Stephen Nissenbaum, in his terrific 1997 history of the holiday season, “The Battle for Christmas,” goes briefly in search of the very first advertisement for Christmas presents — the Yuletide Patient Zero, if you will — and finds an ad urging Americans to buy a good book at the holidays. The year that advertisement ran: 1806, in New England. Within 50 years, this newspaper was running holiday ads for scarves and silk dresses, but a chunk of its Christmas ads were still for books — velvet-covered Bibles, illustrated travelogues of Italy and more. I like to imagine 19th century Americans knew what wise 21st century Americans know: Books are a perfect gift to wrap if you don’t know how to wrap gifts.

That or they understood early on that books were easier to tailor than silk dresses. What follows are the best new books for giving this holiday, organized by the type of people you have on your list. Just remember: Think cleverly designed books. Think keepsakes.

Or just think personal.

“The 500 Hidden Secrets of Chicago,” by former Tribune staffer Lauren Viera, part of an international series of “Hidden” guides, is the savviest of local dives — you don’t need to leave your bungalow to stumble on an undiscovered nook. “Unlikely” art spots, neighborhood “go-tos.” Crisply written, thoughtful. Like TikTok, only smart. “Chicago Skyscrapers 1934-1986: How Technology, Politics, Finance and Race Reshaped the City,” by architect Thomas Leslie, is an ambitious history that’s less the usual roundup of Loop landmarks than an architecture junkie’s dense wandering intriguingly away from downtown. “Midwestern Food: A Chef’s Guide to the Surprising History of a Great American Cuisine,” by Paul Fehribach of Andersonville’s Big Jones, finds room for green bean casserole and hyper-regional dishes — the runza yeast rolls of the Plains, anyone? Still, it’s the odd histories — the latke’s traditional place in Wisconsin fish fries, for one — that sold me.

“Jumpman: The Making and Meaning of Michael Jordan” is no definitive biography, but something intriguing until we get that book: Centered on the Jordan-led Bulls championship in 1991, historian Johnny Smith (a Libertyville native) puts his rise in the context of Chicago racial politics — and a nation eager to believe heroes transcend race. It’s a swift, fascinating read. As is “The Football 100,” a brick of essays on the 100 best players, so chosen by The Athletic. Of course, you get Ditka and Payton, but also the ballad of “Bulldog” Turner and Bronko Nagurski — “If Homer, Vince McMahon and Stan Lee could have collaborated to create a hero, they would have come up with The Bronk.”

A new “Rashid Johnson” career survey from Phaidon — as brisk and complete a history of the Evanston native’s underrated vision as any — is always welcome. Same for “Kerry James Marshall: The Complete Prints,” which collects decades of the longtime Chicagoan’s little-seen woodcuts and engravings — class assignments, Christmas cards, self-portraits — into an alt-history of the artist, one of the country’s most transformative, partly for his reframing of Blackness in art spaces. But this excellent new survey of Chicago sculptor Simone Leigh feels both very overdue and right on time. Leigh, who represented the United States at the 2022 Venice Biennale and landed on Time’s most-influential-people-in-the-world list this year, merges African art and Black American feminism into works that feel architectural, social and timeless. It’s the Chicago art book of the year. Also, since her groundbreaking new traveling show is not scheduled for Chicago — not yet — this may be the closest we get.

