SOUTH BEND — As a child, Myron Waddell wanted little more than to hang around South Bend’s hip-hop artists.

He knew the culture stretched far beyond just music, and he had a knack for graphic design. So, his vision was to start a clothing line. His helping of hype would come from T-shirts and jackets adorned with his art, he figured.

But around 2015, when he was in his mid-20s, Waddell started uploading some of his own songs to Soundcloud, a streaming service that gives amateur artists an easy way to share their work widely. He went to shows in South Bend and watched others perform, head-bobbing and admiring from afar but keeping quiet about his own music.

A few years later, he’d battle sickening stage fright and perform his own songs.

He not so shyly called himself Heyzeus.

Waddell, 33, is a leading voice in a South Bend hip-hop scene that’s blossoming 50 years after the art form took root at a Bronx party in the summer of 1973. The year-long celebration of hip-hop’s 50th birthday highlights how the culture in Michiana is cultivated by not only DJs and rappers, but by visual artists, designers, dancers, writers and professors. Established local acts are riding the late-pandemic momentum of renewed live performances while finding new ways to support one another’s art.

Hip-hop shows regularly take place at funky venues like LangLab and The Rocki Button; Waddell got his start at The Garage, an arcade bar that opened in 2019. This year marked the return of the Ethnic Festival, rebranded as Fusion Fest, and the fourth annual Vibes Music Festival, two events that highlight South Bend’s Black creatives.

And this Sunday, an event at Elkhart’s historic Roosevelt Building will celebrate hip-hop’s 50th anniversary by paying homage to acts known across Michiana. Organizer Robert Taylor, who’s worked as a radio host and a DJ for 35 years, said it’s a party that aims to balance nostalgia with appreciation for up-and-coming artists.

More:What is hip-hop? An attempt to define the cultural phenomenon as it celebrates 50 years

Now a favored hip-hop act at local venues, Waddell stands out for his on-stage exuberance, his playful lyrics and his cheeky persona. He subverts the cocky competitive streak in hip-hop and instead calls himself the “cutest rapper alive,” owning his chubby cheeks and his gap-toothed grin.

“I was a very shy, guarded, closed-off person,” said Waddell, a Riley High School graduate. “And I think rapping allowed me to be a lot more assertive, a lot more clear about some of the things that I want to do.”

How hip-hop influences South Bend culture

Hip-hop culture is a big tent.

The South Bend Kroc Center offers hip-hop dance classes. The St. Joseph County Library has studio space for artists to record songs. Multiple local podcasters feature interviews with rappers.

At Indiana University South Bend, criminal justice professor Chloe Robinson teaches a course called “The Criminal Justice Hip-Hop Playlist.” It’s the product of a lifelong love for hip-hop music and years of scholarship, Robinson said.

In the class, Robinson analyzes how hip-hop and the criminal justice system have developed in tandem since the early ‘70s. (For instance: The Drug Enforcement Agency was founded by an executive order in 1973, the same year hip-hop was born.) She teaches students to view the system through the lens of lyrics that convey why people commit crimes and why many Black communities mistrust law enforcement.

When discussing hip-hop’s function in U.S. culture, Robinson alludes to a label used by Chuck D of Public Enemy, a New York hip-hop group known for calling out and criticizing media portrayals of Black communities. Chuck D called hip-hop “the Black CNN.”

“Hip-hop music is often the soundtrack for those who are oppressed …,” Robinson said. “Hip-hop calls for accountability: How can we force institutions to change, especially when they are disenfranchising and marginalizing certain communities?”

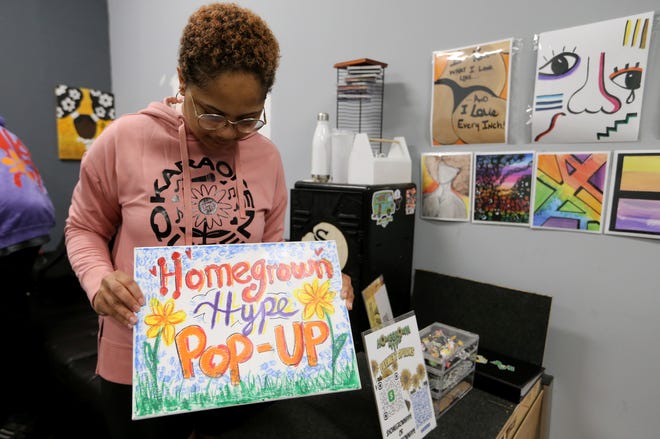

In addition to making music, Waddell and his partners, the performer Nia “Reminisce.X” Okereke and musician Mike “Toast” Roberts, are trying to harness the cultural milieu with their new organization Homegrown Hype. They work to promote artists and connect them with gigs where they can get paid.

