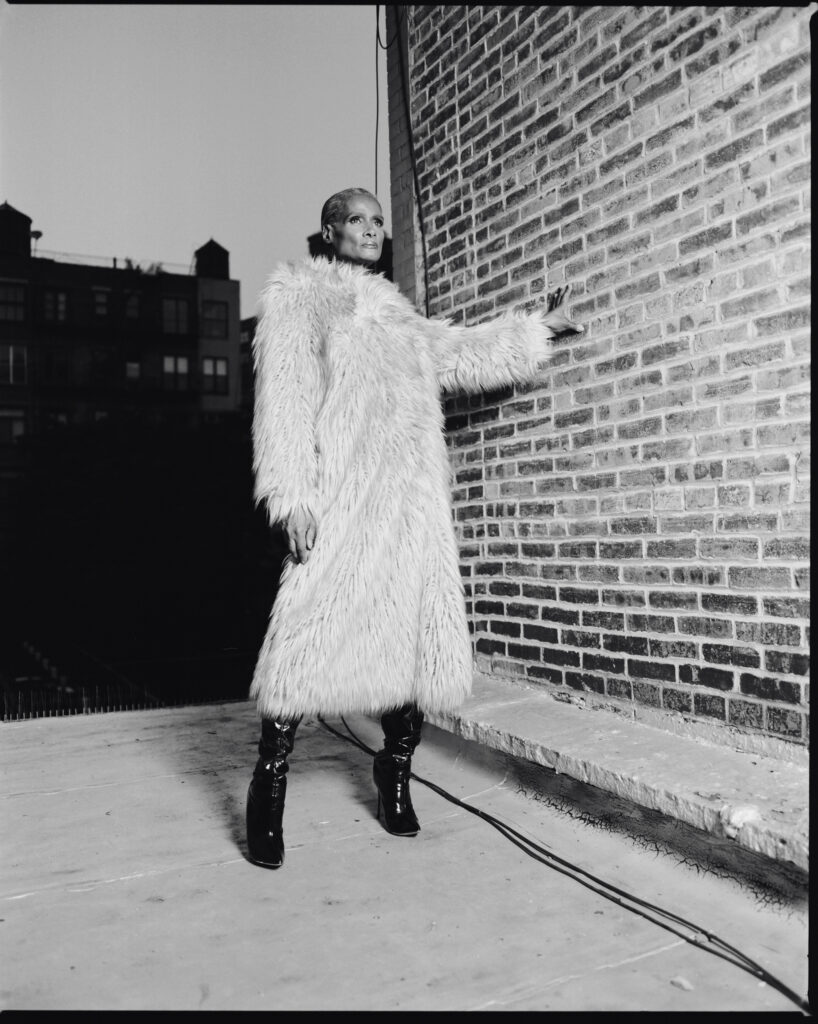

A striking, indescribable sort of beauty—that stop-you-in-your-tracks, “Wow, you should be a model” look—propelled industry legends Tracey “Africa” Norman and Connie Fleming into fashion’s spotlight decades before the business was ready for their otherworldly appeal, allowing them to blaze a trail for generations to follow.

Norman’s baptism by fashion came in collaboration with illustrious image maker Irving Penn, who booked her, unknown and unsigned, for a Vogue Italia shoot. In the years to follow, she landed a coveted gig as the face of a popular Clairol hair dye in 1975, posed for Avon Skincare as well as Ultra Sheen, and even became a house model for Balenciaga. About a decade later, Fleming, who is known more popularly as “Connie Girl”, picked up that baton, photographed by the likes of Steven Meisel, and appeared in magazines like Candy and The Face, which covered the underground downtown scene in which she took refuge.

A chance meeting with Thierry Mugler catapulted her career to new heights. From sashaying down Mugler’s runway in a rhinestone-encrusted cowgirl couture get-up to working for Vivienne Westwood in the early 1990s, Fleming served as a catalyst for the iconic fashion moments that defined an era. These women were scouted and booked for their beauty and their talent—all of it hard-earned, as Norman had to retrain her self-described “bow-legged” walk to be a model. But once they were outed as trans, they were dropped, excommunicated, marked as undesirables, and left to find new industries to work in. It is on their shoulders (and those of others like them) that a generation of women are booked as openly trans models today.

