When the photographer Gösta Peterson shot a relatively unknown model named Naomi Sims for the cover of the Fashions of the Times (a special section of The New York Times Magazine) in the summer of 1967, it heralded a seminal moment in fashion history. That arresting portrait of Sims, elegantly clad in a black cape and wide-brimmed hat, is considered the first cover by a major American fashion magazine with a mixed-race audience to feature a Black model.

“She just felt like the right model at the right time for that. We weren’t trying to prove anything,” recalls Patricia Peterson, the magazine’s editor at that time (and Gösta Peterson’s wife, with whom he frequently collaborated). Indeed, Gösta, who was known for his quick, often improvisational style of photography, was more incentivized by the allure of a fresh face than making history or notions of celebrity. Earlier that year, he was also the first of his industry peers to photograph Twiggy in the United States. Again, it was a matter of capturing images of the waifish Brit before becoming disinterested by her inevitable ubiquity.

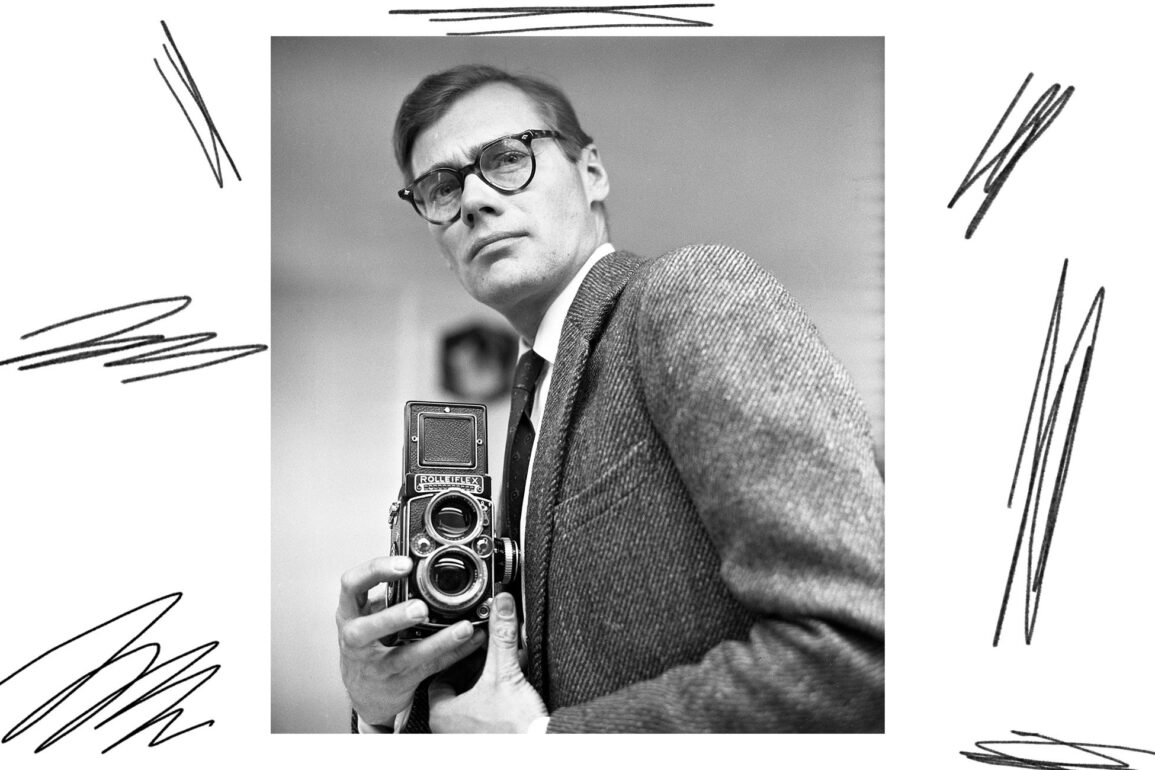

It’s hardly an overstatement to call Gösta Peterson one of the most influential, yet little-known, fashion photographers of his time. Despite his barrier-breaking work, Peterson, a self-taught lensman with a fondness for jazz and natty tweed suits from Savile Row, has remained a lesser-known figure in the pantheon of great fashion photographers from that era: Richard Avedon and Irving Penn, for example. Many of his contemporaries, including the photographer Arthur Elgort and the fashion stylist and entrepreneur Linda Rodin, both of whom worked as his assistants, attribute this astonishing omission to Peterson’s unyielding resistance toward household-name models—the Lauren Huttons and the Cheryl Tiegses of the modeling world. “It was the time of Avedon and Hiro, but Gus didn’t buy into that. He didn’t shoot Vogue because he didn’t want to work with their models,” says Rodin, whose own visual memoir, forthcoming in early 2024, will feature a sizable selection of Peterson’s photographs.

