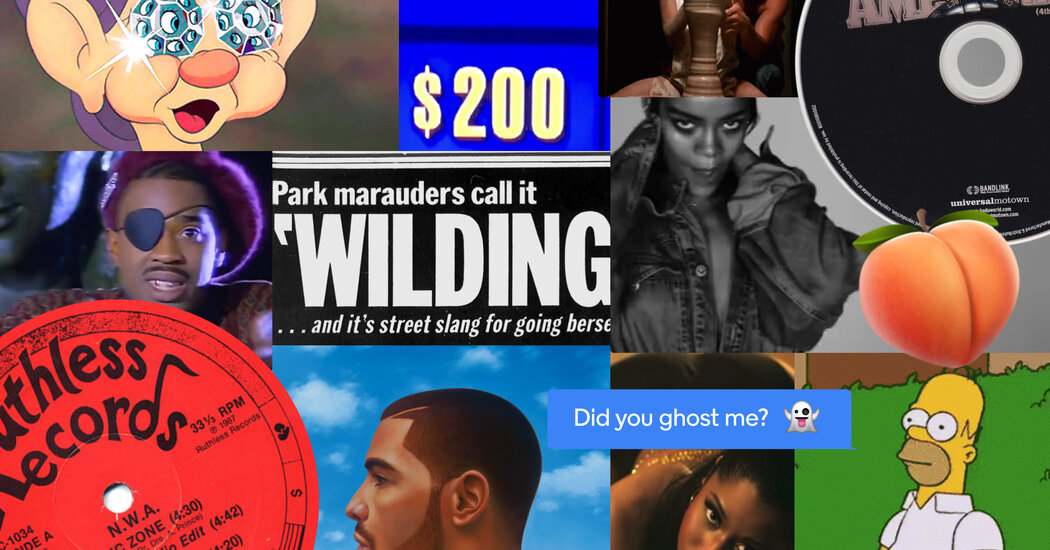

In 50 years, rap transformed the English language, bringing the Black vernacular’s vibrancy to the world.

“Dave, the dope fiend shootin’ dope.” — Slick Rick, “Children’s Story” (1988)

“Dopeman, dopeman!” — N.W.A, “Dope Man” (1987)

Homer Simpson

going ghost.

We unpacked five words — dope, woke, cake, wildin’ and ghost — that demonstrate rap’s unique linguistic influence.

“Four, five seconds from wildin’” — Rihanna, “FourFiveSeconds” (2015)

The Daily News reported on wilding in April 1989.

“I stay woke” — Erykah Badu, “Master Teacher” (2008)

In 2017, woke made a wry breakthrough as a “Jeopardy!” category.

“I got cake and I know he want a slice” — Megan Thee Stallion, “Sweetest Pie” (2022)

The component “start” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

dope

[doʊp] noun. A recreational drug; adj. Very good.

One emblematic use of linguistic transformation in hip-hop is the total inversion of a word’s meaning. Consider “dope,” which apparently originated in the 19th century from the Dutch doop, which means “dipping sauce.” In 1909, “dope” was employed to describe the “thick treacle-like preparation used in opium smoking,” per the Oxford English Dictionary. But “dope” also had another meaning: a stupid person. In the wider culture, stereotypes of Black people as being unintelligent still endured, so it was an act of radical reclamation when, in the 1980s, rappers began to use “dope” to refer to superlative music, lyrics, fashion or anything else considered praiseworthy.

Supposedly the first known use in hip-hop: “You better look alive, not like you take dope” — Spoonie Gee, “Spoonin Rap” (1979).

“You gon’ be a dope fiend, your friends should call you Dopey” — Lil Wayne, “Every Girl” (2009)

“Just give me one more sniffle/Another sniffle of that dope” — Victoria Spivey’s “Dope Head Blues” (1927)

Hip-hop made “dope” — and also the genre at large — the arbiter of cool. And unlike similar inversions like “sick” or “bomb,” its pop-cultural usage as a synonym for “outstanding” persists into the present day.