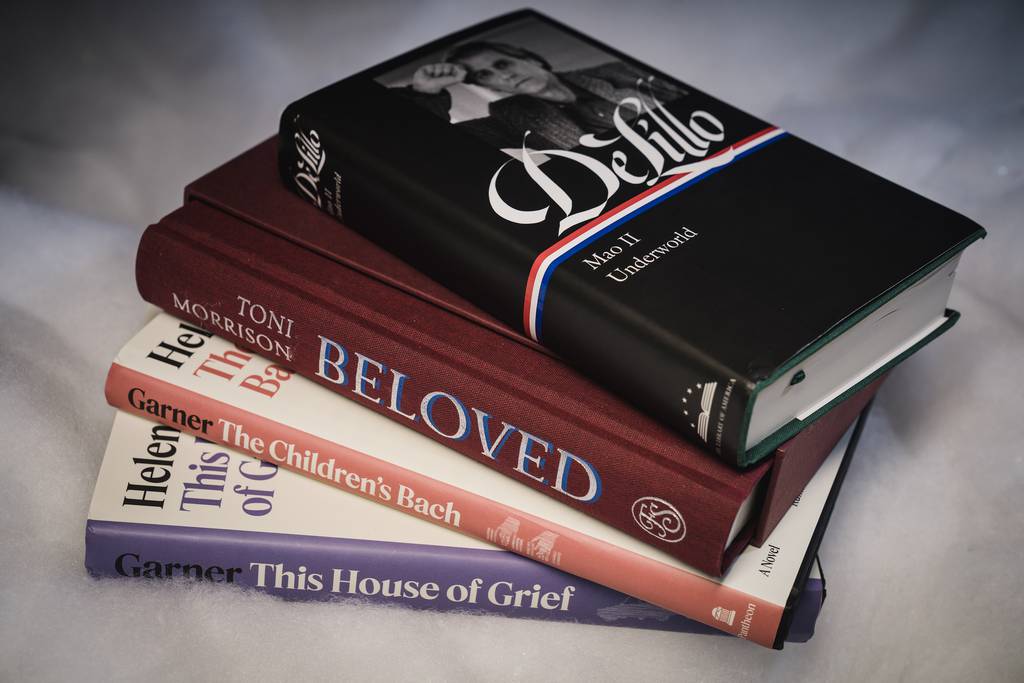

If you’re thinking lovingly-inscribed keepsake, it’s hard to beat Library of America or the U.K.-based Folio Society. Both stick to classics, though LOA — solemn hardcovers, acid-free pages, sewn bindings — aims to be a handed-down library: this season’s standouts include a second volume of Don DeLillo (with mid-career classics “Mao II” and “Underworld”) and an eye-popping revival of feminist and LGBTQ sci-fi writer Joanna Russ. Folio, no less quality-minded, is rangier, giving new illustrations to previously unillustrated work, then pairing fresh essays and slipcases. Its gorgeous new edition of Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” has an introduction by Russell Banks. Folio’s even better if you’re thinking keepsakes for children: Their latest three-volume set of the works of Roald Dahl includes the original Quentin Blake illustrations between screen-printed fabric covers, and it’s hard to imagine a more definitive “The Night Before Christmas,” pure whimsy with new childlike illustrations by Ella Beech.

“Cunk on Everything” — a spinoff of Netflix’s “Cunk on Earth,” in which Philomena Cunk (British comic Diane Morgan) plays the dimmest of historians — is a selective encyclopedia of vaguely-true knowledge, from insects (“punctuation with legs”) to xylophones (“makes sort of the same noise as a crap piano”). The toilet read of the year. “Dumb Ideas” is the backstage stories of that transgressive prank epic “The Eric Andre Show.” Andre and Dan Curry, the show’s head writer, include pranking tips, thoughts on pranking as a genre, an official-looking liability waver, even scripted pranks that (it’s hard to imagine) were too extreme for their show.

“The New Brownies’ Book” — inspired by W.E.B. Du Bois’ Brownies’ Book magazine for Black children (“Designed for all children, but especially for ours,” read its monthly inscription) — updates the original with luminous care, mixing writers of the ‘20s version (particularly Langston Hughes) with contemporary poems, art and histories. “50 Years of Ms.: The Best of the Pathfinding Magazine That Ignited a Revolution” is a decade-by-decade compendium of articles, images and readers’ letters that often read more presciently than like time capsules: Barbara Ehrenreich, Angela Davis and Alice Walker are a few of the writers included, and some of the topics are abortion, authenticity, Nancy Pelosi, Beyoncé and pronouns.

I always loved the publisher Phaidon’s direct approach to art history, and “Latin American Artists: From 1785 to Now” is exhibit A, a gargantuan, brightly designed who’s-who full of huge art images and short, approachable biographies. A gateway to worlds. Same for “Art is Art: Collaborating with Neurodiverse Artists at Creativity Explored,” though with a narrower scope: Here is a dream gallery show of artists who worked with a San Francisco nonprofit, eschewing in many cases the traditional training and “important” subjects for Pettibon-esque Red Hot Chili Peppers portraits and MCA-vibrant sculpted Frankenstein busts. A lot of it wouldn’t be out of place in “Andy Warhol: Seven Illustrated Books 1952-1959,” which often suggests Warhol might have excelled as a children’s book illustrator. Reproduced by Taschen in a large, portfolio-like size are the calling-card books he created for friends and clients: faux cookbooks, shoe catalogs, adult alphabet books.

“America’s Collection: The Art and Architecture of the Diplomatic Reception Rooms at the U.S. Department of State” is a wordy title for staid Americana, by design. Its question is: When your job is welcoming the world to your house, how do you greet them? The answer, illustrated in a mix of photographs and history, is: tasteful china, furniture by enslaved woodworkers and veritable mini-history of American landscape painting. “The Upside-Down World: Meetings with the Dutch Masters,” by Pulitzer-winning Susan Sontag biographer Benjamin Moser, is, at a glance, a gracefully illustrated art history — and perhaps a brooding snooze? What you get is coming-of-age memoir, triptych and the most charmingly casual of art educations.