While it may have precluded him from the pages of what many industry insiders consider “the Fashion Bible” (Vogue was known for typically insisting on using its own selection of models), Peterson, who passed away in 2017 at the age of 94, was resolute. “There’s nothing worse than an over-trained model who’s lost all sense of her body’s personality,” he said in a 1983 interview with American Photography magazine. In addition to The New York Times Magazine, Peterson shot for a number of other major publications, such as Mademoiselle, Harper’s Bazaar, Elle, GQ, and Esquire.

Now, several decades after the prime of his career, Peterson is having a quiet but significant resurgence. Earlier this year, the Manhattan-based gallery Deborah Bell Photographs presented a solo retrospective show featuring more than 35 of his images. And next month, Study magazine, a quarterly publication, will dedicate its fourth issue to Peterson and his work. “His approach was so modern, his images are still so powerful,” says Study’s founder and editor in chief, Christopher Niquet, who was first introduced to Peterson’s oeuvre by a friend, the fashion photographer Steven Meisel—a longtime admirer of the late photographer.

“He was the fashion photographer’s photographer. A lot of people on the inside really appreciated him, but on the outside, he didn’t have that much exposure,” notes Peterson’s son, Jan, who frequently assisted his father in his 87th Street studio near the family’s Upper East Side home. Peterson has had an influence on the work of other photographers, including Deborah Turbeville and Diane Arbus.

So who was Gösta Peterson, the Swedish-born illustrator turned pioneering photographer, with little interest in widespread recognition—but who was no less deserving of it? Originally an illustrator by training and trade, Peterson worked at a top advertising firm in Stockholm after serving in the Swedish military during World War II. When he accepted a relative’s invitation to the United States, his colleagues feted him farewell with a Rolleiflex camera, a fortuitous offering if any. Peterson arrived in New York in 1948, and—as many recall his own telling—he went straight to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, then Harlem, where the city’s buzzing locus of jazz clubs would provide unceasing entertainment and amusement in the years that followed.