In addition to supporting musicians, Homegrown Hype sells vibrantly colored merch designed by Waddell with winning slogans like “South Bend don’t break.” Okereke coaches young performers, sings at gigs and leads karaoke sessions at South Bend Brew Werks and McCormick’s bar.

“The three of us take a lot of pride in South Bend,” Waddell said, “and we want future generations of artists and people not to grow up with that same feeling: ‘Aw, man, I don’t feel seen here. I don’t feel heard here.’”

What Leroy Cobb, 35, heard in the music of younger South Bend rappers made him want to sit down and ask them about it. Although he’s never been a musician, he started The Bruce Leroy Bar Report podcast in 2021. He’s since interviewed dozens of local hip-hop artists about their craft and aims to record a couple of shows each month.

A Clay High School graduate, Cobb was the guy who used to burn songs onto CDs for classmates. He grew up listening to the heavy-hitting gangsta rap of the 90s, but his taste was broadened by R&B tunes and alternative rock.

“I think the beauty of hip-hop is the evolution of accepting new artists,” Cobb said, “and just accepting that it’s never gonna sound the same. As long as these key elements keep coming into play, I think it can go on for another 50 to 100 years.”

Outside at this summer’s Vibes Music Festival, Kristen Givens, who interviews creatives and entrepreneurs on her podcast Inspired By You, talked to a slate of local Black artists spanning generations, including Haven Russell, Marriani Fleming, KEN6TEEN, blkk J and Fye Nixx (pronounced like Phoenix).

Givens said she views the surge in the local scene as a pure expression of hip-hop’s function: “If you’re not invited to the table, you just kind of create your own.”

The rookies and the veterans

Heyzeus is an artist who seems to straddle the city’s recent generations of hip-hop.

He was one of the first local rappers to show Meech Kennedy, who was born in Queens and moved to South Bend in 1996, that South Bend hip-hop had game. Now Kennedy, 28, promotes younger rappers like KEN6TEEN and NLU HenDawg under his brand, Heat Check Studios.

“A lot of people were stuck in the old ways of music — like you need to go to a big city and get a big deal — but now we’ve got the internet,” Kennedy said. “We can put stuff online and showcase from wherever we are. There’s no excuse anymore.”

Others knew Waddell as a subdued teen with a cloudy creative brain.

South Bend native Brian Frazier, 43, went by B-Phraze when he was rapping in the mid-2000s. He said Waddell worked as a sound engineer on Frazier’s first mixtape. Frazier’s family includes musicians Eddie “Million” Miller, 48, and Micki Miller, 37, both of whom have spent time in studios with hip-hop greats but now call South Bend’s west side home.

More:Notre Dame, TSU game an opportunity to introduce HBCUs to South Bend teens

Micki Miller is the youngest of four born to the founders of Faith Apostolic Temple, which opened in 1979. It’s no surprise that her early forays into music were gospel-inspired. But hip-hop infused the efforts of her older brother Jonathan, who led an underground gospel rap group called Flesh Versus Christ.

She played the keys and sang on tracks alongside family members before releasing her first album in 2013. Later efforts like her 2016 album, “Summertime Chi,” earned her praise from DJ Jazzy Jeff, famous for his work with Will Smith as the Fresh Prince, and Questlove, the drummer for the hip-hop band the Roots. Heyzeus features on two songs on the record and has worked with Micki on other projects.

“The hip-hop part was always the foundation with them,” Micki said of her brothers and her cousin. “Even though I was the girl and I listened to R&B and stuff, they made me fall in love with hip-hop. I started off rapping before I was singing because of them.”

Now she owns a sleek music studio that’s part of a cluster of family businesses off Bendix Drive. Eddie Miller runs a gym, Frazier is a videographer with his own business and Jonathan Miller is the pastor of Faith Alive Ministries, the rebranded church.

With state-of-the-art sound equipment and room for small performances, Micki records her own songs and works with other musicians.

She’s seen how South Bend’s live music scene has taken off in the last decade. Inspired to give back, she founded Profound Entertainment Incorporated, a nonprofit devoted to supporting young artists, last year.

Her vision for the organization brings to mind how, more than a decade before he’d be confident enough to swagger across a stage, a shy kid named Myron Waddell flocked to older artists for inspiration.

He left inspired enough to become Heyzeus.

“Every single time that I bring a young kid in my studio,” Micki said, “I like to be able to say, ‘You can do this, too.’”

IF YOU GO

What: A celebration of Michiana hip-hop artists in honor of the 50th anniversary of hip-hop music, hosted by DJ King Robb. With admission at $10 a ticket, the event will feature performances from acts such as Soul Purpose, Sin & Crook, Clik 47, Benji Hardaway, Benzo and many more.

Where: The historic Roosevelt Building, 215 E. Indiana Ave., Elkhart

When: 2 p.m., Sunday, Oct. 1

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.