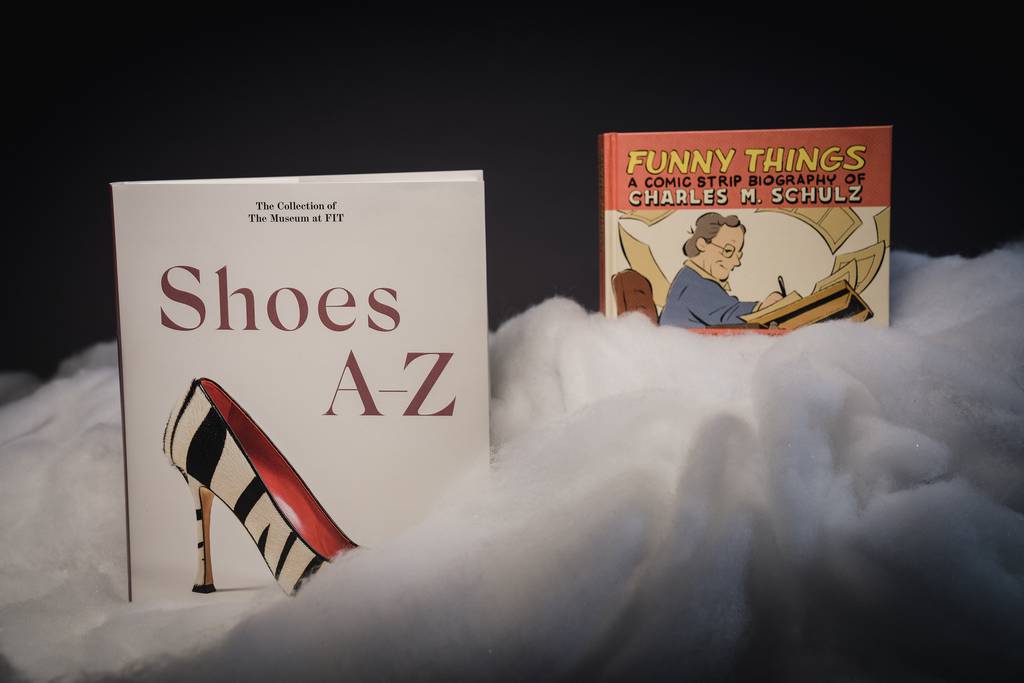

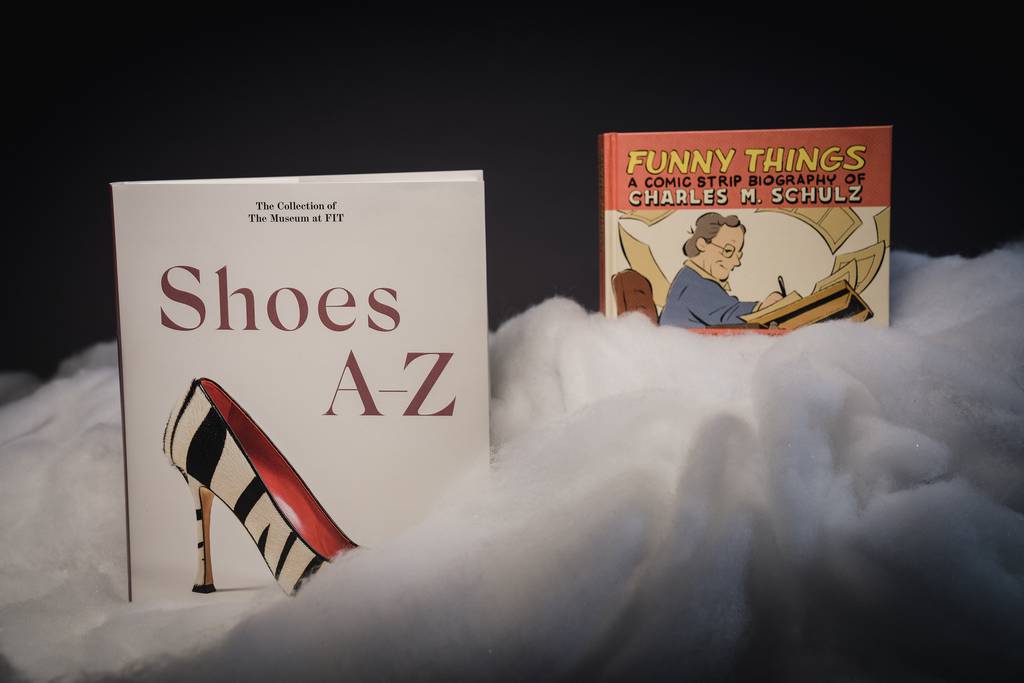

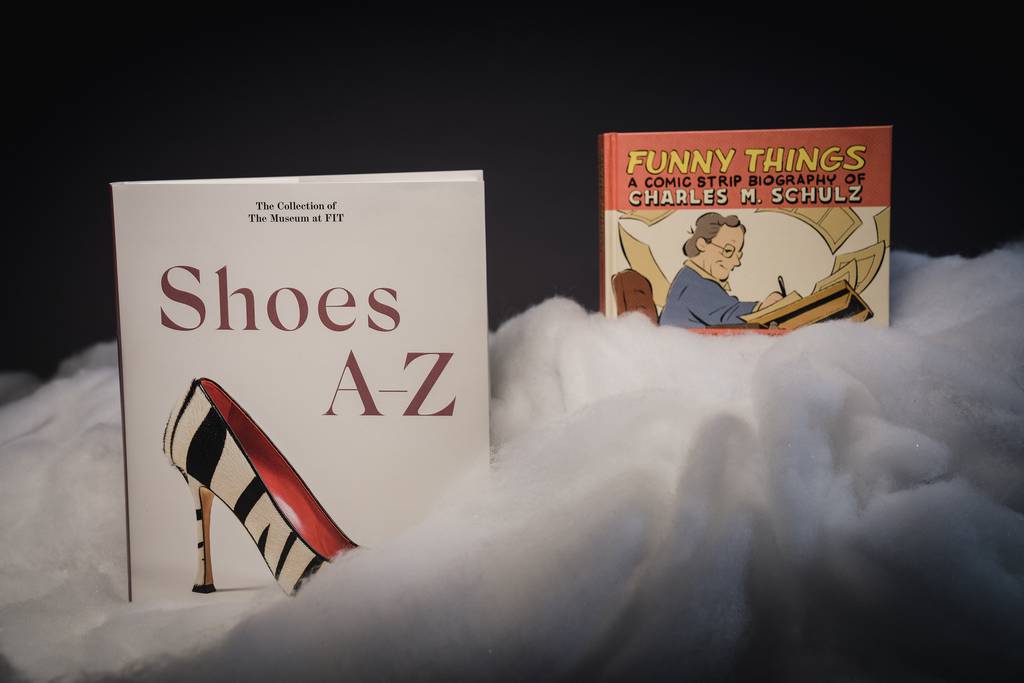

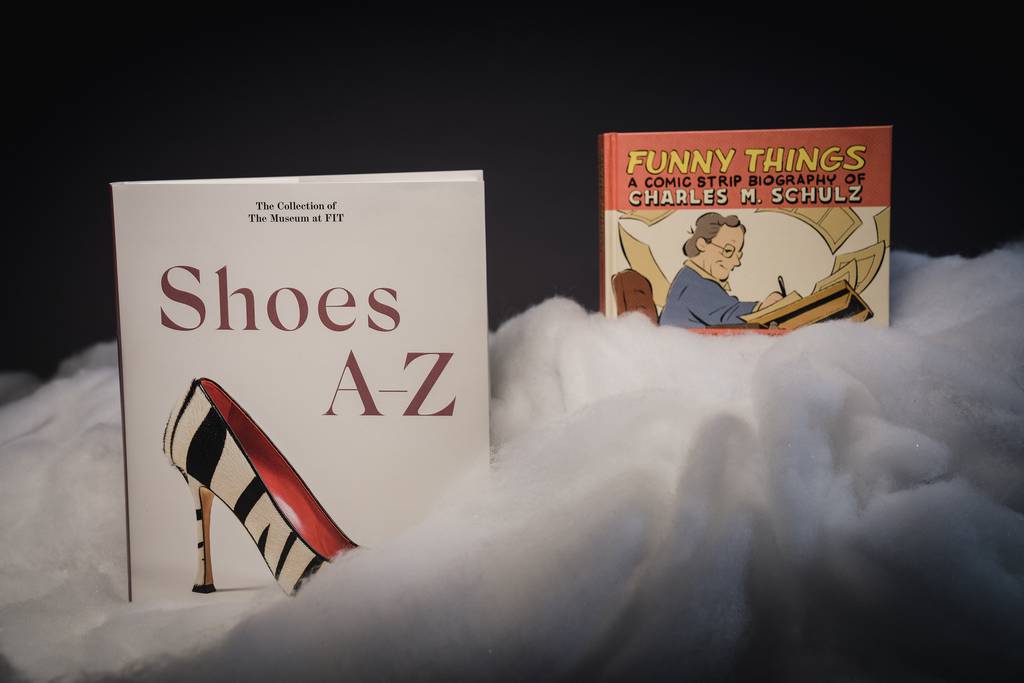

A good micro-history is a universe. For instance, I couldn’t care less about shoes, yet Taschen’s massive “Shoes A-Z,” weighing nearly 10 pounds, culled from archives at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, pairing histories with foot-tall images of both 18th century and insane contemporary ideas, is hard to stop browsing. Less niche: “The Computer: A History From the 17th Century to Today,” a mere 8 pounds, is an addicting illustrated history of the first “thinking” machines, to our all-digital now. Maps of Silicon Valley, early Super Mario design, thumbnail biographies of pioneers, a photo of the first “bug” (an actual moth). It’s a museum exhibit of sorts, held between covers. “The Object at Hand,” however — which is so compellingly told it deserved flashier, larger treatment, and in color — are the histories of 86 objects, pulled from every Smithsonian institution, a few predictable (Lincoln’s top hat, the Apollo command module), many illustrative of the vastness of the collection — Steve Aoki’s turntable, the carcass of a giant squid.