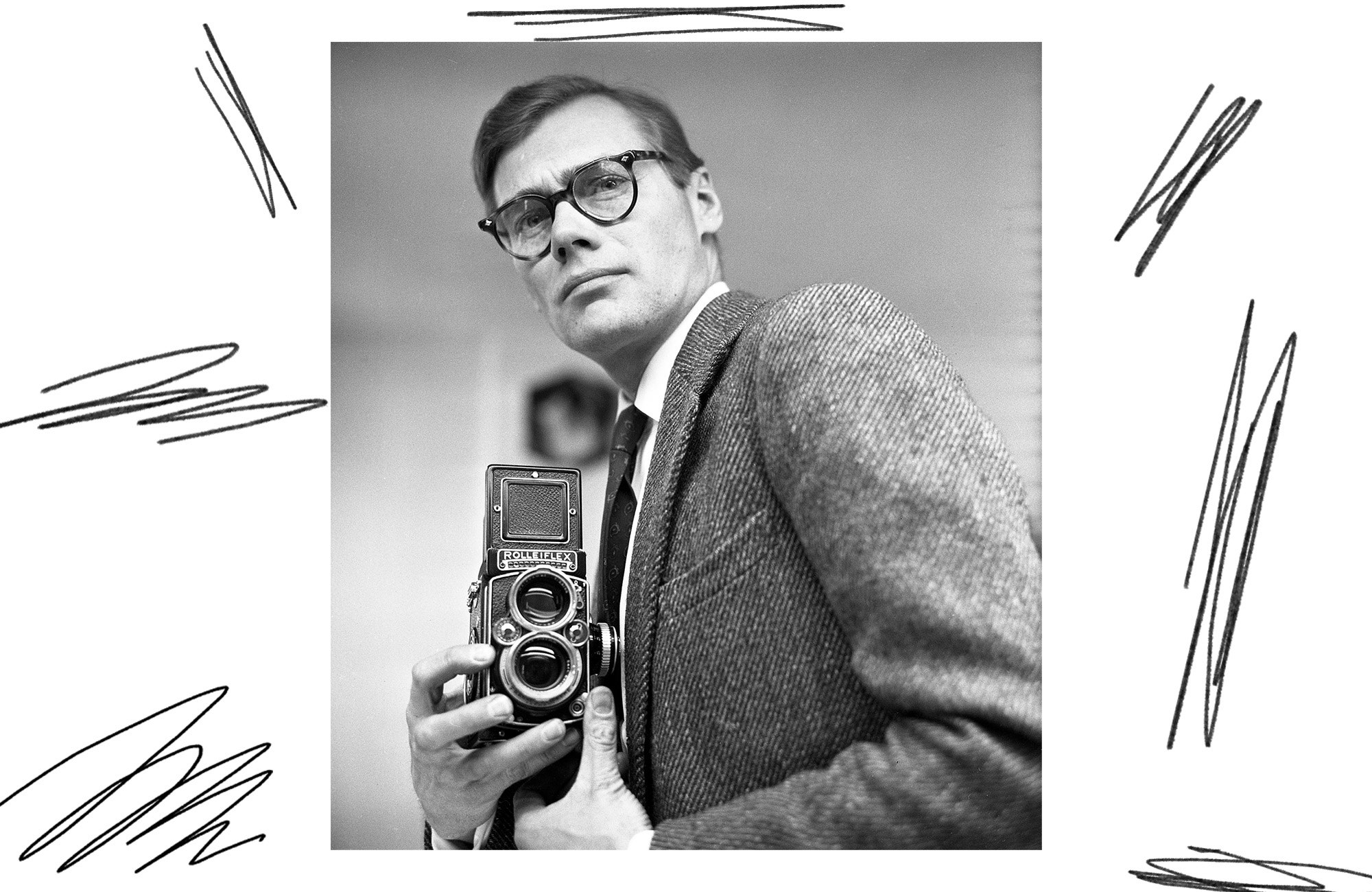

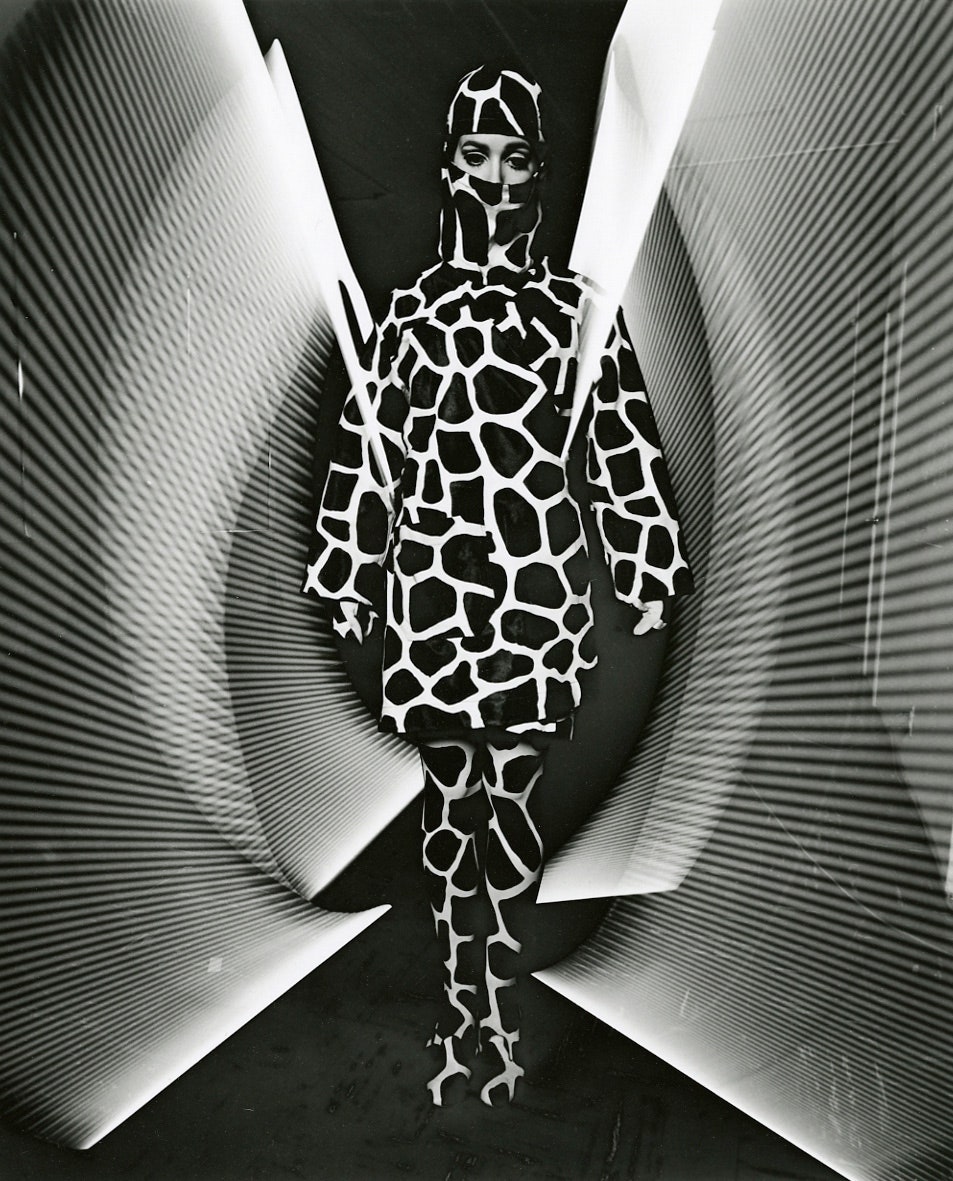

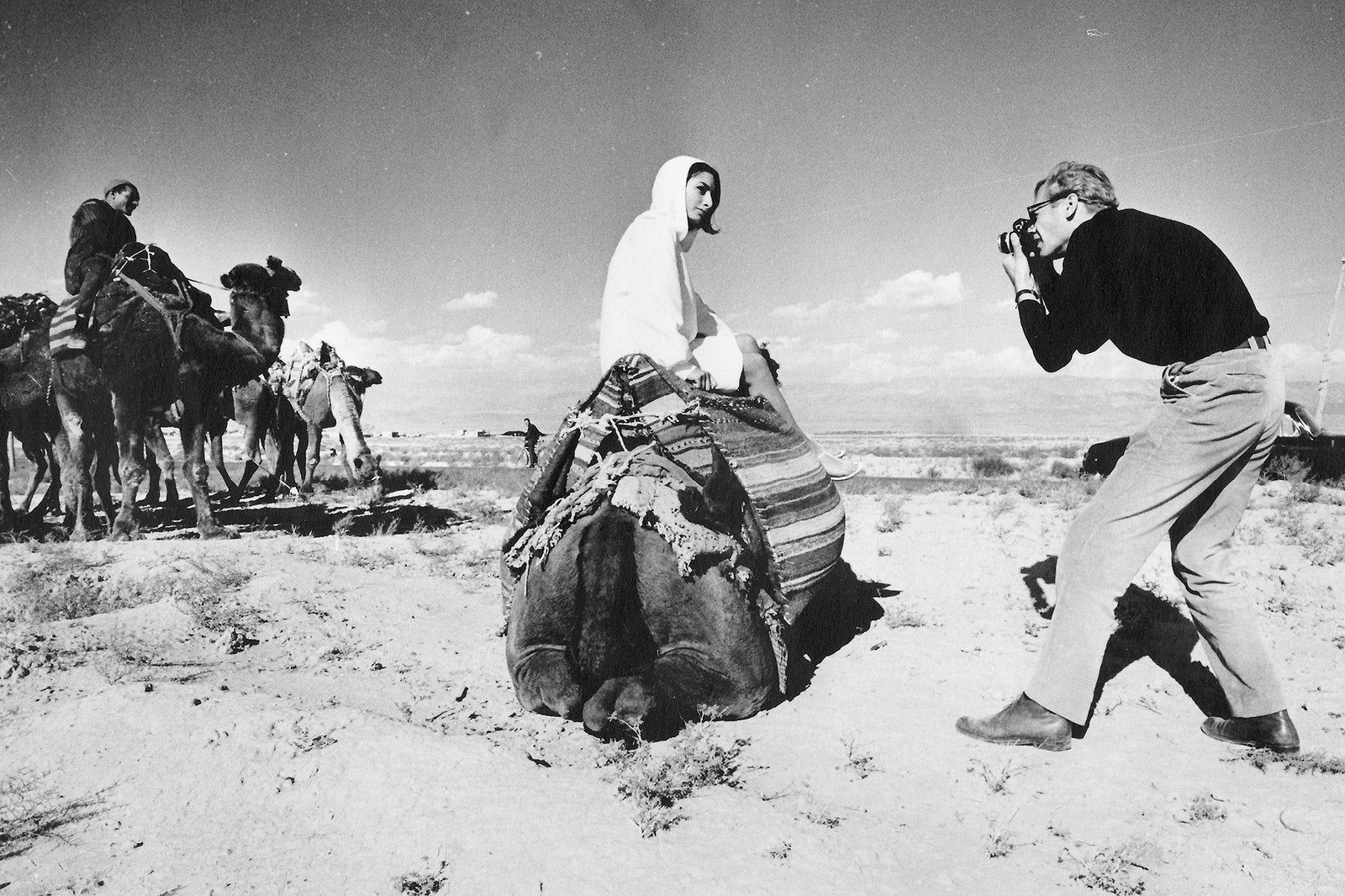

Whether or not the freeform expressions of jazz directly informed his own self-taught approach to photography, Peterson’s improvisational, often spontaneous, shot-on-the-street style became his trademark as he picked up a growing succession of freelance jobs from magazines. The assignments increased in scope and prestige, and yet the inherent, snapshot-like energy of his images typically endured. “He was very quick. And funny,” recalls Arthur Elgort. Peterson’s images often featured pairings or groups of models that conveyed a sense of curious engagement, almost seeming surreptitiously documented in medias res—especially when shot from atypical angles such as looking upwards from below.

In 1975, Linda Rodin sought Peterson out for a job after discovering his photographs in a number of her favorite magazines. “They were playful and beautiful. They had a sense of humor, but also elegance to them,” she recalls. Inside the studio, Rodin witnessed Peterson’s impulsive approach firsthand: “You know, he just got it. Like, snap. He would take the one shot, and that was it. Nothing was labored.” That propensity for speed served Peterson well when he found himself with only about 30 minutes to shoot Twiggy for The New York Times Magazine—as did his lack of cumbersome equipment. Often, he wore a multipocketed safari jacket from Abercrombie & Fitch to keep his light meter and extra rolls of film within reach.

“He used to laugh when people said, ‘Oh, you’ve got to get the new Nikon. It’s got the greatest lens and it takes the best pictures.’ And he’d say, ‘Hold on, everybody. No camera takes the best pictures. It’s the person holding the camera who takes the best pictures. It’s their eye, it’s not the equipment,’” recounts Rodin. If anything, it was the alchemy of photographer and model—not elaborate sets, nor flashy technical equipment—that made Peterson’s photographs so one of a kind: provocative, curious, memorable images born from his ability to convey an abundance with remarkably little.