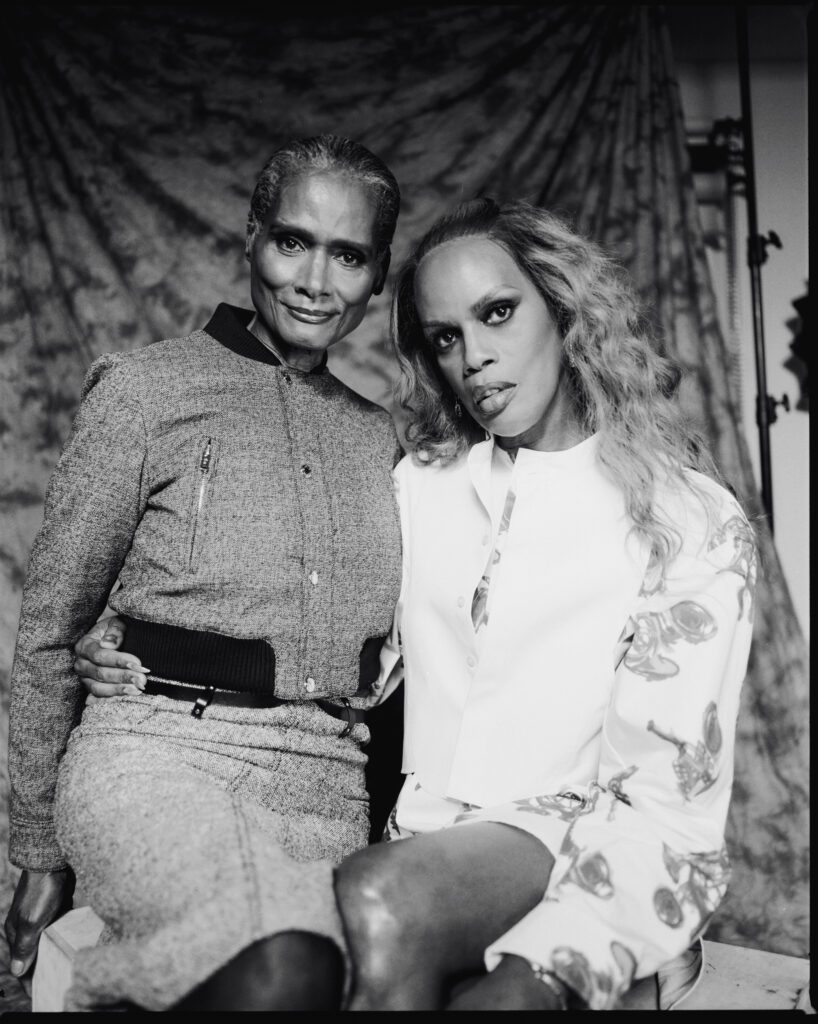

Here, for the first time and in the midst of a renaissance for the pair, Connie Fleming and Tracey Norman appear in an editorial together and discuss their remarkably similar career trajectories as well as what’s next in the industry.

TRACEY “AFRICA” NORMAN: Modeling was something I fell into by chance, but I like to think it was fate. I ran into an old friend of mine in my hometown of Newark, [New Jersey,] after my transition. To his surprise upon seeing me, he thought I was beautiful and suggested that I become a model. He was a top Ford model at the time. So, I started my training in Newark, non-professionally, and then I started doing portraits to learn how to work the structure of my face. From there, I was trained [on] how to walk. That was the genesis of my modeling career. Connie, how about you?

CONNIE FLEMING: My beginnings were on the stages of the Boy Bar. I was trying to save money to go to either Parsons or FIT for fashion illustration, so I found a job at the Antique Boutique. It just so happened that [David] Glamamore, one of my fellow Boy Bar Beauties, had also started to work at the boutique. One night he invited me to the Boy Bar, and I met the [owner]. The East Village at that time was our little community. People began to ask me to model for them and that’s how it started for me, through performance. Performance put me out there to the young up-and-coming designers of the East Village during that time in the 1980s [laughs]. My first shoot was with a photographer for Fad Magazine. That got the ball rolling with other magazines of the moment: PAPER Magazine, Pansy Beat, My Comrade, and Details.

TN: Weren’t you also in Patricia Field’s house when she was in the ball scene back in the ’80s? How did working with such an iconic force in fashion lead to your work as a muse for designers and photographers?