“It’s just two dope boys in a Cadillac” — OutKast, “Two Dope Boyz (In a Cadillac)” (1996)

“Dope” (executive produced by Pharrell Williams) crafted a coming-of-age dramatic comedy for Generation Z, starring Shameik Moore, the rapper A$AP Rocky and Zoë Kravitz.

“Yo, I’m crazy dope, with super hype lines/And a lot of hype lines make one dope rhyme” — LL Cool J, “Why Do You Think They Call It Dope?” (1989)

The component “end” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

“Dope” is such a part of the American lexicon that it has been written into dialogue in popular TV shows: HBO’s “2 Dope Queens” and NBC’s “The Good Place” and “Friends.”

“Be young, be dope, be proud/Like an American” — Lana Del Rey, “American” (2012). The music video references the American adventure comedy film “Joe Dirt.”

The component “start” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

woke

[‘wok] adj. The state of being aware or conscious.

It started as the simple past tense of the word “wake,” meaning the state of being awake, partly from the Middle English wakien. The Pan-Africanist activist Marcus Garvey used aphorisms like “Wake up, Ethiopia! Wake up, Africa!” back in the early 1920s. Eighty years later, on her “MTV Unplugged No. 2.0” album, Lauryn Hill would go on to repeat the same sentiment: “Wake up and rebel/We must destroy in order to rebuild.” The modern sociopolitical application of “woke” was repopularized by the Black Lives Matter movement and the reprise of both protest music and conscious rap that followed in the early 2010s.

The Black nationalist Marcus Garvey intoned “Wake up, Africa!” in the 1920s.

The blues singer Ramblin’ Thomas sang “stay woke” on “Sawmill Moan” (1928).

The novelist William Melvin Kelley’s 1962 New York Times essay presciently explored the appropriation of intra-cultural Black language.

Erykah Badu’s 2008 song “Master Teacher” repopularized “woke” within hip-hop culture. Badu recently said that the word “doesn’t belong to us anymore.” But months later, she went on to say: “Woke can never be dead. … No matter what people say it is, it is a state of being.”

The component “end” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

“But stay woke/Niggas creepin’/They gon’ find you/Gon’ catch you sleepin’” — Childish Gambino, “Redbone” (2016)

The component “start” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

The use of the word “woke” in hip-hop lyrics surged once again after the 2016 presidential election of Donald J. Trump: including Kendrick Lamar’s “N95” (“Take off the fake woke”), Joey Bada$$’s “Good Morning Amerikkka” (“Some of us woke while some stay snoozed”), Lil Durk’s “Home Body” (“Stay woke, you can’t take it”), 6LACK’s “Nonchalant” (“Claim they woke but they probably asleep”) and many others. But “woke” soon became a source of derision, as evidenced by comments from the Republican presidential candidate Ron DeSantis and the billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk. It remains to be seen whether mockery of the word will cause its use to decline, or whether rap will find ingenious ways to reclaim it.

Black nationalism seeped into the mainstream when Hulu debuted its comedy series “Woke” in 2020.

The rise of “woke” coincided with the rising social awareness of activist movements like Black Voters Matter.

In 2022, Elon Musk posted a tweet mocking a trove of #StayWoke T-shirts he discovered.

The component “end” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

The component “start” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

cake

[keɪk] noun. An item of sweet food, baked and often decorated.

Hip-hop has always celebrated booties and invented various euphemisms to refer to them. But this has typically been from the point of view of a male rapper’s sexual fantasies (Sir Mix-a-Lot basically made a career of this). Part of what’s notable about the abundant references to “cake” in hip-hop lyrics of the last decade is how often female rappers are the ones behind the mic. As the culture has adopted a sexual politic that centers female pleasure, and women have become a bigger force in the genre, they have not only taken ownership of their sexuality; they’ve taken back raunch.

“I got cake and I know he want a slice” — Megan Thee Stallion, “Sweetest Pie” (2022)

Megan Thee Stallion flaunts her body-ody-ody-ody-ody on “Saturday Night Live.”