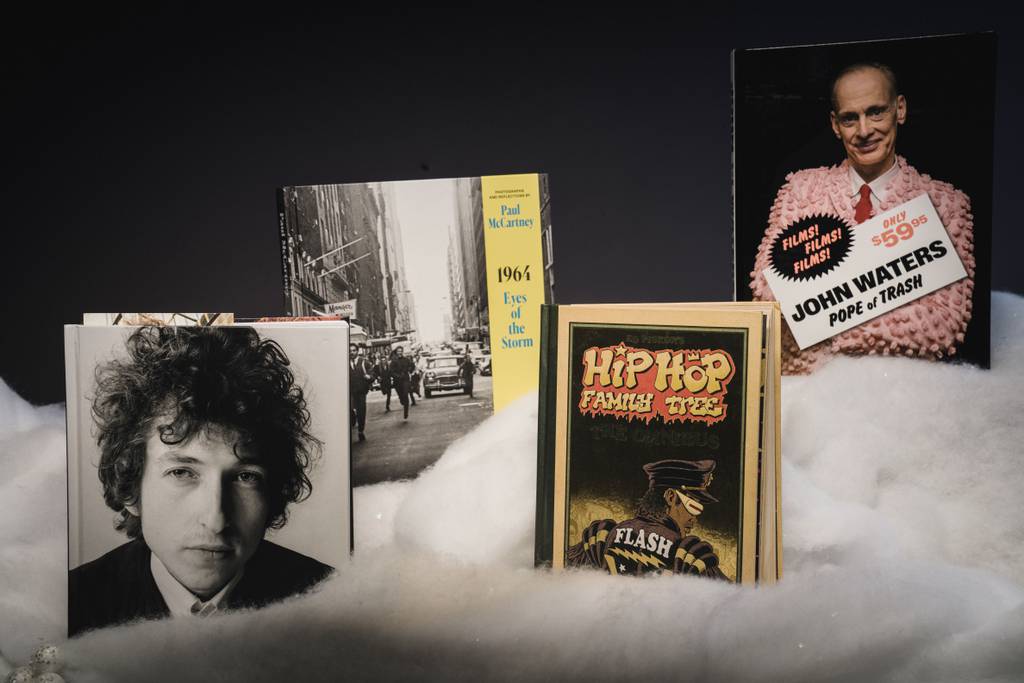

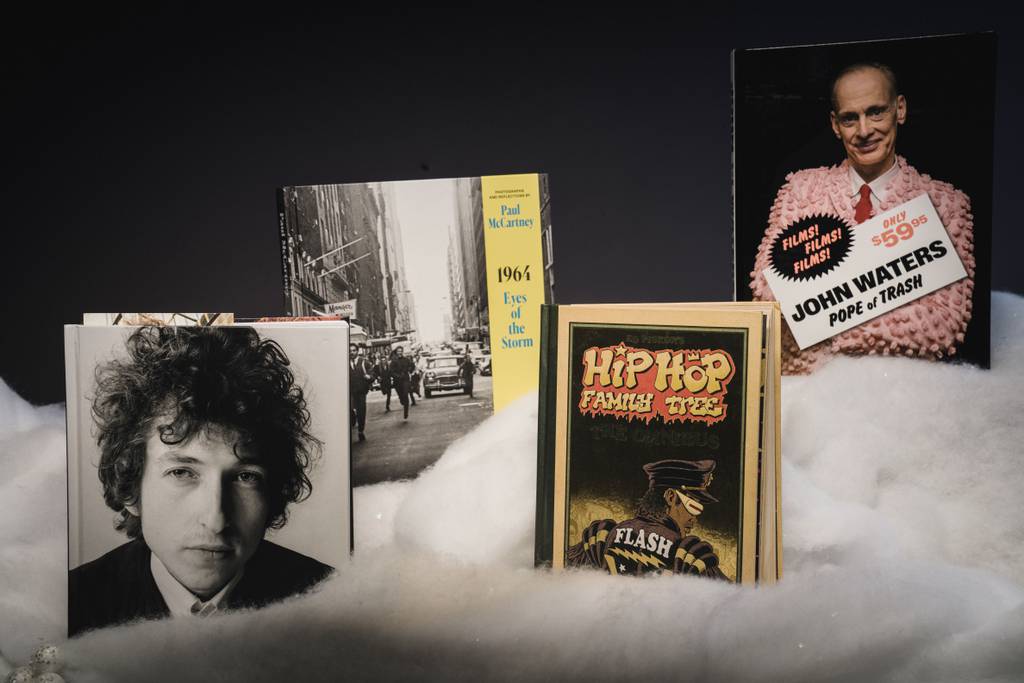

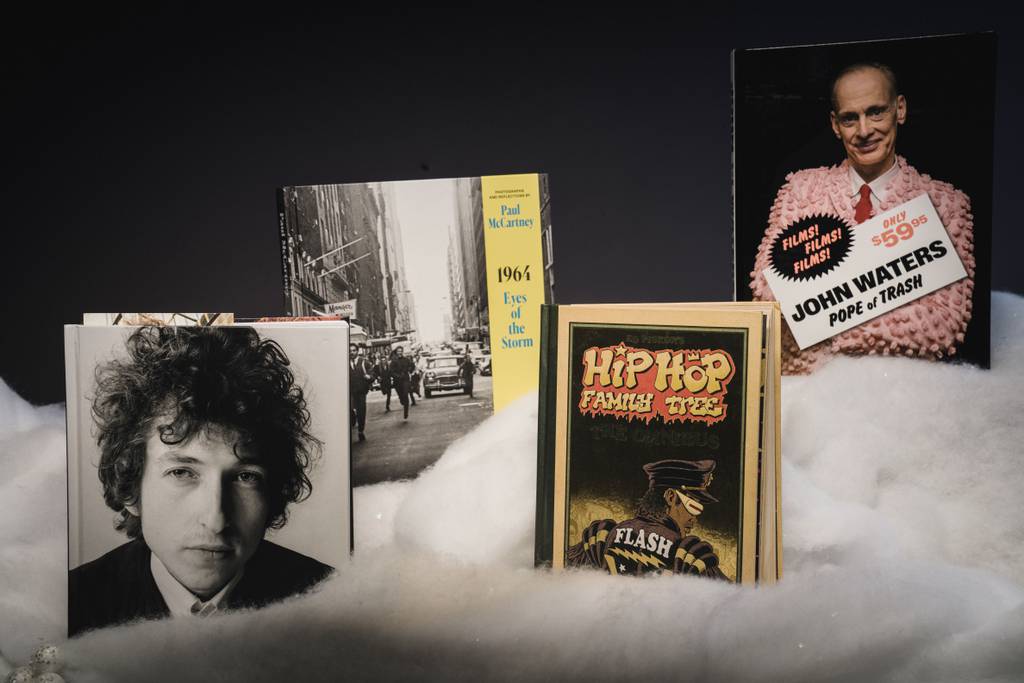

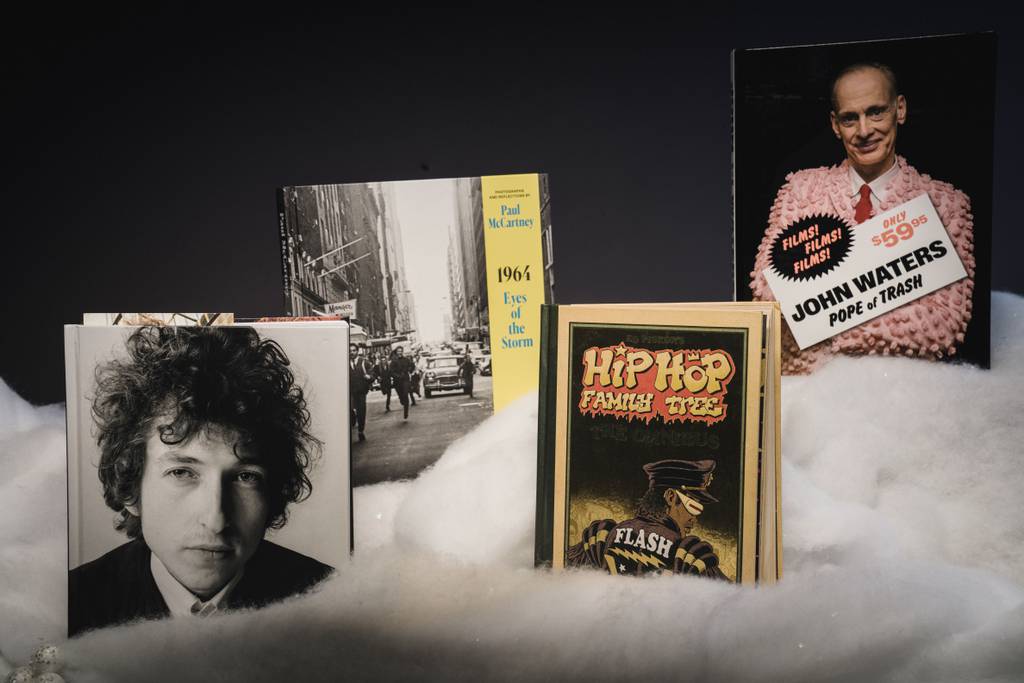

“Charles M. Schulz: The Art and Life of the Peanuts Creator in 100 Objects” is a dull title for a clever take on a museum catalog — namely, the 20-year old Schulz museum outside San Francisco. Part biography, part archive dig, personal possessions (his World War II sketch book, his ice skates) are shown alongside letters to fans and plenty of comics, including his failed attempt to draw adults. Whenever I have told anyone the new Bob Dylan Center is in Tulsa, they ask: Why Oklahoma? Because he liked the Woody Guthrie Center there so much he sold his archives to its curators. “Bob Dylan: Mixing Up the Medicine” is a 600-page argument that he made a wise choice. The format is fun: Thirty writers (a clever bunch, from Joy Harjo to Richard Hell) pick an object from the museum to write on, and the result is generous and handsomely designed — and as obsessive as you’d expect.