CF: Patricia did this iconic ball in ’88. She used to frequent the Paradise Garage where she met the Xtravaganzas and all the other houses, and they invited her uptown. She went to the Elks Lodge and experienced this vibrant community of creatives who were stuck in the fishbowl of uptown, so she invited them downtown. For Pat, it was about bringing two communities of ballroom together and it just so happened to end up being historic. The judges were Steven Meisel, Betsey Johnson, André Leon Talley, Giorgio di Sant’ Angelo, Mary McFadden, Dianne Brill, and Malcolm McLaren. That was such a pivotal ball that brought the uptown ball scene downtown—allowing the two creative communities to unite. And it was at that very ball, that Steven Meisel saw me and months later asked me to be photographed by him for the Azzedine Alaïa book.

TN: Wow! These spaces and communities that we took refuge in opened so many doors allowing us to blossom and reach heights we didn’t even know were possible for women of color, let alone trans women. I would say things actually really took off for me after my beginnings in Newark. A friend of mine by the name of Al Grundy who worked for Audrey Smaltz discovered that the designers on Seventh Avenue didn’t have professionals to help dress the models, just volunteers. So, she got a group of people together, trained them, and created this business for herself. Al would call me and say, “Go to the Halston show on this day, on this street, at this time. Take your portfolio and tell them that you’re a student at F.I.T. if they give you any trouble.” They let students in at that time but the shows were very private—only buyers, magazine editors, and celebrities could get in. They were doing these shows at their factories, so it was a super tight space. The people like me who came in but weren’t invited would literally be pressed against the wall, while two or three rows of chairs were in front of us —filled with the people who were actually invited. That’s where I got my real modeling lessons, because after all of the excitement around the ambience and people—I was just watching these beautiful women strut. The first thing that I picked up on was that everybody walked with one foot in front of the other. But everybody also had an individual walk. I realized it was the way these women would sway their hips that made them stand out in a garment. After all of that, I would go to Al’s house and he would be relentless. There was this long hallway and he would make me walk up and down, saying “again, again, and again.” It’d be a whole hour of me walking back and forth. Because I’m bow-legged, he had been trying to teach me not to look bow-legged on the runway. I had to learn how to correct myself. I would come home, put my heels on, close my bedroom door where I had a full-length mirror, and practice.

CF: Wow, that’s incredible.

TN: Fast forwarding to the time AL sent me to the Pier Hotel. I noticed that there were models coming up the side street and that there were models coming out of the hotel. They met on the corner and were hugging, saying “hi” and “goodbye.” And then the group that was coming up the street was heading towards the hotel door. I was across the street, observing on Fifth Avenue, and I ran. I literally ran in between cars, the light had just turned green. For some reason, I had no control over my mind, my body, my legs. I was just following the models into the Pier Hotel. The girls were getting on the elevator and I was confused, but I didn’t stop. I got on the elevator with them. I was the last one on the elevator, so that meant when we got to the floor, I was the first one off. When I got out, I turned left and the girls all turned to the right. There were about five girls and I was the sixth. I didn’t know what was going on and this man got out of his chair, came to me, and said, “What agency are you with?” I apologized for being in the wrong room and turned to leave. He called, “Wait, wait a minute. What is your name?” I gave him my name and he asked if I had any pictures on me. I had a color slide, so he took one of the slides. He had me write down my phone number, and my name and thanked me for coming. At the time, I did not know that it was Irving Penn himself.

CF: Oh my God.

TN: They called me two days later and said, “Mr. Penn wanted us to call you to let you know that you got the job.” And I was like, “What job?” He said it was a two-day shoot and I was going to be getting paid $1,500 each day.

CF: You went on your first go-see without knowing!

TN: Yes. My very first one. Two days later, I show up on set, walk in the door, and Mr. Penn approaches me. He introduced himself to me, took my hand, shook it, and said “Welcome.” And then, “Welcome to your new career.”

CF: Wow!