Songs like Cardi B’s “WAP,” Ice Spice’s “Munch (Feelin’ U)” and Sexyy Red’s “Pound Town” represent female rappers reclaiming raunch.

In “Girls in the Hood,” Megan Thee Stallion raps, “He call me Patty Cake ’cause the way that ass shake.” Women’s erotic imagination is at the fore in these songs, not men’s, as in “Trollz,” in which Nicki Minaj boasts, “Just put it in his face, all this cake, he wanted a taste.” (Or Rihanna’s simply rapping, “Cake, cake, cake, cake, cake.”) Another variant of this usage is “caked up,” meaning having well-developed gluteal muscles.

“Heard in three weeks, she sniffed a whole half a cake up” — Notorious B.I.G., “Ten Crack Commandments” (1997)

Jay-Z released “Big Pimpin” in 2000, the same year as Sisqó’s “Thong Song.” A bootyful coincidence?

“Cake” is also used to refer to copious amounts of money or cocaine. E.g., “Stackin’ the cake makes rainy days sunny” — Shaq, “Legal Money” (1996)

The actor Al Pacino as the drug lord Tony Montana in the 1983 film “Scarface,” with mounds of cocaine.

The component “end” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

The component “start” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

“Cake, cake-cake, cake-cake, cake/500 million, I got a pound cake” — Jay-Z on Drake’s “Pound Cake/Paris Morton Music 2” (2013)

The component “end” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

The component “start” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

wildin’

[waɪldɪŋ] adj. Not cultivated or domesticated; noun. Wild or mischievous behavior.

Early definitions of this word, dating back to about 1525, referred to plants growing uncultivated in the wild. In hip-hop’s lexicon, a “wildstyle” referred to an intricate form of graffiti, and in the mid-1980s, “wildin’” became one of many ways to describe someone acting in an uninhibited or reckless manner. Musical evidence of wildin’ surfaces as early as 1988 in Ice-T’s “Radio Suckers” (“Gangs illin’, wildin’ and killin’/Hustlers on a roll, like they got a million”). Sometimes it took a different spelling, as per the debut single from Public Enemy’s former D.J., Terminator X, “Buck Whylin’.” But uninhibited Blackness has always inspired fear in mainstream America, and so this word also came to be used against the community that created it.

The rapper Chuck D appeared in the Public Enemy D.J. Terminator X’s video for “Buck Whylin’” (1991).

“Father of all stylin’, I be wildin’ on wax” — Jeru the Damaja, “D. Original” (1994)

“Wild Style” (1982) is regarded as the first hip-hop film.

“Be my queen if you know what I mean and let us do the wild thing” — Tone Loc, “Wild Thing” (1988)

Tonya Harding skated to Tone Loc’s “Wild Thing” in the 1991 U.S. figure-skating championships, winning first place.

The component “end” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

MTV introduced Nick Cannon’s “Wild ’N Out,” an improv comedy show, in 2005.

The Daily News reported on wilding in April 1989.

The component “start” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

During the 1989 Central Park rape case, which resulted in the wrongful convictions of five Black and Latino teenagers, fear-mongering headlines used the word “wilding” to whip up white anxiety about out-of-control Black youth rampaging in the city. Senior detectives claimed that the Central Park Five suspects had used the word to describe their own actions to the police, but this account was questioned by the investigative reporter Barry Michael Cooper, who speculated that a detective may have misunderstood the suspects’ use of the phrase “doin’ the wild thing,” a lyric from the rapper Tone Loc’s 1988 single, “Wild Thing,” which they were reportedly singing while in the holding cell. In 1989, the Oxford English Dictionary added this definition: “The action or practice by a gang of youths of going on a protracted and violent rampage in a street, park or other public place, attacking or mugging people at random along the way.” Today the use of “wildin’” in hip-hop persists as a celebration of wildness, unruliness and boisterousness, a carefully calculated refusal of control. (See A$AP Rocky’s song “Wild for the Night”: “Wilding for the night, [expletive] being polite, boy.”)

