A woman’s hair is more than something that merely covers her head.

Little girls learn this early. At least I did. I watched my mother color her gray roots over the bathroom sink, pomade her short crop, hide her frizz under a hat. I suffered as she combed out my knotted tresses and sat still as she wove my mane into a French braid.

It seemed that hair held some kind of secret power — that it did more than just make one more attractive or beautiful.

Art historian Elizabeth L. Block noticed this, too. Her fascinating new book, “Beyond Vanity: The History and Power of Hairdressing” (MIT Press, out Tuesday), untangles the importance of hair in women’s lives — emotionally, economically, socially and politically.

Block is a senior editor of the publications and editorial department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She has spent the past 15 years studying portraits of women from the 19th century by American painters like John Singer Sargent and Mary Cassatt.

But while historians have long analyzed the clothing depicted in these paintings, they’ve largely ignored the coiffures.

“Hair always comes last,” Block told The Post. “And I just couldn’t understand why, because women spend so much time on it!”

“Beyond Vanity” focuses on hair practices in the US from about 1865 to 1900, a time of rapid growth, industrialization, the building of railroads and increasing freedoms — which brought enormous changes for women and their manes.

“I read a lot of women’s journals and letters [from the era], and sure, they’re talking about clothes, they’re talking about child-rearing, but they’re talking a lot about hair,” Block said.

“Beyond Vanity” shows that hair had enormous consequences. Letting your hair down in public could get you ostracized from society, but a good head of hair could land you a husband or job. Black women were routinely punished for their hair; former slave Louisa Picquet had her lustrous locks sheared when they provoked the jealousy of the master’s white daughter.

“Women definitely knew the value of their hair,” Block said.

So ladies singed their split ends with candles and smeared egg yolks on their tresses. They spent hours air-drying their hair in the sun (as was recommended).

Women and girls of all classes and races — including in slaves’ quarters — braided and brushed one another’s manes. Some enslaved women donned brightly colored headwraps, to assert their own identity and dignity in the face of such dehumanization.

Eileen Travell

After the Civil War, several changes supercharged the hair industry, said Block: the building of railroads (which made the world “a little bit smaller”), the unprecedented wealth industrialization brought (which led the nouveau riche to throw fancy balls), the invention of the bicycle (which gave women unprecedented freedom and mobility), and the explosion of color print production.

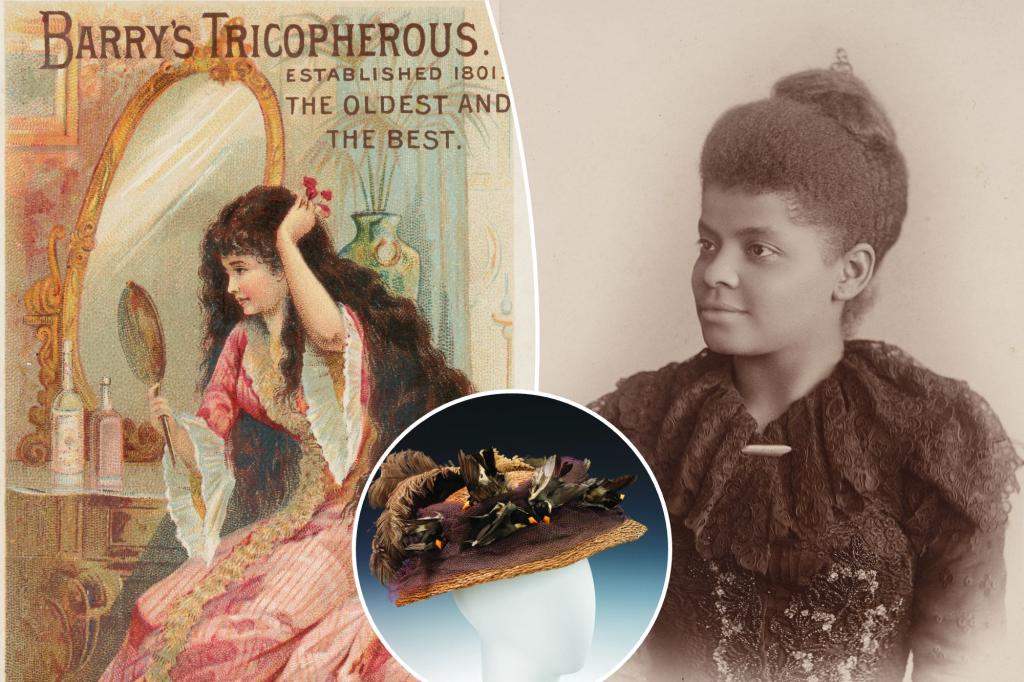

Photos of actresses such as the flame-haired Sandra Bernhardt sparked hair trends.

Gilded Age partygoers spent hours fussing over their outlandish hairdos for galas, which were like stages and breathtakingly covered by the press. (Block mentioned a taxidermied kitten headdress that one socialite, the eccentric Kate Fearing Strong, wore to a Vanderbilt ball.) Advertising flourished, and “hair rooms,” hairdressers, and hair products proliferated the market.

Hair gave women economic and social mobility. Some opened their own salons or worked as independent dressers. One black entrepreneur, Christina Carteaux Bannister, hosted community events and abolitionist gatherings at her hair shops in Boston and Providence, RI, and made enough money to bankroll her husband’s landscape painting career.

Madame C,J. Walker became the first black millionairess with her products made specifically for textured African-American hair.

And hair styles also helped blur class and racial lines. The black journalist Ida B Wells sported the same Gibson Girl updo as her white peers. Shopgirls and socialites donned identical styles. The “New Woman” hastily pinned her hair into a loose bouffant, regardless of status. These new coiffures made working and playing easier — whether scrubbing scalps, riding a bicycle, or swimming at the beach.

“Women were entering public life more, and entering the workplace,” Block said. “So their hairstyles and clothing needed to reflect the need for increased movement.”

Attitudes toward hair have largely relaxed in the past 125 years. Yet hair still has the power to beguile, to frustrate, to provoke, to assert one’s individuality and place in the world.

The global hair care industry is valued at $91.2 billion. But it goes deeper too. In 2022, women in Iran cut their hair in public to protest the death of the young woman Mahsa Amini, after she was arrested by the morality police due to her slipping headscarf.

In the US, Block noted, 24 states have passed the Crown Act, which prohibits schools and workplaces from discriminating against individuals based on the way they wear their hair.

“Hair is a part of all of our lives,” Block said. “It’s a common material, but with uncommon abilities and powers resonant within it.”

“In a lot of ways, this book is about women’s history,” she added. “It’s about women’s lives, and it’s a love letter to hairdressers.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.