TN: Yes. So, I’m in the dressing room as the models are coming in. I stood up, and introduced myself, and the three girls did not even speak. They just looked, but did not speak to me. Then they carried on with their conversation. Shortly after Peggy Dillard came in. I greeted her, and I recognized her from Vogue. She was the third Black woman to be on the cover. She greeted me back and there was something about Peggy, just this warm feeling, this aura, that I was drawn to. There wasn’t much conversation after that, everybody was busy getting ready. There was a glam team doing my hair and makeup and then they gave me my first garment to put on. They placed all the girls on set, I was sitting on the floor and Peggy was standing behind me. We did the photoshoot, it went well, and he was very pleased with me. He thanked me for coming and I was back the next day.

CF: You were the new girl on the block.

TN: I was. Then, Irving Penn was shooting test shots the next day. On this day we wrapped up shooting, he thanked me for coming once again but then told me to wait a minute, “I want to make a phone call.” I didn’t know who he was calling but he got on the phone and said, “Let me speak to Zoli.” He was referring to the owner of a top modeling agency at the time called Zoli Agency.

CF: I’m familiar with the agency, they were amazing.

TN: He said, “I’m sending a girl to you. She’s the younger version of Beverly Johnson.” They set up a meeting, I went in, and I got signed to Zoli. Following that, the agency started sending me to do catalog work in Florida because I needed more practice in front of the camera. In the meantime, I was losing weight, running in the park, drinking tons of water, and eating healthier. The next thing I know, Zoli is calling me to say I just landed a big job with Clairol—a three-year contract and the option to renew it for a year. So, I did the photo shoot for Clairol and I wound up on the front of the box. With the money I made for Clairol, I left my mother’s house. And I got my first apartment in New York on 70th Street. Not too long after that Essence Magazine called, Susan Taylor asked for me herself because the word was out that there was this new model. My Booker explained to me that Zoli was marketing me as the young Beverly Johnson and that Irving Penn was the person who shot my first series of photos for Italian Vogue.

CF: Yes you have to strike while the iron is hot. Use the momentum to take it to the next level.

TN: Exactly. I thought I was still too green for Essence but the agency pushed me thankfully. They said, “We can’t cancel because Susan Taylor asked for you herself.” I didn’t know who Susan Taylor was, but they said she was the editor and that I needed to see her. So I went to the office, met her, and she was so bubbly. She was excited that we had this first photo shoot and it was going to be an ethnic photo shoot. So I went there, I waited my turn because it was like an assembly line of every Black model in the city coming and going. When it was my turn to have my hair and makeup done, Andre Douglas, the wig maker, came in. Nobody knew it, but he had a wig on his head. He snatched the wig off his head, pulled my hair back, and put his wig on my head. Then they put this heavy steel necklace that covered my entire neck on me. That was my very first Essence shoot and my first time being photographed in an Andre Douglas wig, which was a big deal back then. Tell me a bit more about your journey.

CF: In the early ‘90s, because I had transitioned, everybody was telling Thierry Mugler about this new Black girl. I had just dipped my foot into the modeling world as a performer, but an actual career in modeling was a dream. At that point, I had shot with Steven Meisel and I think I was about to shoot with Steven Klein, so I was on my way. One night while at Susanne Bartsch’s Love Ball, my friend and fellow Mugler-ian named Desmond grabbed me after I got off stage, and he said, “Come with me.” I thought we were going to go to the bar or something like that. We went downstairs to the dressing area and I was going to change out of my look. We turned the corner and there was Thierry Mugler. He was like, “Oh, you’re who they’re talking about.” He recognized me from a shoot I did with Danilo that came out in PAPER Magazine and Danilo showed the photograph to Thierry. I got invited to Paris that first season and everyone thought I was this new African girl. It was only my peers from the East Village and artists from that fashion community who knew of my history as a Boy Bar Beauty drag performer. So, it wasn’t really known and I kind of flew under the radar for the first two seasons. And then my history started to sort of be known but I was so happy in my transition. So happy about feeling good about myself. Not feeling that I was crazy, evil, and everything that they say you are as a trans person. I wasn’t hiding from it, I had an attitude that this was who I am. I wasn’t going to be made to be ashamed of the community that rebuilt me when I was just an injured child. I was always very feminine presenting and in school it was horrifying. I was tortured day in and day out. As a trans person, you only had two choices: working the street or working the stage. I was proud of this community that gave me a chance to grow and gave me the confidence to get on the plane and go to Paris.