Donald Trump’s infamous full-page ad calling for the death penalty for “roving bands of wild criminals” was obviously directed at the teenagers falsely accused in the 1989 Central Park rape case.

“Now I’m four, five seconds from wildin’/And we got three more days ’til Friday” — Rihanna, “FourFiveSeconds” (2015)

Wildin’ all around the world.

The component “end” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

The component “start” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

ghost

[goʊst] verb. To leave or escape suddenly and discreetly; to disappear.

The word “ghost,” used as a noun, derived from the Old English gast, meaning the disembodied spirit of a dead person, began to take on a new meaning in the 1980s: to depart from an area, or “get ghost.” One of the earliest recorded uses of “ghost” in this sense dates back to a 1991 collaboration between the hip-hop duos 3rd Bass and Nice & Smooth on the song “Microphone Techniques”: “Greg Nice, I’m outta here, ghost!” (A related term with a similar definition, “Swayze,” stemmed from the actor Patrick Swayze’s starring role in Hollywood’s 1990 romantic fantasy “Ghost.”)

“Greg Nice, I’m outta here, ghost!” — 3rd Bass and Nice & Smooth, “Microphone Techniques” (1991)

“So here’s the news, I’m ghost, I’m outta here, long gone” — Guy, featuring Heavy D, “Do Me Right” (1991)

Remember when ghosting was friendly?

A related term with a similar definition, “Swayze,” stemmed from the actor Patrick Swayze’s “Ghost.”

Notorious B.I.G. referenced the film “Ghost” on his featured verse on 2Pac’s “Runnin’ (Dying to Live)”: “When he drop, take his Glock and I’m Swayze.”

In its original appearance, “ghost” was an example of the voracious, playful curiosity at the heart of Black vernacular and hip-hop lingo. Like that lingo itself, the phrase pulled from distinct parts of American culture to make something new, eventually giving us a new way to speak about our lives. More recently, driven by social media, “ghosting” has evolved to describe the disappearance of acquaintances or love interests who cut off all communication. It’s part of the lingua franca of modern dating in the Tinder/Bumble era.

TikTok’s @jseay_ (the actor Jared Seay) doles out relationship advice on being ghosted.

Adidas released semi-see-through X Ghosted soccer cleats in 2020.

“The Office,” Season 4, Episode 10.

The component “end” is missing. Please import it manually on

src/routes/(pages)/$PAGE/+page.svelte

and add it to the body loop referencing a name on the Google Doc.

Rolls-Royce Motor Cars unveiled its newest luxury Ghost model in 2009.

Credits

Badu: Matt Jelonek/Getty Images. ‘‘Dope’’ poster: Open Road Films. Dopey: Disney. Car: Rolls-Royce. Garvey: George Rinhart/Corbis, via Getty Images. Musk: Screen grab from Twitter. Megan Thee Stallion: Matt Winkelmeyer/Getty Images and S.N.L. Newspaper clippings: Daily News. Notorious B.I.G.: Raymond Boyd/Getty Images. OutKast: Rick Diamond/WireImage/Getty Images. Seay: Screen grab from TikTok. Simpson: Fox. Spivey: Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy. Sneaker: Adidas. Stay Woke Florida: ZUMA Press, Inc./Alamy Live News, via Associated Press. Video stills: Screen grabs from YouTube. “Wild ’N Out’’ poster: MTV. “Woke” poster: Hulu.

Miles Marshall Lewis is a Harlem-based writer who spent his formative years in the Bronx, the birthplace of hip-hop culture. His most recent book, published in 2021 by St. Martin’s Press, is a cultural biography on the Pulitzer Prize-winning rapper Kendrick Lamar. Lewis lived in Paris for seven years during the 2000s, where he heard firsthand how American rap music affects speech on a global level.

Design and produced by Antonio De Luca and Sean Catangui.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.