“Is There God After Prince?” — great title, that — is Chicago writer Peter Coviello’s cultural thoughts centered around a sharp theme: If we’re headed for collapse, what does it mean to love anything deeply? Particularly the seemingly ephemeral, like Chance the Rapper or “The Sopranos.” It’s an anxious, heady collection. “A Memoir of My Former Self,” by late-great historical novelist Hilary Mantel, billed as her final book, offers no such umbrella to its essay collection, only life itself. Some topics (Marie Antoinette, British royals) are in her wheelhouse, but others (“RoboCop,” perfume) are a showcase of the curiosity of a writer very much of her time.

“The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century” is the catalog of a recent Baltimore Museum of Art exhibition that needed more love. Using images of sculpture, photos, textiles and more — paired with crash courses on hip hop politics, club-going, Indigenous storytelling (and way more) — you get a vast, pan-discipline history, not even big enough to contain itself. Tighter, if no less varied, is “Do Remember! The Golden Era of NYC Hip-Hop Mixtapes,” a mash of playlists, cover art and interviews so fanatical, there are pages just showing record store and DJ business cards. It’s also a great example that no subject is too niche if the energy’s there. Speaking of love letters: Ed Piskor’s long-running documentary comic book “Hip Hop Family Tree” finally got its omnibus, a history stretching from the house parties of 1973 to the peak of Run DMC. If you love hip hop and comic books, it’s a no-brainer.

“Overlooked: A Celebration of Remarkable, Underappreciated People Who Broke the Rules and Changed the World,” a necessary collection of obituaries (newly written, for The New York Times’ “Overlooked” series) that, in most cases, were decades late. Specifically, “the women, the people of color, and the LGBTQ and disabled communities who made history” but never got a Times obit. It’s an unexpected blast: An engineer who saved Apollo 13, the doctor who discovered cystic fibrosis, Chicago street artist Lee Godie but also, no joke, Ida B. Wells, Robert Johnson, Sylvia Plath. “The Geography of Hate: The Great Migration Through Small-Town America,” by Purdue University’s Jennifer Sdunzik, is brief yet weighty, ripening the often-told story of the Great Migration by venturing away from Chicago and big northern cities for the small Indiana villages where many Black Americans attempted to settle in.