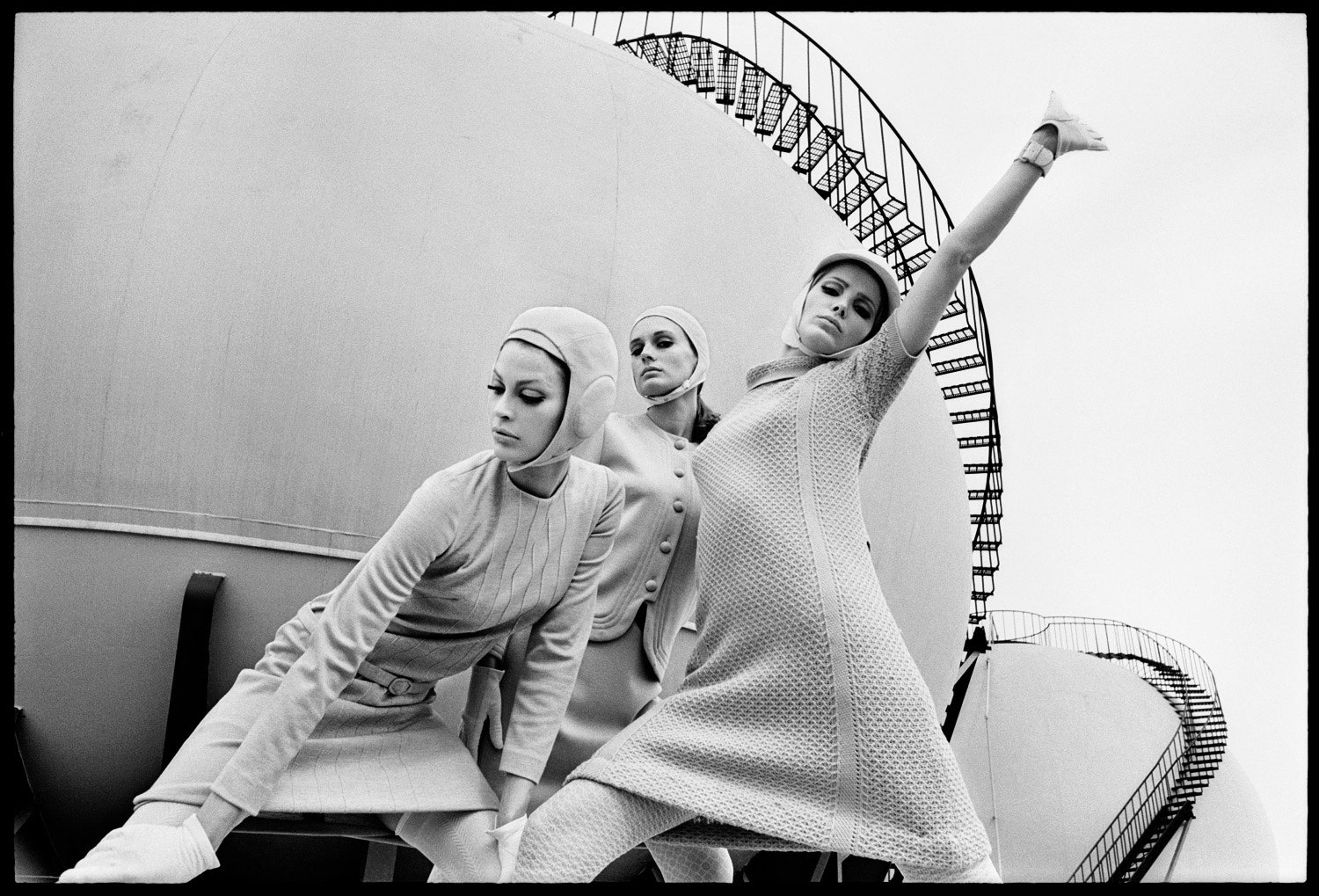

Jan Peterson, who oversees his father’s archives along with his sister, Annika, notes the integral character of Peterson’s models. “He generally picked models that were kind of peculiar or quirky or funny-looking in some way. Or he’d pick very strong women, and usually use them in the more graphic pictures, which helped embody the whole statement,” he explains. A black-and-white photo from a 1967 issue of Harper’s Bazaar features three models clustered together, crouched and contorted to mirror the curvilinearity of a staircase in the background, for example. Sure, it was a fashion spread meant to showcase the clothes, but Peterson’s photos often expressed a fuller idea that absorbed the fashion into the entirety of the composition.

When it debuts next month, Study’s latest volume will feature a mostly pictorial gallery of Peterson’s photographs, alongside a text by the French author Avril Bénard. For founder Christopher Niquet, who hopes the forthcoming tribute might impel a published book of the photographer’s images sometime in the near future, the enduring quintessence of Gösta Peterson’s work lies in its anachronistic representation of the past in the current present. “You never feel like you’re looking at a ’60s model in a ’60s dress, photographed with ’60s tricks,” Niquet says. “They are timeless.”

More Great Stories From Vanity Fair

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.