(cont.) From there, things started to progress. There was this moment in fashion where drag was pushed as fashion, which it always has been. The play between masculine and feminine. The play of putting on an outfit that would transform you. That is fashion, it’s about transformation, dreams, and aspirations. So then the press started to want me to be a voice for the drag community, and I was like, okay, this was my past, but I am trans and that was sort of put to the side. They wanted to have their narrative and I was put into that narrative. Then, there was a turning point with an article where they didn’t mention drag or my transness, but it was like “There’s a new Black girl, watch out Naomi.” You know how the business is, they pit the Black girls against each other because that’s a way for them to only have one of us. So all of those seeds were being planted. I think it was my fifth or sixth year when I started being labeled as difficult. I came home from Paris one season and my booker was like, “We want to send you on this job. But, you know, you’re difficult.” So that went on.

TN: That’s insane!

CF: I think it was at Vivienne Westwood when a dresser was dressing me, and I was wearing a tiny bikini and I was taped. When I was changing, he saw the tape. Back then it was three to four shows a day. So Desmond, who was also in that show, came backstage and he pulled me aside and he was like, well, they’re saying to Vivienne, “You have a man in your show in women’s clothing.” She turned and said, “There is no such thing at this show.” So then, in between shows, the dresser is standing off to the side and I see him nudging and nodding. I play it off and pretend to look the other way. And there’s this girl sort of going down the line of the models and he keeps on nudging her, kind of like “not that one.” When she finally gets to me, she’s like, “Oh, you’re wearing such a tiny thing,” and tried to ask me about taping. And I was like, “Oh, you mean like at the ballet?” I said, “At the ballet, when you are in a leotard and you don’t have stockings on, you’re doing an arabesque or a six o’clock leg raise, you don’t want anything to come out—so you tape” I turned her question into what happens backstage. And she was like, “Oh, that’s so interesting” and forgot what she was trying to get me to say. The dresser was infuriated. His aim to out me didn’t work. But when I got back, the word was out. I saw the ice closing in around my ankles. I thought, “Okay, it’s over.” It was really “out” out. I was going to be ex-communicated. So I was like, I had a good run, let me find some other avenue. Those were the sort of challenges of being trans and Black at that time in the early ‘90s when they could say anything and make the narrative what they wanted it to be. Also at this time, all the talk shows were trying to target trans people and push this message of, “Oh, this is a trend in fashion.”

(cont.) They painted a picture of these crazy designers pushing this subversive “lifestyle” on the masses. When these talk shows would call, I’d decline and say, “No, that was my past, but I have transitioned.” But in the advertisements and trailers for the upcoming shows, there would be clips of me on the runway. So the media had this mindset of ‘when is this fever dream going to end’ and ‘we have to make it end as soon as possible’ [and] I was caught up in that wave. So that was the adversity I faced. But the racial component, in fashion, I think talent is talent. There have always been people who look beyond race and see talent. I’ve been incredibly lucky to have been taken under the wing of these people who see that race is a part of the beauty of humanity and want to show it. It’s the outside world, the structure of the white, male, cisgender, straight community that wants to impose, control, and make sure that only one version of humanity is seen. Or make sure that there’s something to be able to tear down. But the artistic community wants to champion difference and wants to expose it. There are a lot of creatives battling the power structure presently. We are all foot soldiers in the battle. And I really want to thank you, Tracey, for being a general and leader in this march. It’s not easy and there are so many forces that are hell-bent on making us disappear, but it isn’t possible. Talent, ability, and beauty will always triumph in the end. I am so lucky to be here.

TN: I feel the same way. I’m 70 years old and I’m witnessing some of the success we’ve achieved. Not just the two of us, but seeing our counterparts on television, in film, on the cover of magazines. It’s amazing. I never thought that I would see that.

CF: I never thought I’d see it. I thought everything would be wiped from history. But the march has gone on and it is about being present. It’s about putting your foot in and trying to clear a path, not just for ourselves—but the ones to come.

This story appears in the pages of V144: now available for purchase!

Photography Kendall Bessent

Fashion Altorrin

Makeup Camille Thompson (The Wall Group)

Hair Nelson Vercher

Production Gary Robinson (The Constellation Artists)

Editorial Direction & Casting Czar Van Gaal

Editor Kala Herh

Stylist assistant Sionán Murtagh

Location Public Opinion Studio

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.