Paul McCartney’s “1964: Eyes of the Storm” — yes, that Paul McCartney, with an essay by Jill Lepore — is a remarkable document, yet “barely covering what followed” that breakthrough Beatles year. Here are the snapshots he took during the wild ride, of fans taking his pictures, snow shovelers, welcoming committees, rehearsals — it’s like street photography from someone who couldn’t walk down the street. “Estrus: Shovelin’ The (expletive) Since ‘87″ is the illustrated history of the proudly trashy record label that was less interesting for the acts it produced — the Soledad Brothers and Man or Astro-Man might be the standouts — than its loving mash of midcentury bargain-bin flotsam (”The Munsters,” surf rock) for posters and record covers.

“Bird Day: A Story of 24 Hours and 24 Avian Lives” is a lovely little book that travels the world, assigning a short taxonomy of a bird to each hour. Penguins at 2 p.m., nightingales at 4 a.m. A casual introduction for a wannabe birder. “The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard Year,” by NYT op-ed writer Margaret Renkl, divided into 52 chapters, paired with seasonal collages by the author’s brother, is a domestic spelunking that recalls the environmental lyricism of Annie Dillard. Renkl charts the life and death of plants and animals just past her windowpanes. By literally watching the grass grow, she offers reasons to peer closer into your own world.

It doesn’t explicitly advocate for film as a medium, but Vanity Fair’s muted, compulsive collection of “Oscar Night Sessions” nails the intimacy that a movie star somehow relates. Its photos, by Mark Seliger, make a strong argument that Hollywood hasn’t lost its glamour, only changed its faces. You don’t buy that? “Cinema of the 70s” is a straight-ahead year-by-year stroll through the milestones of Hollywood’s last golden age, starting at “Five Easy Pieces,” ending at “The Tin Drum.” A bit of backstage here, a bit of history there. Strictly celebratory. Been to the new Academy museum in Los Angeles? Me neither. But I hear it’s great, and “John Waters: Pope of Trash” is a rowdy, thoughtful catalog for one of its first shows. Also, a loving filmography, a minor class in underground cinema, a cast yearbook, a lionizing and some great contextual essays (including one by David Simon).

Chances are you’ve never heard of Ronald L. Fair’s forgotten classic “Many Thousands Gone,” just reissued by Library of America. A Chicago writer who quit in the ‘70s to be a sculptor in Finland, Fair tells the alternative history of a nook of Mississippi where slavery never ended; he reads now like a precursor to the fables of Percival Everett. Similarly, Lore Segal, a longtime New Yorker writer, at 95, should be better known: “Ladies’ Lunch” draws on 16 recent, brief, sweetly caustic slices of an aging life, full of martinis and eldercare tales. John Edgar Wideman’s “The Homewood Trilogy” — newly gathering a set of Pittsburgh novels that began in 1985 — may be an even better example of a great writer with consistently great reviews who looks fated to stay a writer’s writer. Which is why it’s nice to see 81-year old Australian writer Helen Garner — whose work transcends crime, yet often reads proudly rooted to it — given a push in this country. Start with the gripping true-crime “This House of Grief,” then try “The Children’s Bach,” about a splintering family. Just don’t expect easy conclusions.

Here’s a cool little publishing trend: biographies of cartoonists, as cartoons. Each of these new ones brings its own strength. “Three Rocks: The Story of Ernie Bushmiller, the Man Who Created Nancy,” the best of the bunch, by Bill “Zippy the Pinhead” Griffith, is art history and a moving bit of journalism about an illustrator rarely given his due. “Funny Things: A Comic Strip Biography of Charles M. Schulz” sticks dutifully to the horizontal strip format of Sunday newspapers, walking from childhood to death, replicating the ennui of “Peanuts,” without once in 400 pages offering a Snoopy or Charlie Brown. Copyright looms — as it does for different reasons in “I Am Stan: A Graphic Biography of the Legendary Stan Lee,” Tom Scioli’s evenhanded, subtly critical portrait of a man both given too much credit for being the architect of the Marvel Universe, and, at times, maybe not enough. Follow it with: “The Super Hero’s Journey,” by Patrick McDonnell of the daily comic “Mutts,” who uses early Marvel history to draw an unabashedly loving ode to Lee’s company, alternating the classroom doodles of childhood with full pages of original Marvel art.

Did you know there is an old tradition of telling ghost stories on Christmas Eve? For the past several years Canadian publisher Biblioasis has revived the tradition, one thin, tiny book at a time (illustrated by minimalistic, idiosyncratic cartoonist Seth). They’ve revived ghosts by Edith Wharton, Charles Dickens and others. The newest installment of “A Ghost Story for Christmas” ($8 a scare) includes “The Captain of the Polestar,” a polar fright by Arthur Conan Doyle.

What is, after all, “A Christmas Carol” but a ghost story, handed down, every holiday?

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.